Living Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campus Prophets, Spiritual Guides, Or Interfaith Traffic Directors?

Campus Prophets, Spiritual Guides, or Interfaith Traffic Directors? The Many Lives of College and University Chaplains The Luce Lectures on the Changing Role of Chaplains in American Higher Education Based on a Lecture Delivered on November 13, 2018 John Schmalzbauer Department of Religious Studies Missouri State University 901 South National Avenue Springfield, MO 65897 Email: [email protected] What roles do chaplains play in contemporary American higher education? Drawing on the National Study of Campus Ministries (2002-2008), this paper contrasts the post-war chaplaincy with its twenty-first century successor. While a relatively young occupation, the job of the college chaplain has shifted greatly over the past sixty years. Vastly different from the 1950s, the demographic profile of college chaplains has also changed, reflecting the growing presence of women clergy and the diversification of the American campus. Accompanying these shifts, changes in American religion have transformed the context of the profession. Though some things have remained the same (chaplains still preach, counsel, and preside over religious services), other things are very different. On the twenty-first century campus, chaplains have increasingly found themselves occupying the roles of campus prophets, spiritual guides, and interfaith traffic directors, a combination that did not exist in the mid-century chaplaincy.1 In chronicling these changes, it is helpful to compare accounts of post-war chaplaincy with the twenty-first century profession. Historian Warren Goldstein’s work on Yale University chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Jr. looms large in this comparison. For a whole generation of mainline Protestants, Coffin modeled an approach to chaplaincy that emphasized the public, prophetic components of the role, accompanying the Freedom Riders and protesting the Vietnam War. -

Mindingbusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES

BULLETIN MindingBusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES WINTER 2018 In this ISSUE WINTER 2018 40 38 Minding the Business How Charlie Albert ’69, JJ Rademaekers ’89, AK Kennedy L’Heureux ’90, and James McKinnon ’87 achieved entrepreneurial success—and DEPARTMENTS became their own bosses 3 On Main Hall By Neil Vigdor ’95 8 Alumni Spotlight 16 Around the Pond 32 Sports 38 Larry Stone Tribute 66 Alumni Notes 58 106 Milestones How to Work Smarter, Not Harder The Moorhead Academic Center and Jon Willson ’82 in action By Julie Reiff 58 40 m Taft varsity football celebrates their 41–23 victory over Hotchkiss School on November 11. ROBERT FALCETTI Taft Bulletin / WINTER 2018 1 On Main Hall A WORD FROM HEADMASTER WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 WINTER 2018 Volume 88, Number 2 EDITOR Linda Hedman Beyus DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli THE RIGORS AND REWARDS OF ACCREDITATION ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Debra Meyers There are lots of ways schools improve. Boards plan strategically, heads and “We have hard ON THE COVER administrative teams examine and change practices, and faculty experiment PHOTOGRAPHY work to do, but it’s A model of a Chuggington® train—inspired by the Robert Falcetti and innovate. But for schools like Taft, there’s another critical way: the New children’s animated show of the same name—greets England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) Accreditation Process. It’s a the glorious work readers on this issue’s cover! Read the feature on ALUMNI NOTES EDITOR pages 40–57 about four alumni who create and make really rigorous methodology that ensures accredited schools regularly reflect, Hillary Dooley on challenges different products, including toy/games designer plan, and innovate; and it’s this process Taft just finished. -

