THE TROPICAL Garden from the Chief Operating Officer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antibacterial Activity of Leaf Extracts of Spondias Mangifera Wild: a Future Alternative of Antibiotics

Microbiological Communication Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 12(3): 665-668 (2019) Antibacterial activity of leaf extracts of Spondias mangifera Wild: A future alternative of antibiotics Pooja Jaiswal1, Alpana Yadav1, Gopal Nath2 and Nishi Kumari1* 1Department of Botany, MMV, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, Uttar Pradesh, India 2Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, Uttar Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Antibacterial effi cacy of both dry and green leaf extracts of Spondias mangifera was observed by using their methanol, ethanol, and aqueous extracts. Six human pathogenic bacterial strains were selected as test organisms and antibacterial activities were assessed by using disc diffusion method. Maximum inhibition of Enterococcus faecalis was observed by ethanolic dry leaf extract (25.00 ± 0.58). Similarly, methanolic dry leaf extract was very effective against Shigella boydii (25.17±0.44). Higher antibacterial activity was observed by green leaf extracts for other test organisms. Aqueous extract of green leaf showed maximum inhibition (11.50± 0.76) against Staphylococcus aureus. Ethanolic extract of green leaf showed maximum activity (10.17±0.44) against Escherichia coli. Similarly, methanolic extract of green leaf against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus vulgaris showed maximum antibacterial activities, i.e. (15.50±0.29) and (12.50±0.29) respectively. KEY WORDS: ANTIBACTERIAL, BACTERIA, EXTRACT, INHIBITION, SOLVENT INTRODUCTION metabolites such as alkaloids, tannins, fl avonoids, terpe- noids, etc. contribute signifi cant role in developing anti- Since ancient times, we depend on plants or plant microbial properties. After the discovery of antibiotics, products for medicines. Plants serve as source of many our dependence on antibiotics had minimized the use of chemicals and many of them have been identifi ed as such plants. -

Some Interesting Fruits from Tropical Asia

FLORIDA STATE HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 157 SOME INTERESTING FRUITS FROM TROPICAL ASIA WILSON POPENOE United Fruit Company, Guatemala City, Guat. When Dr. Wolfe invited me to present this couragements were so numerous and so defi brief paper before the Krome Memorial In nite that I decided we were too far north; stitute, I grasped the opportunity with par and I moved to Honduras, where, in a lovely ticular pleasure, primarily because it gives little valley three miles from the beach at me a chance to pay tribute to the memory Tela, we started planting mangosteens in of William J. Krome. It was my good for 1925. To give due credit, I should mention tune to see him frequently, back in the early that R. H. Goodell had already planted two days when he was developing an orchard at or three which he had obtained from Dr. Homestead. I felt the impulse of his dynam Fairchild at Washington, and they were pros ic enthusiasm, and I believe I appreciated pering. what he was doing for south Florida and for We obtained seed from Jamaica and from subtropical horticulture. In short, my admi Indo-China, and finally contracted for the ration for him and for his work knew no entire crop produced by an old tree on Lake bounds. Izabal in nearby Guatemala. We had no Yet many results might have been lost had trouble in starting the seedlings, and a year not Mrs. Krome carried on so ably and so or two later we began planting them out in devotedly with the work. -

Interaction of Putative Virulent Isolates Among Commercial Varieties Of

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2020; 9(1): 355-360 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2020; 9(1): 355-360 Interaction of putative virulent isolates among Received: 16-11-2019 Accepted: 18-12-2019 commercial varieties of mango under protected condition Devappa V Department of Plant Pathology, College of Horticulture, UHS Devappa V, Sangeetha CG and Ranjitha N Campus, GKVK Post, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India Abstract Sangeetha CG The present study was undertaken to know the interaction of the putative Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Department of Plant Pathology, isolates from different regions of Karnataka. The cultural characteristics among the 10 isolates studied, College of Horticulture, UHS showed that isolates Cg-1, Cg-2, Cg-4, Cg-5, Cg-6, Cg-7, Cg-8, Cg-10 were circular with smooth margin Campus, GKVK Post, both on 7th and 12th day of inoculation. Excellent sporulation was observed in Cg-8 and Cg-4 isolate, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India good sporulation was observed in Cg-3 and Cg-9 isolates whereas, medium sporulation in Cg-1, Cg-2, Cg-5, Cg-6 and Cg-7 isolates and poor sporulation was observed in Cg-10 isolate. Among the varieties Ranjitha N tested, none of them showed immune and resistant reaction to the disease under shade house condition. Department of Plant Pathology, Dasheri (20%) exhibited moderately resistant reaction, Totapuri (28%) and Himayudhin (29.70%) College of Horticulture, UHS Campus, GKVK Post, exhibited moderately susceptible reaction whereas, Mallika (35%) and Kesar (47.30%) exhibited Bengaluru, Karnataka, India susceptible reaction. Alphanso (62.50%), Neelam (56.20%) and Raspuri (75%) exhibited highly susceptible reaction. -

