A New Venture in Corpus-Based Lexicography: Towards a Dictionary of Academic English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexical Ambiguity • Syntactic Ambiguity • Semantic Ambiguity • Pragmatic Ambiguity

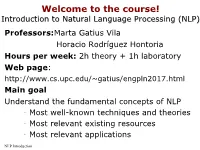

Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing (NLP)(NLP) Professors:Marta Gatius Vila Horacio Rodríguez Hontoria Hours per week: 2h theory + 1h laboratory Web page: http://www.cs.upc.edu/~gatius/engpln2017.html Main goal Understand the fundamental concepts of NLP • Most well-known techniques and theories • Most relevant existing resources • Most relevant applications NLP Introduction 1 Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing Content 1. Introduction to Language Processing 2. Applications. 3. Language models. 4. Morphology and lexicons. 5. Syntactic processing. 6. Semantic and pragmatic processing. 7. Generation NLP Introduction 2 Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing Assesment • Exams Mid-term exam- November End-of-term exam – Final exams period- all the course contents • Development of 2 Programs – Groups of two or three students Course grade = maximum ( midterm exam*0.15 + final exam*0.45, final exam * 0.6) + assigments *0.4 NLP Introduction 3 Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing Related (or the same) disciplines: •Computational Linguistics, CL •Natural Language Processing, NLP •Linguistic Engineering, LE •Human Language Technology, HLT NLP Introduction 4 Linguistic Engineering (LE) • LE consists of the application of linguistic knowledge to the development of computer systems able to recognize, understand, interpretate and generate human language in all its forms. • LE includes: • Formal models (representations of knowledge of language at the different levels) • Theories and algorithms • Techniques and tools • Resources (Lingware) • Applications NLP Introduction 5 Linguistic knowledge levels – Phonetics and phonology. Language models – Morphology: Meaningful components of words. Lexicon doors is plural – Syntax: Structural relationships between words. -

Conference Abstracts

EIGHTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Held under the Patronage of Ms Neelie Kroes, Vice-President of the European Commission, Digital Agenda Commissioner MAY 23-24-25, 2012 ISTANBUL LÜTFI KIRDAR CONVENTION & EXHIBITION CENTRE ISTANBUL, TURKEY CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS Editors: Nicoletta Calzolari (Conference Chair), Khalid Choukri, Thierry Declerck, Mehmet Uğur Doğan, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Asuncion Moreno, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis. Assistant Editors: Hélène Mazo, Sara Goggi, Olivier Hamon © ELRA – European Language Resources Association. All rights reserved. LREC 2012, EIGHTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Title: LREC 2012 Conference Abstracts Distributed by: ELRA – European Language Resources Association 55-57, rue Brillat Savarin 75013 Paris France Tel.: +33 1 43 13 33 33 Fax: +33 1 43 13 33 30 www.elra.info and www.elda.org Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Copyright by the European Language Resources Association ISBN 978-2-9517408-7-7 EAN 9782951740877 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the prior permission of the European Language Resources Association ii Introduction of the Conference Chair Nicoletta Calzolari I wish first to express to Ms Neelie Kroes, Vice-President of the European Commission, Digital agenda Commissioner, the gratitude of the Program Committee and of all LREC participants for her Distinguished Patronage of LREC 2012. Even if every time I feel we have reached the top, this 8th LREC is continuing the tradition of breaking previous records: this edition we received 1013 submissions and have accepted 697 papers, after reviewing by the impressive number of 715 colleagues. -

