Campus Prophets, Spiritual Guides, Or Interfaith Traffic Directors?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: Never Forget: Ground Zero, Park51, and Constitutive Rhetorics

Title: Never Forget: Ground Zero, Park51, and Constitutive Rhetorics Author: Tamara Issak Issue: 3 Publication Date: November 2020 Stable URL: http://constell8cr.com/issue-3/never-forget-ground-zero-park51-and-constitutive-rh etorics/ constellations a cultural rhetorics publishing space Never Forget: Ground Zero, Park51, and Constitutive Rhetorics Tamara Issak, St. John’s University Introduction It was the summer of 2010 when the story of Park51 exploded in the news. Day after day, media coverage focused on the proposal to create a center for Muslim and interfaith worship and recreational activities in Lower Manhattan. The space envisioned for Park51 was a vacant department store which was damaged on September 11, 2001. Eventually, it was sold to Sharif El-Gamal, a Manhattan realtor and developer, in July of 2009. El-Gamal intended to use this space to build a community center open to the general public, which would feature a performing arts center, swimming pool, fitness center, basketball court, an auditorium, a childcare center, and many other amenities along with a Muslim prayer space/mosque. Despite the approval for construction by a Manhattan community board, the site became a battleground and the project was hotly debated. It has been over ten years since the uproar over Park51, and it is important to revisit the event as it has continued significance and impact today. The main argument against the construction of the community center and mosque was its proximity to Ground Zero. Opponents to Park51 argued that the construction of a mosque so close to Ground Zero was offensive and insensitive because the 9/11 attackers were associated with Islam (see fig. -

Living Tradition

Jesus Is Just Alright With Me April 13, 2014 Rev. John L. Saxon I This past year, Karla and I have been preaching a series of sermons on the six sources of what we call the “living tradition” of our Unitarian Universalist faith: direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder, affirmed in all cultures, that moves us to a renewal of the spirit and an openness to the forces that create and uphold life; words and deeds of prophetic women and men that challenge us to confront powers and structures of evil with justice, compassion, and the transforming power of love; wisdom from the world’s religions which inspires us in our ethical and spiritual life; humanist teachings that counsel us to heed the guidance of reason and the results of science, warning us against the idolatries of mind and spirit; and spiritual teachings of earth-centered traditions that celebrate the sacred circle of life and instruct us to live in harmony with the rhythms of nature. But wait! That’s just five!!! There’s one more! I wonder what it could be? Let me think. (Pause.) Oh, now I remember! It’s Jewish and Christian teachings that call us to respond to God’s love by loving our neighbors as ourselves. II Now let’s face it. Claiming Jewish and Christian—especially Christian—teachings as one of the sources of Unitarian Universalism makes some UUs more than a little bit uncomfortable. There’s more than a little bit of truth in the joke that the only time you hear a UU say “Jesus Christ” is when she spills hot coffee in her lap during coffee hour on Sunday. -

Music App in AZ

An exhibition for children and families to celebrate the diversity of Muslim cultures in America and around the world through art, architecture, design, music, travel, trade, and more! February 2016 – Present By the Children’s Museum of Manhattan New York Cultural Series Raonale Start Early “Research clearly shows that children not only recognize race from a very young age, but also develop racial biases by age three to five.” Winkler, E.N. “Children Are Not Colorblind: How Young Children Learn Race” HighReach Learning Inc., 2009 Offer Variety “When children are taught to pay aenon to mulple aributes of a person at once, reduced levels of bias are shown.” Aboud, F.E. (2008) in Winkler, E.N. “Children Are Not Colorblind: How Young Children Learn Race” HighReach Learning Inc., 2009. Provide Time to Pracce “Understanding a point of view other than your own takes knowledge, skills, perspec)ve and values. Developing these four also takes pracce – learning to apply and transfer these four from one topic to another.” UNESCO’s Educaon for Sustainable Development in Acon Teaching young children to have mulple perspecves “…is likely to reduce problems involving prejudice or discriminaon and is an important component of early childhood educaon.” United Naons Educaonal, Scienfic and Cultural Organizaon. “Exploring Sustainable Development: A Mulple-Perspecve Approach.” UNESCO: Educaon for Sustainable Development in Acon Learning & Training Tools Number 3. 2012 Exhibit Goals 1. Introduce families to the beauful and joyful diversity and commonalies in contemporary Muslim communies in New York City, the United States, and around the world. 2. Immerse children in interacve, fun and accessible ways so as to give families a new posive forum in which they can discuss Muslim cultures 3. -

Mindingbusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES

BULLETIN MindingBusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES WINTER 2018 In this ISSUE WINTER 2018 40 38 Minding the Business How Charlie Albert ’69, JJ Rademaekers ’89, AK Kennedy L’Heureux ’90, and James McKinnon ’87 achieved entrepreneurial success—and DEPARTMENTS became their own bosses 3 On Main Hall By Neil Vigdor ’95 8 Alumni Spotlight 16 Around the Pond 32 Sports 38 Larry Stone Tribute 66 Alumni Notes 58 106 Milestones How to Work Smarter, Not Harder The Moorhead Academic Center and Jon Willson ’82 in action By Julie Reiff 58 40 m Taft varsity football celebrates their 41–23 victory over Hotchkiss School on November 11. ROBERT FALCETTI Taft Bulletin / WINTER 2018 1 On Main Hall A WORD FROM HEADMASTER WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 WINTER 2018 Volume 88, Number 2 EDITOR Linda Hedman Beyus DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli THE RIGORS AND REWARDS OF ACCREDITATION ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Debra Meyers There are lots of ways schools improve. Boards plan strategically, heads and “We have hard ON THE COVER administrative teams examine and change practices, and faculty experiment PHOTOGRAPHY work to do, but it’s A model of a Chuggington® train—inspired by the Robert Falcetti and innovate. But for schools like Taft, there’s another critical way: the New children’s animated show of the same name—greets England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) Accreditation Process. It’s a the glorious work readers on this issue’s cover! Read the feature on ALUMNI NOTES EDITOR pages 40–57 about four alumni who create and make really rigorous methodology that ensures accredited schools regularly reflect, Hillary Dooley on challenges different products, including toy/games designer plan, and innovate; and it’s this process Taft just finished. -

Minister's Musings

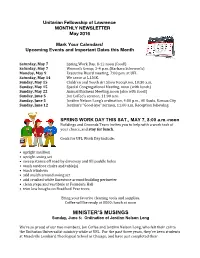

Unitarian Fellowship of Lawrence MONTHLY NEWSLETTER May 2016 Mark Your Calendars! Upcoming Events and Important Dates this Month Saturday, May 7 Spring Work Day, 8-12 noon (food!) Saturday, May 7 Women’s Group, 2-4 p.m. (Barbara Schowen’s) Monday, May 9 Executive Board meeting, 7:00 p.m. at UFL Saturday, May 14 We serve at L.I.N.K. Sunday, May 15 Children and Youth Art Show Reception, 10:30 a.m. Sunday, May 15 Special Congregational Meeting, noon (with lunch) Sunday, May 22 Annual Business Meeting, noon (also with food!) Sunday, June 5 Jon Coffee’s sermon, 11:00 a.m. Sunday, June 5 Jordinn Nelson Long’s ordination, 4:00 p.m., All Souls, Kansas City Sunday, June 12 Jordinn’s “Good-bye” sermon, 11:00 a.m. Reception following SPRING WORK DAY THIS SAT., MAY 7, 8:00 a.m.-noon Buildings and Grounds Team invites you to help with a work task of your choice, and stay for lunch. Goals for UFL Work Day include: • upright mailbox • upright swing set • sweep stones off road by driveway and fill puddle holes • wash outdoor chairs and table(s) • wash windows • add mulch around swing set • add crushed white limestone around building perimeter • clean steps and vestibule at Founders Hall • trim low boughs on Bradford Pear trees Bring your favorite cleaning tools and supplies. Coffee will be ready at 0800; lunch at noon MINISTER’S MUSINGS Sunday, June 5: Ordination of Jordinn Nelson Long We're so proud of our two members, Jon Coffee and Jordinn Nelson Long, who felt their call to the Unitarian Universalist ministry while at UFL. -

