An Analysis of Keffiyeh/Made in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Am Yisrael: a Resource Guide to Exploring the Many Faces of the Jewish People

Am Yisrael: A Resource Guide to Exploring the Many Faces of the Jewish People Prepared by Congregation Beth Adam and OurJewishCommunity.org with support from The Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati Table of Contents A Letter to Grownups ....................................................... Page 1 Am Yisrael: One Big Jewish Family ...................................... Page 2 Where Jews Live .............................................................. Page 3 What Jews Look Like ......................................................... Page 4 What Jews Wear ............................................................... Pages 5-8 What Jews Eat ................................................................ Page 9 Fun Jewish Recipes from Around the World ........................... Pages 10-12 I Love Being Jewish ......................................................... Page 13 Discussion Generating Activities ........................................ Pages 14-15 Discussion Questions ....................................................... Page 16 Jewish Diversity Songs ..................................................... Page 17 Coloring Book Pages ........................................................ Pages 18-29 Acknowledgments .......................................................... Page 30 Letter to Grownups When you think of Jews, what do you picture? What do they eat? What language do they speak? How do they dress? What makes them unique? There are so many ways to be Jewish, and so many different Jewish cultures around the world. -

Turkish Literature from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Turkish Literature

Turkish literature From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Turkish literature By category Epic tradition Orhon Dede Korkut Köroğlu Folk tradition Folk literature Folklore Ottoman era Poetry Prose Republican era Poetry Prose V T E A page from the Dîvân-ı Fuzûlî, the collected poems of the 16th-century Azerbaijanipoet Fuzûlî. Turkish literature (Turkish: Türk edebiyatı or Türk yazını) comprises both oral compositions and written texts in the Turkish language, either in its Ottoman form or in less exclusively literary forms, such as that spoken in the Republic of Turkey today. The Ottoman Turkish language, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, was influenced by Persian and Arabic and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. The history of the broader Turkic literature spans a period of nearly 1,300 years. The oldest extant records of written Turkic are the Orhon inscriptions, found in the Orhon River valley in central Mongolia and dating to the 7th century. Subsequent to this period, between the 9th and 11th centuries, there arose among the nomadic Turkic peoples of Central Asia a tradition of oral epics, such as the Book of Dede Korkut of the Oghuz Turks—the linguistic and cultural ancestors of the modern Turkish people—and the Manas epic of the Kyrgyz people. Beginning with the victory of the Seljuks at the Battle of Manzikert in the late 11th century, the Oghuz Turks began to settle in Anatolia, and in addition to the earlier oral traditions there arose a written literary tradition issuing largely—in terms of themes, genres, and styles— from Arabic and Persian literature. -

The Public Eye, Summer 2015

SUMMER 2015 The Public Eye When the Exception Is the Rule Christianity in the Religious Freedom Debates editor’s letter perspectives BY LInDsay BeyersTEIn THE PUBLIC EYE quarterly PUBLIsHER Tarso Luís Ramos Struggling to Get Church GUEsT EDIToR Kathryn Joyce Beyond the Hate Frame LAYoUT and State Right Jennifer Hall CoVER art Political Research Associates always strives to see both the trees and the forest: to go Asad Badat Whether it’s a spree killing, a vandalized mosque, or a beyond caricatures to provide fresh research and analysis on individual conservative bias attack on a queer teen, Americans are quick to chalk it PRInTInG activists and coalitions, but also to situate these actors in the larger infrastructure of Red Sun Press up to hate. The label “hate crime” invites us to blame over- the Right. The first piece in our Summer 2015 issue,“Beyond the Hate Frame” (page wrought individuals acting on extreme personal prejudice, EDIToRIAL BoARD , speaks to this ideal: an interview with Kay Whitlock and Michael Bronski, authors of 3) T.F. Charlton • Frederick Clarkson making it seem as if a small cadre of social deviants is our the new book Considering Hate, which explores how “the hate frame” obscures broader Alex DiBranco • Eric Ethington main obstacle to a peaceful society. In fact, such individu- issues of systemic violence. Kapya Kaoma • L. Cole Parke als are products of a society that endorses all kinds of vio- Tarso Luís Ramos • Spencer Sunshine lence against the very same groups who are targeted in hate As this issue is going to press, the Supreme Court has just announced its historic rul- Mariya Strauss crimes. -