Corpus Linguistics: a Practical Introduction

Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Introduction Nadja Nesselhauf, October 2005 (last updated September 2011) 1) Corpus Linguistics and Corpora - What is corpus linguistics (I)? - What data do linguists use to investigate linguistic phenomena? - What is a corpus? - What is corpus linguistics (II)? - What corpora are there? - What corpora are available to students of English at the University of Heidelberg? (For a list of corpora available at the Department of English click here) 2) Corpus Software - What software is there to perform linguistic analyses on the basis of corpora? - What can the software do? - A brief introduction to an online search facility (BNC) - A step-to-step introduction to WordSmith Tools 3) Exercises (I and II) - I Using the WordList function of WordSmith - II Using the Concord function of WordSmith 4) How to conduct linguistic analyses on the basis of corpora: two examples - Example 1: Australian English vocabulary - Example 2: Present perfect and simple past in British and American English - What you have to take into account when performing a corpuslingustic analysis 5) Exercises (III) - Exercise III.1 - Exercise III.2 6) Where to find further information on corpus linguistics 1) Corpus Linguistics and Corpora What is corpus linguistics (I)? Corpus linguistics is a method of carrying out linguistic analyses. As it can be used for the investigation of many kinds of linguistic questions and as it has been shown to have the potential to yield highly interesting, fundamental, and often surprising new insights about language, it has become one of the most wide-spread methods of linguistic investigation in recent years. -

Compilación De Un Corpus De Habla Espontánea De Chino Putonghua Para Su Aplicación En La Enseñanza Como Lengua Segunda a Hispanohablantes

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Departamento de Lingüística General, Lenguas Modernas, Lógica y Filosofía de la Ciencia, Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada Laboratorio de Lingüística Informática Compilación de un corpus de habla espontánea de chino putonghua para su aplicación en la enseñanza como lengua segunda a hispanohablantes DONG Yang Tesis doctoral dirigida por el Dr. Antonio Moreno Sandoval 2011 Agradecimientos Agradecimientos En primer lugar, quisiera dar las gracias al director de esta tesis, Dr. Antonio Moreno Sandoval, especialmente por aceptarme para realizar esta tesis bajo su dirección. Además, quisiera agradecer la confianza y paciencia que él ha depositado en este trabajo, así como su constante estímulo, sus comentarios y consejos tan valiosos para mi tesis. Gracias a la beca concedida por la Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional, he podido seguir mis estudios del Programa de Doctorado en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid y dedicarme totalmente a la tesis. A la Dra. Taciana Fisac, coordinadora del Programa de Doctorado “España y Latinoamérica Contemporáneas” y catedrática del Centro de Estudios de Asia Oriental de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, quiero extenderle un sincero agradecimiento por su disponibilidad, generosidad y ayuda incondicional en todo momento. Fue ella quien organizó y promovió este Programa de Doctorado de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, con la colaboración de la Universidad de Lenguas Extranjeras de Beijing. Quisiera agradecer a los miembros del Laboratorio de Lingüística Informática de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid por la ayuda que me han ofrecido durante estos años de aprendizaje. Se trata de un soporte profesional muy importante. -

Concreteness 25 3.1 Introduction

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/93581 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-28 and may be subject to change. Making choices Modelling the English dative alternation c 2012 by Daphne Theijssen Cover photos by Harm Lourenssen ISBN 978-94-6191-275-6 Making choices Modelling the English dative alternation Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S.C.J.J. Kortmann, volgens besluit van het college van decanen, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 18 juni 2012 om 13.30 uur precies door Daphne Louise Theijssen geboren op 25 juni 1984 te Uden Promotor: Prof. dr. L.W.J. Boves Copromotoren: Dr. B.J.M. van Halteren Dr. N.H.J. Oostdijk Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. Dr. A.P.J. van den Bosch Prof. Dr. R.H. Baayen (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Germany & University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada) Dr. G. Bouma (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) Nobody said it was easy It’s such a shame for us to part Nobody said it was easy No one ever said it would be this hard Oh take me back to the start I was just guessing at numbers and figures Pulling your puzzles apart Questions of science; science and progress Do not speak as loud as my heart The Scientist – Coldplay Dankwoord / Acknowledgements Wanneer ik mensen vertel dat ik een proefschrift heb geschreven, kijken ze me vaak vol bewondering aan. -

