Session 8A: Joint AIA/SCS Colloquium (Inter-) Regional Networks in Hellenistic Eurasia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Image – Action – Space

Image – Action – Space IMAGE – ACTION – SPACE SITUATING THE SCREEN IN VISUAL PRACTICE Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner (Eds.) This publication was made possible by the Image Knowledge Gestaltung. An Interdisciplinary Laboratory Cluster of Excellence at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (EXC 1027/1) with financial support from the German Research Foundation as part of the Excellence Initiative. The editors like to thank Sarah Scheidmantel, Paul Schulmeister, Lisa Weber as well as Jacob Watson, Roisin Cronin and Stefan Ernsting (Translabor GbR) for their help in editing and proofreading the texts. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Copyrights for figures have been acknowledged according to best knowledge and ability. In case of legal claims please contact the editors. ISBN 978-3-11-046366-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-046497-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-046377-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956404 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche National bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org and https://www.oapen.org. Cover illustration: Malte Euler Typesetting and design: Andreas Eberlein, aromaBerlin Printing and binding: Beltz Bad Langensalza GmbH, Bad Langensalza Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhalt 7 Editorial 115 Nina Franz and Moritz Queisner Image – Action – Space. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Articles and Also and Instrumental Development

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 12631–12686, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-12631-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A review of experimental techniques for aerosol hygroscopicity studies Mingjin Tang1, Chak K. Chan2, Yong Jie Li3, Hang Su4,5, Qingxin Ma6, Zhijun Wu7, Guohua Zhang1, Zhe Wang8, Maofa Ge9, Min Hu7, Hong He6,10,11, and Xinming Wang1,10,11 1State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environmental Protection and Resources Utilization, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China 2School of Energy and Environment, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China 3Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Macau, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau, China 4Center for Air Pollution and Climate Change Research, Institute for Environmental and Climate Research, Jinan University, Guangzhou 511443, China 5Department of Multiphase Chemistry, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz 55118, Germany 6State Key Joint Laboratory of Environment Simulation and Pollution Control, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085, China 7State Key Joint Laboratory of Environmental Simulation and Pollution Control, College of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 8Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China 9State Key Laboratory for Structural Chemistry of Unstable and Stable Species, Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China 10University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 11Center for Excellence in Regional Atmospheric Environment, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiamen 361021, China Correspondence: Mingjin Tang ([email protected]) and Chak K. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Ancient Lamps in the J. Paul Getty Museum

ANCIENT LAMPS THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Ancient Lamps in the J. Paul Getty Museum presents over six hundred lamps made in production centers that were active across the ancient Mediterranean world between 800 B.C. and A.D. 800. Notable for their marvelous variety—from simple clay saucers GETTYIN THE PAUL J. MUSEUM that held just oil and a wick to elaborate figural lighting fixtures in bronze and precious metals— the Getty lamps display a number of unprecedented shapes and decors. Most were made in Roman workshops, which met the ubiquitous need for portable illumination in residences, public spaces, religious sanctuaries, and graves. The omnipresent oil lamp is a font of popular imagery, illustrating myths, nature, and the activities and entertainments of daily life in antiquity. Presenting a largely unpublished collection, this extensive catalogue is ` an invaluable resource for specialists in lychnology, art history, and archaeology. Front cover: Detail of cat. 86 BUSSIÈRE AND LINDROS WOHL Back cover: Cat. 155 Jean Bussière was an associate researcher with UPR 217 CNRS, Antiquités africaines and was also from getty publications associated with UMR 140-390 CNRS Lattes, Ancient Terracottas from South Italy and Sicily University of Montpellier. His publications include in the J. Paul Getty Museum Lampes antiques d'Algérie and Lampes antiques de Maria Lucia Ferruzza Roman Mosaics in the J. Paul Getty Museum Méditerranée: La collection Rivel, in collaboration Alexis Belis with Jean-Claude Rivel. Birgitta Lindros Wohl is professor emeritus of Art History and Classics at California State University, Northridge. Her excavations include sites in her native Sweden as well as Italy and Greece, the latter at Isthmia, where she is still active. -