Road Map for Developing & Strengthening The

KENYA ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR DECEMBER 2014 TRADE IMPACT FOR GOOD The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not formally been edited by the International Trade Centre. ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE KENYAN PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR Prepared for International Trade Centre Geneva, december 2014 ii This value chain roadmap was developed on the basis of technical assistance of the International Trade Centre ( ITC ). Views expressed herein are those of consultants and do not necessarily coincide with those of ITC, UN or WTO. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited my ITC. The International Trade Centre ( ITC ) is the joint agency of the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations. Digital images on cover : © shutterstock Street address : ITC, 54-56, rue de Montbrillant, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Postal address : ITC Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Telephone : + 41- 22 730 0111 Postal address : ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Email : [email protected] Internet : http :// www.intracen.org iii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS Unless otherwise specified, all references to dollars ( $ ) are to United States dollars, and all references to tons are to metric tons. The following abbreviations are used : AIJN European Fruit Juice Association BRC British Retail Consortium CPB Community Business Plan DC Developing countries EFTA European Free Trade Association EPC Export Promotion Council EU European Union FPEAK Fresh Produce Exporters Association of Kenya FT Fairtrade G.A.P. -

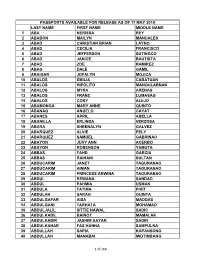

Passports Available for Release As of 17 May 2019

PASSPORTS AVAILABLE FOR RELEASE AS OF 17 MAY 2019 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME 1 ABA NERISSA REY 2 ABABON MAILYN MANUALES 3 ABAD CHRISTIAN BRIAN LAYNO 4 ABAD CECILIA FRANCISCO 5 ABAD JEFFERSON SUTINGCO 6 ABAD JANICE BAUTISTA 7 ABAD ZOE RAMIREZ 8 ABAG DALE GAMIL 9 ABAIGAR JOFALYN MOJICA 10 ABALOS EMILIA CABATUAN 11 ABALOS HIPOLITO MANGULABNAN 12 ABALOS MYRA ARENAS 13 ABALOS FRANZ LUMASAG 14 ABALOS CORY ALEJO 15 ABAMONGA MARY ANNE QUINTO 16 ABANAG ANGELO CAYAT 17 ABANES APRIL ABELLA 18 ABANILLA ERLINDA VERZOSA 19 ABARA SHEENALYN GALVEZ 20 ABARQUEZ ALVIE PELY 21 ABARQUEZ SAMUEL GABRINAO 22 ABAYON JUVY ANN ACERBO 23 ABAYON ROBENSON YAMUTA 24 ABBAS FAHD GARCIA 25 ABBAS RAIHANI SULTAN 26 ABDUCARIM JANET TAGURANAO 27 ABDUCARIM AIMAN TAGURANAO 28 ABDUCARIM PRINCESS ARWINA TAGURANAO 29 ABDUL REWANA SANDAD 30 ABDUL PAHMIA USMAN 31 ABDULA FATIMA PIKIT 32 ABDULAH SARAH GUINTA 33 ABDULGAFAR AISA MADDAS 34 ABDULGANI TARHATA MOHAMAD 35 ABDULJALIL SITTIE NAWAL SADIC 36 ABDULKADIL BAINOT MAMALAK 37 ABDULKADIR JASHIM AAYAN SADIN 38 ABDULKAHAR FAS HANNA SAMPULNA 39 ABDULLAH SAPIA KAPANSONG 40 ABDULLAH MANABAI MIDTIMBANG 1 of 166 PASSPORTS AVAILABLE FOR RELEASE AS OF 17 MAY 2019 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME 41 ABDULLAH NORHATA MANTLI 42 ABDULLAH RUGAYA KAMSA 43 ABDULLAH EDRIS SAMO 44 ABDULLAH MOHD RASUL II WINGO 45 ABDULRAKIM HANIFA BURANTONG 46 ABDURASAD RIRDALIN MAGARIB 47 ABEJERO MARICAR TADIFA 48 ABELARDO DODIE DEL ROSARIO 49 ABELGAS JUMIL TABORADA 50 ABELLA ERIC RITCHIE REX SY 51 ABELLA MARIVIC SILVESTRE 52 ABELLA JERREMY JACOB MONIS 53 ABELLA MARISSA CANILAO 54 ABELLA MELISSA LUCINA 55 ABELLANA RENANTE BUSTAMANTE 56 ABELLANIDA ROSE ANN GAGNO 57 ABELLANO JOHN PAUL ERIA 58 ABELLANOSA JOEL GALINDO 59 ABELLAR MA. -

