Part Iv the Phytogeographical Subdivision of Cuba (With the Contribution of O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Native Tree Species by an Hispanic Community in Panama Author(S): Salomón Aguilar and Richard Condit Source: Economic Botany, Vol

Use of Native Tree Species by an Hispanic Community in Panama Author(s): Salomón Aguilar and Richard Condit Source: Economic Botany, Vol. 55, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 2001), pp. 223-235 Published by: Springer on behalf of New York Botanical Garden Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4256423 . Accessed: 29/07/2011 18:56 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=nybg. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. New York Botanical Garden Press and Springer are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic Botany. http://www.jstor.org USE OF NATIVE TREE SPECIES BY AN HISPANIC COMMUNITY IN PANAMA1 SALOMON AGUILAR AND RICHARD CONDIT Aguilar, Salomon and Richard Condit (Centerfor Tropical Forest Science, Smithsonian TropicalResearch Institute,Unit 0948, APO AA 34002-0948 USA;fax 507-212-8148 (Pana- ma); email [email protected]). -

SPC Beche-De-Mer Information Bulletin Has 13 Original S.W

ISSN 1025-4943 Issue 36 – March 2016 BECHE-DE-MER information bulletin Inside this issue Editorial Rotational zoning systems in multi- species sea cucumber fisheries This 36th issue of the SPC Beche-de-mer Information Bulletin has 13 original S.W. Purcell et al. p. 3 articles relating to the biodiversity of sea cucumbers in various areas of Field observations of sea cucumbers the western Indo-Pacific, aspects of their biology, and methods to better in Ari Atoll, and comparison with two nearby atolls in Maldives study and rear them. F. Ducarme p. 9 We open this issue with an article from Steven Purcell and coworkers Distribution of holothurians in the on the opportunity of using rotational zoning systems to manage shallow lagoons of two marine parks of Mauritius multispecies sea cucumber fisheries. These systems are used, with mixed C. Conand et al. p. 15 results, in developed countries for single-species fisheries but have not New addition to the holothurian fauna been tested for small-scale fisheries in the Pacific Island countries and of Pakistan: Holothuria (Lessonothuria) other developing areas. verrucosa (Selenka 1867), Holothuria cinerascens (Brandt, 1835) and The four articles that follow, deal with biodiversity. The first is from Frédéric Ohshimella ehrenbergii (Selenka, 1868) Ducarme, who presents the results of a survey conducted by an International Q. Ahmed et al. p. 20 Union for Conservation of Nature mission on the coral reefs close to Ari A checklist of the holothurians of Atoll in Maldives. This study increases the number of holothurian species the far eastern seas of Russia recorded in Maldives to 28. -

Keel, S. 2005. Caribbean Ecoregional Assessment Cuba Terrestrial

CARIBBEAN ECOREGIONAL ASSESSMENT Cuba Terrestrial Report July 8, 2005 Shirley Keel INTRODUCTION Physical Features Cuba is the largest country in the Caribbean, with a total area of 110,922 km2. The Cuba archipelago consists of the main island (105,007 km2), Isla de Pinos (2,200 km2), and more than one thousand cays (3,715 km2). Cuba’s main island, oriented in a NW-SE direction, has a varied orography. In the NW the major mountain range is the Guaniguanico Massif stretching from west to east with two mountain chains of distinct geological ages and composition—Sierra de los Organos of ancient Jurassic limestone deposited on slaty sandstone, and Sierra del Rosario, younger and highly varied in geological structure. Towards the east lie the low Hills of Habana- Matanzas and the Hills of Bejucal-Madruga-Limonar. In the central part along the east coast are several low hills—from north to south the Mogotes of Caguaguas, Loma Cunagua, the ancient karstic range of Sierra de Cubitas, and the Maniabón Group; while along the west coast rises the Guamuhaya Massif (Sierra de Escambray range) and low lying Sierra de Najasa. In the SE, Sierra Maestra and the Sagua-Baracoa Massif form continuous mountain ranges. The high ranges of Sierra Maestra stretch from west to east with the island’s highest peak, Pico Real (Turquino Group), reaching 1,974 m. The complex mountain system of Sagua-Baracoa consists of several serpentine mountains in the north and plateau-like limestone mountains in the south. Low limestone hills, Sierra de Casas and Sierra de Caballos are situated in the northeastern part of Isla de Pinos (Borhidi, 1991). -

Ornithophily in the Genus Salvia L. (Lamiaceae)

