4501 200Dpi.Pdf (603.0Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NASCO Rivers Database Report by Jurisdiction

NASCO Rivers Database Report By Jurisdiction Photos courtesy of: Lars Petter Hansen, Peter Hutchinson, Sergey Prusov and Gerald Chaput Printed: 17 Jan 2018 - 16:24 Jurisdiction: Canada Region/Province: Labrador Conservation Requirements (# fish) Catchment Length Flow Latitude Longitude Category Area (km2) (km) (m3/s) Total 1SW MSW Adlatok (Ugjoktok and Adlatok Bay) 550218 604120 W N Not Threatened With Loss 4952 River Adlavik Brook 545235 585811 W U Unknown 73 Aerial Pond Brook 542811 573415 W U Unknown Alexis River 523605 563140 W N Not Threatened With Loss 611 0.4808 Alkami Brook 545853 593401 W U Unknown Barge Bay Brook 514835 561242 W U Unknown Barry Barns Brook 520124 555641 W U Unknown Beaver Brook 544712 594742 W U Unknown Beaver River 534409 605640 W U Unknown 853 Berry Brook 540423 581210 W U Unknown Big Bight Brook 545937 590133 W U Unknown Big Brook 535502 571325 W U Unknown Big Brook (Double Mer) 540820 585508 W U Unknown Big Brook (Michaels River) 544109 574730 W N Not Threatened With Loss 427 Big Island Brook 550454 591205 W U Unknown NASCO Rivers Database Report Page 1 of 247 Jurisdiction: Canada Region/Province: Labrador Conservation Requirements (# fish) Catchment Length Flow Latitude Longitude Category Area (km2) (km) (m3/s) Total 1SW MSW Big River 545014 585613 W N Not Threatened With Loss Big River 533127 593958 W U Unknown Bills Brook 533004 561015 W U Unknown Birchy Narrows Brook (St. Michael's Bay) 524317 560325 W U Unknown Black Bay Brook 514644 562054 W U Unknown Black Bear River 531800 555525 W N Not Threatened -

Planbeskrivelse Rosseland Park

Planbeskrivelse Detaljregulering av Rosseland Park i Kristiansand kommune PlanID 201901 Type: Detaljregulering Saksbehandler: Ellinor Borgi Utarbeidet: Planfolket AS Utgitt: 11.10.2019 – sist revidert: 20.05.2020, 09.09.2020 1 | Side Innholdsfortegnelse Bakgrunn ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Politiske vedtak ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Planavgrensning ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Beskrivelse av dagens situasjon .............................................................................................................. 6 Bebyggelse og grunneierforhold ......................................................................................................... 6 Næringsstrukturer ............................................................................................................................... 7 Naturkvaliteter .................................................................................................................................... 7 Befolkning og eksisterende bebyggelse .............................................................................................. 8 Kulturminner .................................................................................................................................... -

