The Carolina Shaggers: Dance As Serious Leisure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity Book

Activity Book Dance, Dance Revolution #LoveLivesOn Developed for TAPS Youth Programs use. Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………...………………...………………....………….…….1 Dance Games………..........................................................................................2 Dance Doodle……………….……………...……..…………….……………….……………….3 Love Lives On..……..….....………....……………………….…………………...….........…4 Lyric Art…………...…...….…......………………..……..…...……….……......……….…….5 Traditional Dance …..………………....................................................................6 Laugh Yoga….………………………….…………...…….....………………......……….…….7 iRest……………………....………………………………...……………………………………….8 Dancing through the Decades…..…………………………………………...……………..9 Playlist ……………...……..…………………………..…….…………………………….……..10 Unicorn Dance...………...……………………..……………...………………..…....…...…11 Create your own musical instrument..………...……………………………..………..12 Host your own dance party……..…...…….……………………….….….……..………..13 Music Video.………..……………………..…….……………………….….….……..………..14 Disco Pretzels……….……………………………………………………………………………15 Additional Activities………………………………………………….…………...………….16 1 DANCE GAMES TAPS Activity Book DIRECTIONS: Dancing and playing games is a perfect way to have fun with family and friends! Below are a few fun dance games that you can play and try. 1. Memory Moves To play memory moves, have the kids form a circle around the dance floor. Choose one player to go first. That player will step into the center of the circle and make up a dance move. The next player will step into the center and repeat -

Shag Rag January 2007 Vol

Shag Rag January 2007 Vol. XIIII, No1 Dedicated to the Preservation of the Carolina Shag and Beach Music PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by David Rodgers Happy New Year! I hope this next year will be a safe and healthy one for all of our members and their families. We had a wonderful Holiday Party at the Fort Myer community center on Dec. 16th. Thanks to all who helped plan and organize this party. We had a large turn-out of members and guests who kept the dance floor filled for hours while dancing to the great shagging music played by Eddie O’Reilly. It was nice to see so many new faces and welcome back some members we don’t see very often. Thanks to all the members of the NVSC 2006 Board of Directors. We appreciate all the hard work you did to provide NVSC members with a year filled with fun events and opportunities to dance and socialize with others who love to dance the Carolina Shag as much as we do. Your new Board of Directors for 2007 is looking forward to working with all of the members of NVSC to make 2007 an outstanding year for our Club. We are your representatives elected to lead our social and dance organi- zation. We need your ideas and suggestions throughout the year. Look for us on Wednesday nights at Rene’s. Attend the quarterly general membership meetings. Our monthly NVSC Board meetings will be open to any members who have a subject they want to present to the Board or just want to attend as observers. -

Shag Rag July 2013

Shag Rag July 2013 A Proud Member of: Shag Rag July 2013 Vol. XIX, No. 7 Dedicated to the Preservation of the Carolina Shag and Beach Music PRESIDENT’S CORNER by Dave Bushey July! It’s here! The biggest Party of the Year! We’re talking about The Capital Classic! It’s an All-Weekend celebration of Beach Music, the Shag AND The Northern Virginia Shag Club. Put July 26-28 on your calendar. Come out and watch the Sam West, the 2013 National Shag Champion, and his wife Lisa demonstrate how we WISH we could dance. And then, watch our special guests, Shag Team Two Juniors, dance! Even Sam and Lisa are amazed at what THEY can do! And that’s not all! There will be Swing stars and Hand Dance stars and Line dance stars … and … and … workshops from all. And Free Pours (drinks) and Silent Auctions and Barrels of Booze, and did I say there were Free Pours?? Too much liquor? Well, stay at the Hilton Garden Inn. Classic Coordinator Angie Bushey has arranged for some 1990’s-style room rates. How about $69 per night!! With rates like that, why drive home?? And it’s a Reunion, too. This is our 20th year, so we’re celebrating. There will be hundreds of pictures – evidence of the shenanigans of Days Gone By. Come visit with the Founders of our Club! And even the DJ’s are reuniting! Jim Rose and Jerry Scott are returning to their favorite club and Dennis Gehley and Craig Jennings are joining them to take us down Memory Lane with all of our favorite Beach Music. -

