Przekładaniec, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Updated: 20 January 2012 1 42.347 Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline Film

1 42.347 Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline Film Review Essay Assignment Holocaust Films: “Imagining the Unimaginable” The average American's most extensive exposure to the Holocaust is through popular filmic presentations on either the "big screen" or television. These forums, as Ilan Avisar points out, must yield “to popular demands and conventional taste to assure commercial success."1 Subsequently, nearing the successful completion of this course means that you know more about the Holocaust than the average American. This assignment encourages you to think critically, given your broadened knowledge base, about how the movie-television industry has treated the subject. Film scholars have grappled with the unique challenge of Holocaust-themed films. Ponder their views as you formulate your own opinions about the films that you select to watch. Annette Insdorff, Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust (1989) "How great a role are films playing in determining contemporary awareness of the Final Solution? . How do you show people being butchered? How much emotion is too much? How will viewers respond to light-hearted moments in the midst of suffering?" (xviii) How do we lead a camera or a pen to penetrate history and create art, as opposed to merely recording events? What are the formal as well as moral responsibilities if we are to understand and communicate the complexities of the Holocaust through its filmic representations? (xv) Ilan Avisar, Screening the Holocaust: Cinema's Images of the Unimaginable (1988) "'Art [including film making] takes the sting out of suffering.'" (viii) The need for popular reception of a film inevitably leads to "melodramatization or trivialization of the subject." (46) Hollywood/American filmmakers' "universalization [using the Holocaust to make statements about contemporary problems] is rooted in specific social concerns that seek to avoid burdening a basically indifferent public with unbearable facts of the Nazi genocide of the Jews. -

September / October

AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 46-No. 1 ISSN 0892-1571 September/October 2019-Tishri/Cheshvan 5780 “TWO ARE BETTER THAN ONE… AND A THREEFOLD CORD CANNOT QUICKLY BE BROKEN” n Sunday, November 17, 2019, the are leaders of numerous organizations, including membrance for their grandparents, and to rein- American Society for Yad Vashem AIPAC, WIZO, UJA, and American Friends of force their commitment to Yad Vashem so that will be honoring three generations of Rambam Hospital. the world will never forget. Oone family at our Annual Tribute Din- Jonathan and Sam Friedman have been ll three generations, including ner in New York City. The Gora-Sterling-Fried- deeply influenced by Mona, David and their ex- David’s three children — Ian and his man family reflects the theme of this year’s traordinary grandparents, Jack and Paula. Grow- wife Laura, Jeremy and his wife Tribute Dinner, which comes from Kohelet. “Two ing up, they both heard Jack tell his story of AMorgan, and Melissa — live in the are better than one… and a threefold cord can- survival and resilience at the Yom HaShoah pro- greater New York City area. They gather often, not quickly be broken” (4:9-12). All three gener- ations are proud supporters of Yad Vashem and are deeply committed to the mission of Holo- caust remembrance and education. Paula and Jack Gora will receive the ASYV Remembrance Award, Mona and David Sterling will receive the ASYV Achievement Award, and Samantha and Jonathan Friedman and Paz and Sam Friedman will receive the ASYV Young Leadership Award. -

SON 509 S. X-XXV Neu SON

SON 509_S.XXVI-XL_neu_SON 509 18.02.2015 08:24 Seite XXVI XXVI Introduction Hanns Eisler composed the film music for Nuit et brouillard – d’Ulm in Paris. On 10 November 1954, the day the exhibition “Night and fog” – in the few weeks between late November opened, its two curators – the historians Olga Wormser and and mid-December 1955. Nuit et brouillard was the first com- Henri Michel – mentioned in a radio interview4 that they were prehensive documentary film about the Nazi concentration planning a film about the concentration camp system. camps.1 It was directed by Alain Resnais and the commentary According to Wormser, it would “only contain purely histori- was by the writer Jean Cayrol, who had himself been a prisoner cal documents that are absolutely confirmed by all our experi- in the concentration camp of Mauthausen/Gusen. This short ence with this subject”.5 Wormser and Michel had been film Nuit et brouillard is underlaid throughout its 30 minutes researching the topic of deportation and concentration camps by both Eisler’s music and the commentary, which was spoken for several years. In 1940–41, Wormser had worked in the by the actor Michel Bouquet. The title of the film refers to the Centre d’information sur les prisonniers de guerre (“Centre of “order of the Führer” of the same name from 1941, according information on prisoners of war”) and in September 1944 had to which the Resistance fighters captured in France, Belgium, been employed in the Commissariat aux Prisonniers, Déportés the Netherlands and Norway were placed under the special et Réfugiés (“Commissariat for prisoners, deportees and jurisdiction of the “Reich” in order for them to disappear refugees”, PDR) of the provisional government of the French without trace in prisons and concentration camps in a “cloak Republic under Minister Henri Frenay – this was the board and dagger” operation (in German: “bei Nacht und Nebel”, concerned with registering, returning and resettling deported literally “in night and fog”).2 people and POWS. -

