Promoting Cancon in the Age of New Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwestern Commission (Region A) Broadband Assessment

Southwestern Commission (Region A) Broadband Assessment Prepared by ECC Technologies, Inc. February 2018 Southwestern Commission Broadband Assessment Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................... pg. 4 1.1 Broadband Assessment Overview and Methodology .......................................... pg. 4 1.2 Results of Broadband Assessment ...................................................................... pg. 6 1.3 Next Steps – Further Analysis and Incorporation ................................................ pg. 7 2. Regional County Data ................................................................................. pg. 9 2.1 Residential Survey Questions and Responses ..................................................... pg. 9 2.2 Commercial Survey Questions and Responses .................................................. pg. 18 2.3 Respondent Map ............................................................................................. pg. 23 2.4 Speed Test Results ........................................................................................... pg. 23 3. Cherokee County Data .............................................................................. pg. 25 3.1 Residential Responses ...................................................................................... pg. 25 3.2 Commercial Responses .................................................................................... pg. 32 3.3 Provider Reported Availability vs. Speed -

J.R Beaudrie

J.R. BEAUDRIE Categories: People, Lawyers Gerald (J.R.) Beaudrie is a well-respected lawyer with expertise in all aspects of business law, and a practice focused on mergers and acquisitions and private equity. J.R. represents clients in a range of industries including technology, and the marketing and advertising sector. Providing guidance and assistance on general corporate commercial matters as well as transactions, J.R. advises on business structuring and organization, restructurings and reorganizations, mergers and acquisitions, and corporate finance, including private placements and credit facilities. He also works with his clients on the preparation and negotiation of contracts, agreements and corporate documents. With deep experience acting for professional service firms, clients trust J.R.’s thorough understanding of business law and his ability to navigate the complex laws and regulations that affect their companies and partnerships. Email: [email protected] Expertise: Business Law, Mergers & Acquisitions, Marketing & Advertising, Private Equity & Venture Capital, Technology Location: Toronto Phone: 416.307.4229 Position/Title: Partner, Business Law | Mergers & Acquisitions Education & Admissions: Degree: Called to the Ontario bar Year: 2006 ______ Degree: LLB University: University of Windsor Year: 2005 McMillan LLP | Vancouver | Calgary | Toronto | Ottawa | Montreal | Hong Kong | mcmillan.ca University: University of Detroit Mercy Year: 2005 ______ Degree: B.Comm. (Honours) University: University of Windsor Year: 2002 -

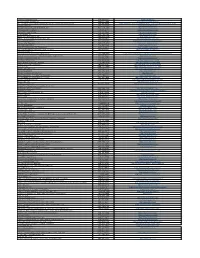

Complaints by Service Provider

Appendix A ‐ Complaints by Service Provider Complaints Change all % of % Concluded Resolved Closed Resolved Closed Accepted Issued Accepted Rejected Accepted Y/Y Provider Accepted and Concluded Complaint Pre‐Investigation Investigation Reco. Decisions #100 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 1010100 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 1010580 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 1010620 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 1010738 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 1011295.com 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 295.ca 0.00% 0 ‐100.0% 000000000 3Web 0.04% 4 ‐42.9% 550000000 450Tel 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 768812 Ontario Inc. 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 8COM 0.61% 69 ‐ 688126330000 A dimension humaine 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 Acanac Inc. 0.68% 77 ‐35.8% 79 42 3 28 51000 Access Communications Inc. 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 Achatplus Inc. 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 ACN Canada 0.66% 75 41.5% 70 50 5 11 40000 AEBC Internet Corporation 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 AEI Internet 0.04% 5 400.0% 310200000 AIC Global Communications 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 Alberta High Speed 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 Allstream inc. 0.04% 4 ‐ 431000000 Altima Telecom 0.02% 2 ‐ 110000000 America Tel 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 Amtelecom Telco GP Inc. 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 Auracom 0.02% 2 ‐ 210100000 Avenue 0.00% 0 ‐ 000000000 Axess Communications 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 Axsit 0.01% 1 ‐ 100100000 B2B2C Inc. 0.02% 2 ‐33.3% 320100000 Bell Aliant Regional Communications LP 1.41% 160 ‐1.2% 162 124 6 21 10 1000 Bell Canada 32.20% 3,652 ‐6.6% 3,521 2,089 235 889 307 0110 BlueTone Canada 0.03% 3 ‐ 311100000 BMI Internet 0.00% 0 0.0% 000000000 Bragg Communications Inc. -