Tribe Cocoeae)

570.5 ILL 59 " 199 0- A Taxonomic mv of the Palm Subtribe Attaleinae (Tribe Cocoeae) SIDiNLV i\ GLASSMAN UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN BIOLOGY 2891 etc 2 8 Digitized by tine Internet Arcinive in 2011 witii funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/taxonomictreatme59glas A Taxonomic Treatment of the Palm Subtribe Attaleinae (Tribe Cocoeae) SIDNEY F. GLASSMAN ILLINOIS BIOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS 59 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana and Chicago Illinois Biological Monographs Committee David S. Seigler, chair Daniel B. Blake Joseph V. Maddox Lawrence M. Page © 1999 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Manufactured in the United States of America P 5 4 3 2 1 This edition was digitally printed. © This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Classman, Sidney F. A taxonomic treatment of the palm subtribe Attaleinae (tribe Cocoeae) / Sidney F. Classman. p. cm. — (Illinois biological monographs ; 59) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-252-06786-X (pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Palms—Classification. 2. Palm.s—Classification —South America. I. Title. II. Series. QK495.P17G548 1999 584'.5—dc21 98-58105 CIP Abstract Detailed taxonomic treatments of all genera in the subtribe AttaleinaesLve included in the present study. Attalea contains 21 species; 2 interspecific hybrids, A. x piassabossu and A. x voeksii; and 1 intergeneric hybrid, x Attabignya minarum. Orbignya has 1 1 species; 1 interspecific hybrid, O. x teixeirana; 2 intergeneric hybrids, x Attabignya minarum and x Maximbignya dahlgreniana; 1 putative intergeneric hybrid, Ynesa colenda; and 1 unde- scribed putative intergeneric hybrid. -

Partnerships Between Botanic Gardens and Universities in A

SOUTH FLORIDA-CARIBBEAN CONNECTIONS South Florida-Caribbean Connections education for both Caribbean and US students. An official Memorandum of Understanding Partnerships between Botanic between FIU and the University of the West Indies (UWI) facilitates joint supervision of students by Gardens and Universities in a faculty at the two universities. Two students from UWI at Changing Caribbean World Mona (Tracy Commock and Keron by Javier Francisco-Ortega, Brett Jestrow & M. Patrick Griffith Campbell) are currently enrolled in this program, with major advisor Dr. Phil Rose of UWI and the first two authors as co-major advisor and uman activities the subsequent risk of introducing direct resources to them. Additional committee member, respectively. A have had a major non-native invasive species into partners are the USDA Subtropical project led by Commock concerns impact on the flora their environments. Horticulture Research Station of plant genera only found in Jamaica, and fauna of our Miami, led by Dr. Alan Meerow, for while Campbell’s research focuses on planet. Human- Regarding climate change, molecular genetic projects; and the the conservation status of Jamaican driven climate change and the Caribbean countries are facing two International Center for Tropical endemics. The baseline information immediate challenges. The first generated by these two studies will Hcurrent move to a global economy Botany (ICTB), a collaboration is sea-level rise, which is having between FIU, the National Tropical be critical to our understanding of are among the main factors an immediate impact on seashore Botanic Garden (NTBG) and the how climate change can affect the contributing to the current path habitats. -

