Borders. Contemporary Middle Eastern Art and Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Am Yisrael: a Resource Guide to Exploring the Many Faces of the Jewish People

Am Yisrael: A Resource Guide to Exploring the Many Faces of the Jewish People Prepared by Congregation Beth Adam and OurJewishCommunity.org with support from The Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati Table of Contents A Letter to Grownups ....................................................... Page 1 Am Yisrael: One Big Jewish Family ...................................... Page 2 Where Jews Live .............................................................. Page 3 What Jews Look Like ......................................................... Page 4 What Jews Wear ............................................................... Pages 5-8 What Jews Eat ................................................................ Page 9 Fun Jewish Recipes from Around the World ........................... Pages 10-12 I Love Being Jewish ......................................................... Page 13 Discussion Generating Activities ........................................ Pages 14-15 Discussion Questions ....................................................... Page 16 Jewish Diversity Songs ..................................................... Page 17 Coloring Book Pages ........................................................ Pages 18-29 Acknowledgments .......................................................... Page 30 Letter to Grownups When you think of Jews, what do you picture? What do they eat? What language do they speak? How do they dress? What makes them unique? There are so many ways to be Jewish, and so many different Jewish cultures around the world. -

Religious Head Covers and Other Articles of Faith Number SO-12-03 Effective Date January 27, 2012 DISTRICT of COLUMBIA

SPECIAL ORDER Title Religious Head Covers and Other Articles of Faith Number SO-12-03 Effective Date January 27, 2012 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA I. Policy Page 1 II. Definitions Page 1 III. Procedures Page 2 III.A Stops and Frisks Page 2 III.B Prisoner Processing Page 3 IV. Cross References Page 4 I. POLICY It is the policy of the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) to ensure that members of the MPD abide by laws that require the Department to make reasonable accommodations for the religious beliefs of those with whom its members interact in their official capacities. Thus, members of the MPD shall treat persons wearing religious head coverings or other articles of faith in a manner that is professional, respectful, and courteous. In general, persons wearing religious head coverings or other articles of faith shall be permitted to continue wearing them except when removal or confiscation is reasonably required for reasons of safety or security. II. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of this special order, the following terms shall have the meanings designated: 1. Member – Sworn or civilian employee or a member of the Reserve Corps. 2. Religious Head Covering – Articles worn on the head for religious purposes. They include, but are not limited to: a. Kippah (yarmulke) – Religious head covering worn by orthodox Jewish men; b. Kufi – Religious head covering worn by Christians, African Jews, and Muslims in West Africa and African Diaspora; RELIGIOUS HEAD COVERS AND OTHER ARTICLES OF FAITH (SO–12–03) 2 of 4 c. Hijab – Head scarf or covering worn by Muslim women; d. -

Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco

sustainability Article Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco Teresa Gil-Piqueras * and Pablo Rodríguez-Navarro Centro de Investigación en Arquitectura, Patrimonio y Gestión para el Desarrollo Sostenible–PEGASO, Universitat Politècnica de València, Cno. de Vera, s/n, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article is presented after ten years of research on the earthen architecture of southeast- ern Morocco, more specifically that of the natural axis connecting the cities of Midelt and Er-Rachidia, located North and South of the Moroccan northern High Atlas. The typology studied is called ksar (ksour, pl.). Throughout various research projects, we have been able to explore this territory, documenting in field sheets the characteristics of a total of 30 ksour in the Outat valley, 20 in the mountain range and 53 in the Mdagra oasis. The objective of the present work is to analyze, through qualitative and quantitative data, the main characteristics of this vernacular architecture as a perfect example of an environmentally respectful habitat, obtaining concrete data on its traditional character and its sustainability. The methodology followed is based on case studies and, as a result, we have obtained a typological classification of the ksour of this region and their relationship with the territory, as well as the social, functional, defensive, productive, and building characteristics that define them. Knowing and puttin in value this vernacular heritage is the first step towards protecting it and to show our commitment to future generations. Keywords: ksar; vernacular architecture; rammed earth; Morocco; typologies; oasis; High Atlas; sustainable traditional architecture Citation: Gil-Piqueras, T.; Rodríguez-Navarro, P. -