Works on Theology and Vocation

An Annotated Bibliography of Works Pertinent to Vocation and Values Works on Theology and Vocation: Title Author/Publisher Work Description A collection of theological essays from a multi- and interdisciplinary approach, stemming from Loyola University John Haughey, S. J., editor; 2003 Revisiting the Idea of Vocation: of Chicago’s participation in the The Catholic University of Theological Explorations Programs for the Theological America Press Exploration of Vocation. The volume includes essays written from Jewish and Islamic perspectives. Gilbert C. Meilander; 2000 Notre This collection offers a Working: Its Meaning and Its Dame Press comprehensive look at work by Limits different authors. Historical review of professional life in America and the impact of Work and Integrity: The Crisis William Sullivan; 1995 globalization, technology, and and Promise of Professionalism HarperCollins changing work patterns on in America professionals. The book promotes civic responsibilities for professionals, and commitments to the larger society. Guide to help people discover R. J. Ledier & D. A. Shapiro; Whistle While You Work and heed their callings, using 2001 Berrett-Koehler stories and exercises. Best-seller for twenty-five years— helps job hunters define their Richard N. Bolles; 2002 Ten What Color is Your Parachute? interests, experience, goals, and Speed Press state of mind, then points them in the direction of a suitable, satisfying and profitable career. Arguing that all work should have The Reinvention of Work: A dignity, Fox envisions a work Matthew Fox; 1995 Harper San New Vision of Livelihood for world in which intellect, heart, Francisco Our Time and health harmonize to celebrate the whole person. Drawing on interviews with fast- trackers, Albion shares how these Making a Life, Making a Living: Mark Albion; 2000 Warner Books men and women found the Reclaiming Your Purpose and courage and motivation to re- Passion in Business and Life create successful professional lives guided by passion. -

Citizenship Under Siege Humanities in the Public Square VOL

VOL. 20, NO. 1 | WINTER 2017 CIVIC LEARNING FOR SHARED FUTURES A Publication of the Association of American Colleges and Universities Citizenship Under Siege Humanities in the Public Square VOL. 20, NO. 1 | WINTER 2017 KATHRYN PELTIER CAMPBELL, Editor TABLE OF CONTENTS BEN DEDMAN, Associate Editor ANN KAMMERER, Design 3 | From the Editor MICHELE STINSON, Production Manager DAWN MICHELE WHITEHEAD, Editorial Advisor Citizenship Under Siege SUSAN ALBERTINE, Editorial Advisor 4 | Diversity and the Future of American Democracy TIA BROWN McNAIR, Editorial Advisor WILLIAM D. ADAMS, National Endowment for the Humanities CARYN McTIGHE MUSIL, Senior Editorial 7 | Clashes Over Citizenship: Lady Liberty, Under Construction or On the Run? Advisor CARYN McTIGHE MUSIL, Association of American Colleges and Universities ANNE JENKINS, Senior Director for Communications 10 | Bridges of Empathy: Crossing Cultural Divides through Personal Narrative and Performance Advisory Board DONA CADY and MATTHEW OLSON—both of Middlesex Community College; and DAVID HARVEY CHARLES, University at Albany, PRICE, Santa Fe College State University of New York 13 | Affirming Interdependency: Interfaith Encounters through the Humanities TIMOTHY K. EATMAN, Rutgers University / Imagining America DEBRA L. SCHULTZ, Kingsborough Community College, City University of New York KEVIN HOVLAND, NAFSA: Association 16 | Addressing Wicked Problems through Deliberative Dialogue of International Educators JOHN J. THEIS, Lone Star College System, and FAGAN FORHAN, Mount Wachusett ARIANE HOY, -

Leading Spiritual Diversity in Higher Education: Summer Professional Diploma Summer 2018