Bb&T Blue Skies and Golden Sands Tour

BB&T BLUE SKIES AND GOLDEN SANDS TOUR - PROGRAM NOTES Blue Skies and Golden Sands continues a musical journey that embarked at the start of the North Carolina Symphony’s 75th anniversary season in September 2006. A special pops concert called Blue Skies and Red Earth brought the orchestra together with some of North Carolina’s finest folk musicians for a grand celebration of our state’s musical heritage. Blue Skies and Red Earth thrilled audiences with the sheer depth and breadth of homegrown musical traditions that have evolved over centuries. From haunting Cherokee flute music to the propulsive sounds of the fiddle and banjo, from stately spirituals to ecstatic gospel, from earthy blues to sophisticated jazz, the anniversary program showed the Tar Heel state to be a wellspring of musical treasures. Despite having enlisted dozens of guest artists who performed ten or more styles of music, Blue Skies and Red Earth by no means exhausted North Carolina’s musical resources. A few months after the final performance, planning commenced on a follow-up concert to highlight music oriented more to the state’s eastern shores than the rolling hills and mountains to the west. It began with what seemed like a casual question: “What about beach music?" As most Carolinians know, beach music refers to a body of popular songs that provides just the right mood and rhythms for a popular style of swing dancing called the Carolina Shag. Once heavily associated with beach clubs and dance pavilions from Wilmington, North Carolina to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, shag dancing is performed all over the Southeast nowadays, and many commercial radio stations present the classic beach playlist over the air waves. -

October Birthdays 7 the Chance to Get Know Other Club Members

The Official Newsletter of the Society of Brunswick Shaggers PO BOX 274, Oak Island, NC 28465 Visit our website at: http://www.societyofbrunswickshaggers.com “LIKE” us on FACEBOOK at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/115766191843385/ 2017 The Beach Beat! Message from our President… Board Meeting Minutes 2 September was a great month for the club. We had wonderful turnouts at each dance. Our Operation Uplink Planning 3 Hot Dog and Hamburger cookout night was enjoyed by all. DJs Eddie Baker and Jim Bruno both kept the dance floor full. The Junior Shaggers dance demonstration was a sight to see. Operation Uplink Letter 4 Youth. WOW!!!! I can’t believe that Fall is here already. I am right at 92+ miles in my daily Operation Uplink Flyer 5 ocean swimming trying to have 100 miles at a mile a day for this swim season. Katy and I are enjoying our time dancing. ACSC Workshop Report 6 We continue to need volunteers to sign up to be Door Greeters, to do the 50/50,and to help Hurricane Harvey - FEMA 6 with other duties at upcoming dances. Our Uplink event is the next dance and to make it a Welcome new SOBS & Guests 7 success we need your help. Please contact me if you are willing to lend a hand. Thanks to all who have served the club so far this year. An advantage of assisting the club with events is October Birthdays 7 the chance to get know other club members. It is good to see so many of our members step October DJ Bios 8 up to help with the decorations and cleanup. -

Interactive Animation Dance Game

Interactive Dance Game Name:_______________ Interactive: interacting with a human user, often in a conversational way, to obtain data or commands and to give immediate results or updated information. Dance: to move one's feet or body, or both, rhythmically in a pattern of steps, especially to the accompaniment of music. STEP ONE: RESEARCH at least 3 Dance Styles/Moves by looking at the attached “Dance Styles Categories” sheet and then ANSWER the attached sheet “ Researching Dance Styles & Moves.” STEP TWO: DRAW 3 conceptual designs of possible character designs for your one dance figure. STEP THREE: SCAN your character design into the computer and/or create digitally in Adobe Photoshop or directly in Macromedia Flash. Character Design Graphic Names STEP FOUR: BREAK UP the pieces of your digital character design like the above Character Design Graphic Names . If creating in Adobe Photoshop ensure you save each piece of your digital character with a TRANSPARENT BACKGROUND and save each separately as PSD files . STEP FIVE: IMPORT your character design (approved by teacher) into the program Macromedia Flash – piece by piece by OPENING Macromedia Flash then SELECT from the top of menu -> WINDOW -> SHOW LIBRARY -> STEP SIX: DOUBLE CLICK on the specific Character Design Graphic piece you want to IMPORT (SEE the above photo for specific names of body parts i.e. right arm upper graphic) STEP SEVEN: DELETE the template graphic part and PASTE or choose FILE IMPORT in the one you designed on paper or Adobe Photoshop . (head etc..) STEP EIGHT: RESIZE specific Character Design graphic pieces by RIGHT MOUSE CLICKing on the graphic and choose FREE TRANFORM to scale up or down. -

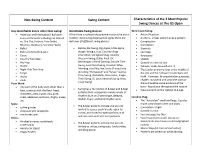

Non-Swing Content Swing Content Characteristics of the 3 Most Popular Swing Dances at the US Open

