The Evolution of Adolf Hitler's Weltanschuung

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler As the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20Th & 21St Century Literature: Vol

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 44 October 2019 Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth- First Century French Fiction Marion Duval The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Duval, Marion (2019) "Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, Article 44. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.2076 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction Abstract Adolf Hitler has remained a prominent figure in popular culture, often portrayed as either the personification of evil or as an object of comedic ridicule. Although Hitler has never belonged solely to history books, testimonials, or documentaries, he has recently received a great deal of attention in French literary fiction. This article reviews three recent French novels by established authors: La part de l’autre (The Alternate Hypothesis) by Emmanuel Schmitt, Lui (Him) by Patrick Besson and La jeunesse mélancolique et très désabusée d’Adolf Hitler (Adolf Hitler’s Depressed and Very Disillusioned Youth) by Michel Folco; all of which belong to the Twenty-First Century French literary trend of focusing on Second World War perpetrators instead of their victims. -

Adolf Hitler and the Psychiatrists

Journal of Forensic Science & Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2348-9804 Research Article Open Access Adolf Hitler and the psychiatrists: Psychiatric debate on the German Dictator’s mental state in The Lancet Robert M Kaplan* Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, Australia *Corresponding author: Robert M Kaplan, Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, Australia, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Robert M Kaplan (2017) Adolf Hitler and the psychiatrists: Psychiatric debate on the German Dictator’s mental state in The Lancet. J Forensic Sci Criminol 5(1): 101. doi: 10.15744/2348-9804.5.101 Received Date: September 23, 2016 Accepted Date: February 25, 2017 Published Date: February 27, 2017 Abstract Adolf Hitler’s sanity was questioned by many, including psychiatrists. Attempts to understand the German dictator’s mental state started with his ascension to power in 1933 and continue up to the present, providing a historiography that is far more revealing about changing trends in medicine than it is about his mental state. This paper looks at the public comments of various psychiatrists on Hitler’s mental state, commencing with his rise to power to 1933 and culminating in defeat and death in 1945. The views of the psychiatrists were based on public information, largely derived from the news and often reflected their own professional bias. The first public comment on Hitler’s mental state by a psychiatrist was by Norwegian psychiatrist Johann Scharffenberg in 1933. Carl Jung made several favourable comments about him before 1939. With the onset of war, the distinguished journal The Lancet ran a review article on Hitler’s mental state with a critical editorial alongside attributed to Aubrey Lewis. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Year 9 Grammar Stream Knowledge Organiser 2020

Year 9 – Grammar Stream Knowledge Organisers Term 3 Swindon Academy 2020-21 Name: Tutor Group: Tutor & Room: “If you are not willing to learn, no one can help you. If you are determined to learn, no one can stop you.” Using your Knowledge Organiser and Quizzable Knowledge Organiser Knowledge Organisers Quizzable Knowledge Expectations for Prep and for Organisers using your Knowledge Organisers 1. Complete all prep work set in your subject prep book. 2. Bring your prep book to every lesson and ensure that you have completed all work by the deadline. 3. Take pride in your prep book – keep it neat and tidy. 4. Present work in your prep book to the same standard you are expected to do in class. Knowledge Organisers contain the These are designed to help you quiz essential knowledge that you MUST yourself on the essential Knowledge. know in order to be successful this year 5. Ensure that your use of SPAG is accurate. and in all subsequent years. 6. Write in blue or black pen and sketch in pencil. Use them to test yourself or get They will help you learn, revise and someone else to test you, until you 7. Ensure every piece of work has a title and date. retain what you have learnt in lessons are confident you can recall the in order to move the knowledge from information from memory. your short-term memory to long- 8. Use a ruler for straight lines. term memory. 9. If you are unsure about the prep, speak to your teacher. Top Tip Don’t write on your Quizzable Knowledge Organisers! 10. -