Rogers Sportsnet PPV (Terrestrial and Direct-To-Home Services) – Licence Renewal

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2014-344 PDF version Route reference: 2014-151 Ottawa, 25 June 2014 Mountain Cablevision Limited and Fido Solutions Inc., partners in a general partnership carrying on business as Rogers Communications Partnership Across Canada Applications 2014-0021-7 and 2014-0022-5, received 10 January 2014 Rogers Sportsnet PPV (terrestrial and direct-to-home services) – Licence renewal The Commission renews the broadcasting licences for the national terrestrial pay-per- view service Rogers Sportsnet PPV and the national direct-to-home pay-per-view service Rogers Sportsnet PPV from 1 September 2014 to 31 August 2019. Applications 1. The Commission received two applications by Mountain Cablevision Limited and Fido Solutions Inc., partners in a general partnership carrying on business as Rogers Communications Partnership (Rogers) to renew the broadcasting licences for the national terrestrial pay-per-view service Rogers Sportsnet PPV and the national direct-to-home pay-per-view service Rogers Sportsnet PPV, which expire 31 August 2014. 2. The Commission received a comment from the Canadian Energy Efficiency Alliance (CEEA) with respect to these applications. The Commission considers that the comment by the CEEA, which deals with energy consumption by set-top boxes, falls outside the scope of this licence renewal proceeding. The public record for these applications can be found on the Commission’s website at www.crtc.gc.ca or by using the application numbers provided above. Non-compliance 3. Broadcasting Notice of Consultation 2014-151 stated that the licensee was in apparent non-compliance with its condition of licence related to closed captioning. As set out in Broadcasting Decisions 2005-83 and 2005-84, the licensee is required, by condition of licence, to provide closed captioning for not less than 90% of all programs aired during the broadcast year. -

Office Depot 12Th Anniversary Sweepstakes

TLC SEASON “DASH TO DOLLARS” SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. A PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. MUST BE 21 YEARS OF AGE OR OLDER AT THE TIME OF ENTRY TO ENTER OR WIN. OFFERED ONLY TO U.S. RESIDENTS OF THE 50 UNITED STATES, THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AND PUERTO RICO WHO ARE CURRENT SUBSCRIBERS IN GOOD STANDING TO ONE OF THE PROGRAMMING PROVIDERS LISTED IN SECTION 13. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED. 1. ELIGIBILITY: The TLC Season “Dash to Dollars” Sweepstakes (the “Sweepstakes”) Sweepstakes is open only to legal residents of the fifty (50) United States, the District of Columbia or Puerto Rico, who are 21 years of age or older as of the date of entry (the “Entrant”). Entrant must be a qualifying customer, in good standing, who is a current subscriber to select multichannel video programming distribution ("MVPD") providers (see Section 13 for a list of qualifying MVPD providers). Individuals must have access to the Internet in order to enter or win. Void outside of the fifty (50) United States, the District of Columbia or Puerto Rico, and where prohibited or restricted by law. Employees of Discovery Communications, LLC, (hereinafter known as the “Sponsor”) its respective affiliates, subsidiaries, advertising, production and promotion agencies, and the immediate families and members of the same household of each are not eligible. All federal, state, local and municipal laws and regulations apply. 2. TIMING: The Sweepstakes is scheduled from 12:00:00 am Eastern Time (“ET”) on November 28, 2016 and ends at 11:59:59 pm ET on December 12, 2016. -