The Byrds the Very Best of the Byrds Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Byrds The Very Best Of The Byrds mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Very Best Of The Byrds Country: Canada Released: 2008 Style: Folk Rock, Psychedelic Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1369 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1614 mb WMA version RAR size: 1322 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 227 Other Formats: ADX MP4 MPC DMF XM AIFF AU Tracklist 1 Mr. Tambourine Man 2:33 2 I'll Feel A Whole Lot Better 2:35 3 All I Really Want To Do 2:06 4 Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is A Season) 3:53 5 The World Turns All Around Her 2:16 6 It's All Over Now, Baby Blue 4:55 7 5D (Fifth Dimension) 2:36 8 Eight Miles High 3:38 9 I See You 2:41 10 So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star 2:09 11 Have You Seen Her Face 2:43 12 You Ain't Goin' Nowhere 2:37 13 Hickory Wind 3:34 14 Goin' Back 3:58 15 Change Is Now 3:25 16 Chestnut Mare 5:09 17 Chimes Of Freedom 3:54 18 The Times They Are A-Changin' 2:21 19 Dolphin's Smile 2:01 20 My Back Pages 3:11 21 Mr. Spaceman 2:12 22 Jesus Is Just Alright 2:12 23 This Wheel's On Fire 4:47 24 Ballad Of Easy Rider 2:04 Credits Artwork By – David Axtell Compiled By – Sharon Hardwick, Tim Fraser-Harding Photography By – Don Hunstein, Sandy Speiser Notes Packaged in Discbox Slider. -

Minister's Musings

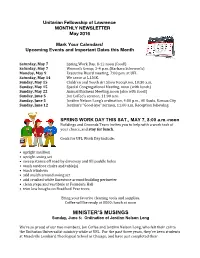

Unitarian Fellowship of Lawrence MONTHLY NEWSLETTER May 2016 Mark Your Calendars! Upcoming Events and Important Dates this Month Saturday, May 7 Spring Work Day, 8-12 noon (food!) Saturday, May 7 Women’s Group, 2-4 p.m. (Barbara Schowen’s) Monday, May 9 Executive Board meeting, 7:00 p.m. at UFL Saturday, May 14 We serve at L.I.N.K. Sunday, May 15 Children and Youth Art Show Reception, 10:30 a.m. Sunday, May 15 Special Congregational Meeting, noon (with lunch) Sunday, May 22 Annual Business Meeting, noon (also with food!) Sunday, June 5 Jon Coffee’s sermon, 11:00 a.m. Sunday, June 5 Jordinn Nelson Long’s ordination, 4:00 p.m., All Souls, Kansas City Sunday, June 12 Jordinn’s “Good-bye” sermon, 11:00 a.m. Reception following SPRING WORK DAY THIS SAT., MAY 7, 8:00 a.m.-noon Buildings and Grounds Team invites you to help with a work task of your choice, and stay for lunch. Goals for UFL Work Day include: • upright mailbox • upright swing set • sweep stones off road by driveway and fill puddle holes • wash outdoor chairs and table(s) • wash windows • add mulch around swing set • add crushed white limestone around building perimeter • clean steps and vestibule at Founders Hall • trim low boughs on Bradford Pear trees Bring your favorite cleaning tools and supplies. Coffee will be ready at 0800; lunch at noon MINISTER’S MUSINGS Sunday, June 5: Ordination of Jordinn Nelson Long We're so proud of our two members, Jon Coffee and Jordinn Nelson Long, who felt their call to the Unitarian Universalist ministry while at UFL. -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

WDAM Radio's History of the Byrds

WDAM Radio's Hit Singles History Of The Byrds # Artist Title Chart Comments Position/Year 01 Jet Set “The Only One I Adore” –/1964 Jim McGuinn, Gene Clark & David Crosby with studio musicians 02 Beefeaters “Please Let Me Love You” –/1964 03 Byrds “Mr. Tambourine Man” #1/1965 Jim McGuinn, Gene Clark, David Crosby, Michael Clarke & Chris Hillman. Only Jim McGuinn played on this recording with the Wrecking Crew studio musicians. 03A Bob Dylan “Mr. Tambourine Man” #6-Albums/ From Bringing It All Back Home. 1965 03B Brothers Four “Mr. Tambourine Man” #118-Albums/ Recorded in1964, but not issued until 1965.The 1965 Brothers Four had some management connection with Bob Dylan and had even shared some gigs. In late 1963, following JFK's assassination, the Brothers Four began looking at more serious material and were presented with some Bob Dylan demos. Among his songs the group chose to record was Mr. Tambourine Man. Bob Dylan has say over who first releases one of his songs and, since he didn't care for the Brothers Four's arrangement, it wasn't immediately issued. It appeared on their The Honey Wind Blows album following the Byrds' hit and Bob Dylan's own version. 04 Byrds “All I Really Want To Do” #40/1965 A-side of I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better. 04A Cher “All I Really Want To Do” #15/1965 Cher’s first solo hit single. 04B Bob Dylan “All I Really Want To Do” #43-Albums/ From Another Side Of Bob Dylan. 1964 05 Byrds “I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better” #103/1965 B-side of All I Really Want To Do. -