The Mind of Adolf Hitler: a Study in the Unconscious Appeal of Contempt

[Expositions 5.2 (2011) 111-125] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747-5376 The Mind of Adolf Hitler: A Study in the Unconscious Appeal of Contempt EDWARD GREEN Manhattan School of Music How did the mind of Adolf Hitler come to be so evil? This is a question which has been asked for decades – a question which millions of people have thought had no clear answer. This has been the case equally with persons who dedicated their lives to scholarship in the field. For example, Alan Bullock, author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, and perhaps the most famous of the biographers of the Nazi leader, is cited in Ron Rosenbaum’s 1998 book, Explaining Hitler, as saying: “The more I learn about Hitler, the harder I find it to explain” (in Rosenbaum 1998, vii). In the same text, philosopher Emil Fackenheim agrees: “The closer one gets to explicability the more one realizes nothing can make Hitler explicable” (in Rosenbaum 1998, vii).1 Even an author as keenly perceptive and ethically bold as the Swiss philosopher Max Picard confesses in his 1947 book, Hitler in Ourselves, that ultimately he is faced with a mystery.2 The very premise of his book is that somehow the mind of Hitler must be like that of ourselves. But just where the kinship lies, precisely how Hitler’s unparalleled evil and the everyday workings of our own minds explain each other – in terms of a central principle – the author does not make clear. Our Deepest Debate I say carefully, as a dispassionate scholar but also as a person of Jewish heritage who certainly would not be alive today had Hitler succeeded in his plan for world conquest, that the answer Bullock, Fackenheim, and Picard were searching for can be found in the work of the great American philosopher Eli Siegel.3 First famed as a poet, Siegel is best known now for his pioneering work in the field of the philosophy of mind.4 He was the founder of Aesthetic Realism.5 In keeping with its name, this philosophy begins with a consideration of strict ontology. -

Paper 3 Weimar and Nazi Germany Revision Guide and Student Activity Book

Paper 3 Weimar and Nazi Germany Revision Guide and Student Activity Book Section 1 – Weimar Republic 1919-1929 What was Germany like before and after the First World War? Before the war After the war The Germans were a proud people. The proud German army was defeated. Their Kaiser, a virtual dictator, was celebrated for his achievements. The Kaiser had abdicated (stood down). The army was probably the finest in the world German people were surviving on turnips and bread (mixed with sawdust). They had a strong economy with prospering businesses and a well-educated, well-fed A flu epidemic was sweeping the country, killing workforce. thousands of people already weakened by rations. Germany was a superpower, being ruled by a Germany declared a republic, a new government dictatorship. based around the idea of democracy. The first leader of this republic was Ebert. His job was to lead a temporary government to create a new CONSTITUTION (SET OF RULES ON HOW TO RUN A COUNTRY) Exam Practice - Give two things you can infer from Source A about how well Germany was being governed in November 1918. (4 marks) From the papers of Jan Smuts, a South African politician who visited Germany in 1918 “… mother-land of our civilisation (Germany) lies in ruins, exhausted by the most terrible struggle in history, with its peoples broke, starving, despairing, from sheer nervous exhaustion, mechanically struggling forward along the paths of anarchy (disorder with no strong authority) and war.” Inference 1: Details in the source that back this up: Inference 2: Details in the source that back this up: On the 11th November, Ebert and the new republic signed the armistice. -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

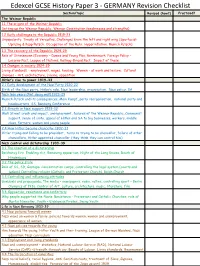

Edexcel GCSE History Paper 3 - GERMANY Revision Checklist Section/Topic Revised (How?) Practised? the Weimar Republic 1.1 the Origins of the Weimar Republic