The Real Face of Arabic Symbols

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-17-2017 The Real Face of Arabic Symbols Leena Yahya Sonbuol [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Sonbuol, Leena Yahya, "The Real Face of Arabic Symbols" (2017). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R.I.T The Real Face of Arabic Symbols By Leena Yahya Sonbuol A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Imaging Arts and Sciences School of Art In Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS In Fine Arts Studio Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY Date: May 17, 2017 I Thesis Approval Thesis Title: The Real Face of Arabic Symbols Thesis Author: Leena Yahya Sonbuol Chief Advisor: Eileen Feeney Bushnell (Signature) Date: Associate Advisor: Clifford Wun (Signature) Date: Associate Advisor: Denton Crawford (Signature) Date: Chair, School of Art: Glen Hintz (Signature) Date: II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Eileen Bushnell, and my committee members, Clifford Wun, and Denton Crawford, for the guidance they provide to me while I was working on my thesis. Their doors were always open whenever I ran into a trouble spot or had a question not only regarding my artwork, but also about my life in the USA as an international student. They consistently allowed this paper to be my work but steered me in the right direction whenever they thought I needed it. -

Design Guidelines Manufacturer Guidelines

Congratulations on your participation in the tenth annual Prêt-A-Porter fashion event! Friday May 12th, 7:00 PM EXDO 1399 35th Street Denver, CO 80205 _________________________________________________________________________________________ This document should answer most of your questions about design, materials, and event logistics including: 1. Design Teams 6. Critical Dates 2. Manufacturer Guidelines 7. Model Information 3. Judging Criteria 8. Run-through of the event 4. Prizes 9. Frequently Asked Questions 5. Tickets __________________________________________________________________________________________ ► Design Guidelines Each Design Team will be comprised of up to five members plus a model. We encourage the model to be an integral part of the team and someone with your firm or manufacturer. No hired professional models. The intent of the event is to showcase your manufacturer’s product by using it in a unique and creative way. Look to media coverage of the couture and ready-to-wear fashion shows in New York, Paris, London and Milan for inspiration. Fabrication of the materials into a garment is the responsibility of the design team. We encourage your team to sew and assemble your creation using your own methods. With that said, however, you are allowed to have a seamstress outside of your team help you assemble your garment. This cost would be the responsibility of the design team. However only 10% of the entire garment can be sewn or fabricated by someone outside of your team. ► Manufacturer Guidelines The manufacturer’s only responsibility to the team is to supply the materials for the construction of the garment. The manufacturer is not required to help fabricate the garment; however, with past events, the most successful entries have featured collective collaboration between the design team and the manufacturer and pushed materials to perform in new ways. -

Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011

Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Mary R. Abowd August 2013 © 2013 Mary R. Abowd. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011 by MARY R. ABOWD has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Anne Cooper Professor Emerita of Journalism Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT ABOWD, MARY R., Ph.D., August 2013, Journalism Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011 Director of Dissertation: Anne Cooper This study builds on research that has documented the persistence of negative stereotypes of Arabs and the Arab world in the U.S. media during more than a century. The specific focus is Time magazine’s portrayal of Arabs and their societies between 2001 and 2011, a period that includes the September 11, 2001, attacks; the ensuing U.S.- led “war on terror;” and the mass “Arab Spring” uprisings that spread across the Arab world beginning in late 2010. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study explores whether and to what extent Time’s coverage employs what Said (1978) called Orientalism, a powerful binary between the West and the Orient characterized by a consistent portrayal of the West as superior—rational, ordered, cultured—and the Orient as its opposite—irrational, chaotic, depraved. -

Jailhouse Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim Discrimination in American Prisons