Ornithophily in the genus Salvia L. (Lamiaceae) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades „Doktor der Naturwissenschaften“ am Fachbereich Biologie der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Petra Wester geb. in Linz/Rhein Mainz, 2007 Kapitel 2 dieser Arbeit wurde veröffentlicht beim Springer Verlag unter: Wester, P. & Claßen-Bockhoff, R. (2006): Hummingbird pollination in Salvia haenkei (Lamiaceae) lacking the typical lever mechanism. Plant Systematics and Evolution 257: 133-146. Kapitel 3 dieser Arbeit wurde veröffentlicht bei Elsevier unter: Wester, P. & Claßen- Bockhoff, R. (2006): Bird pollination in South African Salvia species. Flora 201: 396- 406. Kapitel 5 dieser Arbeit ist im Druck bei Oxford University Press (Annals of Botany) unter: Wester, P. & Claßen-Bockhoff, R. (2007): Floral diversity and pollen transfer mechanisms in bird-pollinated Salvia species. Meinen Eltern gewidmet Contents SUMMARY OF THE THESIS............................................................................................................................. 1 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG....................................................................................................................................... 2 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 3 2 HUMMINGBIRD POLLINATION IN SALVIA HAENKEI (LAMIACEAE) LACKING THE TYPICAL LEVER MECHANISM ..................................................................................................................................... -

TELEMARK BOTANISKE FORENING 2 Listéra 2015, Nr

1 - 2015 TELEMARK BOTANISKE FORENING 2 Listéra 2015, nr. 1 LISTÉRA - Tidsskrift for Telemark Botaniske Forening (NBF, Telemarksavdelingen) 30. årgang, 2015, nummer 1 **************************************************************** ADRESSER OG TELEFONER: TELEMARK BOTANISKE FORENING, org.nr. 989 212 621 Postboks 25 Stridsklev, 3904 Porsgrunn. Girokonto: 0530 3890647 Foreningens e-mail-kontakt: [email protected] Foreningens hjemmeside: www.miclis.no/tbf Kasserer: Åse Halvorsen, [email protected] Tlf.: 35500135 / 91595087 Styremedlem: Esther Broch, [email protected] Tlf.: 35530586 / 90015286 Styremedlem: Christian Kortner, [email protected] Tlf.: 91894169 Styremedlem: Bjørn Erik Halvorsen, [email protected] Tlf.: 35289517 / 91310296 Styremedlem: Trond Risdal, [email protected] Tlf.: 47287740 1. Varamedlem: Øivind Kortner, [email protected] Tlf.: 91541184 2. Varamedlem: Anne Vinorum Tlf.: 35514117 **************************************************************** I redaksjonen: Charlotte Bakke ([email protected]), Norman Hagen ([email protected]), Kåre Homble ([email protected]), Kristin Steineger Vigander ([email protected]) For bilder uten oppgitt fotograf er det forfatteren som er fotograf. Forsidebildet: Lodnestorkenebb Geranium molle. Foto: Kristin Vigander ISSN: 0801 - 9460 Listéra 2015, nr. 1 3 BLÅVEIS Hepatica nobilis Til vanleg veks her ikkje blåveis i Tjønnegrend – kanskje fordi våren er sein og snoen ligg so lenge? Men dei få som er planta her trivst veldig godt, dei spreier seg og kjem med nye blomar kvar vår. Kjende førekomstar er observert i 20-30 år. Dei små frøa hev eit lag med angande olje rundt seg som mauren likar svært godt og dreg med seg. Slik blir dei spreidde omkring. I Kviteseid er det store mengder med blåveis. Det kan knapt vera noko i vegen for å spa opp ei liti tuve og ta med – Sigrid Nordskog, Tjønnegrend TJØNNEGRENDSERIEN 4 Listéra 2015, nr. -

Structural Diversity and Contrasted Evolution of Cytoplasmic Genomes in Flowering Plants :A Phylogenomic Approach in Oleaceae Celine Van De Paer

Structural diversity and contrasted evolution of cytoplasmic genomes in flowering plants :a phylogenomic approach in Oleaceae Celine van de Paer To cite this version: Celine van de Paer. Structural diversity and contrasted evolution of cytoplasmic genomes in flowering plants : a phylogenomic approach in Oleaceae. Vegetal Biology. Université Paul Sabatier - Toulouse III, 2017. English. NNT : 2017TOU30228. tel-02325872 HAL Id: tel-02325872 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02325872 Submitted on 22 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REMERCIEMENTS Remerciements Mes premiers remerciements s'adressent à mon directeur de thèse GUILLAUME BESNARD. Tout d'abord, merci Guillaume de m'avoir proposé ce sujet de thèse sur la famille des Oleaceae. Merci pour ton enthousiasme et ta passion pour la recherche qui m'ont véritablement portée pendant ces trois années. C'était un vrai plaisir de travailler à tes côtés. Moi qui étais focalisée sur les systèmes de reproduction chez les plantes, tu m'as ouvert à un nouveau domaine de la recherche tout aussi intéressant qui est l'évolution moléculaire (même si je suis loin de maîtriser tous les concepts...). Tu as toujours été bienveillant et à l'écoute, je t'en remercie. -

Historical Biogeography of Endemic Seed Plant Genera in the Caribbean: Did Gaarlandia Play a Role?