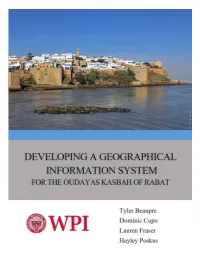

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat An Interactive Qualifying Project (IQP) Proposal submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelors of Science in cooperation with The Prefecture of Rabat Submitted by: Project Advisors: Tyler Beaupre Professor Ingrid Shockey Dominic Cupo Professor Gbetonmasse Somasse Lauren Fraser Hayley Poskus Submitted to: Mr. Hammadi Houra, Sponsor Liaison Submitted on October 12th, 2016 ABSTRACT An accurate map of a city is essential for supplementing tourist traffic and management by the local government. The city of Rabat was lacking such a map for the Kasbah of the Oudayas. With the assistance of the Prefecture of Rabat, we created a Geographical Information System (GIS) for that section of the medina using QGIS software. Within this GIS, we mapped the area, added historical landmarks and tourist attractions, and created a walking tour of the Oudayas Kasbah. This prototype remains expandable, allowing the prefecture to extend the system to all the city of Rabat. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In 2012, the city of Rabat, Morocco was awarded the status of a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site for integrating both Western Modernism and Arabo-Muslim history, creating a unique juxtaposition of cultures (UNESCO, 2016). The Kasbah of the Oudayas, a twelfth century fortress in the city, exemplifies this connection. A view of the Bab Oudaya is shown below in Figure 1. It is a popular tourist attraction and has assisted Rabat in bringing in an average of 500,000 tourists per year (World Bank, 2016). -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

Turkish Literature from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Turkish Literature

Turkish literature From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Turkish literature By category Epic tradition Orhon Dede Korkut Köroğlu Folk tradition Folk literature Folklore Ottoman era Poetry Prose Republican era Poetry Prose V T E A page from the Dîvân-ı Fuzûlî, the collected poems of the 16th-century Azerbaijanipoet Fuzûlî. Turkish literature (Turkish: Türk edebiyatı or Türk yazını) comprises both oral compositions and written texts in the Turkish language, either in its Ottoman form or in less exclusively literary forms, such as that spoken in the Republic of Turkey today. The Ottoman Turkish language, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, was influenced by Persian and Arabic and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. The history of the broader Turkic literature spans a period of nearly 1,300 years. The oldest extant records of written Turkic are the Orhon inscriptions, found in the Orhon River valley in central Mongolia and dating to the 7th century. Subsequent to this period, between the 9th and 11th centuries, there arose among the nomadic Turkic peoples of Central Asia a tradition of oral epics, such as the Book of Dede Korkut of the Oghuz Turks—the linguistic and cultural ancestors of the modern Turkish people—and the Manas epic of the Kyrgyz people. Beginning with the victory of the Seljuks at the Battle of Manzikert in the late 11th century, the Oghuz Turks began to settle in Anatolia, and in addition to the earlier oral traditions there arose a written literary tradition issuing largely—in terms of themes, genres, and styles— from Arabic and Persian literature. -

The Osborne Landtill Was Used for Many Years by Numerous Companies and Individuals in and Around Grove City Es a Place to Dispose of Unwanted Waste

SUMMARY OF COOPER INDUSTRIES, INC. INVOLVEMENT IN THE INVESTIGATION OF THE OSBORNE LANDFILL RI/FS The Osborne LandTill was used for many years by numerous companies and individuals in and around Grove City es a place to dispose of unwanted waste. In 1981, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources (DER) began their investigation of the need to clean up this site under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation end Liability Act (CERCLA or "Superfund"), 42 U.S.C. §9601 et sea. The efforts by U.S. EPA and Pennsylvania DER have involved the continuing cooperative effort of Cooper Industries, inc. whose C-B Reciprocating Division plant in Grove City used the Osborne Landfill to dispose of its foundry sand. EPA has identified parties who owned or operated this site, or who sent waste to it, including General Electric Corporation, Ashland Chemical Company, and Wolfe Iron & Metal Company (now Castle Iron & Metal). Typically, such parties, known as Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs), attempt to reach agreement with the government to perform the investigative and remedial work at their expense. This avoids the need for the government to spend Federal Superfund monies for the task. It also has been shown that these privately funded projects are done more efficiently and at less cost than those done by government contractors. This is in the best interests of these PRPs, because the government can require them to reimburse the Superfund for all such expenses that are performed consistently with the National Contingency Plan (NCP), 40 C.F.R. -

