Anthropologiai Közlemények 28. (1984)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Test-Booklet

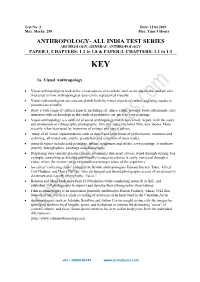

Test No: 2 Date: 12.01.2019 Max. Marks: 250 Max. Time 3 Hours ANTHROPOLOGY- ALL INDIA TEST SERIES ARCHEOLOGY, GENERAL ANTHROPOLOGY PAPER-1, CHAPTERS- 1.1 to 1.8 & PAPER-2, CHAPTERS- 1.1 to 1.3 KEY 1a. Visual Anthropology • Visual anthropologists look at the visual aspects of a culture, such as art and media, and are also interested in how anthropological data can be represented visually, • Visual anthropologists are concerned with both the visual aspects of culture and using media to present data visually. • study a wide range of cultural aspects, including art, dance, ritual, jewelry, body adornments; also intersects with archaeology in the study of prehistoric art, such as cave paintings • Visual anthropology is a subfield of social anthropology that is concerned, in part, with the study and production of ethnographic photography, film and, since the mid-1990s, new media. More recently it has been used by historians of science and visual culture. • study of all visual representations such as dance and other kinds of performance, museums and archiving, all visual arts, and the production and reception of mass media. • research topics include sand paintings, tattoos, sculptures and reliefs, cave paintings, scrimshaw, jewelry, hieroglyphics, paintings and photographs • Displaying data visually presents unique advantages that aren't always found through writing. For example, something as detailed and visually-focused as a dance is easily conveyed through a video, where the viewer can get a sometimes stronger sense of the experience • So-called "collecting clubs" included the British anthropologists Edward Burnett Tylor, Alfred Cort Haddon, and Henry Balfour, who exchanged and shared photographs as part of an attempt to document and classify ethnographic "races." • Bateson and Mead took more than 25,000 photos while conducting research in Bali, and published 759 photographs to support and develop their ethnographic observations. -

NARTAMONGЖ 2013 Vol. Х, N 1, 2 F. R. ALLCHIN ARCHEOLOGICAL and LANGUAGE-HISTORICAL EVIDENCE for the MOVEMENT of INDO

NARTAMONGÆ 2013 Vol. Х, N 1, 2 F. R. ALLCHIN ARCHEOLOGICAL AND LANGUAGE-HISTORICAL EVIDENCE FOR THE MOVEMENT OF INDO-ARYAN SPEAKING PEOPLES INTO SOUTH ASIA The present Symposium serves a useful purpose in focusing our attention upon the difficulties encountered in recognising the movements of peoples from archeological evidence. One of the reassuring aspects of the broad inter- national approach which is experienced in such a gathering is that it serves to show the common nature of the problems that confront us in trying to re- construct the movements of the Indo-Aryans and Iranians, whether in the South-Russian steppes or the steppes of Kazakhstan; the Caucasus or the southern parts of Middle Asia properly speaking; or in Iran, Afghanistan, Pa- kistan or India. Perhaps this is why there were recurrent themes in several pa- pers, and why echoes of what I was trying to express appeared also in the pa- pers of others, notably in those of B. A. Litvinsky and Y. Y. Kuzmina. In particular, there seems to be a need for a general hypothesis or model for these movements. Such a model must be inter-disciplinary, combining the more limited models derivable from archeological, historical, linguistic, anth- ropological and other categories of data. Strictly speaking, the several hypo- theses derived from each of these categories should first be formulated inde- pendently, and then as a second stage they should be systematically compared to one another. Only when there do not appear to be serious contradictions be- tween them should they be regarded as ready for incorporation into the general model. -