Cultural Response to Totalitarianism in Select Movies Produced in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland Between 1956 and 1989 Kazimierz Robak University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Cultural response to totalitarianism in select movies produced in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland between 1956 and 1989 Kazimierz Robak University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Robak, Kazimierz, "Cultural response to totalitarianism in select movies produced in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland between 1956 and 1989" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2167 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Response to Totalitarianism in Select Movies Produced in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland between 1956 and 1989 by Kazimierz Robak A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Silvio Gaggi, Ph.D. Adriana Novoa, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 6, 2009 Keywords: bolshevism, communism, communist propaganda, sovietism, film, peter bacso, milos forman, jan nemec, istvan szabo, bela tarrr, andrzej wajda, janusz zaorski © Copyright 2009, Kazimierz Robak Dedication To my wife Grażyna Walczak, my best friend, companion and love and to Olga, a wonderful daughter Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Maria Cizmic, who has been an extraordinary advisor in the best tradition of this institution. -

Print This Article

Tryuk, M. (2016). Interpreting and translating in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series: Themes in Translation Studies, 15, 121–141. Interpreting and translating in Nazi concentration camps during World War II Małgorzata Tryuk University of Warsaw, Poland [email protected] This article investigates translation and interpreting in a conflict situation with reference to the Nazi concentration camps during World War II. In particular, it examines the need for such services and the duties and the tasks the translators and the interpreters were forced to execute. It is based on archival material, in particular the recollections and the statements of former inmates collected in the archives of concentration camps. The ontological narratives are compared with the cinematic figure of Marta Weiss, a camp interpreter, as presented in the docudrama “Ostatni Etap” (“The last Stage”) of 1948 by the Polish director Wanda Jakubowska, herself a former prisoner of the concentration camp. The article contributes to the discussion on the role that translators and interpreters play in extreme and violent situations when the ethics of interpreting and translation loses its power and the generally accepted norms and standards are no longer applicable. 1. Introduction Studies on the roles of translators and interpreters in conflict situations have been undertaken by numerous scholars since 1980. They have produced valuable insights into the subject which include various types of study of an empirical, analytical -

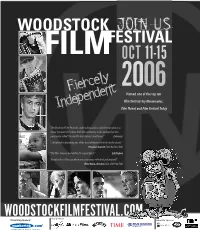

Wff Freeman Insert

JOIN US OCT 11-15 llyy 2006 FFiieerrccee nnddeenntt Named one of the top ten ddeeppee film festivals by Moviemaker, IInn Film Threat and Film Festival Today “The Woodstock Film Festival is quite a draw,and its solid line-up attracts a broad spectrum of the New York film community to the enclave that one participant called “the world’s most famous small town.” (Indiewire) “...Woodstock is becoming one of the most distinctive festivals on the circuit.” (Stephen Garrett,Time Out New York) “The films here are wonderful,it’s a great place.” (Lili Taylor) “Woodstock is a film spa where you come away refreshed and inspired!” (Ron Mann, director, Tales of the Rat Fink) ©R WOODSTOCKFILMFESTIVAL.COM oth 2006 Key Sponsors: Presenting Sponsor: Superstar Sponsor: ABOUT WOODSTOCK FILM FESTIVAL The Woodstock Film Festival As a not-for-profit, 501(c)(3) organization, our mission is to present an annual program and celebrates new and established year-round schedule of film, music and art-related activities that promote artists, culture and inspires learning and diversity. The Hudson Valley Film Commission promotes sustainable voices in independent film with economic development by attracting and supporting film, video and media production. screenings, seminars, workshops Every fall, film and music lovers from around the world gather here for an exhilarating variety of films, concerts, celebrity-led seminars, workshops, an awards ceremony and and concerts throughout the mid- superlative parties. Visitors find themselves in a relaxed, receptive atmosphere surrounded by Hudson Valley. some of the most beautiful landscapes in the world. More than 125 films are screening, including feature films, documentaries and shorts, many of which are premieres from the U.S. -