Works on Theology and Vocation

An Annotated Bibliography of Works Pertinent to Vocation and Values Works on Theology and Vocation: Title Author/Publisher Work Description A collection of theological essays from a multi- and interdisciplinary approach, stemming from Loyola University John Haughey, S. J., editor; 2003 Revisiting the Idea of Vocation: of Chicago’s participation in the The Catholic University of Theological Explorations Programs for the Theological America Press Exploration of Vocation. The volume includes essays written from Jewish and Islamic perspectives. Gilbert C. Meilander; 2000 Notre This collection offers a Working: Its Meaning and Its Dame Press comprehensive look at work by Limits different authors. Historical review of professional life in America and the impact of Work and Integrity: The Crisis William Sullivan; 1995 globalization, technology, and and Promise of Professionalism HarperCollins changing work patterns on in America professionals. The book promotes civic responsibilities for professionals, and commitments to the larger society. Guide to help people discover R. J. Ledier & D. A. Shapiro; Whistle While You Work and heed their callings, using 2001 Berrett-Koehler stories and exercises. Best-seller for twenty-five years— helps job hunters define their Richard N. Bolles; 2002 Ten What Color is Your Parachute? interests, experience, goals, and Speed Press state of mind, then points them in the direction of a suitable, satisfying and profitable career. Arguing that all work should have The Reinvention of Work: A dignity, Fox envisions a work Matthew Fox; 1995 Harper San New Vision of Livelihood for world in which intellect, heart, Francisco Our Time and health harmonize to celebrate the whole person. Drawing on interviews with fast- trackers, Albion shares how these Making a Life, Making a Living: Mark Albion; 2000 Warner Books men and women found the Reclaiming Your Purpose and courage and motivation to re- Passion in Business and Life create successful professional lives guided by passion. -

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe on the Run Time the Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe On the Run Time The Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse Pink Floyd – The Wall In the Flesh The Thin Ice Another Brick in the Wall (Part 1) The Happiest Days of our Lives Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2) Mother Goodbye Blue Sky Empty Spaces Young Lust Another Brick in the Wall (Part 3) Hey You Comfortably Numb Stop The Trial Run Like Hell Laser Queen Bicycle Race Don't Stop Me Now Another One Bites The Dust I Want To Break Free Under Pressure Killer Queen Bohemian Rhapsody Radio Gaga Princes Of The Universe The Show Must Go On 1 Laser Rush 2112 I. Overture II. The Temples of Syrinx III. Discovery IV. Presentation V. Oracle: The Dream VI. Soliloquy VII. Grand Finale A Passage to Bangkok The Twilight Zone Lessons Tears Something for Nothing Laser Radiohead Airbag The Bends You – DG High and Dry Packt like Sardine in a Crushd Tin Box Pyramid song Karma Police The National Anthem Paranoid Android Idioteque Laser Genesis Turn It On Again Invisible Touch Sledgehammer Tonight, Tonight, Tonight Land Of Confusion Mama Sussudio Follow You, Follow Me In The Air Tonight Abacab 2 Laser Zeppelin Song Remains the Same Over the Hills, and Far Away Good Times, Bad Times Immigrant Song No Quarter Black Dog Livin’, Lovin’ Maid Kashmir Stairway to Heaven Whole Lotta Love Rock - n - Roll Laser Green Day Welcome to Paradise She Longview Good Riddance Brainstew Jaded Minority Holiday BLVD of Broken Dreams American Idiot Laser U2 Where the Streets Have No Name I Will Follow Beautiful Day Sunday, Bloody Sunday October The Fly Mysterious Ways Pride (In the Name of Love) Zoo Station With or Without You Desire New Year’s Day 3 Laser Metallica For Whom the Bell Tolls Ain’t My Bitch One Fuel Nothing Else Matters Master of Puppets Unforgiven II Sad But True Enter Sandman Laser Beatles Magical Mystery Tour I Wanna Hold Your Hand Twist and Shout A Hard Day’s Night Nowhere Man Help! Yesterday Octopus’ Garden Revolution Sgt. -