Race Soc Probl (2009) 1:36–44 DOI 10.1007/s12552-009-9003-5 Jailhouse Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim Discrimination in American Prisons Kenneth L. Marcus Published online: 31 March 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 Abstract The post 9/11 surge in America’s Muslim Keywords Islamophobia Á Muslims Á Prisoners’ rights Á prison population has stirred deep-seated fears, including Religious freedom Á Religious discrimination Á the specter that American prisons will become a breeding Religious Land Use and Incarcerated Persons Act system for ‘‘radicalized Islam.’’ With these fears have come restraints on Muslim religious expression. Mistreat- ment of Muslim prisoners violates the Religious Land Use Introduction and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA), which Congress passed in part to protect prisoners from Muslims constitute nearly a tenth of the American federal religious discrimination. Despite RLUIPA, prisoners still prison population and their numbers are rapidly rising.1 face the same challenge that preceded the legislation. The post 9/11 surge in Muslim prison population has stir- Ironically, while Congress directed courts to apply strict red deep-seated fears and resentments, including the scrutiny to these cases, the courts continue to reject most specter that the American prison system will become a claims. One reason is that many courts are applying a breeding system for ‘‘radicalized Islam.’’2 With these fears diluted form of the legal standard. Indeed, the ‘‘war on have come restraints on Muslim religious expression, with terror’’ has justified increasing deference to prison admin- prison officials citing a need to maintain orderly prison istration to the detriment of incarcerated Muslims and administration and ensure homeland security.3 religious freedom. -

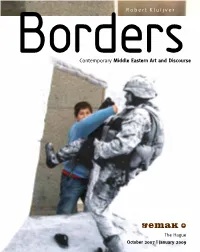

Borders. Contemporary Middle Eastern Art and Discourse

Robert Kluijver BordersContemporary Middle Eastern Art and Discourse The Hague October 2007 | January 2009 Borders Contemporary Middle Eastern Art and Discourse Gemak, The Hague October 2007 to January 2009 Borders Contemporary Middle Eastern Art and Discourse Gemak, The Hague October 2007 to January 2009 Self-published by the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag Print run of 500 copies January 2010 Acknowledgements Most of the support for Gemak came from the municipality of The Hague through the Gemeentemuseum and the Vrije Academie, but essential financial support also came from the Hivos NCDO Cultuurfonds, the Mondriaan Foundation, Kosmopolis Den Haag and Cordaid. I would like to thank these organizations for their willingness to support Gemak in its initial steps. My gratitude to the staff at the Gemeentemuseum (Director Benno Tempel, deputy director Hans Buurman, and Peter Couvee & Annemarie de Jong from the graphic department) who supported this publication. Thanks also to Alan Ingram, Ruchama Marton, Alessandro Petti, Roee Rosen, Tina Sherwell and Eyal Weizman for allowing me to reproduce their texts, either in full or abridged. Credits All texts are by Robert Kluijver except where indicated otherwise. Design by Matthew Adeney. The photographs have either been given by the artists or have been taken by the author, except where attributed otherwise. See photo credits at the back of the book. The points of view expressed herein are the author’s only, and do not reflect those of the Gemeentemuseum, the Vrije Academie or of the artists and writers discussed/quoted. The author takes full responsibility for any eventual mistakes. Note In the period covered by this book Gemak organized more exhibitions than the three that were part of the ‘The Border’ cycle. -

Chinese Propaganda Poster Collection Mss 360

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c85144sw No online items Guide to the Chinese propaganda poster collection Mss 360 Posters processed and described by Sarah Veeck, 2018; finding aid prepared by Sarah Veeck and Zachary Liebhaber, 2018. UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Research Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 93106-9010 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2018 October 10 Guide to the Chinese propaganda poster Mss 360 1 collection Mss 360 Title: Chinese propaganda poster collection Identifier/Call Number: Mss 360 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Research Collections Language of Material: Chinese Physical Description: 8 linear feet(2 map cabinet drawers) Date (inclusive): 1958-1987 Date (bulk): 1970s Abstract: Chinese propaganda posters on a variety of subjects and themes, ranging from the 1950s through the early 1980s. Physical Location: Special Research Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library Language of Material: Poster captions in Chinese. Access Restrictions The collection is open for research. Use Restrictions Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Research Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Research Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Research Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. Acquisition Information Library purchase, 2018. Preferred Citation [Identification of Item], Chinese propaganda poster collection, Mss 360. Department of Special Research Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library, University of California, Santa Barbara. -