Perth / 18 F Eb — 3 Mar Brisbane / 18

Program Festival 2021 Melbourne / 17 Feb — 16 Mar Sydney / 18 Feb — 24 Mar Brisbane / 18 — 28 Feb, Canberra / 17 — 28 Feb 28 — 17 / Canberra Feb, 28 — 18 / Brisbane Mar 3 — Feb 18 / Perth SPONSORS, PARTNERS & FRIENDS OF JIFF — CHAI SPONSORS — SILVER SPONSORS — BRONZE SPONSORS — Sponsorship & advertising enquiries [email protected] 2 COVER Top: When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (pg 45); Bottom: Persian Lessons (pg 34). SPONSORS, PARTNERS & FRIENDS OF JIFF — MEDIA PARTNERS — CULTURAL & PROGRAMMING PARTNERS — FRIENDS OF JIFF — Abraham Australian Migration Lauren and Bruce Fink Anonymous Milne Agrigroup Anonymous NEXA A.I.S. Insurance Noah’s Creative Juices Arnold Bloch Leibler The Pacific Group Peter Berkowitz Project Accounting Australia Connect Plus Property Solutions PSN Family Charitable Trust Escala Partners Rampersand Fraid Family See-Saw Films Ian Sharp Jewellery Shadowlane Jackie Vidor & Phil Staub Viv and Phil Green 3 The 2021 Jewish International Film Festival CONTENTS — Highlight Events . 6 Films (alphabetical order). 8 Melbourne Schedule ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������46 Melbourne Events . 50 Sydney Schedule . 52 Sydney Events ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������54 Perth, Brisbane and Canberra Schedules. 55 Tickets & Venue Info. 64 Booking Form . 65 Index ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������67 -

Presentation for the US Holocaust Memorial Museum

The Mother of all Holocaust Films? Wanda Jakubowska’s Auschwitz trilogy by Hanno Loewy “We must first speak about the genre of this wonderful Polish film.”1 With these words in 1948 Béla Balázs, one of the first and most influential film-theorists of all times, began his discussion of Wanda Jakubowska’s Ostatni Etap (The Last Stop / The Last Stage), the first feature film, that made the attempt to represent the horrors of Auschwitz, the experiences, made in midst of the universe of mass extermination. Filmed during summer 1947 on the site of the camp itself and its still existing structures, directed and written by two former prisoners of the women’s camp in Birkenau, performed not only by actors but also by extras, who had suffered in the camp themselves, Jakubowska’s film acquired soon the status of a document in itself. [illustration #1] Béla Balázs did not only praise The Last Stop for its dramatic merits. He discussed the failure, the inadequacies of traditional genres to embody what happened in the camps. Himself a romantic Communist, but also a self-conscious Jew, he spent half of his life in exile, in Vienna, Berlin and Moscow. And in the end of 1948 he was about to leave Hungary for a second time, now deliberately, to become dramaturgic advisor of the DEFA in East Berlin. But that never happened. Just having settled his contract, he died in Budapest, in May 1949. In 1948 Béla Balázs is far away from any conceptualizing of the Shoah as a paradigm, but he senses something uneasy about the idea of having represented these events as a classical tragedy, or a comedy, or a novel. -

Holocaust Film Before the Holocaust

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 22:42 Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Holocaust Film before the Holocaust: DEFA, Antifascism and the Camps Les films sur l’Holocauste avant l’Holocauste : la DEFA, l’antifascisme et les camps David Bathrick Mémoires de l’Allemagne divisée. Autour de la DEFA Résumé de l'article Volume 18, numéro 1, automne 2007 Très peu de films représentant l’Holocauste ont été produits avant les années 1970. Cette période a souvent été considérée, sur le plan international, comme URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/017849ar une période de désaveu, tant politique que cinématographique, de la DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/017849ar catastrophe ayant frappé les Juifs. Outre les productions hollywoodiennes The Diary of Anne Frank (George Stevens, 1960), Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Aller au sommaire du numéro Kramer, 1961) et The Pawnbroker (Sidney Lumet, 1965), on a souvent fait remarquer que peu de films est- ou ouest-européens ont émergé de ce paysage politique et culturel, ce qui a été perçu par plusieurs comme une incapacité ou une réticence à traiter du sujet. Le présent article fait de cette présomption son Éditeur(s) principal enjeu en s’intéressant à des films tournés par la DEFA entre 1946 Cinémas et 1963, dans la zone soviétique de Berlin-Est et en Allemagne de l’Est, et qui ont pour objet la persécution des Juifs sous le Troisième Reich. ISSN 1181-6945 (imprimé) 1705-6500 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Bathrick, D. (2007). Holocaust Film before the Holocaust: DEFA, Antifascism and the Camps. -