8Th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation 2012

8th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation 2012 (LREC-2012) Istanbul, Turkey 21-27 May 2012 Volume 1 of 5 ISBN: 978-1-62276-504-1 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2012) by the Association for Computational Linguistics All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2012) For permission requests, please contact the Association for Computational Linguistics at the address below. Association for Computational Linguistics 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania 18360 Phone: 1-570-476-8006 Fax: 1-570-476-0860 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2634 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 PaCo2: A Fully Automated Tool for Gathering Parallel Corpora from the Web .......................................................................................1 Iñaki San Vicente, Iker Manterola Terra: A Collection of Translation Error-Annotated Corpora ....................................................................................................................7 Mark Fishel, Ondrej Bojar, Maja Popovic A Light Way to Collect Comparable Corpora from the Web .....................................................................................................................15 -

Papers Index

Papers Index SESSION O1 - Corpora for Machine Translation I˜naki San Vicente and Iker Manterola, PaCo2: A Fully Automated tool for gathering Parallel Corpora from the Web.................................. ........................................ 1 Mark Fishel, Ondˇrej Bojar and Maja Popovi´c, Terra: a Collection of Translation Error- Annotated Corpora................................... .......................................... 7 Ahmet Aker, Evangelos Kanoulas and Robert Gaizauskas, A light way to collect comparable corpora from the Web.................................. ........................................ 15 Volha Petukhova, Rodrigo Agerri, Mark Fishel, Sergio Penkale, Arantza del Pozo, Mir- jam Sepesy Maucec, Andy Way, Panayota Georgakopoulou and Martin Volk, SUMAT: Data Collection and Parallel Corpus Compilation for Machine Translation of Subtitles.......... 21 Daniele Pighin, Llu´ıs M`arquez and Llu´ıs Formiga, The FAUST Corpus of Adequacy Assess- ments for Real-World Machine Translation Output . ............................... 29 SESSION O2 - Infrastructures and Strategies for LRs (1) Stelios Piperidis, The META-SHARE Language Resources Sharing Infrastructure: Principles, Challenges, Solutions ................................... ....................................... 36 Riccardo Del Gratta, Francesca Frontini, Francesco Rubino, Irene Russo and Nicoletta Calzolari, The Language Library: supporting community effort for collective resource production 43 Khalid Choukri, Victoria Arranz, Olivier Hamon and Jungyeul Park, Using the Interna- -

The Prime Machine: a User-Friendly Corpus Tool for English Language Teaching and Self-Tutoring Based on the Lexical Priming Theory of Language

The Prime Machine: A user-friendly corpus tool for English language teaching and self-tutoring based on the Lexical Priming theory of language Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Stephen Jeaco. June 2015 Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................... 7 List of Tables .......................................................................................................................... 15 List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 19 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 21 List of conference presentations arising from this project .................................................... 23 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 24 Chapter 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................... 25 1.1 Research questions ...................................................................................................... 26 1.2 Structure ...................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 2: Survey of Students and Teachers ........................................................................ -

Unit 3: Available Corpora and Software

Corpus building and investigation for the Humanities: An on-line information pack about corpus investigation techniques for the Humanities Unit 3: Available corpora and software Irina Dahlmann, University of Nottingham 3.1 Commonly-used reference corpora and how to find them This section provides an overview of commonly-used and readily available corpora. It is also intended as a summary only and is far from exhaustive, but should prove useful as a starting point to see what kinds of corpora are available. The Corpora here are divided into the following categories: • Corpora of General English • Monitor corpora • Corpora of Spoken English • Corpora of Academic English • Corpora of Professional English • Corpora of Learner English (First and Second Language Acquisition) • Historical (Diachronic) Corpora of English • Corpora in other languages • Parallel Corpora/Multilingual Corpora Each entry contains the name of the corpus and a hyperlink where further information is available. All the information was accurate at the time of writing but the information is subject to change and further web searches may be required. Corpora of General English The American National Corpus http://www.americannationalcorpus.org/ Size: The first release contains 11.5 million words. The final release will contain 100 million words. Content: Written and Spoken American English. Access/Cost: The second release is available from the Linguistic Data Consortium (http://projects.ldc.upenn.edu/ANC/) for $75. The British National Corpus http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/ Size: 100 million words. Content: Written (90%) and Spoken (10%) British English. Access/Cost: The BNC World Edition is available as both a CD-ROM or via online subscription. -