Installers.Pdf

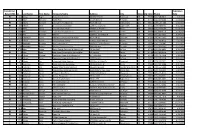

Initial (I) or Expiration Recert (RI) Id Last Name First Sept Name Company Name Address City State Zip Code Phone Date RI 212 Abbas Roger Abbas Construction 6827 NE 33rd St Redmond OR 97756 (541) 548-6812 2/3/2024 I 2888 Adair Benjamin Septic Pros 1751 N Main st Prineville OR 97754 (541) 359-8466 5/10/2024 RI 727 Adams Kenneth Ken Adams Plumbing Inc 906 N 9th Ave Walla Walla WA 99362 (509) 529-7389 6/23/2023 RI 884 Adcock Dean Tri County Construction 22987 SE Dowty Rd Eagle Creek OR 97022 (503) 948-0491 9/25/2023 I 2592 Adelt Georg Cascade Valley Septic 17360 Star Thistle Ln Bend OR 97703 (541) 337-4145 11/18/2022 I 2994 Agee Jetamiah Leavn Trax Excavation LLC 50020 Collar Dr. La Pine OR 97739 (541) 640-3115 9/13/2024 I 2502 Aho Brennon BRX Inc 33887 SE Columbus St Albany OR 97322 (541) 953-7375 6/24/2022 I 2392 Albertson Adam Albertson Construction & Repair 907 N 6th St Lakeview OR 97630 (541) 417-1025 12/3/2021 RI 831 Albion Justin Poe's Backhoe Service 6590 SE Seven Mile Ln Albany OR 97322 (541) 401-8752 7/25/2022 I 2732 Alexander Brandon Blux Excavation LLC 10150 SE Golden Eagle Dr Prineville OR 97754 (541) 233-9682 9/21/2023 RI 144 Alexander Robert Red Hat Construction, Inc. 560 SW B Ave Corvallis OR 97333 (541) 753-2902 2/17/2024 I 2733 Allen Justan South County Concrete & Asphalt, LLC PO Box 2487 La Pine OR 97739 (541) 536-4624 9/21/2023 RI 74 Alley Dale Back Street Construction Corporation PO Box 350 Culver OR 97734 (541) 480-0516 2/17/2024 I 2449 Allison Michael Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 I 2448 Allison Tisha Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 RI 679 Alman Jay Integrated Water Services 4001 North Valley Dr. -

Moon Exhibit Catalog

Moon Exhibition Catalog July 20 - December 20, 2019 University of Arizona Libraries Special Collections Curated by Molly Stothert-Maurer, Archivist & History of Science Curator and Christopher Cokinos, Associate Professor of English Introduction It is always there, at least in our lives, the Moon, lit or dark, seen or not, a cold dead rocky globe of pits and rubble, of mountains and scars, our helpful companion in gravity and evolution, symbol, territory, night light during its days’ long lunar morning, silent siren for nocturnal predators, werewolves, lovers, geologists, for a time and perhaps again, perhaps for good, the astronauts, new lunar denizens. The Moon is visually sublime and scientifically compelling. It’s up there whether you live in the city or out in the country. With your own eyes, with binoculars, with a telescope, you can set sail for it. For stargazers and astronomers, the Moon is sometimes a bane bleaching out the fainter and far-flung gray-green galaxies and nebulae one might otherwise see in the eyepieces of backyard telescopes or on the computer screens of professional observatories. But we are rediscovering the Moon’s capacity to instill wonder, especially because it is not the barren place we once thought. Water ice exists on the Moon, water is locked up in its surface, and some researchers have suggested the early Moon had warm surface oceans in which microbial life might have evolved. At a time when we are looking back at the 1960s’ race to the Moon, we should also look ahead to what our scientific and even cultural future with the Moon might be. -

Comments by Referees Are in Blue. Our Replies Are in Black. Changes to the Manuscript Are Highlighted in Red Both in Here and in the Revised Manuscript