For Some, Religion Is Part of the College Experience

26 January 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com For Some, Religion Is Part of the College Experience Some students find new ways to explore and express religious attitudes, ideas and beliefs at college FAITH LAPIDUS: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I'm Faith Lapidus. Today on our show, we play music from singer Lana Del Rey. We also answer a question from Burma about the way Americans elect a president. But, first we go to real college to hear how some students combine religion with their school life. College Religious Life FAITH LAPIDUS: Going to college is often a chance for young adults to explore ideas and beliefs different from those they grew up with. As they do, college students are finding new ways to express their beliefs. As we hear from 2 Christopher Cruise, American clergy say many young people are remaining true to their religious faith. (SOUND) CHRISTOPHER CRUISE: A traditional observance gives Indian students a chance to share their faith and culture with others. Many did that at this recent event, says Chandni Raja of the Hindu Student Organization at the University of Southern California. CHANDNI RAJA: "Meeting other groups on campus and trying to get that dialogue going, while also maintaining our own communities as a strong place where people can come together." Varun Soni works as dean of religious life at the University of Southern California. He says many students keep religion on their own terms. VARUN SONI: "They're more interested, I find, in making religion work for them as opposed to working for it. -

Copyrighted Material

c01.qxd 2/20/07 9:37 AM Page 3 1 THE POPULAR CULTURE WE ARE IN Whoever marries the spirit of this age will find himself a widower in the next. WILLIAM R. INGE In 1966, sitting in San Francisco’s Fillmore West between two guys who were smoking marijuana on the overstuffed couch, listening to Jefferson Airplane, way before the trendy bracelet told me to, I asked myself, “What would Jesus do?” I was drawn to this question by what I observed around me. It was an age of spiritual yearning and an influential popular culture. It was an age of inauthentic churches and disillusioned youth. I could not have known then what I know now—that San Francisco, famous for its earthquakes, was in fact the epicenter of a cultural quake whose aftershocks are still felt to this day. The culturally seismic sixties gave rise to a powerful, pervasive popular culture offering both what Joni Mitchell described as “a song and a celebration”1 and a hopeful new path to spiritual enlightenment while dialogue about the divine morphed beyond the religious arena and into movies and music suddenly brimming with sacred lyrics. The COPYRIGHTEDDoobie Brothers belted out “Jesus MATERIAL Is Just Alright”; Norman Greenbaum declared, “You gotta have a friend in Jesus, so you know that when you die, he’s gonna recommend you to the spirit in the sky.”2 The Beatles embodied the leap to the East, a widespread interest in Hinduism and Japanese Buddhism. George Harrison, the only Beatle for whom Eastern religion actually stuck, sang his trib- ute to Krishna, “My Sweet Lord.” Joni Mitchell’s “Ladies of the 3 c01.qxd 2/20/07 9:37 AM Page 4 4 THE CULTURALLY SAVVY CHRISTIAN Canyon” weighed in with all the fury and insight of an Old Testa- ment prophet, denouncing consumerism, fame, and apathy about the environment. -

