Bb&T Blue Skies and Golden Sands Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twist”—Chubby Checker (1960) Added to the National Registry: 2012 Essay by Jim Dawson (Guest Post)*

“The Twist”—Chubby Checker (1960) Added to the National Registry: 2012 Essay by Jim Dawson (guest post)* Chubby Checker Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” has the distinction of being the only non-seasonal American recording that reached the top of “Billboard’s” pop charts twice, separately. (Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” topped the holiday tree in 1942, 1945, and 1947). “The Twist” shot to No. 1 in 1960, fell completely off the charts, then returned over a year later like a brand new single and did it all over again. Even more remarkable was that Checker’s version was a nearly note-for- note, commissioned mimicry of the original “The Twist,” written and recorded in 1958 by R&B artist Hank Ballard and released as the B-side of a love ballad. Most remarkable of all, however, is that Chubby Checker set the whole world Twisting, from Harlem clubs to the White House to Buckingham Palace, and beyond. The Twist’s movements were so rudimentary that almost everyone, regardless of their level of coordination, could maneuver through it, usually without injuring or embarrassing themselves. Like so many rhythm and blues songs, “The Twist” had a busy pedigree going back decades. In 1912, black songwriter Perry Bradford wrote “Messin’ Around,” in which he gave instructions to a new dance called the Mess Around: “Put your hands on your hips and bend your back; stand in one spot nice and tight; and twist around with all your might.” The following year, black tunesmiths Chris Smith and Jim Burris wrote “Ballin’ the Jack” for “The Darktown Follies of 1913” at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre, in which they elaborated on the Mess Around by telling dancers, “Twist around and twist around with all your might.” The song started a Ballin’ the Jack craze that, like nearly every new Harlem dance, moved downtown to the white ballrooms and then shimmied and shook across the country. -

The Timelessness of the King's Busketeers: a Splash Into Sea

The Timelessness of The King’s Busketeers: A splash into sea shanties Sea Shanties are typically not my preferred listening, but my recent research into the genre as a whole has yielded some fascinating results. Long before TikTok made it trending, The King’s Busketeers – Joshua Gannon-Salomon, Andrew Prete, and Sam Atwood – were continuing the traditions of many sailors before them hundreds of years in the making. The King’s Busketeers are carrying these traditions forward with their traditional, yet updated sound. Joshua provided a bit of additional context for their work: “One thing the sea shanty trend has demonstrated clearly, is that folk music is not a genre but a process. Shantymen in the days of sail were constantly rehashing old songs into new, taking inspiration anywhere a good rhythm for hauling or working the capstan could be found.” Joshua spoke of the interesting time of history we’re in that mirrors the old world into which the shanty genre was born: “Many articles have pointed out interesting parallels between modern shanty fans under pandemic conditions and the confined, monotonous, overworked and precarious lives of the sailors who sang them. We have comforts they never dreamed of, and their work was intensely social rather than isolated, but suddenly many more people feel solidarity with the sailors of old, their exploitation at the hands of captains and empires, and their lust for life in spite of it. If COVID-19 is today’s stormy voyage, then our visions of post-pandemic celebration parallel the sailors’ dreams of the bars and bawdy houses in the next port.” That might be why shanties are having the cultural moment that they are. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

Unit Will Provide a Way to Connect Science Through Aquatic Organisms and Human Endeavors, Historically and Musically

Songs of the Sea, Above and Below Laurie Bailey Introduction Sea shanties are a part of our musical and nautical history. Shanties provided a strong beat for sailors to work in unison. They described the adventures and trials of sailors and entertained sailors who sailed the seas for up to four years at a time. Shanties tend to be “catchy” and therefore easily learned. In addition, they were written in prose easily understood by those with little education1. To our benefit, shanties provide a type of historical record of sea life in the 18th and 19th centuries. Shanties usually have many verses but almost always include a chorus when all the sailors can sing together. I think this will be a useful tool to help my students participate in singing the shanties. Discussing whales and their communication skills will be a great way to talk to my students about how singing is a way of communication for them and for humans. This unit will provide a way to connect science through aquatic organisms and human endeavors, historically and musically. Rationale Castle Hills Elementary School, located on Moores Lane in New Castle, Delaware, is a school for students in Kindergarten through fifth grade. Enrollment during the school year 2014-2015 was 658. Slightly over one third of the population is African American. Slightly under one third is white and 26% of the students are Hispanic. Just over half of the student population is considered to be Low Income with about 17% who speak another language at home. Fewer than 10% of the students have special needs.2 As I write this paper, this is to be my fourth week at the school, having been reassigned from a school with a population of students with severe physical and cognitive disabilities. -

INTRODUCTION the Arrangements

5 INTRODUCTION Welcome to The Language of Folk 1. This book is meant as an introduction to the world of folk song and is no more than a drop in the ocean in terms of the range of song types, subject matter, melodies and vocal styles found in folk music. The majority of the songs in this collection have their origins in the British Isles, though one or two come from America or further afield. This book brings together songs from different ages. Many are very old, although in some cases they cannot easily be traced further back than the the folk music revivals of the 1920s or 1950s–60s. Folk song, however, is a living tradition, so this book also includes modern songs that have been assimilated into the folk music tradition in recent years; although not ‘traditional’ in the usual sense, they have been included here because they are fantastic to sing and would happily sit in any folk singer’s repertoire. Musicians and audiences often refer to ‘the folk music community’ when talking about the music in its modern setting. There are thousands of people singing, playing, dancing to and listening to this music, and these people form an active community with shared interests. The music is inclusive, so those new to the folk tradition are encouraged and welcomed. ‘Sing-a-rounds’ and ‘sessions’ are commonplace within the UK and Ireland; these are situations (often in a pub or in someone’s home) where anyone is welcomed to sing and play music together. The intention is to share, not to perform, and they are a fantastic setting in which to try out new songs. -

Activity Book

Activity Book Dance, Dance Revolution #LoveLivesOn Developed for TAPS Youth Programs use. Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………...………………...………………....………….…….1 Dance Games………..........................................................................................2 Dance Doodle……………….……………...……..…………….……………….……………….3 Love Lives On..……..….....………....……………………….…………………...….........…4 Lyric Art…………...…...….…......………………..……..…...……….……......……….…….5 Traditional Dance …..………………....................................................................6 Laugh Yoga….………………………….…………...…….....………………......……….…….7 iRest……………………....………………………………...……………………………………….8 Dancing through the Decades…..…………………………………………...……………..9 Playlist ……………...……..…………………………..…….…………………………….……..10 Unicorn Dance...………...……………………..……………...………………..…....…...…11 Create your own musical instrument..………...……………………………..………..12 Host your own dance party……..…...…….……………………….….….……..………..13 Music Video.………..……………………..…….……………………….….….……..………..14 Disco Pretzels……….……………………………………………………………………………15 Additional Activities………………………………………………….…………...………….16 1 DANCE GAMES TAPS Activity Book DIRECTIONS: Dancing and playing games is a perfect way to have fun with family and friends! Below are a few fun dance games that you can play and try. 1. Memory Moves To play memory moves, have the kids form a circle around the dance floor. Choose one player to go first. That player will step into the center of the circle and make up a dance move. The next player will step into the center and repeat -

Steve Waksman [email protected]

Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2010)v1i1.9en Live Recollections: Uses of the Past in U.S. Concert Life Steve Waksman [email protected] Smith College Abstract As an institution, the concert has long been one of the central mechanisms through which a sense of musical history is constructed and conveyed to a contemporary listening audience. Examining concert programs and critical reviews, this paper will briefly survey U.S. concert life at three distinct moments: in the 1840s, when a conflict arose between virtuoso performance and an emerging classical canon; in the 1910s through 1930s, when early jazz concerts referenced the past to highlight the music’s progress over time; and in the late twentieth century, when rock festivals sought to reclaim a sense of liveness in an increasingly mediatized cultural landscape. keywords: concerts, canons, jazz, rock, virtuosity, history. 1 During the nineteenth century, a conflict arose regarding whether concert repertories should dwell more on the presentation of works from the past, or should concentrate on works of a more contemporary character. The notion that works of the past rather than the present should be the focus of concert life gained hold only gradually over the course of the nineteenth century; as it did, concerts in Europe and the U.S. assumed a more curatorial function, acting almost as a living museum of musical artifacts. While this emphasis on the musical past took hold most sharply in the sphere of “high” or classical music, it has become increasingly common in the popular sphere as well, although whether it fulfills the same function in each realm of musical life remains an open question. -

Constructing Robert Johnson Sean Lorre

Constructing Robert Johnson Sean Lorre I don’t think I’d even heard of Robert Johnson when I first found [King of the Delta Blues Singers (1961)]; it was probably fresh out. I was around fifteen or sixteen, and it came as something of a shock to me that there could be anything that powerful... It was almost as if he felt things so acutely that he found it almost unbearable…. At first it was almost too painful, but then after about six months I started listening, and then I didn't listen to anything else. Up until the time I was 25, if you didn't know who Robert Johnson was I wouldn't talk to you. -Eric Clapton1 I was thirteen years old when Woodstock-era nostalgia swept through my small suburban world in the early 1990s. By that time, I had amassed a large collection of classic rock LPs including my personal favorites, Cream’s Greatest Hits and Led Zeppelin IV. In the year or so following, on the recommendations of my local record store clerks and friends in the know, I picked up a copy of the brand new Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings (1990). These most trusted of advisors let it be known that if I liked Eric Clapton, then I would love Johnson, because he was “the real deal,” “where rock n’ roll came from.” When I brought the boxed set home – cassettes, mind you, not CDs – I poured over the liner notes before popping in the tapes. Following an 8,000-word essay about the greatness of Robert Johnson divided into sections entitled “The Man” and “The Music,” came the testimonial of my idol, Clapton himself, who 1 The Complete Recordings 1990, 22 128 Musicological Explorations professed his love for Johnson in no uncertain terms, stating “I have never found anything more deeply soulful than Robert Johnson. -

Paper for B(&N

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 9 • No. 9 • September 2019 doi:10.30845/ijhss.v9n9p4 Biographies of Two African American Women in Religious Music: Clara Ward and Rosetta Tharpe Nana A. Amoah-Ramey Ph.D. Indiana University Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies College of Arts and Sciences Ballantine Hall 678 Bloomington IN, 47405, USA Abstract This paper‟s focus is to compare the lives, times and musical professions of two prominent African American women— Clara Ward and Rosetta Thorpe — in religious music. The study addresses the musical careers of both women and shows challenges that they worked hard to overcome, and how their relationship with other musicians and the public helped to steer their careers by making them important figures in African American gospel and religious music. In pursuing this objective, I relied on manuscripts, narratives, newspaper clippings, and published source materials. Results of the study points to commonalities or similarities between them. In particular, their lives go a long way to confirm the important contributions they made to religious music of their day and even today. Keywords: African American Gospel and Religious Music, Women, Gender, Liberation, Empowerment Overview This paper is structured as follows: It begins with a brief discussion of the historical background of gospel and sacred music. This is followed by an examination of the musical careers of Clara Ward and Rosetta Thorpe with particular attention to the challenges they faced and the strategies they employed to overcome such challenges; and by so doing becoming major figures performing this genre (gospel and sacred music) of music. -

Clyde Mcphatter 1987.Pdf

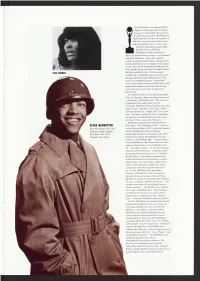

Clyde McPhatter was among thefirst | singers to rhapsodize about romance in gospel’s emotionally charged style. It wasn’t an easy stepfor McP hatter to make; after all, he was only eighteen, a 2m inister’s son born in North Carolina and raised in New Jersey, when vocal arranger and talent manager Billy | Ward decided in 1950 that I McPhatter would be the perfect choice to front his latest concept, a vocal quartet called the Dominoes. At the time, quartets (which, despite the name, often contained more than four members) were popular on the gospel circuit. They also dominated the R&B field, the most popular being decorous ensembles like the Ink Spots and the Orioles. Ward wanted to combine the vocal flamboyance of gospel with the pop orientation o f the R&B quartets. The result was rhythm and gospel, a sound that never really made it across the R &B chart to the mainstream audience o f the time but reached everybody’s ears years later in the form of Sixties soul. As Charlie Gillett wrote in The Sound of the City, the Dominoes began working instinctively - and timidly. McPhatter said, ' ‘We were very frightened in the studio when we were recording. Billy Ward was teaching us the song, and he’d say, ‘Sing it up,’ and I said, 'Well, I don’t feel it that way, ’ and he said, ‘Try it your way. ’ I felt more relaxed if I wasn’t confined to the melody. I would take liberties with it and he’d say, ‘That’s great. -

Theatricals Music Features S> F

Theatricals Music Features S> f anco company with headquarters the first ™E here, generously put up MILLS BROTHERS PAY FT trophy, which will be awarded the Now! The True Inside Stories GOSSIP0F Incidentally the award winners.* successes Insurance of America's most famous colored was not named after the ALLEY CAL' V INFORMAL ur- Walter White, but after the nickname Behind big names like Marian Anderson, MOVIE LOTS company, George W. Carver, Joe Louts, and scores of others, there arc of California, “The Golden State.” stories never yet tola that are full of thrills and inspiration* HARRY LEVETTE Read TOPS for the astounding inside truth about the rise of By and As soon as !l" th*3 votes al'° ’n< a these great Americans. TOPS takes you into their private public lives and tells the things you want to know about will be held and of its kind to public reception them. TOPS is the first and only publication the and achievements of outstanding Gol- the winner pei*sonally presented bring you personalities Hollywood—(ANP)—The colored people. Get a copy at yom newsstand today. award is the newest with the beautiful tro- A A A A A. A. ▲ A A A A. A A A. den State Art expensive ▼ ▼ /VVVVWVvWVV V V v v v v v v ^ x in all-colored cast mo- departure phy’. OF: V this READ TOPS FOR THE .SENSATIONAL SOCCESS STORIES tion picture circles and although The judges asked to serve > MARIAN ANDERSON WALTER WHITE V has made it debut it were Messr. Robert E Ab- > the it modestly year She bad I chance in 360, jel made good, Tbt article by the Secretary of / \ It alone It De- h one the world‘ t grealeit N.A.A.C.P. -

8/1/15 Slagg Brothers Rhythm & Blues, Soul & Grooves Show

8/1/15 Slagg Brothers Rhythm & Blues, Soul & Grooves Show Dance to the Music [Single 1968, influential in the formation and popularization of the musical subgenre of 2:59 Sly & the Family Stone Master] psychedelic soul and helped lay the groundwork for the development of funk music. Backslop 2:33 Baby Earl & The Trinidads Born in Memphis in 1928. Best known for his 1952 singles, "Booted", "No More Do The Chicken (Dance With 2:35 Rosco Gordon Doggin'" and "Just a Little Bit". In 1962, he gave up the music industry and moved to You) New York where he became a partner in a laundry business with his wife. 1965, it was the group's fourth single and the first to achieve success. Featured on Let Her Dance 2:33 Bobby Fuller Four the soundtrack of Fantastic Mr. Fox 1964. Carl Wilson's first recognised writing contribution to a Beach Boys single, his Dance, Dance, Dance 2:00 The Beach Boys contribution being the song's primary guitar riff and solo. Features Glen Campbell on acoustic guitar The 'Carolina Shag' is a partner dance done primarily to Beach Music (100-130+ The Shag (is Totally Cool) 2:13 Billy Graves beats per minute). Still is the state dance of Carolina. The Madison Time, Pt 1 3:08 Ray Bryant Combo Released in 1960, featured in the 1988 movie Hairspray. Twistin' The Night Away 2:44 Sam Cooke Written and recorded by Sam Cooke in 1962. Written by Johnny Otis and originally released as a single in 1958. Lyrics are about a Willie & the Hand Jive 2:37 Johnny Otis Show man who became famous for doing a dance with his hands 1983, from Canada.