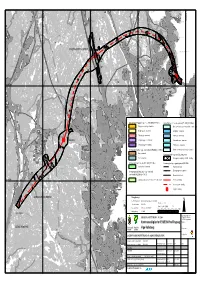

Kommunedelplan for E18/E39 Ytre Ringveg Vige-Volleberg

Stemtjønn Y 434000 Y 437500 Y 441000 Y 444500 StemtjønnStemtjønn SkiftingstjønnSkiftingstjønn Topdalsfjorden Stemtjønn Gillsvann Rauvasstjønn Sandvika Aktjønn Kyrtjønn O Tvitjønn tra L o nn3a m Kutjø 0 t Kutjønna3 jø F n LANGEMYR n Katterumpa MoradstjønnMoradstjønn Bergsvann F v. 18 FAGERHOLT Mumletjønn Slogdalstjønna Grunnevann Stokkebøtjønn Lille Gratjønn 03 Lille Gratjønn F3 Ytre Bergsvann e Stitjønn nnan Lindtjønn Øygardstjønn vitjø Kroktjønn GratjønnGratjønn Fluetjønn re T R Hestnestangen Øv Bjortjønn Svarttjønn Nedre Tvitjønnane v Tigetjønn Lomtjønn Straisvann . SvarttjønnSvarttjønn Straisvann Litjønn Langetjønn 9 BorglitjønnBorglitjønn Grundetjønn Tretjønn Grundetjønn KRISTIANSAND KOMMUNE a F Magnusdalstjønna F v 3 Magnusdalstjønna 1 l 03 TOPDALSFJORDEN e Raudetjønn Øvre Jegersbergvann s Kolåstjønn Bervann l 1 a 6 SØDAL d 4 g F n o Store Geittjønn S Krokevann GIMLEKOLLEN StoreStore Geittjønn Geittjønn JEGERSBERG Songdalselva 3 VOLLEVANN 0 3 Øvre Hellerstøvann F R v . 9 Hestehola LilleLille Geittjønn Geittjønn O T NARVIGA R Nedre Jegersbergvann Børustjønn A Nedre Hellerstøvann Straisvann Hellersvann Kabretjønn Igletjønn 03 F3 Tjuvtjønn F3 BYMARKA F 1 E18 E18 X 6447000 Bånetjønn E18 Anestjønn VIGE HestvannHestvann 3 Hesttjønn 0 3 F Kvislevann 1 7 Nodeland 4 Frydenlund R 303 FrydenlundTjuvtjønn F KJÆRRANE Grotjønn Madsestjønn Svarttjønn F Madsestjønn 2 E18 Nodeland 5 K R a I F lv S O 4 e BANEHEIA ls T F a 6 Nodeland T 1 d KROSSEN R 12 Son g 1 Songdalselva I Hestefallstjønn A LUND A Jentetjønn N Hestetjønn S A R 9 F23 N K O GRIM T -

Horing2014-14364 Uttalelse Fra Fylkesmannen I Vest-Agder, Oppsummering Av Høringsuttalelser.Pdf

Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder Miljøvernavdelingen Saksbehandler: Birgit Solberg Deres ref.: 10.09.2015 Vår dato: 09.10.2015 Tlf.: 38 17 62 12 Vår ref.: 2014/4897 Arkivkode: 443.2 Miljødirektoratet [email protected] Sendes kun som e-post. Regulering av fiske etter anadrome laksefisk i 2016 - Høringsuttalelser Vest-Agder Vedlagt ligger de innkomne høringsinnspillene til forslag til fiskereguleringer. Vi har også lagt ved et sammendrag av høringsinnspillene. Under følger Fylkesmannens kommentarer til de innkomne høringsinspillene. For elvene som ikke har fått innspill i denne høringsrunden viser vi til våre vurderinger i første høringsrunde, som ble sendt inn i mars. Fylkesmannens kommentarer til innkomne forslag: Generelt (uttalelser som går over flere elver) Vest-Agder Grunneier- og Sjølaksefiskelag forslår forbud mot markfiske og mothaker. Fylkesmannen kan ikke se at det er nødvendig med et generelt forbud mot markfiske og mothaker på fiskekrokene. Et slikt forbud bør eventuelt settes der det er påbudt med gjenutsetting, eller der man har spesielle problemer med kroking av fisk og at skadet fisk gjenutsettes. Søgne- og Songdalselva (022.1Z) Søgne- og Songdalselva er en sein elv når det gjelder oppgang av laks, og dagens fiskesesong er for tidlig i forhold til oppgangen. Ukefangstene gjennom sesongen viser at kun 10-20 % av fangsten tas innenfor fisketiden for laks. Gjenutsettingsraten ligger for det meste på over 90 %. Fiskesesongen bør tilpasses slik at det er en reell mulighet til å fiske laks innenfor sesongen. Vi støtter derfor lagets forslag om å få fiske frem til 31.08. Alternativt anbefaler vi at sesongen forskyves med to uker. Fangststatistikken fra de siste 5 årene viser imidlertid at det er liten risiko for at det vil bli tatt fangster av betydning i juni og juli. -