Wireless Competition in Canada

Volume 7 • Issue 20 • August 2014 WIRELESS COMPETITION IN CANADA: DAMN THE TORPEDOES! THE TRIUMPH OF POLITICS OVER ECONOMICS† Jeffrey Church, Professor, Department of Economics and Director, Digital Economy Program, The School of Public Policy, University of Calgary Andrew Wilkins, Research Associate, Digital Economy Program, The School of Public Policy, University of Calgary SUMMARY Last year featured a high stakes battle between two mighty protagonists. On one side, allegedly representing the interests of all Canadians, the federal government. On the other side, Bell, Rogers, and Telus. The issue at stake: What institutions should govern the allocation of resources in the provision of wireless services? Should the outcomes — prices, quality, availability, and other terms of service — be determined by the market? Or should the government intervene? The answer to these questions should depend on the extent of competition and the ability of wireless providers to exercise inefficient market power — raise prices above their long run average cost of providing services. Do Bell, Rogers, and Telus exercise substantial inefficient market power? The accumulated wisdom of market economies is that state intervention inevitably is very costly, given asymmetries of information, uncertainty, and political pressure. At the very least the onus on those demanding and proposing government action is to provide robust evidence of the substantial exercise of inefficient market power. This paper is a contribution to the ongoing debate regarding the existence and extent of market power in the provision of wireless services in Canada. The conventional wisdom that competition in wireless services was insufficient was challenged by our earlier School of Public Policy paper.†† In that study we demonstrated that the Canadian wireless sector was sufficiently competitive. -

Avis De Consultation De Télécom CRTC 2011-596

Avis de consultation de télécom CRTC 2011-596 Version PDF Ottawa, le 19 septembre 2011 Appel aux observations sur une condition révisée qui s’appliquerait aux entreprises canadiennes qui offrent des services aux fournisseurs de services VoIP locaux Numéro de dossier : 8663-C12-201112820 Contexte 1. Dans la décision de télécom 2005-21, le Conseil a exigé que les fournisseurs de services de communication vocale sur protocole Internet (VoIP) locaux offrent le service 9-1-1 et il leur a imposé des obligations connexes. Dans les décisions de télécom 2005-61 et 2007-44 ainsi que dans la politique réglementaire de télécom 2011-426, le Conseil a modifié les obligations existantes relatives au service 9-1-1 et il en a imposé de nouvelles aux fournisseurs de services VoIP locaux. Une liste complète des obligations relatives au service 9-1-1 qui s’appliquent aux fournisseurs de services VoIP locaux figure en annexe. 2. Les obligations relatives au service 9-1-1 énoncées dans les décisions de télécom 2005-21, 2005-61 et 2007-44 ainsi que dans la politique réglementaire de télécom 2011-426 sont imposées aux revendeurs de services VoIP en vertu d’une disposition qui prévoit que, pour fournir des services de télécommunication aux fournisseurs de services VoIP locaux, les entreprises canadiennes doivent exiger dans leurs contrats de service ou leurs autres arrangements avec ces fournisseurs que ces derniers respectent les obligations relatives au service 9-1-1 (une « condition contractuelle »). Si un fournisseur de services VoIP locaux ne respecte pas les obligations relatives au service 9-1-1, le Conseil peut amorcer une instance en vue de justifier pourquoi l’entreprise canadienne ou tout autre fournisseur de services de télécommunication qui fournit des services de télécommunication au fournisseur de services VoIP locaux ne devrait pas être tenu de cesser de lui fournir ces services. -

SEC Network Affiliates 020620.Pdf

3 Rivers Communications 800-796-4567 https://3rivers.net/ Access Cable Television Inc 606-677-2444 https://www.accesshsd.com/ Ace Telephone Associations (aka AcenTek & Ace Communications Group) 888-404-4940 https://www.acentek.net/2014/09/15/ace-communications-is-now-acentek/ Adams CATV, Inc (888) 222-0077 https://adamscable.com/ ADVANCED SATELLITE SYSTEMS, INC. (501) 835-3474 https://disharkansas.com/ Albany Mutual Telephone 320.845.2101 https://www.albanytel.com/ Algona Municipal Utilities 515.295.3584 http://www.netamu.com/ All West/Utah, Inc. (435) 783-4361 http://www.allwest.com/ Allen's TV Cable Service, Inc. (985) 384-8335 http://www.atvc.net/ Alliance Communications Cooperative, Inc 605-594-3411 https://www.alliancecom.net/ Allo Communications 844-560-2556 https://www.allocommunications.com/ Alpine Cable Television, L.C. (800) 635-1059 https://www.alpinecom.net/ Alta Municipal Utilities 712-200-1122 https://www.alta-tec.net/ Amarillo Wireless dba AW Broadband 806-316-5071 https://amarillowireless.net/ American Broadband (fka Huntel Systems, Inc.) 888-262-2661 https://www.abbnebraska.com/ American Cable TV Americas Center Corporation-Holding,LLC (618) 257-3750 https://www.manta.com/c/mtbzdpz/americas-center-corporation Applied Communications Technolgy/Arapahoe Cable TV Inc 888 565-5422 http://www.atcjet.net/ Arkwest Communications, Inc. 479-495-4200 http://www.arkwest.com/ Armstrong Utilities, Inc. (724) 283-0925 http://www.agoc.com/Contact Arthur Mutual Telephone Company (419) 393-2233 http://www.artelco.net/index.php Ashland Home Net Corporation 541-488-9207 http://ashlandhome.net/Default.asp AT&T U-verse (800) 331-0500 https://www.att.com/tv/u-verse.html Atkins Cablevision, Inc. -

