What Can Language Biographies Reveal About Multilingualism in the Habsburg Monarchy? a Case Study on the Members of the Illyrian Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hungarian Historical Review “Continuities and Discontinuities

The Hungarian Historical Review New Series of Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 5 No. 1 2016 “Continuities and Discontinuities: Political Thought in the Habsburg Empire in the Long Nineteenth Century” Ferenc Hörcher and Kálmán Pócza Special Editors of the Thematic Issue Contents Articles MARTYN RADY Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) 5 FERENC HÖRCHER Enlightened Reform or National Reform? The Continuity Debate about the Hu ngarian Reform Era and the Example of the Two Széchenyis (1790–1848) 22 ÁRON KOVÁCS Continuity and Discontinuity in Transylvanian Romanian Thought: An Analysis of Four Bishopric Pleas from the Period between 1791 and 1842 46 VLASTA ŠVOGER Political Rights and Freedoms in the Croatian National Revival and the Croatian Political Movement of 1848–1849: Reestablishing Continuity 73 SARA LAGI Georg Jellinek, a Liberal Political Thinker against Despotic Rule (1885–1898) 105 ANDRÁS CIEGER National Identity and Constitutional Patriotism in the Context of Modern Hungarian History: An Overview 123 http://www.hunghist.org HHHR_2016_1.indbHR_2016_1.indb 1 22016.06.03.016.06.03. 112:39:582:39:58 Contents Book Reviews Das Preßburger Protocollum Testamentorum 1410 (1427)–1529, Vol. 1. 1410–1487. Edited by Judit Majorossy and Katalin Szende. Das Preßburger Protocollum Testamentorum 1410 (1427)–1529, Vol. 2. 1487–1529. Edited by Judit Majorossy und Katalin Szende. Reviewed by Elisabeth Gruber 151 Sopron. Edited by Ferenc Jankó, József Kücsán, and Katalin Szende with contributions by Dávid Ferenc, Károly Goda, and Melinda Kiss. Sátoraljaújhely. Edited by István Tringli. Szeged. Edited by László Blazovich et al. Reviewed by Anngret Simms 154 Egy székely két élete: Kövendi Székely Jakab pályafutása [Two lives of a Székely: The career of Jakab Székely of Kövend]. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 5–21 Martyn Rady Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) The Hungarian “constitution” was never balanced, for its sovereigns possessed a supervisory jurisdiction that permitted them to legislate by decree, mainly by using patents and rescripts. Although the right to proceed by decree was seldom abused by Hungary’s Habsburg rulers, it permitted the monarch on occasion to impose reforms in defiance of the Diet. Attempts undertaken in the early 1790s to hem in the ruler’s power by making the written law both fixed and comprehensive were unsuccessful. After 1867, the right to legislate by decree was assumed by Hungary’s government, and ministerial decree or “rendelet” was used as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Not only could rendelets be used to fill in gaps in parliamentary legislation, they could also be used to bypass parliament and even to countermand parliamentary acts, sometimes at the expense of individual rights. The tendency remains in Hungary for its governments to use discretionary administrative instruments as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Keywords: constitution, decree, patent, rendelet, legislation, Diet, Parliament In 1792, the Transylvanian Diet opened in the assembly rooms of Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) with a trio, sung by the three graces, each of whom embodied one of the three powers identified by Montesquieu as contributing to a balanced constitution.1 The Hungarian constitution, however, was never balanced. The power attached to the executive was always the greatest. Attempts to hem in the executive, however, proved unsuccessful. During the later nineteenth century, the legislature surrendered to ministers a large share of its legislative capacity, with the consequence that ministerial decree or rendelet often took the place of statute law. -

Ovdje Riječ, Ipak Je to Po Svoj Prilici Bio Hrvač, Što Bi Se Moglo Zaključiti Na Temelju Snažnih Ramenih I Leđnih Mišića

HRVATSKA UMJETNOST Povijest i spomenici Izdavač Institut za povijest umjetnosti, Zagreb Za izdavača Milan Pelc Recenzenti Sanja Cvetnić Marina Vicelja Glavni urednik Milan Pelc Uredništvo Vladimir P. Goss Tonko Maroević Milan Pelc Petar Prelog Lektura Mirko Peti Likovno i grafičko oblikovanje Franjo Kiš, ArTresor naklada, Zagreb Tisak ISBN: 978-953-6106-79-0 CIP HRVATSKA UMJETNOST Povijest i spomenici Zagreb 2010. Predgovor va je knjiga nastala iz želje i potrebe da se na obuhvatan, pregledan i koliko je moguće iscrpan način prikaže bogatstvo i raznolikost hrvatske umjetničke baštine u prošlosti i suvremenosti. Zamišljena je Okao vodič kroz povijest hrvatske likovne umjetnosti, arhitekture, gradogradnje, vizualne kulture i di- zajna od antičkih vremena do suvremenoga doba s osvrtom na glavne odrednice umjetničkog stvaralaštva te na istaknute autore i spomenike koji su nastajali tijekom razdoblja od dva i pol tisućljeća u zemlji čiji se politički krajobraz tijekom povijesnih razdoblja znatno mijenjao. Premda su u tako zamišljenom povijesnom ciceroneu svoje mjesto našli i najvažniji umjetnici koji su djelovali izvan domovine, žarište je ovog pregleda na umjetničkoj baštini Hrvatske u njezinim suvremenim granicama. Katkad se pokazalo nužnim da se te granice preskoče, odnosno da se u pregled – uvažavajući zadanosti povijesnih određenja – uključe i neki spomenici koji su danas u susjednim državama. Ovaj podjednako sintezan i opsežan pregled djelo je skupine uvaženih stručnjaka – specijalista za pojedina razdoblja i problemska područja hrvatske -

