The History of the Sacred Purple: the Use of Muricidae As a Dye Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

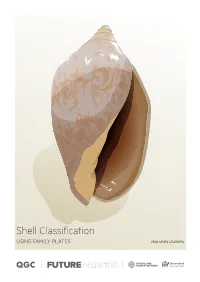

Shell Classification – Using Family Plates

Shell Classification USING FAMILY PLATES YEAR SEVEN STUDENTS Introduction In the following activity you and your class can use the same techniques as Queensland Museum The Queensland Museum Network has about scientists to classify organisms. 2.5 million biological specimens, and these items form the Biodiversity collections. Most specimens are from Activity: Identifying Queensland shells by family. Queensland’s terrestrial and marine provinces, but These 20 plates show common Queensland shells some are from adjacent Indo-Pacific regions. A smaller from 38 different families, and can be used for a range number of exotic species have also been acquired for of activities both in and outside the classroom. comparative purposes. The collection steadily grows Possible uses of this resource include: as our inventory of the region’s natural resources becomes more comprehensive. • students finding shells and identifying what family they belong to This collection helps scientists: • students determining what features shells in each • identify and name species family share • understand biodiversity in Australia and around • students comparing families to see how they differ. the world All shells shown on the following plates are from the • study evolution, connectivity and dispersal Queensland Museum Biodiversity Collection. throughout the Indo-Pacific • keep track of invasive and exotic species. Many of the scientists who work at the Museum specialise in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species. In fact, Queensland Museum scientists -

The Recent Molluscan Marine Fauna of the Islas Galápagos

THE FESTIVUS ISSN 0738-9388 A publication of the San Diego Shell Club Volume XXIX December 4, 1997 Supplement The Recent Molluscan Marine Fauna of the Islas Galapagos Kirstie L. Kaiser Vol. XXIX: Supplement THE FESTIVUS Page i THE RECENT MOLLUSCAN MARINE FAUNA OF THE ISLAS GALApAGOS KIRSTIE L. KAISER Museum Associate, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA 4 December 1997 SiL jo Cover: Adapted from a painting by John Chancellor - H.M.S. Beagle in the Galapagos. “This reproduction is gifi from a Fine Art Limited Edition published by Alexander Gallery Publications Limited, Bristol, England.” Anon, QU Lf a - ‘S” / ^ ^ 1 Vol. XXIX Supplement THE FESTIVUS Page iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 MATERIALS AND METHODS 1 DISCUSSION 2 RESULTS 2 Table 1: Deep-Water Species 3 Table 2: Additions to the verified species list of Finet (1994b) 4 Table 3: Species listed as endemic by Finet (1994b) which are no longer restricted to the Galapagos .... 6 Table 4: Summary of annotated checklist of Galapagan mollusks 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 6 LITERATURE CITED 7 APPENDIX 1: ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF GALAPAGAN MOLLUSKS 17 APPENDIX 2: REJECTED SPECIES 47 INDEX TO TAXA 57 Vol. XXIX: Supplement THE FESTIVUS Page 1 THE RECENT MOLLUSCAN MARINE EAUNA OE THE ISLAS GALAPAGOS KIRSTIE L. KAISER' Museum Associate, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA Introduction marine mollusks (Appendix 2). The first list includes The marine mollusks of the Galapagos are of additional earlier citations, recent reported citings, interest to those who study eastern Pacific mollusks, taxonomic changes and confirmations of 31 species particularly because the Archipelago is far enough from previously listed as doubtful. -

An Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Of

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (2), Serial No. 29, April, 2013:350-370 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.7i2.22 Adire in South-western Nigeria: Geography of the Centres Areo, Margaret Olugbemisola- Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] & Kalilu, Razaq Olatunde Rom - Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] Abstract Adire, the patterned dyed cloth is extant and is practiced in almost all Yoruba towns in Southwestern Nigeria. The art tradition is however preponderant in a few Yoruba towns to the extent that the names of these towns are traditionally inseparable with the Adire art tradition. With Western education, introduction of foreign religions, influence from other cultures, technique and technology, there is a shift in the producers of Adire, the training pattern, and even an evolution in the production centre. While Western education resulted in a shift from the hitherto traditional Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 350 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (2) Serial No. 29, April, 2013 Pp.350-370 apprenticeship method to the study of the art in schools, unemployment gave birth to the introduction of training drives by government and non governmental parastatals. This study, a field research, is an appraisal of the factors that contributed to the vibrancy of the traditionally renowned centres, and how the newly evolved centres have in contemporary times contributed to the sustainability of the Adire art tradition. -