The Public Eye, Summer 2015

SUMMER 2015 The Public Eye When the Exception Is the Rule Christianity in the Religious Freedom Debates editor’s letter perspectives BY LInDsay BeyersTEIn THE PUBLIC EYE quarterly PUBLIsHER Tarso Luís Ramos Struggling to Get Church GUEsT EDIToR Kathryn Joyce Beyond the Hate Frame LAYoUT and State Right Jennifer Hall CoVER art Political Research Associates always strives to see both the trees and the forest: to go Asad Badat Whether it’s a spree killing, a vandalized mosque, or a beyond caricatures to provide fresh research and analysis on individual conservative bias attack on a queer teen, Americans are quick to chalk it PRInTInG activists and coalitions, but also to situate these actors in the larger infrastructure of Red Sun Press up to hate. The label “hate crime” invites us to blame over- the Right. The first piece in our Summer 2015 issue,“Beyond the Hate Frame” (page wrought individuals acting on extreme personal prejudice, EDIToRIAL BoARD , speaks to this ideal: an interview with Kay Whitlock and Michael Bronski, authors of 3) T.F. Charlton • Frederick Clarkson making it seem as if a small cadre of social deviants is our the new book Considering Hate, which explores how “the hate frame” obscures broader Alex DiBranco • Eric Ethington main obstacle to a peaceful society. In fact, such individu- issues of systemic violence. Kapya Kaoma • L. Cole Parke als are products of a society that endorses all kinds of vio- Tarso Luís Ramos • Spencer Sunshine lence against the very same groups who are targeted in hate As this issue is going to press, the Supreme Court has just announced its historic rul- Mariya Strauss crimes. -

Reasonable Plans. the Story of the Kasbah Du Toubkal

The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal MARRAKECH • MOROCCO DEREK WORKMAN The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal Marrakech • Morocco Derek WorkMan Second edition (2014) The information in this booklet can be used copyright free (without editorial changes) with a credit given to the Kasbah du Toubkal and/or Discover Ltd. For permission to make editorial changes please contact the Kasbah du Toubkal at [email protected], or tel. +44 (0)1883 744 392. Discover Ltd, Timbers, Oxted Road, Godstone, Surrey, RH9 8AD Photography: Alan Keohane, Derek Workman, Bonnie Riehl and others Book design/layout: Alison Rayner We are pleased to be a founding member of the prestigious National Geographic network Dedication Dreams are only the plans of the reasonable – dreamt by Discover realised by Omar and the Worker of Imlil (Inscription on a brass plaque at the entrance to the Kasbah du Toubkal) his booklet is dedicated to the people of Imlil, and to all those who Thelped bring the ‘reasonable plans’ to reality, whether through direct involvement with Discover Ltd. and the Kasbah du Toubkal, or by simply offering what they could along the way. Long may they continue to do so. And of course to all our guests who contribute through the five percent levy that makes our work in the community possible. CONTENTS IntroDuctIon .........................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 • The House on the Hill .......................................13 CHAPTER 2 • Taking Care of Business .................................29 CHAPTER 3 • one hand clapping .............................................47 CHAPTER 4 • An Association of Ideas ...................................57 CHAPTER 5 • The Work of Education For All ....................77 CHAPTER 6 • By Bike Through the High Atlas Mountains .......................................99 CHAPTER 7 • So Where Do We Go From Here? .......... -