Lexical Selection and the Evolution of Language Units

Open Linguistics 2015; 1: 458–466 Research Article Open Access Glenn Hadikin Lexical selection and the evolution of language units DOI 10.1515/opli-2015-0013 Received September 15, 2014; accepted May 27, 2015 Abstract: In this paper I discuss similarities and differences between a potential new model of language development - lexical selection, and its biological equivalent - natural selection. Based on Dawkins' (1976) concept of the meme I discuss two units of language and explore their potential to be seen as linguistic replicators. The central discussion revolves around two key parts - the units that could potentially play the role of replicators in a lexical selection system and a visual representation of the model proposed. draw on work by Hoey (2005), Wray (2008) and Sinclair (1996, 1998) for the theoretical basis; Croft (2000) is highlighted as a similar framework. Finally brief examples are taken from the free online corpora provided by the corpus analysis tool Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff, Rychly, Smrz and Tugwell 2004) to ground the discussion in real world communicative situations. The examples highlight the point that different situational contexts will allow for different units to flourish based on the local social and linguistic environment. The paper also shows how a close look at the specific context and strings available to a language user at any given moment has potential to illuminate different aspects of language when compared with a more abstract approach. Keywords: memes, natural selection, lexical priming, needs only analysis, NOA, lexical unit, lexical selection, linguemes 1 Introduction In 1976 Richard Dawkins changed the way many look at biological evolution with his popular account of a gene’s eye view of natural selection – The Selfish Gene. -

The Spoken British National Corpus 2014

The Spoken British National Corpus 2014 Design, compilation and analysis ROBBIE LOVE ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science Department of Linguistics and English Language Lancaster University A thesis submitted to Lancaster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics September 2017 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................. i Abstract ............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... vi List of tables .................................................................................................. viii List of figures .................................................................................................... x 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Research aims & structure ....................................................................................................... 3 2 Literature review ........................................................................................ 6 2.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. -

The Learner Corpora of Spoken English: What Has Been Done and What Should Be Done? Soyeon Yoon† Incheon National University

The Learner Corpora of Spoken English: What Has Been Done and What Should Be Done? Soyeon Yoon† Incheon National University ABSTRACT The number of spoken learner corpora is smaller than that of written corpora; however, demand for spoken corpora has continuously increased. This study investigates the current state of spoken English-language learner corpora both in the world and in Korea, with a focus on their size, speakers, and genres. Based on this survey, the study discusses factors to consider when building and publishing a spoken learner corpus, especially with respect to the issues of conversation genre, proficiency level, and annotation. Keywords: spoken corpus, learner corpus, conversation, transcription, annotation 1. Introduction Ever since Brown Corpus was constructed in 1967, various types and sizes of corpora have been constructed and widely used as quantitative and qualitative evidence not only for language research but also for foreign/second language education. In language education, the corpora of native language have served as reference that the learners’ language patterns can be compared to or as a model that the learners pursue. On the other hand, learner corpora collect second or foreign language data that the learners use in either written or spoken forms. They have been constructed to examine learners’ linguistic knowledge and how their usage patterns differ from those of native speakers or differ depending on the learners’ age, gender, first language, and fluency. According to Center for English Corpus Linguistics1) (CECL) at Universite Catholique de Louvain, there are 177 learner corpora in the world currently available. Only 40 of them contain spoken data while most are written corpora.