Bruno Sabelli * E Stefano Tommasini * Introduzione

Boll. Malacologico I Milano' 18 I (9-12) I 291-300 I settembre-dicembre 1982 Bruno Sabelli * e Stefano Tommasini * OSSERVAZIONI SULLA RADULA E SULLA PROTOCONCA DI BOLINUS BRANDARIS (L" 1758) E PHYLWNOTUS TRUNCULUS (L" 1758) Introduzione La sottofamiglia M u r i c i n a e comprende in Mediterraneo so- lo poche specie, per la precisione sei, di cui una (Bolinus cornutus (L., 1758)) segnalata solo dubitativamente per il nostro mare, due (Mu- rex tribulus L., 1758 e Aspella anceps (LAMARCK,1822)) sono ospiti re- centissimi essendo penetrati e forse acclimatati si in Mediterraneo so- lo dopo l'apertura del canale di Suez (BARASHe DANIN, 1972, 1977; GHI- SOTTI,1974) mentre le altre tre si possono definire come autoctone. Poichè le tre specie esotiche sono state reperite solo in numero esi- guo di esemplari e comunque mai viventi non si hanno informazioni sulla loro radula e sulla microscultura della loro protoconca e noi non siamo stati in grado di colmare questa lacuna. Per quanto con- cerne le altre tre specie Dermomurex scalaroides (BLAINVILLE,1826) è stato ampiamente investigato sotto il profilo tassonomico da FRAN- CHINI (1977) che ne ha anche illustrato la radula; mancherebbero co- munque dati sulla sua protoconca, ma gli oltre trenta esemplari esa- minati di questa specie non si sono prestati per questo studio essen- do tutti con l'apice abraso per cui la questione rimane insoluta. Solo le ultime due specie: Bolinus brandaris (L., 1758) e Phyllonotus trun- culus (L., 1758), sono dunque state studiate e se pur poco rappresen- tative dell'intera sottofamiglia presentano comunque alcuni interes- santi problemi che ci hanno indotto a redigere questa nota. -

Mollusks of Manuel Antonio National Park, Pacific Costa Rica

Rev. Biol. Trop. 49. Supl. 2: 25-36, 2001 www.rbt.ac.cr, www.ucr.ac.cr Mollusks of Manuel Antonio National Park, Pacific Costa Rica Samuel Willis 1 and Jorge Cortés 2-3 1140 East Middle Street, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 17325, USA. 2Centro de Investigación en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (CIMAR), Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. FAX: (506) 207-3280. E-mail: [email protected] 3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. (Received 14-VII-2000. Corrected 23-III-2001. Accepted 11-V-2001) Abstract: The mollusks in Manuel Antonio National Park on the central section of the Pacific coast of Costa Rica were studied along thirty-six transects done perpendicular to the shore, and by random sampling of subtidal environments, beaches and mangrove forest. Seventy-four species of mollusks belonging to three classes and 40 families were found: 63 gastropods, 9 bivalves and 2 chitons, during this study in 1995. Of these, 16 species were found only as empty shells (11) or inhabited by hermit crabs (5). Forty-eight species were found at only one locality. Half the species were found at one site, Puerto Escondido. The most diverse habitat was the low rocky intertidal zone. Nodilittorina modesta was present in 34 transects and Nerita scabricosta in 30. Nodilittorina aspera had the highest density of mollusks in the transects. Only four transects did not clustered into the four main groups. The species composition of one cluster of transects is associated with a boulder substrate, while another cluster of transects associates with site. -

Cariotipos De Los Caracoles De Tinte Plicopurpura Pansa Y Plicopurpura Columellaris (Gastropoda: Muricidae)

Cariotipos de los caracoles de tinte Plicopurpura pansa y Plicopurpura columellaris (Gastropoda: Muricidae) Lenin Arias-Rodriguez1,3, Juan P. González-Hermoso2, Horacio Fletes-Regalado2, Luz Estela Rodríguez-Ibarra1 & Gabriela Del Valle Pignataro1 1 Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A.C. Unidad, Mazatlán, Sábalo-Cerritos S/N Estero del Yugo, A.P. 711, Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México. Tel. (669) 989-87-00. Fax (669) 989-87-01; [email protected] 2 Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit, Facultad de Ingeniería Pesquera, Bahia de Matanchan, Km 12, Carretera los Cocos, A.P. 10, San Blas Nayarit, Mexico. Tel/Fax. (323) 31-21-20. 3 División Académica de Ciencias Biológicas, UJAT. Carretera Villahermosa-Cárdenas Km 0.5 S/N. Entronque a Bosques de Saloya. C.P. 86150. Tel. (993) 354-4308. Villahermosa, Tabasco, México. Recibido 04-III-2006. Corregido 11-XII-2006. Aceptado 14-V-2007. Abstract: Karyotypes of the purple snails Plicopurpura pansa and Plicopurpura columellaris (Gastropoda: Muricidae). The karyotypes of the purple snails Plicopurpura pansa (Gould, 1853) and P. columellaris (Lamarck, 1816) were established from 17 and 13 adults, respectively; and from eight capsules with embryos of P. pansa. In P. pansa were counted 59 mitotic fields in the adults and 127 in embryos; and 118 fields in P. columellaris. Chromosome numbers from 30 to 42 were observed in both species. Such a variation was notori- ous in each sample and there was no evidence of any relationship with tissue (gill, muscle and stomach). Both species has a typical modal number of 2n=36 chromosomes. Five good quality chromosome spreads were selected from adults of each species to assemble the karyotype. -