SPC Beche-De-Mer Information Bulletin Has 13 Original S.W

ISSN 1025-4943 Issue 36 – March 2016 BECHE-DE-MER information bulletin Inside this issue Editorial Rotational zoning systems in multi- species sea cucumber fisheries This 36th issue of the SPC Beche-de-mer Information Bulletin has 13 original S.W. Purcell et al. p. 3 articles relating to the biodiversity of sea cucumbers in various areas of Field observations of sea cucumbers the western Indo-Pacific, aspects of their biology, and methods to better in Ari Atoll, and comparison with two nearby atolls in Maldives study and rear them. F. Ducarme p. 9 We open this issue with an article from Steven Purcell and coworkers Distribution of holothurians in the on the opportunity of using rotational zoning systems to manage shallow lagoons of two marine parks of Mauritius multispecies sea cucumber fisheries. These systems are used, with mixed C. Conand et al. p. 15 results, in developed countries for single-species fisheries but have not New addition to the holothurian fauna been tested for small-scale fisheries in the Pacific Island countries and of Pakistan: Holothuria (Lessonothuria) other developing areas. verrucosa (Selenka 1867), Holothuria cinerascens (Brandt, 1835) and The four articles that follow, deal with biodiversity. The first is from Frédéric Ohshimella ehrenbergii (Selenka, 1868) Ducarme, who presents the results of a survey conducted by an International Q. Ahmed et al. p. 20 Union for Conservation of Nature mission on the coral reefs close to Ari A checklist of the holothurians of Atoll in Maldives. This study increases the number of holothurian species the far eastern seas of Russia recorded in Maldives to 28. -

Review the Conservation Status of West Indian Palms (Arecaceae)

Oryx Vol 41 No 3 July 2007 Review The conservation status of West Indian palms (Arecaceae) Scott Zona, Rau´l Verdecia, Angela Leiva Sa´nchez, Carl E. Lewis and Mike Maunder Abstract The conservation status of 134 species, sub- ex situ and in situ conservation projects in the region’s species and varieties of West Indian palms (Arecaceae) botanical gardens. We recommend that preliminary is assessed and reviewed, based on field studies and conservation assessments be made of the 25 Data current literature. We find that 90% of the palm taxa of Deficient taxa so that conservation measures can be the West Indies are endemic. Using the IUCN Red List implemented for those facing imminent threats. categories one species is categorized as Extinct, 11 taxa as Critically Endangered, 19 as Endangered, and 21 as Keywords Arecaceae, Caribbean, Palmae, palms, Red Vulnerable. Fifty-seven taxa are classified as Least List, West Indies. Concern. Twenty-five taxa are Data Deficient, an indica- tion that additional field studies are urgently needed. The 11 Critically Endangered taxa warrant immediate This paper contains supplementary material that can conservation action; some are currently the subject of only be found online at http://journals.cambridge.org Introduction Recent phylogenetic work has changed the status of one genus formerly regarded as endemic: Gastrococos is now The islands of the West Indies (the Caribbean Islands shown to be part of the widespread genus Acrocomia sensu Smith et al., 2004), comprising the Greater and (Gunn, 2004). Taking these changes into consideration, Lesser Antilles, along with the Bahamas Archipelago, endemism at the generic level is 14%. -

JULY 2016 Our Next Meeting Is Monday, July 18Th at 4701 Golden Gate Parkway Which Is the Golden Gate Community Center

COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER JULY 2016 Our next meeting is Monday, July 18th at 4701 Golden Gate Parkway which is the Golden Gate Community Center. The topic is going to be " Unusual and Rare Fruit Trees that Adapt or May Adapt to Cultivation in Florida". There will not be an August meeting. See you in September Our speaker is Berto Silva, a native Brazilian who specializes in growing rare and unusual fruits. Berto was raised in northeast Brazil where he learned to enjoy several different types of fruits. In the last twenty years, he has experimented growing rare and unusual fruits from all over the world including some varieties native to the Amazon region. He has a spectacular jaboticaba arbor at his home in South Ft. Myers. He is an active member with the Bonita Springs Tropical Fruit Club and with the Caloosa Rare Fruit Exchange. Berto’s collection includes myrciarias, eugenias, pouterias, annonas, mangiferas, and campomanesias. The meeting starts at 7:30 pm at the Community Center, 4701 Golden Gate Parkway in Golden Gate City. The tasting table opens at 7:00 pm. BURDS’ NEST OF INFORMATION THIS and THAT FOR JULY MANGOS MANGOS MANGOS We suggest that you attend: The International Mango Festival is at Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden on July 9 th &10 th from 9am -4pm. Saturday is the better day to go. The University of Florida Collier County Extension on Saturday July 16 th from 9am – 1pm presents “Alternatives to Citrus - Mango and Fruit Trees for you yard” with Steve from Fruit Scapes & the Burds. -