Auschwitz Concentration Camp 1 Auschwitz Concentration Camp

Auschwitz concentration camp 1 Auschwitz concentration camp Auschwitz German Nazi concentration and extermination camp (1940–1945) The main entrance to Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp Location of Auschwitz in contemporary Poland Coordinates [1] [1] 50°02′09″N 19°10′42″E Coordinates: 50°02′09″N 19°10′42″E Other names Birkenau Location Auschwitz, Nazi Germany Operated by the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS), the Soviet NKVD (after World War II) Original use Army barracks Operational May 1940 – January 1945 Inmates mainly Jews, Poles, Roma, Soviet soldiers Killed 1.1 million (estimated) Liberated by Soviet Union, January 27, 1945 Notable inmates Viktor Frankl, Maximilian Kolbe, Primo Levi, Witold Pilecki, Edith Stein, Simone Veil, Rudolf Vrba, Elie Wiesel Notable books If This Is a Man, Night, Man's Search for Meaning [2] Website Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum Auschwitz concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager Auschwitz [ˈaʊʃvɪts] ( listen)) was a network of concentration and extermination camps built and operated by the Third Reich in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany during World War II. It consisted of Auschwitz I (the base camp); Auschwitz II–Birkenau (the extermination camp); Auschwitz III–Monowitz (a labor camp to staff an IG Farben factory), and 45 satellite camps. Auschwitz I was first constructed to hold Polish political prisoners, who began to arrive in May 1940. The first extermination of prisoners took place in September 1941, and Auschwitz II–Birkenau went on to become a major site of the Nazi "Final Solution to the Jewish question". From early 1942 until late 1944, transport trains delivered Jews to the camp's gas chambers from all over German-occupied Europe, where they were killed with the pesticide Auschwitz concentration camp 2 Zyklon B. -

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters Ingrid Lewis B.A.(Hons), M.A.(Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of PhD June 2015 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Debbie Ging I hereby declare that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copywright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No: 12210142 Date: ii Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my most beloved parents, Iosefina and Dumitru, and to my sister Cristina I am extremely indebted to my supervisor, Dr. Debbie Ging, for her insightful suggestions and exemplary guidance. Her positive attitude and continuous encouragement throughout this thesis were invaluable. She’s definitely the best supervisor one could ever ask for. I would like to thank the staff from the School of Communications, Dublin City University and especially to the Head of Department, Dr. Pat Brereton. Also special thanks to Dr. Roddy Flynn who was very generous with his time and help in some of the key moments of my PhD. I would like to acknowledge the financial support granted by Laois County Council that made the completion of this PhD possible. -

Las Representaciones Cinematográficas De Los Campos De Concentración Nazi Décadas De 1940 a 1950

VII Jornadas de Sociología de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata “Argentina en el escenario latinoamericano actual: debates desde las ciencias sociales” Las representaciones cinematográficas de los campos de concentración nazi Décadas de 1940 a 1950 Carlos Luciano Dawidiuk UNLu [email protected] El genocidio nazi no siempre ha sido pensado y recordado como se lo hace en nuestros días. Claramente existe en el imaginario colectivo una memoria del Holocausto tejida, no sólo por los testimonios de los supervivientes, sino también por las imágenes creadas por los medios de comunicación y el arte de las últimas décadas. Pero no fue sino hasta el espectacular juicio a Adolf Eichmann en el año 1961 que comenzaría a cobrar fuerza lo que tanto Baer como Huyssen identifican como un proceso de universalización y reconocimiento específico del Holocausto/Shoah como fenómeno único en la historia de la humanidad. Al mismo tiempo, las representaciones cinematográficas del genocidio nazi han crecido tan abrumadoramente en número, que hoy constituyen para muchos prácticamente un género particular. Durante las primeras dos décadas de la posguerra, sin embargo, la situación era totalmente opuesta, pues este fenómeno traumático no había suscitado un gran interés, sufriendo una cierta “invisibilización” en el cine. Por eso creemos interesante acercarnos a las representaciones cinematográficas de los campos de concentración durante esa época en la cual el genocidio nazi no era considerado (al menos no de manera dominante) como un hecho singular ni se había divulgado masivamente. En dicho contexto, se distinguen tanto las representaciones ficcionales como documentales y las particularidades de las diferentes miradas de los realizadores, es decir, atendiendo a qué se elige representar, cómo se lo hace y desde qué posicionamiento.