Received: 18 May 2017 | Revised: 11 September 2017 | Accepted: 14 September 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.3521 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Historical Biogeography of endemic seed plant genera in the Caribbean: Did GAARlandia play a role? María Esther Nieto-Blázquez1 | Alexandre Antonelli2,3,4 | Julissa Roncal1 1Department of Biology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada Abstract 2Department of Biological and Environmental The Caribbean archipelago is a region with an extremely complex geological history Sciences, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, and an outstanding plant diversity with high levels of endemism. The aim of this study Sweden was to better understand the historical assembly and evolution of endemic seed plant 3Gothenburg Botanical Garden, Göteborg, Sweden genera in the Caribbean, by first determining divergence times of endemic genera to 4Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, test whether the hypothesized Greater Antilles and Aves Ridge (GAARlandia) land Göteborg, Sweden bridge played a role in the archipelago colonization and second by testing South Correspondence America as the main colonization source as expected by the position of landmasses María Esther Nieto-Blázquez, Biology Department, Memorial University of and recent evidence of an asymmetrical biotic interchange. We reconstructed a dated Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada. molecular phylogenetic tree for 625 seed plants including 32 Caribbean endemic gen- Emails: [email protected]; menietoblazquez@ gmail.com era using Bayesian inference and ten calibrations. To estimate the geographic range of the ancestors of endemic genera, we performed a model selection between a null and Funding information NSERC-Discovery grant, Grant/Award two complex biogeographic models that included timeframes based on geological Number: RGPIN-2014-03976; MUN’s information, dispersal probabilities, and directionality among regions. -

Piperaceae) Revealed by Molecules

Annals of Botany 99: 1231–1238, 2007 doi:10.1093/aob/mcm063, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org From Forgotten Taxon to a Missing Link? The Position of the Genus Verhuellia (Piperaceae) Revealed by Molecules S. WANKE1 , L. VANDERSCHAEVE2 ,G.MATHIEU2 ,C.NEINHUIS1 , P. GOETGHEBEUR2 and M. S. SAMAIN2,* 1Technische Universita¨t Dresden, Institut fu¨r Botanik, D-01062 Dresden, Germany and 2Ghent University, Department of Biology, Research Group Spermatophytes, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/99/6/1231/2769300 by guest on 28 September 2021 Received: 6 December 2006 Returned for revision: 22 January 2007 Accepted: 12 February 2007 † Background and Aims The species-poor and little-studied genus Verhuellia has often been treated as a synonym of the genus Peperomia, downplaying its significance in the relationships and evolutionary aspects in Piperaceae and Piperales. The lack of knowledge concerning Verhuellia is largely due to its restricted distribution, poorly known collection localities, limited availability in herbaria and absence in botanical gardens and lack of material suitable for molecular phylogenetic studies until recently. Because Verhuellia has some of the most reduced flowers in Piperales, the reconstruction of floral evolution which shows strong trends towards reduction in all lineages needs to be revised. † Methods Verhuellia is included in a molecular phylogenetic analysis of Piperales (trnT-trnL-trnF and trnK/matK), based on nearly 6000 aligned characters and more than 1400 potentially parsimony-informative sites which were partly generated for the present study. Character states for stamen and carpel number are mapped on the combined molecular tree to reconstruct the ancestral states. -

Biodiversity Baseline in the Different Stages of the Project for the 10 Most Important Species

Drafted by: November 2018 Baseline report of amphibians, reptiles, and Haptanthus hazlettii Jilamito Hydroelectric Project Baseline study of amphibians, reptiles and the arboreal species Haptanthus hazlettii in the site of the Jilamito Hydroelectric Project FINAL REPORT Research team: Ricardo Matamoros (Main Coordinator) José Mario Solís Ramos (Herpetologist – Field Coordinator) Carlos M. O'Reilly (Botanist) Josué Ramos Galdámez (Herpetologist) Juan José Rodríguez (Field Technician) Dilma Daniela Rivera (Field Technician) Rony E. Valle (Field Technician) Technical support team and local guides: Hegel Velásquez (INGELSA Technician) - Forest Engineer Omar Escalante (INGELSA Environmental Technician) Nelson Serrano (ICF Tela Technician) Mauro Zavala (PROLANSATE Technician) Alberto Ramírez (Field Guide) José Efraín Sorto (Field Guide) Juan Ramírez (Field Guide) Agustín Sorto Natarén (Field Guide) Manuel Sorto Natarén (Field Guide) José Hernán Flores (Field Guide) Photos on the cover: The arboreal species, Haptanthus hazlettii, found in bloom. In the pictures we observe: Plectrohyla chrysopleura (Climbing frog), Atlantihyla spinipollex (Ceiba stream frog), Duellmanohyla salvavida (Honduran brook frog), Pleistioson sumichrastri (blue tail lizard), Bothriechis guifarroi (green Tamagas, palm viper). 2 Baseline report of amphibians, reptiles, and Haptanthus hazlettii Jilamito Hydroelectric Project 1 Content 2. SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 5 3. INTRODUCTION -

Woody Plant Species Used in Urban Forestry in West Africa: Case Study in Lomé, Capital Town of Togo

Journal of Horticulture and Forestry Vol. 3(1) pp. 21-31, January 2011 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/jhf ISSN 2006-9782 ©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Woody plant species used in urban forestry in West Africa: Case study in Lomé, capital town of Togo Radji Raoufou*, Kokou Kouami and Akpagana Koffi Laboratory of Plant Biology and Ecology, BP 1515 Lomé - Togo. Accepted 23 November, 2010 Many studies have been conducted on the flora of Togo. However, none of them is devoted to the ornamental flora horticulture. This survey aims to establish an inventory of the woody plant species in urban forests of Lomé, the capital town of Togo. It covers the trees planted along the avenues, in the gardens, courtyards, shady trees and trees used as fences for houses or trees at the seaside. In total, 297 plant species belong to 141 genera and 48 families were recorded. They are dominated by 79% of dicotyledonous, 13% of monocotyledonous and 8% of gymnosperms. Families that are best represented in terms of species are those of the Euphorbiaceae, Arecaceae and Acanthaceae. Alien species represent 69% and African species represent 31% out of which 6% are from Togo. According to the current threatening of the natural habitat by human activities, African native plant species could be more useful for ornamental purposes than exotic plants. Key words: Ornamental horticulture, plant flora, green areas, valorisation, native flora. INTRODUCTION Urban forestry refers to trees and forests located in cities, landscape covered with trees for the physical and mental including ornamental and grown trees, street and health has been documented (Ulrich, 1984). -

Brya Ebenus (L.) DC

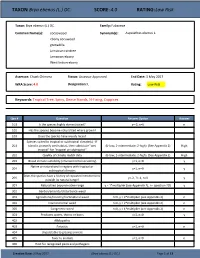

TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Low Risk Taxon: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. Family: Fabaceae Common Name(s): cocoswood Synonym(s): Aspalathus ebenus L. ebony cocuwood grenadilla Jamaican raintree Jamaican-ebony West Indian-ebony Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 3 May 2017 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Spiny, Dense Stands, N-Fixing, Coppices Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens Creation Date: 3 May 2017 (Brya ebenus (L.) DC.) Page 1 of 13 TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. -

Forest Inventory and Analysis National Core Field Guide

National Core Field Guide, Version 5.1 October, 2011 FOREST INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS NATIONAL CORE FIELD GUIDE VOLUME I: FIELD DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES FOR PHASE 2 PLOTS Version 5.1 National Core Field Guide, Version 5.1 October, 2011 Changes from the Phase 2 Field Guide version 5.0 to version 5.1 Changes documented in change proposals are indicated in bold type. The corresponding proposal name can be seen using the comments feature in the electronic file. • Section 8. Phase 2 (P2) Vegetation Profile (Core Optional). Corrected several figure numbers and figure references in the text. • 8.2. General definitions. NRCS PLANTS database. Changed text from: “USDA, NRCS. 2000. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 1 January 2000). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. FIA currently uses a stable codeset downloaded in January of 2000.” To: “USDA, NRCS. 2010. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 1 January 2010). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. FIA currently uses a stable codeset downloaded in January of 2010”. • 8.6.2. SPECIES CODE. Changed the text in the first paragraph from: “Record a code for each sampled vascular plant species found rooted in or overhanging the sampled condition of the subplot at any height. Species codes must be the standardized codes in the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) PLANTS database (currently January 2000 version). Identification to species only is expected. However, if subspecies information is known, enter the appropriate NRCS code. For graminoids, genus and unknown codes are acceptable, but do not lump species of the same genera or unknown code.