Aryans, Harvesters and Nomads (Thursday July 6 2.00 – 5.00) Convenor: Prof

PANEL: Aryans, Harvesters and Nomads (Thursday July 6 2.00 – 5.00) Convenor: Prof. Asko Parpola: Department of Asian & African Studies University of Helsinki Excavations at Parwak, Chitral • Pakistan. Ihsan Ali: Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of NWFP & Muhammad Zahir: Lecturer, Government College, Peshawar The Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of NWFP, under the supervision of Prof. (Dr.) Ihsan Ali, Director, Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of NWFP, Peshawar has completed the first ever excavations in Chitral at the site of Parwak. The team included Muhammad Zahir, Lecturer, Government College, Peshawar and graduates of the Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar. Chitral, known throughout the world for its culture, traditions and scenic beauty, has many archaeological sites. The sites mostly ranging from 1800 B.C. to the early 600 B.C, are popularly known as Gandhara Grave Culture. Though brief surveys and explorations were conducted in the area earlier, but no excavations were conducted. The site of Parwak was discovered by a team of Archaeologists from Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of NWFP and Boston University, USA in a survey conducted in June 2003 under the direction of Prof. (Dr.) Ihsan Ali and Dr. Rafique Mughal. The site is at about 110 km north east of Chitral, near the town of Buni, on the right bank of river Chitral and set in a beautiful environment. The site measures 121 x 84 meter, divided in to three mounds. On comparative basis, the site is datable to the beginning of 2nd millennium BC and represents a culture, commonly known as Gandhara Grave Culture of the Aryans, known through graves and grave goods. -

Pre-Proto-Iranians of Afghanistan As Initiators of Sakta Tantrism: on the Scythian/Saka Affiliation of the Dasas, Nuristanis and Magadhans

Iranica Antiqua, vol. XXXVII, 2002 PRE-PROTO-IRANIANS OF AFGHANISTAN AS INITIATORS OF SAKTA TANTRISM: ON THE SCYTHIAN/SAKA AFFILIATION OF THE DASAS, NURISTANIS AND MAGADHANS BY Asko PARPOLA (Helsinki) 1. Introduction 1.1 Preliminary notice Professor C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky is a scholar striving at integrated understanding of wide-ranging historical processes, extending from Mesopotamia and Elam to Central Asia and the Indus Valley (cf. Lamberg- Karlovsky 1985; 1996) and even further, to the Altai. The present study has similar ambitions and deals with much the same area, although the approach is from the opposite direction, north to south. I am grateful to Dan Potts for the opportunity to present the paper in Karl's Festschrift. It extends and complements another recent essay of mine, ‘From the dialects of Old Indo-Aryan to Proto-Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian', to appear in a volume in the memory of Sir Harold Bailey (Parpola in press a). To com- pensate for that wider framework which otherwise would be missing here, the main conclusions are summarized (with some further elaboration) below in section 1.2. Some fundamental ideas elaborated here were presented for the first time in 1988 in a paper entitled ‘The coming of the Aryans to Iran and India and the cultural and ethnic identity of the Dasas’ (Parpola 1988). Briefly stated, I suggested that the fortresses of the inimical Dasas raided by ¤gvedic Aryans in the Indo-Iranian borderlands have an archaeological counterpart in the Bronze Age ‘temple-fort’ of Dashly-3 in northern Afghanistan, and that those fortresses were the venue of the autumnal festival of the protoform of Durga, the feline-escorted Hindu goddess of war and victory, who appears to be of ancient Near Eastern origin. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha)

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Ihsan Ali Muhammad Naeem Qazi Hazara University Mansehra NWFP – Pakistan 2008 Uploaded by [email protected] © Copy Rights reserved in favour of Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Editors: Ihsan Ali* Muhammad Naeem Qazi** Price: US $ 20/- Title: Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Frontispiece: Buddha Visiting Kashyapa Printed at: Khyber Printers, Small Industrial Estate, Kohat Road, Peshawar – Pakistan. Tel: (++92-91) 2325196 Fax: (++92-91) 5272407 E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence Address: Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Website: hu.edu.pk E-mail: [email protected] * Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Currently Vice Chancellor, Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan ** Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan CONTRIBUTORS 1. Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, Vice Chancellor Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2. Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 3. Ihsanullah Jan, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 4. Muhammad Ashfaq, University Museum, Hazara University 5. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 6. Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 7. Muhammad Imran Khan, Archaeologist, Charsadda, Pakistan 8. Muhammad Haroon, Archaeologist, Mardan, Pakistan III ABBREVIATIONS A.D.F.C. Archaeology Department, Frontier Circle A.S.I. Archaeological Survery of India A.S.I.A.R. Archaeological Survery of India, Annual Report D.G.A. Director General of Archaeology E.G.A.C. Exhibition of the German Art Council I.G.P. Inspector General Police IsMEO Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente P.M. -