NYU STEINHARDT AND THE NYU OF MANY INSTITUTE FOR MULTIFAITH LEADERSHIP LEADING SPIRITUAL DIVERSITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION: SUMMER PROFESSIONAL DIPLOMA SUMMER 2018 ABOUT THE PROGRAM As attention to diversity and inclusion surges at campuses around the country, the need for administrators, chaplains, and faculty to provide leadership intensifies. To address this challenge, the Of Many Institute for Multifaith Leadership at NYU and the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development are launching a Professional Diploma on Leading Spiritual Diversity within Higher Education. This four-day program will illuminate today’s pressing questions: How can we best How can we best How can we embed provide spiritual navigate the religious and spiritual leadership to those who complexities of religious literacy within are not members of our diversity within the broader conversations religious or spiritual bureaucracy of higher about diversity and tradition? education? inclusion? LEARNING FEATURED OBJECTIVES FACULTY — — DR. CHELSEA CLINTON CO-FOUNDER, NYU OF MANY INSTITUTE FOR MULTIFAITH LEADERSHIP DR. JAMES FRASER PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AND EDUCATION, NYU REV. DR. CHARLES L. HOWARD UNIVERSITY CHAPLAIN, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA IMAM KHALID LATIF EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ISLAMIC CENTER AT NYU DR. LINDA G. MILLS CO-FOUNDER, NYU OF MANY INSTITUTE FOR MULTIFAITH LEADERSHIP RABBI YEHUDA SARNA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, BRONFMAN CENTER FOR JEWISH STUDENT LIFE AT NYU DR. JOHN SEXTON PRESIDENT EMERITUS, NYU YAEL SHY, ESQ. SENIOR DIRECTOR, NYU OFFICE OF GLOBAL SPIRITUAL LIFE DR. SIMRAN JEET SINGH HENRY R. LUCE FELLOW FOR RELIGION IN INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR RELIGION AND MEDIA DR. VARUN SONI DEAN OF RELIGIOUS LIFE, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA DR. -

American Muslims

American Muslims American Muslims live in cities, towns and rural areas across {}the United States. Who are American { ? Muslims? } U N I T Y T H R O U G H D I V E R S I T Y : T H E A M E R I C A N I D E N T I T Y A few years ago I was doing research in the main reading room of the Library of Congress in Washington, when I took a short break to stretch my neck. As I stared up at the ornately painted dome 160 feet above me, the muscles in my neck loosened—and my eyes widened in surprise at what they saw. Painted on the library’s central dome were 12 winged men and women representing the epochs and influences that contributed to the advancement of civilization. Seated among these luminaries of history was a bronze-toned figure, depicted with a scientific instrument in a pose of by Samier Mansur deep thought. Next to him a plaque heralded the influence he represented: Islam. Left, the dome of the The fact that the world’s largest library, just steps from Library of Congress reading the U.S. Capitol, pays homage to the intellectual achievements room in Washington, D.C., depicts important influences of Muslims—alongside those of other groups—affirms a central on civilization, including tenet of American identity: The United States is not only Islam. Preceding page, a Muslim teenager gets a nation born of diversity, but one that thrives ready to play soccer in because of diversity. -

For Some, Religion Is Part of the College Experience

26 January 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com For Some, Religion Is Part of the College Experience Some students find new ways to explore and express religious attitudes, ideas and beliefs at college FAITH LAPIDUS: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I'm Faith Lapidus. Today on our show, we play music from singer Lana Del Rey. We also answer a question from Burma about the way Americans elect a president. But, first we go to real college to hear how some students combine religion with their school life. College Religious Life FAITH LAPIDUS: Going to college is often a chance for young adults to explore ideas and beliefs different from those they grew up with. As they do, college students are finding new ways to express their beliefs. As we hear from 2 Christopher Cruise, American clergy say many young people are remaining true to their religious faith. (SOUND) CHRISTOPHER CRUISE: A traditional observance gives Indian students a chance to share their faith and culture with others. Many did that at this recent event, says Chandni Raja of the Hindu Student Organization at the University of Southern California. CHANDNI RAJA: "Meeting other groups on campus and trying to get that dialogue going, while also maintaining our own communities as a strong place where people can come together." Varun Soni works as dean of religious life at the University of Southern California. He says many students keep religion on their own terms. VARUN SONI: "They're more interested, I find, in making religion work for them as opposed to working for it. -