Non-Swing Content Swing Content Characteristics of the 3 Most Popular Swing Dances at The US Open Any identifiable dance other than swing: Identifiable Swing Dances: West Coast Swing: • American and International Ballroom While there is collegial disagreement about the exact • Action/Reaction Latin and Smooth including not limited number, most swing professionals agree there are • Anchors-- 2 beat pattern ends a pattern to: Cha Cha, Foxtrot, Paso Doble, well over 20 different swing dances: • Compression Rhumba, Quickstep, Viennese Waltz • Connection • Ballet • Balboa, Bal Swing, Big Apple, Little Apple, • Elasticity • Ballroom Smooth & Latin Boogie Woogie, Bop, Carolina Shag, • Leverage • Ceroc Charleston, Collegiate Shag, Country • Resistance • Country Two-Step Western Swing, Dallas Push, DC • Stretch • Hip Hop (Washington) Hand Dancing, Double Time • Danced in a shared slot • Hustle Swing, East Coast Swing, Houston Whip, • Follower walks forward on 1-2 • Night Club Two-Step Jitterbug, Jive/Skip Jive, Lindy (Flying Lindy • The Leader primarily stays in the middle of • Tango including “Hollywood” and “Savoy” styles), the slot and the Follower travels back and • Waltz Pony Swing, Rockabilly, Shim Sham, Single forth. However, for presentation purposes, Time Swing, St. Louis Imperial Swing, West • Zouk Leaders may bend and scroll the slot but Coast Swing Floor Work: there should be some evidence of the • Any part of the body part, other than a basic- foundation throughout the routine • Swing has a foundation of 6-beat and 8-beat foot, contacts with the floor: head, • Pulse (accent) on the Upbeat (2,4,6,8). patterns that incorporate a wide variety of shoulders, arms, hands, ribs, back, rhythms built on 2-beat single, delayed, chest, abdomen, buttocks, thighs, knees, Carolina Shag: double, triple, and blank rhythm units. -

July/August 2012 President’S Letter … by Wes Kirchner the Next Few Months Have a Lot in the Capitol Classic, the Northern This Year

The Bugle Battlefield Boogie Club CREATE DANCE HISTORY CREATE A MEMORY Fredericksburg, Virginia Vol. 7 No. 4 July/August 2012 President’s Letter … by Wes Kirchner The next few months have a lot in The Capitol Classic, the Northern this year. store for us all. Many parties and Virginia Shag Club annual party Of course it events are planned and will give us on July 21st, is one that is a must will be at lots of opportunities to dance and when it comes to parties. This was the Freder- socialize. Cool evenings and hot the first party that Shirley and I icksburg days are the perfect recipe for fun. attended when we were beginner Country Many of us will be doing some kind dancers. Although new to shag- Club (think of travelWing to and from parties, ging, we felt welcomed by every- delicious some as far away as Florida at the one, and that same feeling is evi- mashed pota- ACSC Summer Workshop. Luckily, dent starting at the registration toes) which has hosted our club for we have some really nice parties here desk. Plan on attending this one if several years now. We are very for- in our own backyard. at all possible. You will be glad you tunate to have Hall of Fame DJ did. This year’s classic has a Ha- Butch Metcalf providing the eve- waiian theme. ning’s tunes. Butch is one of the JULY/AUGUST most well-known and requested At the Classic, the DJ is the fabu- beach music DJ’s. Be sure to get lous Mike Harding, who you will Page 1 President’sLetter your tickets soon! most likely remember from play- Page 2 BBC Sock Hop ing at SOS. -

The Carolina Shag

The Carolina Shag Reference notes from your “Basic” shag lesson History The dance originated sometime in the 1930’s but really took root in the 40’s as the war was closing down. People had time to go the beach and relax, and of course dance. Music of those times was being played more and more on the radio. The Lindy Hop, The Big Apple and Jitterbug were popular dances. Most say the Shag was derived from those earlier dances, but with a “Southern style”. It was called “Shagging” because in the earlier days you danced on the beach and had to shift – shag thru the sand. The “Shag” is intensely SOUTHERN, and the capital or mecca eventually became North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. What you are learning today is the Carolina Shag and the music we dance to has been coined “Beach Music” rooted from R&B music that has a gusty backbeat. The Shag used to be a “Peacock” dance where the men did most of the steps or patterns showing off and women held the basic and made the men look good. Over the years it has become more balanced where the emphasis is on “together” steps or “mirror” steps. General Rules The Shag is not a bouncy dance. There is very little to no upper body movement. Dedicate the energy and focus to the legs. Hold your upper body straight without bending at the waist. Keep your knees slightly bent while taking small controlled steps. Dance on the balls of your feet, not your toes. Keep hands still as though they were on a post and on the basic, keep your elbows pointed down. -