Edexcel GCSE History Paper 3 - GERMANY Revision Checklist Section/topic Revised (how?) Practised? The Weimar Republic 1.1 The origins of the Weimar Republic Setting up the Weimar Republic, Weimar Constitution (weaknesses and strengths) 1.2 Early challenges to the Republic 1919-23 Unpopularity, Treaty of Versailles, Challenges from the left and right wing (Spartacist Uprising & Kapp Putsch, Occupation of the Ruhr, Hyperinflation, Munich Putsch) 1.3 The recovery of the Republic 1924-29 Role of Stresemann (Economy – Dawes and Young Plan, Rentenmark. Foreign Policy – Locarno Pact, League of Nations, Kellogg-Briand Pact. Impact of these. 1.4 Changes in society 1924-29 Living standards – employment, wages, housing. Women – at work and leisure. Cultural changes – Art, architecture, cinema, opposition Hitler’s rise to power 1919-33 2.1 Early development of the Nazi Party 1920-22 Birth of the Nazi party, Hitler’s role, Nazi leadership, organisation, Nazi policy, SA Nazi lean years (Not doing well) 1923-29 Munich Putsch and its consequences, Mein Kampf, party reorganisation, national party and headquarters, SS, Bamberg Conference 2.3 Growth in Nazi support 1929-32 Wall Street crash and impact, unemployment, failures of the Weimar Republic, Communist support, sense of unity, appeal of Hitler and SA to big businesses, workers, middle class, farmers, women and young people 2.4 How Hitler became chancellor 1932-33 Hitler trying and failing to be president, turns to trying to be chancellor, failure of other chancellors, Hitler appointed chancellor (they think they can control him) Nazi control and dictatorship 1933-39 3.1 The creation of a dictatorship Reichstag fire. -

Germany Depth Study Content Revision Guide 1

Germany Depth Study Content Revision Guide 1. Armistice – November 1918 • Kaiser abdicated (gave up being King) 10th November • Ebert signed the German surrender (admitted defeat) 11th November • Many people, especially soldiers, were angry that they had been betrayed by the government • Ebert was known as one of the ‘November Criminals’ • The ‘Dolchtosslegende’ (‘Stab in the Back’ myth) developed as a consequence • Jews were also blamed for the Armistice – people felt they should have used their influence to help the government and the country to keep fighting 2. Spartacist Uprising, January 1919 Events: • The Spartacists were a LEFT WING Communist group who tried to overthrow Ebert • 100,000 people protested – the army REFUSED to help Ebert out because of the Armistice • Ebert called on the FREIKORPS – ex-army, had their own weapons – to sort it out • The Freikorps didn’t like Ebert, but hated communists more, so they helped • The Spartacist leaders (Liebknecht and Luxemberg) were killed • Uprising failed after a week long street fight in Berlin Effects: • Negative/Political: Showed that Ebert was weak, had no authority over his own army, and that some people did not support him • Positive/political: Ebert was able to defend his own country and after calling an election to make himself legitimate, began to establish some laws over Germany 3. Treaty of Versailles, June 1919 Terms: LAND ARMY • 13% of land lost, including… • German army reduced to 100,000 soldiers (from - Alsace-Lorraine to France 1.5M before WW1) - Saarland coalfields (50% of Germany’s coal) • No air force/No submarines • 10% of population displaced • Maximum of 6 battleships • Rhineland (border between France and Germany = demilitarised) MONEY BLAME • $6.6 billion reparations to be paid to Belgium and • ‘War Guilt Clase’ (Article 231) – Germany had to France for the damage accept total responsibility for losing WW1 Effects: • Political – made Ebert’s position difficult, Germans saw him as a traitor. -

Topic Booklet Weimar and Nazi Germany

Option 31 Topic booklet Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1918–39 GCSE (9-1) History Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9-1) in History (1HI0) Contents 1. Overview 2 1.1 Assessment 2 2. Content guidance 4 2.1 Summary of content 4 2.2 Content exemplification and mapping 6 3. Student timeline 16 4. Resources 18 4.1 Resources for students 18 4.2 Resources for teachers 20 © Pearson 2015 1. Overview 1. Overview In contrast to the proud, patriotic and celebratory mood with which Germany entered the First World War in 1914, it was a shocked and defeated Germany in 1918 that then bitterly resented its treatment by the victorious allies with the Treaty of Versailles. A new, democratic Weimar Germany was burdened with severe political and economic dislocation and by 1923 faced the humiliating invasion by the French of its industrial centre of the Ruhr. However, a mixture of Stresemann’s work and more favourable international conditions allowed Weimar Germany to undergo a period known as ‘the Golden Years’ until the Wall Street Crash in 1929 had significant economic and thus political consequences for Weimar Germany. Immediately at the end of the First World War, the right wing of German politics were especially resentful at Germany’s defeat, at the peace treaty and at the new democratic style of government. Hitler had become leader of the National Socialist Workers’ Party. After having attempted coming to power by means of force in Munich in November 1923, Hitler determined to achieve power by democratic means. Once power had been achieved, democratic government could then be abandoned. -