Archaeology As a Source of Shared History: a Case Study of Ancient Kashmir

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Knowledge Repository Open Network Archaeology as a Source of Shared History: A Case Study of Ancient Kashmir THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (M.Phil) IN HISTORY By SHAJER US SHAFIQ JAN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Prof. PARVEEZ AHMAD P.G. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR, HAZRATBAL SRINAGAR, 190006. 2012 Introduction Archaeology does not only constitute the sole source of the 99% of the total time of man on this planet and an important supplementary source of the period that followed invention of writing, but, more than that, it helps us to write a unitary history of mankind by throwing light on the origin, growth, diffusion and transmission of humans and their culture. Deeply pained by the disastrous consequences of perverted nationalism, which resulted into two heinous world wars, A. J. Toynbee embarked on the ambitious project of demolishing the Euro-centric view of history, employed by the colonial historians as an instrument to justify imperialism. And in this great human cause he was supported by archaeology. A meaningful universal view of history was possible only by bringing to focus the contributions made by different western and non-western cultures to the human civilization. Archaeology poured out profusely in favour of plural sources of human civilization which emboldened Toynbee to sail against the tide—a fact which he acknowledges radiantly. It has been empirically proven that cultures have evolved and grown owing to plural causative factors having their origins both within and outside their local geographical borders. -

Pakistan Archaeology

Pakistan Archaeology Number 32-2017 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN ISLAMABAD i Pakistan Archaeology Number 32-2017 ii Pakistan Archaeology Number 32-2017 Chief Editor Abdul Azeem Editor Mahmood-ul-Hasan DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN ISLAMABAD iii BOARD OF EDITORS Dr. Abdul Azeem Dr. Aurore DIDIER Director, Director, Department of Archaeology and French Archaeological Mission in Museums, Government of Pakistan, the Indus Basin Islamabad CNRS-UMR 7041/ArScAn 21, allee de l’Universite 92023 Nanterre Cedex-France Mahmood-ul-Hasan Dr. Chongfeng Li Assistant Director, Professor of Buddhist Art and Department of Archaeology and Archaeology, Museums, Government of Pakistan, Peking University, Islamabad School of Archaeology and Museology, Beijing, China Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Dr. Luca M. Olivieri Khan Director, Former Director, Taxila Institute of Italian Archaeological Mission in Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam Pakistan University, Plazzo Baleani, Islamabad, Pakistan Corso Vittorio Emanuele, Rome, Italy Mr. Saleem-ul-Haq Dr. Pia Brancaccio Former Director, Associate Professor, Department of Archaeology and Department of Art and Art History, Museums, Government of Punjab, Drexel University, Lahore, Pakistan Westphal College of Media Arts and Design, Philadelphia, USA iv © Department of Archaeology and Museums, Pakistan 2017 ISSN 0078-7868 Price in Pakistan: Rs. 1000.00 Foreign Price U. S. $ 40 Published by The Department of Archaeology and Museums Government of Pakistan, Islamabad Printed by Graphics Point Pak Media Foundation Building, G-8 Mrkaz, Islamabad, Pakistan v CONTENTS Illustrations……………………………………………….. vii Editorial…………………………………………………... xii Explorations Discovery of Rock art in Azad Jammu and Kashmir 15 M. Ashraf Khan and Sundus Aslam Khan and Saqib Raza…….. -

In Memory of Professor Ahmad Hasan Dani Hisservices, Contribution Achievements& Guirahim Khan

AndentPakistan, Vol. XX-2009 261 In memory of Professor Ahmad Hasan Dani HisServices, Contribution Achievements& GuiRahim Khan It ismy honour to enlistand highlightthe services and contributions of LateProfessor Ahmad Hasan Dani, who recently died on January26, 2009 at the age of 88 years. He led a very activelife and got great fame.His personality is well known in the field of archaeology, art and architecture, history, epigraphy and numismatics. He was a world reputed scholar and there is no need to write about his personality or his work. His servicesare so longer and contributionsare too muchthat he himselfdidn't remember andrecord these figures. It was in the last year (2008) of his life that his wife requested Prof. M. Farooq Swati (Chairman), Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar to provide herthe list of published work of Prof. Ahmad Hasan Dani. The said taskwas given to me, which was accomplished and provided. It was appreciated and properly acknowledged by Mrs. Dani. Many people have written a lot about him, his contributionsand achievements.Similarly his biography and services were greatly highlightedin the many reputed daily newspapers and magazines after his death. In view of his extensive contributions it was not possible to mentionhere all thesethings in detailed discussion which need to be published in a book form. Here theauthor has attempted to compile a complete profileof Late Prof. AhmadHasan Dani alongwith a detailedbibliography of hispublished work in theform of listedcateg oriesdescribed below. ServiceExperience -