COMPASSION a Festival of Musical Passions JUNE 5–15 GREAT ARCHETYPAL STORIES of SUFFERING, EMPATHY, and HOPE

COMPASSION A FESTIVAL OF MUSICAL PASSIONS JUNE 5–15 GREAT ARCHETYPAL STORIES OF SUFFERING, EMPATHY, AND HOPE CONSPIRARE.ORG 1 COMPASSION Diversify your Assets: FESTIVAL Invest in the Arts. PIETÀ JUNE 5-7, FREDERICKSBURG & AUSTIN CONSIDERING MATTHEW SHEPARD DURUFLÉ – REQUIEM JUNE 8, AUSTIN A GNOSTIC PASSION JUNE 10, AUSTIN J.S. BACH – ST. MATTHEW PASSION JUNE 14-15, AUSTIN We applaud the artists and patrons who invest in our community. CRAIG HELLA JOHNSON Artistic Director & Conductor ROBERT KYR & JOHN MUEHLEISEN Composers & Speakers SEASON SUSTAINING UNDERWRITER tm 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 5-6 PROGRAM: PIETÀ ...............................................................................................7 ARTISTS: PIETÀ ..................................................................................................8 PROGRAM NOTES: PIETÀ ............................................................................ 9-10 PROGRAM: CONSIDERING MATTHEW SHEPARD/REQUIEM .......................... 11 Welcome to the Conspirare comPassion Festival. ARTISTS: CONSIDERING MATTHEW SHEPARD/REQUIEM .............................. 12 Whether you find yourself in the middle of a PROGRAM NOTES: CONSIDERING MATTHEW SHEPARD/REQUIEM .............. 13 performance or at a workshop, I invite you to PROGRAM: A GNOSTIC PASSION.................................................................... 14 take this time to deeply experience -

Retail Dietitian Activation

NATIONAL MANGO BOARD RETAIL DIETITIAN ACTIVATION KIT WHAT’S INSIDE Q1: Health and Wellness Activation Ideas 4 How to Cut a Mango 5 Smoothie Demonstration Guide 6 Blog/Newsletter Inspiration 8 Social Media Posts 9 Mango Rose Tutorial 9 Q2: Plant-based Activation Ideas 10 Mango Varieties 11 How to Choose a Mango 11 Cinco de Mango Segment Execution Guide 12 Social Media Posts 15 Q3: Summer Celebrations and Back to School Activation Ideas 16 Grilled Mango Recipe Demonstration Guide 17 Mango a Day, the Super Fun Way 18 Social Media Posts 19 Q4: Healthy Holidays Activation Ideas 20 Pistachio Crusted Mango Cheese Log Recipe 21 Celebrate Healthy Skin Month with Mangos 22 Social Media Posts 23 GET TO KNOW THE KING OF FRUITS Mangos are the sunniest fruit in the produce aisle and they’re available year round, yet many shoppers only tend to think of mangos in the spring and summer. Sometimes shoppers pass over mangos because they’re unsure about how to choose them, or they don’t know how to cut or prepare mangos. Others can’t find mangos or simply don’t think about them when shopping for produce. Even though mangos are the most popular fruit in the world, they’re still considered new for some consumers. Our goal is to shift mangos from exotic to every day, and we’d love your help! That’s why we’ve created this retail dietitian toolkit, so you can help bring the world’s love of mangos to your shoppers. You’ll find loads of delicious ideas to inspire them to add more mangos to their cart, along with details on mango’s nutrition story to help your shoppers appreciate the health benefits, and tips on how to select and prepare mangos.