The NSDAP and the German Working Class, 1925-1933

8 The NSDAP and the German Working Class, 1925-1933 PETER D. STACHURA Throughout the pre-1933 period, the National Socialist party (NSDAP) projected an image of being a broadly-based Volksbewegung whose aim was to restore the fortunes of all Germans regardless of status or class. The party's ideological and propagandistic appeal was modelled to attract to the swastika as many sections of \~eimar society as possible. This approach made sense, after all, if the NSDAP were to exoand its electoral constituency to the point where it could establish a popular mandate for power. Following the unsuccessful 11unich putsch in 1923, Hitler renounced violent, revolutionary tactics in favor of a long-term parliamentary strategy that would allow him to assume governmental responsibility within the letter of the law. In the end, of course, the NSDAP did win power legally even if it constantly violated the spirit of the law. While failing to attain an overall majority in Reichstag elections in July and November 1932, the NSDAP, despite showing incipient signs of having passed its peak, was ultimately brought into the government, thanks to the last-minute interventionist power politics of industrial and agrarian elitist groups representing propertied, nationalist, and Protestant Germany.l Contrary to Joseph Goebbels's assertion in early 1933 that the !1achtergreifung signified "a revolution of a workers' movement,"2 empirical historical inquiry has established that by 1933 the NSDAP drew its electoral support overwhelmingly from the small town and rural Protestant Mittelstand, comprising men and women in roughly equal numbers, in northern, central, and eastern Germany.3 Although by 1930-31 the lower 11ittelstand, particularly of the "old" or traditional type, predominated among the party's voters and members, the upper Hittelstand were beginning to flock into the ranks in ever-increasing numbers in 1932,4 thus making the NSDAP more of a catch-all movement of middle-class protest, a movement of bourgeois integration. -

Hitler's Rise to Power, 1919-33

HISTORY – YEAR 11 – HITLER’S RISE TO POWER, 1919- 33 A KEY DATES C KEY TERMS/CONCEPTS 1 Sept 1919 Hitler joins German Workers Party. German Workers Party – later the NSDAP or ‘Nazi’ Party. A 1 DAP right-wing, nationalist political organisation. 2 24th Feb 1920 Twenty-Five Point programme. Twenty-Five Point A set of 25 beliefs and policies that the Nazis would introduce 3 Oct 1921 SA formed. 2 Programme if elected. It included anti-Semitic points. 4 Nov 1923 Munich Putsch – Hitler arrested. Hitler’s private army of stormtroopers, known as the 3 SA 5 1924 Hitler writes ‘Mein Kampf’ in prison. ‘brownshirts’. 6 Feb 1926 Bamberg conference – Führerprinzip. Hitler’s failed attempt to seize power in Munich. It gave the 4 Munich Putsch Nazis a great deal of publicity. 7 Late 1929 Wall Street Crash. Meaning ‘My Struggle’ – book written by Hitler in prison 14th Sept 5 Mein Kampf 8 Nazis win 107 seats in September elections. outlining his vision for making Germany strong internationally. 1930 Bamberg Held to establish the idea of Fuhrerprinzip – the Fuhrer as 31st July 6 9 Nazis win 230 seats as unemployment rises Conference sole leader. 1932 Reached over 6 million in 1933. Many turned to extreme 10 30th Jan 1933 Hitler becomes Chancellor of Germany. 7 Unemployment B KEY PEOPLE parties. 1 Anton Drexler Founded the Nazi Party and co-wrote the 25 points. Many workers supported the Communist Party. Businesses 8 Communist Party supported the Nazis as a result and funded Hitler’s campaign. 2 Adolf Hitler Leader of NSDAP (Nazi Party).