The Shaggin' Shews

Lake Norman Shag Club Volume 5 Issue 4 April 2016 THE SHAGGIN’ SHEWS Message from Your President INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Happy Spring LNSC! Yep, spring is here and here to stay. Warmer President’s Message Page 1 weather, flowers, POLLEN and Spring SOS. Yeah! Marianna Hass Page 2 SOS starts April 15. 10 days of dancing, fun, socializing and wonder- ful music. Spring break for us Shaggers. Saturday, April 23 is the Birthdays Page 3 Parade. Pats Cohee and Kathy Sapp have planned a great entry for Recipes Page 4 us. We need all members to participate. You will not have to work. Just arrive and enjoy! LNSC Info Page 5 Speaking of SOS, if you are going and do not have your SOS card, “The Shag” Page 6 please contact Wanda Cavin. She will be happy to get a card to you. Joys & Concerns Page 7 I also want to take this time to remind you again that our May meeting will be held on Friday, May 6, instead of Saturday, so mark Note from your editor Page 8 your calendars now! Club Information Page 9 I want to issue a challenge to all our members. Patsy Fuller works Pictures Page10-14 very hard to create an informative and entertaining newsletter. Be- ing a past editor of the newsletter, I can tell you how very hard this Flyer Page 15 job is, without the contributions of the members. I am asking that all of you consider sending an article, pictures or recipes to Patsy. Lots of you travel to other shag club parties and events. -

Florence Shag Club March 2019 Newsletter

Florence Shag Club March 2019 Newsletter Hello FSC Members, It was a lovely Valentines Party. I extend a huge thank you to our members for the wonderful food and party preparation and especially for the outstanding attendance. Our next party will be the St. Paddy’s Party scheduled March 15th. We are selling tickets for a chance to win a Leprechaun’s Basket Full of Surprises to be given away at the party. Tickets are $5.00 each and are on sale Friday nights at the Circle Fountain. You do not have to be present to win. We will call you should your name be selected. Details of the FSC Golf Tournament have come together. It’s scheduled on May 23rd at the Florence Country Club. The flyer and registration form are posted on the Flyers Page on our website, www.florenceshagclub.com. We are looking for businesses or groups that will sponsor a hole at $100 a hole. The sponsor’s name will be displayed at each hole as well as listed on our website and in our newsletter. We will be glad to post their business cards on our website for the rest of the year as an advertising incentive for them. Help us spread the word. The Circle Fountain owners have asked that we not have a DJ scheduled the following Fridays this year; March 1st, April 26, May 3, September 13 and 20th due to shag events at the beach. Please respect their decisions and remember to thank them for allowing the FSC to dance on Friday nights. -

Resident Lifestyles Clubs and Contacts 8/27/2021

1 of 188 Resident Lifestyles Clubs and Contacts 8/27/2021 To Search: Ctrl + F Search box will appear. Type in a keyword, then hit Enter. Apple Computers to Search: Command F Club / Activity Name Location Leader Group Website Email Address Phone Number CSS La .45 Sidekicks - Call for Info Hacienda Kevin Yeo 1013 Amarillo Pl [email protected] (605) 999-7687 129 Amigos qF@6PM Coconut Cove Linda Maloney NA [email protected] (352) 561-4808 CSS 152 & Friends - Call for Info SeaBreeze Barbara McGrath 1846 Barksdale Drive [email protected] (440) 821-5290 200 Ladies' Club 2,4W@9AM Burnsed Gail Hole 1011 Pickering Path [email protected] (970) 227-0003 2012 Discussion Group 2,4W@3PM Bridgeport Richard Matwyshen NA [email protected] (352) 751-0365 26er's Club 2Meven@6PM La Hacienda Barbara LoPiccolo 1320 Augustine Drive [email protected] (732) 618-7658 26er's West Ladies' Lunch 2TH@11:30AM El Santiago Marilynn Miller 501 Chamber Street [email protected] (262) 442-9805 2nd Honeymoon Club 1M@6:30PM Savannah Mitchell Sheinbaum www.2ndhoneymoonclub.com [email protected] (352) 751-4138 4 O'Clock Club 1Wx7,8@4PM Chula Vista Richard Petulla 518 Chula Vista [email protected] (352) 750-5641 4 Season Singles 2SA@5:30PM SeaBreeze Holly Weller NA [email protected] (352) 430-6007 5 Streets East 1SA2,5,10,12@6PM Burnsed Kathy Dawson 3518 Countryside Path [email protected] (352) 391-6446 A New Vibrant You 2W@6:30PM Laurel Manor Richard Matwyshen NA [email protected] (352) 751-0365 AARP DSP Colony Cottage Colony Cottage Chester Kowalski 2760 Midland Terrace [email protected] (352) 430-1833 AARP DSP Laurel Manor Laurel Manor Chester Kowalski 2760 Midland Terrace [email protected] (352) 430-1833 2 of 188 Resident Lifestyles Clubs and Contacts 8/27/2021 To Search: Ctrl + F Search box will appear.