The ISCC-NBS Method of Designating Colors and a Dictionary of Color Names

Uc 8 , .Department of Commerce Na Canal Bureau of Standards Circular UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE • Sinclair Weeks, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS • A. V. Astin, Director The ISCC-NBS Method of Designating Colors and a Dictionary of Color Names National Bureau of Standards Circular 553 Issued November 1, 1955 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. Price 32 7 1 National Bureau of Standards NOV 1 1955 8 (0*118 QC 00 U555 Cop. 1 Preface I^Ever since the language of man began to develop, words or expressions have been used first to indicate and then to describe colors. Some of these have per- sisted throughout the centuries and are those which refer to the simple colors or ranges such as red or yellow. As the language developed, more and more color names were invented to describe the colors used by art and industry and in late years in the rapidly expanding field of sales promotion. Some of these refer to the pigment or dye used, as Ochre Red or Cochineal, or a geographical location of its source such as Naples Yellow or Byzantium. Later when it became clear that most colors are bought by or for women, many color names indicative of the beauties and wiles of the fan- sex were introduced, as French Nude, Heart’s Desire, Intimate Mood, or Vamp. Fanciful color names came into vogue such as Dream Fluff, Happy Day, Pearly Gates, and Wafted Feather. Do not suppose that these names are without economic importance for a dark reddish gray hat for Milady might be a best seller ; if advertised as Mauve Wine whereas it probably would not if the color were called Paris Mud. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Imposex in Plicopurpura Pansa (Neogastropoda: Thaididae)

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 86 (2015) 531–534 www.ib.unam.mx/revista/ Research note Imposex in Plicopurpura pansa (Neogastropoda: Thaididae) in Nayarit and Sinaloa, Mexico Imposex en Plicopurpura pansa (Neogastropoda: Thaididae) en Nayarit and Sinaloa, México Delia Domínguez-Ojeda a, Olga Araceli Patrón-Soberano b, José Trinidad Nieto-Navarro a,∗, María de Lourdes Robledo-Marenco c, Jesús Bernardino Velázquez-Fernández c a Escuela Nacional de Ingeniería Pesquera, Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit, Bahía de Matanchén km 12, carretera a Los Cocos, 63740, San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico b División de Biología Molecular, Instituto Potosino de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Camino a la presa de San José, Núm. 2055, Lomas 4ta, Sección, 78216 San Luís Potosí, Mexico c Laboratorio de Contaminación y Toxicología Ambiental, Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit, Ciudad de la Cultura Amado Nervo, S/N, Los Fresnos, 63155, Tepic, Nayarit, Mexico Received 25 June 2014; accepted 10 February 2015 Available online 26 May 2015 Abstract Imposex is the development of male features in female prosobranch gastropods, caused by organotin compounds. In the Mexican Pacific coast, imposex was observed in Plicopurpura pansa. This snail has been used by indigenous people to dye cotton and traditional fabric clothing. During 2010 and 2011, 5 habitats were visited along the coastline of Nayarit and Sinaloa, Mexico. At low tide, 675 snails were collected. Shell length, sex ratio and imposex incidence were measured. Imposex incidences were higher in the samples collected near harbor areas. -

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure

The Use of Pleasure Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality Michel Foucault Translated from the French by Robert Hurley Vintage Books . A Division of Random House, Inc. New York The Use of Pleasure Books by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History oflnsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language) The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. ... A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes I, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 VINTAGE BOOKS EDlTlON, MARCH 1990 Translation copyright © 1985 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as L' Usage des piaisirs by Editions Gallimard. Copyright © 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in October 1985. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality. Translation of Histoire de la sexualite. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. I. An introduction-v. 2. The use of pleasure. I. Sex customs-History-Collected works. -

Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Galliker, Julia, "Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204)" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 27. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker, University of Michigan In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. 346-373. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013).