Middle East Quick Fact Sheet

Middle East Quick Fact Sheet • The countries that make up the Middle East are: Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, The Palestinian Territories, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. • Iran has the largest population in the region with approximately 70 million people. • Most popular languages spoken: Arabic, Kurdish, Persian, and Hebrew. • Many religions are practice in this region. The most popular are: Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. • When visiting holy sites in the region it is customary to wear a head covering. When visiting Muslim sites modest head covering s are appreciated like a turban, taqiyah (cap) or keffiyeh for males and a scarf for females. Males are required to remove their hats while females wear a keffiyehs or veil when visiting Orthodox Christian sites. For Jewish holy sites males are required to wear a yamulke or any other head wear. • The metric system is used in the Middle East. • Some of the most popular foods in the region are; hummus (a dip made from chickpeas), pita, shawarma (meat wrapped up in pita bread), falafel, baba ghanoush (an eggplant and tahini dip), tabouleh (a salad made with pasley, tomatoes, chick peas and olive oil). It is common to eat from a central platter. • A global warming impact study of the Arabian Gulf by the British University of Dubai predicts that temperatures will rise between 1.8 and 4 degrees Celsius. This will melt ice caps and submerge coastal areas which will force those living in such regions to flee inland. o Reference: http://www.ameinfo.com/148002.html • The United Arab Emirates has the highest carbon footprint on a per capita tonne basis even with its small population. -

A Dangerous, Backbreaking Issue We’Ve Squeezed Two Issues Into One: Lift with Your Legs, Not Your Back! Also in This Issue

THE ENGLISH CHANNEL !SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE: 2011-12 A Dangerous, Backbreaking Issue We’ve squeezed two issues into one: lift with your legs, not your back! Also in this issue retirements, new hirings, changes in More Teaching Excellence leadership, promotions, program Team English honored again! developments, fancy awards, and more. And we’ve jam=packed this issue with as Politics as Sport much information about all of those Laam on the OU hosted GOP debate happenings as time and space would “Unlikely Things” allow. Hoeppner celebrated A few items herein might be a tad on the dusty side, but we promised that Flash Fiction, Ekphrasis nothing has sprouted mold. And there’s Student fiction and poetry even more to report from the semester Kresge Fellowships Awarded Administrate Secretary Cynthia Ferrera; we’ve just !nished up, though we’ve left much of that out until the next issue-- And one goes to Kathy Pfeiffer she’s the greatest which, we promise to our devoted The Cosmopolitans e Channel is back-- and bigger than friends, students, and alumni, will be A book review by Chris Apap ever. After a regrettable, unforeseen hiatus, forthcoming in a much more timely the English department newsletter is at manner than the issue now before you. and that’s not all long last making its triumphant return with At any rate, we’re glad to be back The long and the short on the year’s a massive 30-page issue--and just in time and we’re pretty con!dent you’ll !nd events, faculty awards and publications, for the holidays! this issue worth the wait! A lot has transpired since our last issue-- department and university events, VOLUME 13.2-14.1! 1 THE ENGLISH CHANNEL !SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE: 2011-12 The English Channel The Alumni Newsletter of the Department of English English Dept. -

Risk/Reward: International Short Film Festival Oberhausen | the Brooklyn Rail

7/25/2017 Risk/Reward: International Short Film Festival Oberhausen | The Brooklyn Rail MAILINGLIST Film July 14th, 2017 Risk/Reward: International Short Film Festival Oberhausen by Almudena Escobar López Since its foundation in 1954, the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen has become one of the most established short film festivals in the world. Its famed manifesto, written by several members of the New German Cinema movement in 1962, including Alexander Kluge and Edgar Reitz, set out an agenda for the festival as one devoted to the promotion of artistic freedom and excellence: a festival that is willing to “take any risk” for the sake of new cinema and its future. The founding democratic idea of Oberhausen—“free from control of commercial partners”—is represented through its horizontal approach to programming, which combines both non-curated and curated programs. Although it might seem a great idea on paper, this approach raises a number of questions about the selection and exhibition of the films that sometimes jeopardize the utopic vision of the festival. The non-curated segment of the festival is organized by geographical origin and audience, rather than theme or style: an international section, one German and one from the North Rhine-Westphalia region, a children’s program, and two music video sections. Numbered rather than named, the programs assemble animation, narrative, experimental films, and documentaries all together. As a result, the competition sections are eclectic with a constantly changing flow that is conceptually closer to a television line-up than a film festival. Festival director Lars Henrik Gass advocates a process he calls “compiling” over curating, in which multiple heads work together to create an open dialogue between the films.