The 500 Most Influential Muslims = 2009 First Edition - 2009

THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS = 2009 first edition - 2009 THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS IN THE WORLD = 2009 first edition (1M) - 2009 Chief Editors Prof John Esposito and Prof Ibrahim Kalin Edited and Prepared by Ed Marques, Usra Ghazi Designed by Salam Almoghraby Consultants Dr Hamza Abed al Karim Hammad, Siti Sarah Muwahidah With thanks to Omar Edaibat, Usma Farman, Dalal Hisham Jebril, Hamza Jilani, Szonja Ludvig, Adel Rayan, Mohammad Husni Naghawi and Mosaic Network, UK. all photos copyright of reuters except where stated All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the prior consent of the publisher. © the royal islamic strategic studies centre, 2009 أ �� ة � � ن ة � �ش� ة الم�م��لك�� ا �ل� ر د ��ة�� ا ل�ها �مة�� ة � � � أ ة � ة ة � � ن ة �� ا �ل� ���د ا �ل�د �ى د ا � � ال�مك� �� ا �ل� ل�ط� �� ر م أ ة ع ر ن و ة (2009/9/4068) ة � � ن � � � ة �ة ن ن ة � ن ن � � ّ ن � ن ن ة�����ح�م� ال�م�أ ��ل� كل� �م� ال�م��س�أ � ���� ا ��لها �ل� ���� �ع ن �محة� � �م�ط��ه�� � �ل� ���ه�� �ه�� ا ال�م�ط��� �ل و أ �ل و وة وة � أ أوى و ة نأر ن � أ ة ���ة ة � � ن ة � ة � ة ن � . �ع� ر ا �ةى د ا �ر � الم ك��ن �� ا �ل�و ل�ط�ة�� ا �و ا �ةى ن��ه�� �ح �ل�و�مة�� ا �ر�ى ISBN 978-9957-428-37-2 املركز امللكي للبحوث والدراسات اﻹسﻻمية )مبدأ( the royal islamic strategic studies centre The Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding Edmund A. -

Being Muslim in America

UNITED STATE S DEPARTMENT OF STATE / BU REA U OF INTERNATIONAL INFORMATION PROGRAM S Being Muslim inAmerica INTROD U CTION “I AM A N AMER I C A N WI TH A MUSL I M SOUL ” ........... 2 PHOTO Ess AY he young women pictured on our cover BUILDING A LI FE IN AMER I C A ........... 4 are both Muslim. They live near Detroit, TMichigan, in a community with many Arab- ROFILE S American residents. Each expresses her faith in P her own way, with a combination of traditional YOUNG MUSL I MS MA KE THE I R MA RK ........... 30 and modern dress. Here, they compete fiercely on the basketball court in a sport that blends RE S O U RCE S individual skills and team effort. They — along A STAT I ST I C A L PORTR ai T ........... 48 with the other men, women, and children in this E I GH B ORHOOD OSQUES publication — demonstrate every day what it is N M ........... 52 like to be Muslim in America. TIMELINE OF KE Y EVENTS ........... 56 BibLIOGRapHY ........... 63 SU PPLEMENT DID YOU KNO W ?/PERFORMERS MI N I -P OSTER 1 of Hindu temples. In fact, there are now more Ages, my soul spread to the East and West, Muslims in America than Episcopalians, the praying in the mosques and studying in the faith professed by many of America’s Found- libraries of the great medieval Muslim cities ing Fathers. of Cairo, Baghdad, and Cordoba. My soul whirled with Rumi, read Aristotle with Aver- One hundred years ago, the great African- roes, traveled through Central Asia with Nasir American scholar W.E.B.