India: the Ancient Past: a History of the Indian Sub-Continent from C. 7000 Bc to Ad 1200

India: The Ancient Past ‘Burjor Avari’s balanced and well-researched book is a most reliable guide to the period of Indian history that it covers. It displays consider- able mastery of primary and secondary literature and distils it into a wonderfully lucid exposition. This book should be of interest to both lay readers and academic experts.’ Lord Bhikhu Parekh, University of Westminster A clear and systematic introduction to the rich story of the Indian past from early pre-history up until the beginning of the second millennium, this survey provides a fascinating account of the early development of Indian culture and civilisation. The study covers topics such as the Harappan Civilisation, the rise of Hindu culture, the influx of Islam from the eighth to the twelfth century, and key empires, states and dynasties. Through such topics and their histori ographies, the book engages with methodological and controversial issues. Features of this richly illustrated guide also include a range of maps to illustrate different time periods and geographical regions. Selected source extracts for review and reflection can be found at the end of every chapter, together with questions for discussion. India: The Ancient Past provides comprehensive coverage of the political, spiritual, cultural and geographical history of India in a uniquely accessible manner that will appeal both to students and to those with a general interest in Indian history. Burjor Avari was born in India in 1938, spent his childhood in Kenya and Zanzibar, graduated in history at Manchester University and was trained as a teacher at the Oxford University Institute of Education. -

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Editors:Editors:Editors: Ihsan Ali*

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Editors:Editors:Editors: Ihsan Ali* Muhammad Naeem Qazi** Price: US $ 20/- Title:Title:Title: Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Frontispiece: Buddha Visiting Kashyapa Correspondence Address: Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Website: hu.edu.pk E-mail: [email protected] * Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Currently Vice Chancellor, Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan ** Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan CONTRIBUTORS 1. Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, Vice Chancellor Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2. Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 3. Ihsanullah Jan, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 4. Muhammad Ashfaq, University Museum, Hazara University 5. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 6. Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 7. Muhammad Imran Khan, Archaeologist, Charsadda, Pakistan 8. Muhammad Haroon, Archaeologist, Mardan, Pakistan III ABBREVIATIONS A.D.F.C. Archaeology Department, Frontier Circle A.S.I. Archaeological Survery of India A.S.I.A.R. Archaeological Survery of India, Annual Report D.G.A. Director General of Archaeology E.G.A.C. Exhibition of the German Art Council I.G.P. Inspector General Police IsMEO Instituto Italiano -

Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks Dynamics in the History of Religion

Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks Dynamics in the History of Religion Editor-in-Chief Volkhard Krech Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany Advisory Board Jan Assmann – Christopher Beckwith – Rémi Brague José Casanova – Angelos Chaniotis – Peter Schäfer Peter Skilling – Guy Stroumsa – Boudewijn Walraven VOLUME 2 Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks Mobility and Exchange within and beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia By Jason Neelis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the cc-by-nc License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Detail of the Śibi Jātaka in a petroglyph from Shatial, northern Pakistan (from Ditte Bandini-König and Gérard Fussman, Die Felsbildstation Shatial. Materialien zur Archäologie der Nordgebiete Pakistans 2. Mainz: P. von Zabern, 1997, plate Vb). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Neelis, Jason Emmanuel. Early Buddhist transmission and trade networks : mobility and exchange within and beyond the northwestern borderlands of South Asia / By Jason Neelis. p. cm. — (Dynamics in the history of religion ; v. 2) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Buddhist geography—Asia. 2. Trade routes—Asia—History. 3. Buddhists—Travel—Asia. I. Title. II. Series. BQ270.N44 2010 294.3’7209021—dc22 2010028032 ISSN 1878-8106 ISBN 978 90 04 18159 5 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands.