Pakistan's Fight Against Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU)

Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) Brief Number 6 The 2007 Elections and the Future of Democracy in Pakistan Lt. Gen. Talat Masood [Rted] 1st March 2007 About the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) The Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) was established in the Department of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, UK, in March 2007. It serves as an independent portal and neutral platform for interdisciplinary research on all aspects of Pakistani security, dealing with Pakistan's impact on regional and global security, internal security issues within Pakistan, and the interplay of the two. PSRU provides information about, and critical analysis of, Pakistani security with particular emphasis on extremism/terrorism, nuclear weapons issues, and the internal stability and cohesion of the state. PSRU is intended as a resource for anyone interested in the security of Pakistan and provides: • Briefing papers; • Reports; • Datasets; • Consultancy; • Academic, institutional and media links; • An open space for those working for positive change in Pakistan and for those currently without a voice. PSRU welcomes collaboration from individuals, groups and organisations, which share our broad objectives. Please contact us at [email protected] We welcome you to look at the website available through: http://spaces.brad.ac.uk:8080/display/ssispsru/Home Other PSRU Publications The following papers are freely available through the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) • Brief number 1. Pakistan, Biological Weapons and the BTWC • Brief number 2. Sectarianism in Pakistan • Brief number 3. Pakistan, the Taliban and Dadullah • Brief number 4. Security research in Pakistan • Brief number 5. Al-Qaeda in Pakistan • Brief number 6. -

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, editors Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. ISBN 0-9747255-8-7 The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street NW Twelfth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... vii Introduction......................................................................................................... ix 1. The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia Michael Krepon ............................................................................................ 1 2. Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia: Structural Factors Rodney W. Jones......................................................................................... 25 3. India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture Rajesh M. Basrur ........................................................................................ 56 4. Nuclear Signaling, Missiles, and Escalation Control in South Asia Feroz Hassan Khan ................................................................................... -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

Colonel (GS) Hans Eberhart∗

Pakistan’s Need forIPRI a Comprehensiv Journal XI, no.e Politico-Strategic 2 (Summer 2011): Reorientation 1-43 1 IN THE INTEREST OF ITS PEOPLE: PAKISTAN’S NEED FOR A COMPREHENSIVE POLITICO-STRATEGIC REORIENTATION - OBSERVATIONS FROM AN EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE Colonel (GS) Hans Eberhart∗ Abstract Pakistan is once more at a crossroads. It faces a set of interlocked problems, an unprecedented existential challenge related to comprehensive security (politico-social, military and economic dimensions; and not only to its physical security). The reasons for this grim state of national affairs are diverse, but cumulating and interlinked, for which partially Pakistan itself but also external actors are responsible. In order to tackle the problems Pakistan will need a new thinking and approach – primarily helping itself. This concretely means: changing the society through mobilisation of the human and resource- oriented potentials existing in the country (source of inspiration through “asabiyya”), supporting the youth and training “ideal leaders”, working for a “just power Nation”, and forming a national consensus for the implementation of a comprehensive set of reforms which has to provide stability and peace. Critical factors to be taken into account for this will be the perceptions and interests of the people, a shift from the national-military to the human dimension of security, and, above all, the respect of the will of Pakistan’s people for self-determination and sovereignty by external actors as well as honest and reliable relations conducted -

Pakistan S Long Tradition of Military Rule II: Musharraf S Follies and the Present Scenario, By

Pakistan’s Long Tradition of Military Rule–II*: Musharraf’s Follies and the Present Scenario Gurmeet Kanwal Military Disaster The Pakistan Army’s military defeat on the Line of Control (LoC) at Kargil in the summer months of 1999 and its ignominious withdrawal from the few remaining areas under its occupation came as a traumatic shock for the nation that had been conditioned to believe that the Pakistan Army-Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) combine had reduced the Indian Army to a demoralised force over ten years of proxy war and that the so-called Mujahideen (actually a motley array of rag- tag mercenary terrorists grouped into several jihadi outfits), were invincible. Hallucinatory public announcements of non-existent victories made the ultimate defeat much harder to accept. The people of Pakistan were even more disillusioned when the truth gradually dawned that the intruders were mainly troops of the regular Northern Light Infantry (NLI) battalions of the Pakistan Army and that the official line that they were Kashmiri freedom fighters was a skillfully crafted charade.1 Besides captured Pakistani small arms, crew-served weapons and ammunition with Pakistan Ordnance Factories markings on them, India produced hard documentary evidence of the presence of regular Pakistan soldiers – identity cards, army pay books, operational orders, medal ribbons, NLI shoulder titles and other uniform insignia, daily parade state books of sundry Brigadier Gurmeet Kanwal (Retd) is Director, Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. * Part-I was published in CLAWS Journal, Winter 2008. CLAWS Journal l Winter 2009 67 GURMEET KANWAL havildar (sergeant) majors, ration issue receipts and letters and photographs from family members. -

The Future of Pakistan

FOREIGN POLICY at Brookings The Future of Pakistan Stephen P. Cohen South Asia Initiative THE FUTURE OF PAKISTAN Stephen P. Cohen The Brookings Institution Washington, D.C. January 2011 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Stephen P. Cohen is a senior fellow in Foreign Policy at Brookings. He came to Brookings in 1998 after a long career as professor of political science and history at the University of Illinois. Dr. Cohen previously served as scholar-in-residence at the Ford Foundation in New Delhi and as a member of the Policy Planning Staff of the U.S. State Department. He has also taught at universities in India, Japan and Singapore. He is currently a member of the National Academy of Science’s Committee on International Security and Arms Control. Dr. Cohen is the author or editor of more than eleven books, focusing primarily on South Asian security issues. His most recent book, Arming without Aiming: India modernizes its Military (co- authored with Sunil Das Gupta, 2010), focuses on India’s military expansion. Dr. Cohen received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at the University of Chicago, and a PhD from the University of Wisconsin. EDITOR’S NOTE This essay and accompanying papers are also available at http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2010/09_bellagio_conference_papers.aspx 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE………………………………………………………………………….. 1 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….3 PAKISTAN TO 2011………………………………………………………………. 5 FOUR CLUSTERS I: Demography, Education, Class, and Economics………………………….. 16 II: Pakistan’s Identity……………………………………………………….. 23 III: State Coherence………………………………………………………… 27 IV: External and Global Factors…………………………………………...... 34 SCENARIOS AND OUTCOMES…………………………………………………. 43 CONCLUSIONS…………………………………………………………………… 50 SIX WARNING SIGNS……………………………………………………………. 51 POLICY: BETWEEN HOPE AND DESPAIR……………………………………. -

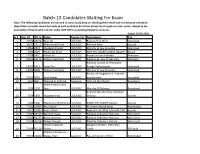

Batch-15 Candidates Waiting for Exam

Batch-15 Candidates Waiting For Exam Note: The following Candidates are advised to consciously keep on checking their email and sms because intimation about Exam schedule would be made to each candidate by Virtual University through sms and email, subject to the availability of Examination Center under GOP SOP in prevailing Pandemic scenario. Dated: 10-03-2021 Sr # App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For Department City 1 75542 23163 Noor Ali LDC/UDC Regional Tax Office Islamabad 2 39077 22111 Muhammad Tariq LDC/UDC Pakistan Navy Karachi 3 12855 2822 Muqbool Ahmed LDC/UDC Ministry of Law & Justice Islamabad 4 4995 1025 MAJID ALI KHAN LDC/UDC AMF PAC BOARD KAMRA (MoDP) Attock 5 19298 5431 Adnan Ali LDC/UDC Postal Services Pakistan Peshawar 6 29039 10173 Muhammad hanif LDC/UDC Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Peshawar Pakistan Council of Renewable 7 18155 5413 Sadar Din LDC/UDC Energy Technologies Islamabad 8 13701 4000 Muhammad Islam LDC/UDC Ministry of Law & Justice, Islamabad Bureau of emigration & overseas 9 25935 8315 Saad Nawaz LDC/UDC employment islamabad 10 4537 992 Muneeb ur Rehman Assistant GHQ, PS Directorate Rawalpindi Muhammad Junaid 11 2296 1174 Ilyas LDC/UDC Ministry Of Defence Rawalpindi Airports Security Force /Aviation 12 5876 1403 Muzaffar Khan LDC/UDC Division Karachi 13 2933 1000 Mahmood UR Rehman LDC/UDC PNMIT DTE KS&EW Karachi Karachi 14 74369 22085 Nasir Bashir LDC/UDC FF Centre Record Wing Abbottabad 15 70352 22086 Yusra Sohail LDC/UDC Regional Tax Office-I,Karachi, FBR Karachi. 16 71005 20526 Zahid Ali Awan Assistant Pakistan Ordnance Factories Wah Cantt 17 71010 20527 Aamir Waheed LDC/UDC Pakistan Ordnance Factories Wah Cantt 18 71014 20528 Nabeel Ahmad LDC/UDC Pakistan Ordnance Factory Wah Cantt Muhammad Zain Weapons Factory, POFs Wah 19 71306 20529 Shahid LDC/UDC Cantt. -

Cover Page – Title

KASHMIR: THE VIEW FROM ISLAMABAD 4 December 2003 ICG Asia Report N°68 Islamabad/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. HISTORY OF THE KASHMIR CONFLICT – A PAKISTANI PERSPECTIVE 3 III. PERCEPTIONS OF NATIONAL SECURITY ........................................................... 4 A. HISTORY OF WAR .................................................................................................................4 B. SIMLA AGREEMENT ..............................................................................................................5 C. KASHMIRI MILITANCY, PAKISTANI INTERVENTION AND NEAR WAR CRISES.........................5 D. COSTS OF CONFLICT .............................................................................................................8 IV. DOMESTIC OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS......................................... 10 A. CIVIL AND MILITARY BUREAUCRACIES ..............................................................................10 B. REGIONAL DIFFERENCES.....................................................................................................15 C. POLITICAL PARTIES.............................................................................................................16 1. Regional Parties .......................................................................................................17 -

Special Warfare

January - March 2014 | Volume 27 | Issue 1 On the Cover Special Operations in the U.S. Pacifc Command Area of Responsibility Cover and Left: A Philippine Army Special Forces Soldier teaches a jungle survival training course to fellow Philippine Special Forces and a Special Forces Operational Detach- ment - Alpha. U.S. Army photo. ARTICLES DEpaRTMENTS 08 1st Special Forces Group in the PACOM AOR 04 From the Commandant 16 Q&A with COL Robert McDowell and CSM Brian Johnson 05 Updates 21 1st Special Forces Group Support Battalion 07 Training Updates 26 Relationship Building 71 Career Notes 30 1st SFG(A) Operational Cycle 74 Fitness 34 The Case for India 38 Zamboanga Crisis 75 Book Review 46 Operation Enduring Freedom - Philippines 52 Operation Damayan 59 Preparing for ODA Level Initial Entry UW Operations in Korea 62 Foal Eagle 66 A Company In the LSF 68 UW in Cyberspace Special Warfare U.S. ARMY JOHN F. KENNEDY Commander & Commandant SPECIAL WARfaRE CENTER AND SCHOOL Brigadier General David G. Fox MISSION: The U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, the U.S. Army’s Special Operations Center of Excellence, trains, Chief, Strategic Communication educates, devleops and manages world-class Civil Affairs, Psychological Lieutenant Colonel April Olsen Operations and Special Forces warriors and leaders in order to provide the Army special operations forces regiments with professionally trained, highly educated, innovative and adaptive operators. Editor Janice Burton VISION: Professionalism starts here. We are an adaptive institution characterized by agility, collaboration, accountability and integrity. We promote life-long learning and transformation. -

Explaining the Resilience of the Balochistan Insurgency

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Spring 2019 Explaining the Resilience of the Balochistan Insurgency Tiffany Tanner University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Tanner, Tiffany, "Explaining the Resilience of the Balochistan Insurgency" (2019). Honors College. 533. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/533 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLAINING THE RESILIENCE OF THE BALOCHISTAN INSURGENCY by Tiffany Tanner A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (International Affairs) The Honors College University of Maine May 2019 Advisory Committee: Asif Nawaz, Assistant Professor of History and International Affairs, Advisor Paul Holman, Adjunct Professor of Political Science Hao Hong, Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Preceptor in the Honors College James Settele, Executive Director of the School of Policy & International Affairs Kristin Vekasi, Assistant Professor of Political Science ABSTRACT The Balochistan Insurgency is an enduring armed and nationalist struggle between Baloch Insurgents and the Pakistani government, embroiling Pakistan in five insurgencies since 1948. This research aims to analyze why the current insurgency has outlasted its predecessors by over two-fold, with over fifteen years passing since the most recent conflict erupted. Using historical primary source news articles from 1973-1977, secondary research, insurgency trend data, and the data from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD); this study examines the evolution of the current conflict and analyzes how and why the contemporary insurgency is far more resilient. -

Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU)

Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) Brief Number 21 Pakistan’s Political Situation Talat Masood 9th of October 2007 About the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) The Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) was established in the Department of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, UK, in March 2007. It serves as an independent portal and neutral platform for interdisciplinary research on all aspects of Pakistani security, dealing with Pakistan's impact on regional and global security, internal security issues within Pakistan, and the interplay of the two. PSRU provides information about, and critical analysis of, Pakistani security with particular emphasis on extremism/terrorism, nuclear weapons issues, and the internal stability and cohesion of the state. PSRU is intended as a resource for anyone interested in the security of Pakistan and provides: • Briefing papers; • Reports; • Datasets; • Consultancy; • Academic, institutional and media links; • An open space for those working for positive change in Pakistan and for those currently without a voice. PSRU welcomes collaboration from individuals, groups and organisations, which share our broad objectives. Please contact us at [email protected] We welcome you to look at the website available through: http://spaces.brad.ac.uk:8080/display/ssispsru/Home Other PSRU Publications The following papers are freely available through the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) • Brief number 10. Towards a Durable Peace in Waziristan • Brief number 11. An Uncertain Voice: the MQM in Pakistan's Political Scene • Brief number 12. Lashkar-e-Tayyeba • Brief number 13. Pakistan – The Threat From Within • Brief number 14. Is the Crescent Waxing Eastwards? • Brief number 15.