2015 Ministry Days WELCOME!

Unitarian Universalist Minsters Association 2015 Ministry Days June 22-24, 2015 — Oregon Convention Center (Portland, OR) WELCOME! We bid you welcome! Welcome to those who come with a twinkle in your eye and spring in your step, joyful to be a new minister. Welcome to those who are here for the very first time; and to those who stopped counting years ago. Welcome to those who come with a tired spirit and a heart broken from a year of disappointment. Welcome to those who come looking forward to a new chapter and ministry in life and those who are mourning that which just ended. Welcome to those extroverts who come eager for the energy only 650 colleagues can provide. Welcome to those introverts who come yearning for peace and solitude in the midst of the chaos. Welcome to those who come for words of inspiration and hope; and to those who come to sing and be held by music Welcome to those who we can touch and hug in Portland; to those in front of computer screens around the globe. Welcome… one and all. — Rev. Don Southworth All main events will be held in Ministry Days 2015 Schedule Portland Ballroom 254-255 Monday, June 22: DoubleTree Hotel ________________ Are you on Facebook? Chapter Leader Retreat (Adams/Jefferson) 8:00 AM - 5:00 PM Twitter? Instagram? Google+? Registration (Portland DoubleTree EMC: ) 2:00 PM - 7:30 PM Use #ministrydays when you Choir Rehearsal 4:30 PM - 5:30 PM post so our colleagues at home Reception/Welcome (Portland DoubleTree EMC) 7:30 PM - 10:00 PM can follow along! Follow the UUMA at: Tuesday, June 23: Oregon Convention Center _________ facebook.com/uuministers Registration Continues (Portland Ballroom Lobby) 7:30 AM - 5:00 PM and @UUMinAssoc on Spiritual Practices (See page 8) 7:30 AM - 8:15 AM Twitter Quiet Space (E147) 7:30 AM - 2:30 PM Have you signed up for Opening Worship — Including Child Dedication 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM Ministry Days text updates Snack Break 10:00 AM - 10:15 AM yet? Text @UUMinistersMD to 23559 to sign up! Staying Keynote: Rev. -

Harry's Music

Harry’s Music Although Harry’s song list spans more than 4 decades, this sample list of songs represents where Harry came from musically. Most of these songs have played a big role in his development and mindset over many years. All of them bring back great memories of friends and places. More recently he has added some great country songs into his shows, such as songs by Keith Urban, Chris Stapleton, and Thomas Rhett. He cut an album of originals over ten years ago, called “Traynham, Goddard, Cornett,” with Alan Cornett and longtime friend and bass man, Brian Goddard. Many of the cuts were written by Traynham and Goddard. The project was recorded in Boston and the stress of travel and deadlines was too much to handle. At this point, no followup recordings have been planned, but you can listen to the album in the audio section of the website (coming soon). The stage is where the magic is for Harry and that's the way it's always been. Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers America Paul Simon Alabama Neil Young All My Lovin’ Beatles Amy Pure Prairie League Any Major Dude Steely Dan Asphalt Dreams Michael Tomlinson As Tears Go By Rolling Stones As The Raven Flies Dan Fogelberg Autumn Edgar Winter Baba O’Reilly Who Baby Please Dave Mason Bad Company Doors Badge Eric Clapton Bad Moon Rising Creedence C R Before The Deluge Jackson Browne Behind Blue Eyes Who Believe In You Jude Cole Benny And The Jets Elton John Biko Peter Gabriel Blackbird Beatles Black Water Doobie Brothers Bluebird Beatles Blue Skies Allman Brothers Boat Drinks Jimmy Buffet Bodhisatva Steely Dan Boys of Summer Don Henley Breakdown Tom Petty Break On Through Doors Brighter Days Loggins & Messina Brillant Disguise Bruce Springsteen Broken Wings Mr.