The Healthcare Provider's Guide to Islamic Religious Practices

The Healthcare Provider’s Guide to Islamic Religious Practices About CAIR The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) is the largest American Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States. Its mission is to enhance understanding of Islam, protect civil rights, promote justice, and empower American Muslims. CAIR-California is the organization’s largest and oldest chapter, with offices in the Greater Los Angeles Area, the Sacramento Valley, San Diego, and the San Francisco Bay Area. According to demographers, Islam is the world’s second largest faith, with more than 1.6 billion adherents worldwide. It is the fastest-growing religion in the U.S., with one of the most diverse and dynamic communities, representing a variety of ethnic backgrounds, languages, and nationalities. Muslims are adding a new factor in the increasingly diverse character of patients in the health care system. The information in this booklet is designed to assist health care providers in developing policies and procedures aimed at the delivery of culturally competent patient care and to serve as a guide for the accommodation of the sincerely-held religious beliefs of some Muslim patients. It is intended as a general outline of religious practices and beliefs; individual applications of these observances may vary. Disclaimer: The materials contained herein are not intended to, and do not constitute legal advice. Readers should not act on the information provided without seeking professional legal counsel. Neither transmission nor receipt of these materials creates an attorney- client relationship between the author and the receiver. The information contained in this booklet is designed to educate healthcare providers about the sincerely-held and/or religiously mandated practices/beliefs of Muslim patients, which will assist providers in delivering culturally competent and effective patient care. -

Fulfilling the Promise of Free Exercise for All: Muslim Prisoner Accomodations in State Prisons

FREE EXERCISE REPORT JULY 2019 FULFILLING THE PROMISE OF FREE EXERCISE FOR ALL: Muslim Prisoner Accommodation in State Prisons 1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 4 I. METHODOLOGY: A Multi-Faceted Examination of Free Exercise Conditions in State Prisons ............................................................................................................................................. 7 A. State Religious Preference Data: 35-Jurisdiction Response ........................................................... 7 B. Database of 163 Recent Federal Cases Brought by Muslim Plaintiffs Alleging Free Exercise Violations ................................................................................................................................... 7 C. Religious Services Policies and Handbooks: 50-State Survey ........................................................ 8 II. BACKGROUND: Muslim Free Exercise History and Today’s Legal Regime ......................... 9 A. Early America and the Preservation of African Muslim Practices Under Conditions of Slavery ........................................................................................................................................ 9 B. Muslim Prisoners Spearhead Prison Conditions Litigation in the 1960s and 1970s .................... 10 C. Courts Reduce Prisoners’ Free Exercise Protection in the 80s and Early 90s .............................. 12 D. Congress -

An Analysis of Keffiyeh/Made in China

Last name 1 Student name English 110 Instructor name Date Art that Dictates Rather than Imitates: An Analysis of Keffiyeh/Made in China The keffiyeh, a checkered black and white scarf worn about the head or neck, is a symbol of Palestinian resistance that dates back to the 1930’s Arab Revolution against British occupation, and it represents the current struggle of Palestinians to control their identity and future in the face of Israeli occupation of their lands (Kreibaum). Dalia Taha, a Palestinian playwright who grew up in Ramallah, a city in the Palestinian West Bank (Moss) uses this powerful symbol in the title of her experimental play Keffiyeh/Made in China. Taha notes, “Art always challenges power structures” (Moss), and she does precisely this in her play. Palestine has had a tumultuous history of occupation and conflict. During the Arab-Israeli War in 1948, Nakba occurred, where thousands of Palestinians were displaced to create Israel. Nakba is the Arabic word for catastrophe, and that is how it is remembered by Palestinians. Thousands of Palestinians continue to die in the Israel- Palestine conflict, and many fight for the right to assert their identity (B'Tselem). In her play Keffiyeh/Made in China, Taha captures this on-going tumultuous struggle by combining historical events with experimental literary structure in order to humanize and educate the world about the Palestinian suffering in the wake of their occupation and to create awareness and support for them lest they be forgotten entirely. In one of the play’s acts called “60 Seconds,” Taha presents a character about to die as the result of a gunshot wound to the face, and she uses the technique of blending fiction Last name 2 with reality to connect the audience more directly to the plight of the Palestinians.