A North American Perspective

Influence of Copyright on the Emergence of New Technologies: a North American Perspective A thesis submitted to the Facuky of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillrnent of the requirements of the degree of master. Me MarbHel6ne Deschamps-Maquis FacultyofLaw McGill University, Montreal November 1999 O Marie-HBldne Deschamps-Maquis, 1999 National Library Biblioîhèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions el Bibliographie Services senhces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 345. Na WaiIigion Onawa ON KlA ON4 WONK1AW CMada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exciusive Iicence allowing the exchishe permettant à la National Lr'brary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fonnats. la fome de microfiche/fh, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conseme la propriété du copyright in tûis thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial exiracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de ceiie-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. 2. TE€ ESSENCE OF COPYRIGHT ---..,. 1 1. CONCLUSION ,.-.-.-.!H Ce mémoire de maitrise étudie l'impact du droit d'auteur Nord Américain sur i'évolution technologique. Sa prerniin partie propose une vision large du droit d'auteur englobant la &alité canadienne et américaine. Suite à l'étude des différentes définitions légales de œ concept, de son origine et de ses justifications sous-jacentes, se construit une définition englobante du droit d'auteur en Amérique du Nord. -

Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2008-100

Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2008-100 Ottawa, 30 October 2008 Regulatory policy Regulatory frameworks for broadcasting distribution undertakings and discretionary programming services Table of contents Paragraph Summary Introduction 1 Background 5 The Canadian broadcasting system 11 Need for a new regulatory framework 27 Calibrating the role of broadcasting distribution undertakings and the 30 programming sector Key elements of the Call for comments 34 Regulatory framework for broadcasting distribution undertakings 35 Basic service – Terrestrial broadcasting distribution undertakings 36 Basic service – Direct-to-home undertakings 46 Access rules for Canadian programming services 60 Access rules for high definition pay and specialty services 74 Access rules for minority-language services 80 Access rules for unrelated Category B, exempt and pay audio services 87 Preponderance of Canadian programming services 95 Packaging requirements 103 Third-language services distributed by broadcasting distribution 129 undertakings New forms of advertising available to broadcasting distribution 139 undertakings Advertising in local availabilities of non-Canadian services 144 Issues relating to dispute resolution 154 Signal sourcing and transport 169 Licence classes and exemptions for broadcasting distribution 187 undertakings Other issues relating to broadcasting distribution undertakings 202 Regulatory framework for pay and specialty programming undertakings 235 Authorization of non-Canadian services 239 Genre exclusivity – Canadian services 250 -

Liste Des Fournisseurs Pour Les Perceptions De Comptes

Liste des fournisseurs pour les Perceptions de Comptes A A. & B SOUND A.B. TREASURY A.R.C. ACCOUNTS RECOVERY OPERATION A.R.C. ACCOUNTS RECOVERY CORPORATION ABBOTSFORD (CITY OF) ABC BENEFITS CORPORATION ABLE CABLEVISION LTD ACC LONG DISTANCE LTD. ACCESS CABLE TELEVISION LTD - B/S LTD ACCESS CABLE TELEVISION LTD. ACCESS COMMUNICATION ACCESS COMMUNICATIONS INC. ACN CANADA ACTON VALE, VILLE DE ADAM, W.H. ADRIATIC FUEL OIL CO. LTD. ADVENTURE ELECTRONICS INC. AETNA CANADA-MARITIME LIFE AETNA LIFE INS. CO. AETNA LIFE INS. CO. OF CANADA AFFINITY CARD (CARTE AFFINITÉ) AFFILIATED MEMBER CARD (CARTE MEMBRE AFFILIÉ). AGENCE DE RECOUVREMENT COLL-BEC LTÉE AGLINE (TORONTO, MONTREAL AND HALIFAX PROCESSING CENTRES) AGLINE, THE CHARGE ACCOUNT FOR RURAL CANADA AGRICARD AGRICORE AGRICORE COOPERATIVE LTD AGRICORP AGRICORP / CROP INSURANCE AGRICULTURE FINANCIAL SERVICES CORP. AIC ASIA INTERNATIONAL SERVICES CORP (ALBERTA) (UTILITY) AIC ASIA INTERNATIONAL SERVICES CORP. AIRWAY SURGICAL APPLIANCES LTD/LTEE AJAX HYDRO ELECTRIC COMMISSSION ALARME CONCORDE INC. ALARME DE LA CAPITALE (1992) INC. ALARME TÉLÉTRONIC INC. ALBERT VANLOON ALBERTA (PROVINCE OF) (CORP. TAX HOTEL AND ROOM) ALBERTA (PROVINCE OF) (MAINTENANCE ENFORCEMENT - CHILD SUPPORT PAYMENTS) ALBERTA (PROVINCE OF) (RURAL ELECTRIFICATION) ALBERTA BLUE CROSS ALBERTA FUEL OIL/ALBERTA TRIDENT ALBERTA HEALTH CARE INSURANCE PLAN ALBERTA WHEAT POOL ALEXANDRIA CABLEVISION ALFRED/PLANTAGENET CABLEVISION ALL COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK OF CANADA CO. ALLIANCE MUTUEL-VIE/MUT.LIFE ALLSTATE ALLSTATE (TAXES) ALMONTE HYDRO ALTAGAS UTILITIES INC AMALGAMATED COLLECTION SERVICES INC. AMEX BANK OF CANADA (AMERICAN EXPRESS) AMHERSTBURG HYDRO-ELECTRIC COMMISSION AMOS (VILLE D') AMTELECOM COMMUNICATIONS (CABLE TV / TELECOMMUNICATION) ANAESTHESIA MANAGEMENT INC. ANCASTER (CORPORATION OF THE TOWN OF) ANCASTER HYDRO-ELECTRIC COMMISSION ANDERSON FUELS ULTRACOMFORT ANGLIN FUELS ANJOU (VILLE D') ANNAPOLIS COUNTY (MUNICIPALITY OF) ANTHONY INSURANCE INC APPAREILS ÉLECTRONIQUES BÉRUBÉ INC. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2013-583

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2013-583 PDF version Route reference: 2013-335 Ottawa, 31 October 2013 Rogers Communications Inc., on behalf of Mountain Cablevision Limited Across Canada Application 2013-0906-3, received 20 June 2013 Public hearing in the National Capital Region 12 September 2013 Terrestrial broadcasting distribution undertakings serving various locations in Ontario, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador; national video-on-demand programming undertaking known as Rogers On Demand; and terrestrial and direct-to-home national pay-per-view services known as Rogers Sportsnet – Acquisition of assets (Corporate reorganization) The Commission denies the application by Rogers Communications Inc. on behalf of Mountain Cablevision Limited for authority to acquire from Rogers Communications Partnership its terrestrial broadcasting distribution undertakings serving various locations in Ontario, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, its national video-on-demand programming undertaking known as Rogers On Demand and its terrestrial and direct-to-home national pay-per-view services, both known as Rogers Sportsnet. The Commission is concerned that the proposal to separate the broadcasting assets from the licences and to grant operational control of the undertakings to an entity that is not the licensee for an indeterminate period of time would set an inappropriate precedent that would adversely impact the Commission’s ability to supervise and regulate the broadcasting system in accordance with its mandate, including ensuring the proper application of orders from the Governor in Council, such as the Direction to the CRTC (Ineligibility of Non-Canadians) and the Direction to the CRTC (Ineligibility to Hold Broadcasting Licences). The application 1. Rogers Communications Inc.