Comments by referees are in blue. Our replies are in black. Changes to the manuscript are highlighted in red both in here and in the revised manuscript. The work is important and of relevance to the readership. The authors present a review of hygroscopicity measurements as it pertains to the atmosphere and also orthogonal scientific fields (surface science, heterogeneous catalysis, geochemistry/astrochemistry, pharmaceutical and food science, etc). Thus the publication will be of interest to the ACP readership and other fields. The authors have done a good job to describe “non-conventional atmospheric” hygroscopicity measurements. That is they provide an overview of comprehensive laboratory techniques that due to time or spatial resolution is not necessarily applied to field studies. For instance, the spectroscopy section is quite thorough and provides information on the numerous spectroscopy techniques that have been applied in controlled laboratory settings. The review is useful in that it provides a current overview of the current state of technology for hygroscopicity. However, the paper does not include a review of the theoretical hygroscopicity equations (although, I do not think that this is the purpose of the manuscript). Furthermore, I was quite disappointed to find that CCN and IN techniques were not discussed at all and perhaps this omission should be reflected in the title. E.g. "A review of experimental techniques for unsaturated aerosol hygroscopicity studies". Regardless of this disappointment, I highly recommend the work for publication in ACP. The work will be cited heavily in the future. The following are a few concepts and ideas that may strengthen and or clarify ideas in the manuscript. -

Communications of the LUNAR and PLANETARY LABORATORY

Communications of the LUNAR AND PLANETARY LABORATORY Number 70 Volume 5 Part 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1966 Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory These Communications contain the shorter publications and reports by the staff of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. They may be either original contributions, reprints of articles published in professional journals, preliminary reports, or announcements. Tabular material too bulky or specialized for regular journals is included if future use of such material appears to warrant it. The Communications are issued as separate numbers, but they are paged and indexed by volumes. The Communications are mailed to observatories and to laboratories known to be engaged in planetary, interplanetary or geophysical research in exchange for their reports and publica- tions. The University of Arizona Press can supply at cost copies to other libraries and interested persons. The University of Arizona GERARD P. KUIPER, Director Tucson, Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory Published with the support of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Library of Congress Catalog Number 62-63619 NO. 70 THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT IV by D. W. G. ARTHUR, RUTH H. PELLICORI, AND C. A. WOOD May25,1966 , ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central peak information, and state of completeness are listed for each discernible crater with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km in the fourth lunar quadrant. The catalog contains about 8,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. hiS Communication is the fourth and final part of listed in the catalog nor shown in the accompanying e System of Lunar Craters, which is a_calalag maps. -

John Ashbery 125 Part Twelve the Voyages of John Matthias 133

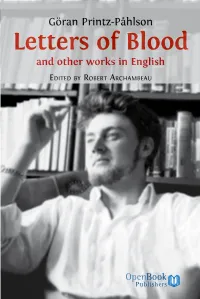

Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/86 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. openbookpublishers.com/product/86#copyright Further details about CC BY-NC-ND licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ All the external links were active on 02/5/2016 unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume can be found at https://www. -

LUNAR SECTION CIRCULAR Vol.56 No.6 June 2019

LUNAR SECTION CIRCULAR Vol. 56 No. 6 June 2019 _________________________________________ FROM THE DIRECTOR We open this issue with some excellent news. The IAU has officially named Minor Planet 1999 TG12 after our lunar domes coordinator Raf Lena. The body is a main belt asteroid and will now be termed ‘102224 Raffaellolena’ in recognition of Raf’s great contribution to lunar studies. The IAU citation reads: ‘Raffaello Lena (b. 1959) is an Italian lunar observer. He founded Selenology Today, a journal that has produced high quality amateur lunar studies. He is the Lunar Domes Coordinator of the British Astronomical Association’. Raffaello Lena We congratulate Raf on this achievement and continue to value his association with our Section. A further piece of excellent news is that our hard-working Website Manager Stuart Morris has completed the huge task of digitising and uploading the complete run of Lunar Section Circulars from the very first issue in December 1965. There were sporadic newsletter issues before then, but the LSC in its current form began in 1965, under the directorship of Patrick Moore and ably edited by Phil Ringsdore. Along with past issues of The Moon, also available online, it provides an unparalleled insight into more than half a century’s history of the BAA Lunar Section. The Section is immensely grateful to Stuart for making this valuable resource available to BAA members. To view and download issues see the Lunar Section website at: https://britastro.org/downloads/10167 You will need to log in as a BAA member. We are now entering the summer period when the Moon is low in northern skies and darkness is a rare commodity.