Universitetet I Bergen

ISSN-0801-9576 LABORATORIUM FOR FERSKVANNSØKOLOGI OG INNLANDSFISKE UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN Rapport nr 104/1999 Vannkjemiske og ferskvannsbiologiske undersøkelser i Songdalselva 1998 av Bjørn T. Barlaup, Arne Fjellheim, Sven-Erik Gabrielsen, Einar Kleiven og Øyvind Kaste Etter oppdrag fra Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder Bergen, mars 1999 Rapport nr 104/1999 ISSN-0801-9576 LABORATORIUM FOR FERSKVANNSØKOLOGI OG INNLANDSFISKE (LFI) ZOOLOGISK INSTITUTT TELEFON 55 582236 UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN TELEFAX 55 589674 ALLÉGT 41, 5007 BERGEN RAPPORT–TITTEL: DATO: Vannkjemiske og ferskvannsbiologiske undersøkelser i 22.02.99 Songdalselva, 1998 FEM EMNEORD: FIVE SUBJECT ITEMS: Vannkjemi Water chemistry Forsuring Acidification Kalking/skjellsand Liming/shellsand Sjøaure Seatrout Bunndyr fauna Invertebrate fauna FORFATTERE: GEOGRAFISK OMRÅDE: Bjørn T. Barlaup1, Arne Fjellheim1, Sven Erik Vest-Agder Gabrielsen1, Einar Kleiven2 og Øyvind Kaste2 1) LFI, Bergen 2) NIVA-Sørlandsavd., Televeien 1, 4890 Grimstad OPPDRAGSGIVER: ANTALL SIDER: 46 Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder 2 Forord Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder ba i brev av 21. april 1998 om forslag til statusundersøkelser i Songdalsvassdraget. På grunnlag av et felles forslag til undersøkelsesprogram ble NIVA- Sørlandsavdelingen og LFI, Universitetet i Bergen i brev fra Fylkesmannen 7.mai 1998, bedt om å foreta undersøkelsene. LFI har hatt ansvaret for de biologiske undersøkelser som har omfattet vurdering av fiskebestandene, gjelleprøver og bunndyrsamfunnet. NIVA har hatt ansvaret for de vannkjemiske undersøkelsene og aldersbestemmelsen av fiskematerialet. De kvantitative analysene av aluminium på fiskegjellene er utført ved Laboratorium for Analytisk kjemi (LAK) ved Norges Landbrukshøgskole. De fiskebiologiske undersøkelsene ble utført den 21. april 1998 (gjelleprøver) og i perioden 28-30. september 1998 (ungfiskundersøkelser og gjelleprøver). Innsamlingen av bunndyr ble utført den 3. -

Riverine Inputs and Direct Discharges to Norwegian Coastal Waters – 2015

ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING M-634 | 2016 Riverine inputs and direct discharges to Norwegian coastal waters – 2015 Riverine inputs and direct discharges to Norwegian coastal waters – 2015 | M-634 COLOPHON Executive institution NIVA – Norwegian Institute for Water Research NIVA Report 7098-2016 Project manager for the contractor Contact person in the Norwegian Environment Agency Øyvind Kaste Eivind Farmen M-no Year Pages Contract number 634 2016 86 (210) 16078016 Publisher The project is funded by NIVA Norwegian Environment Agency Author(s) Eva Skarbøvik (NIBIO), Ian Allan (NIVA), Per Stålnacke (NIBIO), Tore Høgåsen (NIVA), Inga Greipsland (NIBIO), John Rune Selvik (NIVA), Liv Bente Schanke (NIVA), Stein Beldring (NVE) Title – Norwegian and English Elvetilførsler og direkte tilførsler til norske kystområder – 2015 ISBN: 978-82-577-6833-1 Riverine Inputs and Direct Discharges to Norwegian Coastal Waters - 2015 Summary – sammendrag Riverine inputs and direct discharges to Norwegian coastal waters in 2015 have been estimated in accordance with the OSPAR Commission’s principles. Nutrients, metals and organic pollutants have been monitored in rivers; discharges from point sources have been estimated from industry, sewage treatment plants and fish farming; and nutrient inputs from diffuse sources have been modelled. Trends in riverine inputs have been analyzed, and threshold concentration levels investigated. Rapporten presenterer resultater fra Elvetilførselsprogrammet i 2015. Næringsstoffer, metaller og organiske miljøgifter er overvåket i norske elver, mens punktutslipp er beregnet fra industri, renseanlegg og akvakultur. Tilførsler av næringsstoff fra diffuse kilder er beregnet ved hjelp av TEOTIL-modellen. Trender i tilførsler fra utvalgte elver er beskrevet. Konsentrasjoner over gitte grenseverdier er funnet for både metaller og organiske miljøgifter i enkelte elver. -

Distribution of Non-Native Brook Trout (Salvelinus Fontinalis) Across Norwegian Waterbodies – Is It an Invasive Species?

Fauna norvegica 2018 Vol. 38: 1-8 Distribution of non-native brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) across Norwegian waterbodies – is it an invasive species? Trygve Hesthagen1, Geir H. Bolstad1 and Einar Kleiven2 Hesthagen T, Bolstad GH and Kleiven E. 2018. Distribution of non-native brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) across Norwegian waterbodies – is it an invasive species? Fauna norvegica 38: 1-8. Non-native brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis MITCHILL, 1815) was introduced into Norway in 1883. However, it was not until the late 1970s that this acid-tolerant salmonid species was stocked into many acidified lakes that many populations became established. In 2004, all brook trout stocking in Norway ceased. In this study, we surveyed the distribution of brook trout in Norwegian water bodies. A totally of 202 self-sustaining populations were identified, mostly in unregulated lakes (n=101), streams (n=71) and also to some extent in reservoirs (n=25). Only four populations were found in inland rivers, and one population in a river with Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Localities with brook trout covered a wide range of altitudes and sizes. Analyses of time-series catches in sympatric populations of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) and brook trout from 12 lakes (1997-2012) revealed a strong decline in brook trout stocks. A similar development in abundance has also emerged from other studies in recent years. Generally, lake-dwelling brook trout is regarded as a low-risk species with respect to invasiveness. However, brook trout/brown trout interactions may be habitat-specific, as brook trout may dominate in small and relatively cold streams. -

(Merknader Til Vedlegg Til § 2 I Forskrift Om Fiske Etter Anadrome Laksefisk I

Vedlegg 2 (Merknader til vedlegg til § 2 i forskrift om fiske etter anadrome laksefisk i vassdrag) Oslo og Viken Glomma (ink Aagaardselva) (002.Z) Nedre Glomma Og På generell basis støtter NGOFA forslaget fra Miljødirektoratet. Omland Fiskeadministrasjon (NGOFA) Sarpsborg og Omegn JFF Foreningen uttalelser seg til bare om reglene for Glomma og Aagaardselva. Når det gjelder Glomma har foreningen ingen merknader til forslaget til nye forskrifter. I Aagaardselva gir foreningen full tilslutning til den foreslåtte forskriften, selv om forslaget fraviker vesentlig fra dagens regler. I dagens forskrift er all hunnlaks over 70 cm fredet hele sesongen. Gytebestandsmålet er oppnådd med god margin, noe som ikke gjenspeiles i dagens regler med hensyn på beskatning. Foreningen støtter derfor forslaget til ny forskrift som åpner for mer beskatning og som samtidig er lettfattelig. I dag er reglene meget omfattende og kompliserte. Spesielt byr det på problemer å overholde påbudet om utsetting av nygått, blank hunnlaks. Hvis det skulle bli behov for innstramming senere er det er mer hensiktsmessig å korte inn fisketida, enn å sette ut hunnlaks i form av catch and release. Miljødirektoratet viser til innkomne merknader. Forslag som ble sendt på høring opprettholdes. Gjersjøelva (005.4Z) Oppegård JFF Foreninga har tidligere spilt inn ønske om fisketid i Gjersjøelva. Foreningen ønsker at fisketida settes fra 15.06 til 30.09. Tidligere var den fra 1.06-30.6 og fra 1.8 til 15.10. De peker på at fiske i oktober vil forstyrre gytingen. Videre påpekes det at forslaget har uteglemt fisketid for laks i Gjersjøelva. I dag er det tillatt å fiske laks innenfor fisketida for sjøørret. -

Tiltaksprogram Mandal-Audna Vannområde

Sammen for vannet Tiltaksprogram i vannområde Mandal - Audna Foto: Vegard Næss Innhold 1. Innledning ............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Om tiltaksprogrammet ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1. Vannområdet vårt ......................................................................................................................... 4 3. Miljøtilstand og miljøutfordringer ....................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Økologisk og kjemisk tilstand til vannforekomster i vannområdet ............................................... 7 3.2 Hovedutfordringer i vannområdet ................................................................................................. 8 4. Forslag til tiltak innenfor kommunalt ansvarsområde ....................................................................... 10 4.1 Avløpsvann ................................................................................................................................. 11 4.2 Landbruk ..................................................................................................................................... 16 4.3 Beskyttelse av drikkevann .......................................................................................................... 18 4.4 Klimatilpasning .......................................................................................................................... -

KDP1406-1.Pdf

Stemtjønn Y 434000 Y 437500 Y 441000 Y 444500 StemtjønnStemtjønn SkiftingstjønnSkiftingstjønn Topdalsfjorden Stemtjønn Ruiner Gillsvann Rypestøl Rauvasstjønn Sandvika Aktjønn Kyrtjønn O Tvitjønn tra L o nn3 a Øvre Blokkedal m Ruiner Kutjø 0 t Kutjønna3 jø F n LANGEMYR n Katterumpa MoradstjønnMoradstjønn Bergstølhytta Bergsvann Bergstølhytta F v. 18 FAGERHOLT Mumletjønn Slogdalstjønna Grunnevann Nedre Blokkedal Idrettsplass Stokkebøtjønn 3 LilleLille GratjønnGratjønn F30 Travbane Ytre Bergsvann e Stitjønn nnan Lindtjønn Øygardstjønn vitjø Kroktjønn Gratjønn Fluetjønn e T R Hestnestangen Gratjønn Øvr Bjortjønn S Nedre Tvitjønnane Svarttjønn o Lomtjønn v n Tigetjønn g Straisvann . Svarttjønn d Straisvann Litjønn Langetjønn 9 Lekeplass Svarttjønn a le n BorglitjønnBorglitjønn Trafo Grundetjønn Tretjønn Grundetjønn KRISTIANSAND KOMMUNE a F Magnusdalstjønna F v 3 Magnusdalstjønna 1 l 03 TOPDALSFJORDEN e Raudetjønn Øvre Jegersbergvann s Kolåstjønn Bervann l 1 a 6 SØDAL d 4 g F n o Store Geittjønn S Krokevann GIMLEKOLLEN StoreStore Geittjønn Geittjønn JEGERSBERG Songdalselva 3 VOLLEVANN 0 3 Øvre Hellerstøvann R F S v o . 9 Hestehola Lille Geittjønn n Lille Geittjønn g O NARVIGA d T Børustjønn a R Nedre Jegersbergvann le A n Nedre Hellerstøvann Straisvann Hellersvann Kabretjønn Igletjønn 03 F3 Tjuvtjønn F3 BYMARKA F 1 E18 E18 X 6447000 Bånetjønn E18 Anestjønn VIGE HestvannHestvann 3 n 0 Hesttjønn e 3 F mm Kvislevann e 1 t 7 s e Nodeland n k 4 k Frydenlund n R 03 FrydenlundTjuvtjønn jø a F3 t b o i Grotjønn r k KJÆRRANE G s Svarttjønn F Madsestjønn -

Behandling Av Høringsuttalelser

Saksframstilling Sykkelhandlingsplan for Kristiansandsregionen 2011-2020: Behandling av høringsuttalelser. Høringsforslaget til sykkelhandlingsplan for Kristiansandsregionen 2011-2020 har vært på høring i ATP-kommunene og andre berørte instanser/organisasjoner. En sammenfatninga av høringsuttalelsene samt ATP-sekretariatets behandling av disse. Planforslaget har i hovedsak fått tilslutning, men ATP- sekretariatet foreslår å justere planen på en del punkter på grunnlag av høringsuttalelsene. ATP-sekretariatets egne endringer finnes i slutten av dokumentet. Det har kommet høringsinnspill fra følgende kommuner/fylkeskommuner: Vennesla kommune: Bygg- og miljøutvalget og Kommunestyret Søgne kommune: Formannskapet og Kommunestyret Kristiansand kommune: Byutviklingsstyret og Formannskapet Songdalen kommune: Planutvalget, og Kommunestyret Lillesand kommune: Formannskapet og Bystyret Birkenes kommune: Kommunestyret I tillegg har det kommet høringsinnspill fra følgende instanser/organisasjoner: Vennesla kommune: Råd for funksjonshemmede og Eldrerådet Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder: Miljøvernavdelingen Folkehelseforum Kristiansand: Arbeidsutvalget og Folkehelseforum Midt-Agder friluftsråd Norsk Zoologisk Forening, Sørlandsavdelingen, Norsk Ornitologisk Forening, Kristiansand lokallag og Agder Botaniske Forening (samlet uttalelse) Fagpersoner ved UiA Agder naturmuseum og botaniske hage Naturvernforbundet i Søgne Naturvernforbundet i Kristiansand FAU Havlimyra skole, FAU Justvik og Erkleiv skole, Justvik velforening Ålefjær vel Justvik Vel Søgne kommunale -

Biologiske Undersøkelser I Kalkede Vann I Vest-Agder 2008, Med Vekt På Krepsdyr, Bunndyr Og Fisk

450 Biologiske undersøkelser i kalkede vann i Vest-Agder 2008, med vekt på krepsdyr, bunndyr og fisk Gunnar Halvorsen Trygve Hesthagen Dag Svalastog Terje Bongard NINAs publikasjoner NINA Rapport Dette er en ny, elektronisk serie fra 2005 som erstatter de tidligere seriene NINA Fagrapport, NINA Oppdragsmelding og NINA Project Report. Normalt er dette NINAs rapportering til oppdragsgiver etter gjennomført forsknings-, overvåkings- eller utredningsarbeid. I tillegg vil serien favne mye av instituttets øvrige rapportering, for eksempel fra seminarer og konferanser, resultater av eget forsk- nings- og utredningsarbeid og litteraturstudier. NINA Rapport kan også utgis på annet språk når det er hensiktsmessig. NINA Temahefte Som navnet angir behandler temaheftene spesielle emner. Heftene utarbeides etter behov og seri- en favner svært vidt; fra systematiske bestemmelsesnøkler til informasjon om viktige problemstil- linger i samfunnet. NINA Temahefte gis vanligvis en populærvitenskapelig form med mer vekt på illustrasjoner enn NINA Rapport. NINA Fakta Faktaarkene har som mål å gjøre NINAs forskningsresultater raskt og enkelt tilgjengelig for et større publikum. De sendes til presse, ideelle organisasjoner, naturforvaltningen på ulike nivå, politikere og andre spesielt interesserte. Faktaarkene gir en kort framstilling av noen av våre viktigste forsk- ningstema. Annen publisering I tillegg til rapporteringen i NINAs egne serier publiserer instituttets ansatte en stor del av sine vi- tenskapelige resultater i internasjonale journaler, populærfaglige bøker og tidsskrifter. Norsk institutt for naturforskning Biologiske undersøkelser i kalkede vann i Vest-Agder 2008, med vekt på krepsdyr, bunndyr og fisk Gunnar Halvorsen Trygve Hesthagen Dag Svalastog Terje Bongard NINA Rapport 450 Halvorsen, G , Hesthagen, T., Svalastog, D., & Bongard, T. 2009. Bio- logiske undersøkelser i kalkede vann i Vest-Agder 2008, med vekt på krepsdyr, bunndyr og fisk.