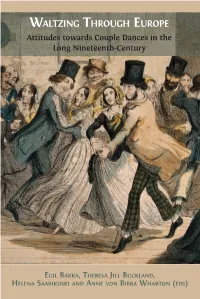

9. Dancing and Politics in Croatia: the Salonsko Kolo As a Patriotic Response to the Waltz1 Ivana Katarinčić and Iva Niemčić

WALTZING THROUGH EUROPE B ALTZING HROUGH UROPE Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the AKKA W T E Long Nineteenth-Century Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the Long Nineteenth-Century EDITED BY EGIL BAKKA, THERESA JILL BUCKLAND, al. et HELENA SAARIKOSKI AND ANNE VON BIBRA WHARTON From ‘folk devils’ to ballroom dancers, this volume explores the changing recep� on of fashionable couple dances in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards. A refreshing interven� on in dance studies, this book brings together elements of historiography, cultural memory, folklore, and dance across compara� vely narrow but W markedly heterogeneous locali� es. Rooted in inves� ga� ons of o� en newly discovered primary sources, the essays aff ord many opportuni� es to compare sociocultural and ALTZING poli� cal reac� ons to the arrival and prac� ce of popular rota� ng couple dances, such as the Waltz and the Polka. Leading contributors provide a transna� onal and aff ec� ve lens onto strikingly diverse topics, ranging from the evolu� on of roman� c couple dances in Croa� a, and Strauss’s visits to Hamburg and Altona in the 1830s, to dance as a tool of T cultural preserva� on and expression in twen� eth-century Finland. HROUGH Waltzing Through Europe creates openings for fresh collabora� ons in dance historiography and cultural history across fi elds and genres. It is essen� al reading for researchers of dance in central and northern Europe, while also appealing to the general reader who wants to learn more about the vibrant histories of these familiar dance forms. E As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the UROPE publisher’s website. -

DNEVNIK DRAGUTINA RAKOVCA Priopćili E

DNEVNIK DRAGUTINA RAKOVCA Priopćili E. LASZOWSKI i Dr. V. DEŽELIĆ ST. 25. Danas čitam u br. 84. novinah Narodnih, da je nj. jasnost herceg Filip Battyan 7) na prošnju župnika Ludbrežkoga, vicearkižakana V r a- ča n a 8) kao mestnoga škole ravnitelja, za školu, utemeljenu u svojoj gos- poštini Ludbregu, u ime knjigah i darovah za bolje napredujuću mladež, za e 4 5 školske godine 184 /4, 184 /5 i 184 /G odredio 10 for. srebra; i da se to od verhovnoga ovdašnje ga školskoga ravniteljstva dostavlja do obćenitoga znanja sa željom, da bi se, kamo sreće, i drugi, kojim je stalo do odhranjenja puka, ugledali u primer ovaj plemeniti - Kukavno po odhranjenje puka našega, ako bude zaviselo od velikašah (a stranom i plemićah) horvatskih, - U istom broju narodnih naših novinah čitam danas kratku pripovest, o novom zvonu, stolne cerkve zagrebačke; kao što sledi: »Prie dve godine u oči sv. Ladislava kralja dogodi se, da je glavno zvono stolne ceikve zagre- bačke puklo, tako da je bilo od potrebe dati ga prelevati. Preuzvišeni g. biskup zagrebački Ju raj Ha u I i k odredio je za istu sverhu 1000 for. Il srebru, u sled šta se je zvono odmah ovdašnjem zvonolevcu H e n r i k u De gen u Dl predalo, da ga prelije. Ovaj je delo sretno sveršio a d. 12. t. m. na dan sv. Maksimiliana bilo je isto zvono iz zvonolevarnice od osam, cvetjem i verpcami urešenih volovah na kolih izključivo za ovu sverhu na- pravljenih, praijeno od mnogobrojnoga puka uz svečanu tutnjavu sviuh zvo- novah k stolnoj d~rkvi doveženo i d. -

Bartulin's Tilting at Windmills

BARTULIN’S TILTING AT WINDMILLS: MANIPULATION AS A HISTORIOGRAPHIC METHOD (A reply to Nevenko Bartulin’s “Intelectual Discourse on Race and Culture in Croatia 1900-1945”) Tomislav JONJIĆ∗ In this article, which is written in a polemical tone, the author is making an eff ort to problematize a point of view from which the ideology of Croatian nationalism, the Ustasha movement and the Independent State of Croatia are even today being obsereved by a part of historiography. According to the au- thor, the ideology of Croatian nationalism has not suff ered much vital modi- fi cation since the mid-19th century until the end od the Second World War, rather it has kept itself occupied with justifying the right of Croats as a multi- confessional European nation to establish an independent state. Not just po- litical manifestations, but also literary and cultural achievements of the na- tionalist ideology protagonists clearly speak in that direction. Th e geopolitical position of Croatian lands, as well as the infl uence of foreign powers have not made the achievement of such a right of Croatian people and the evolution of Croatian nationalist ideology possible. As a result, that same nationalist ideol- ogy sometimes takes on foreign ideological and political infl uences which are visible only on its surface and purely out of tactial reasons. Th e Ustasha move- ment, being one of the manifestations of Croatian nationalism, is also charac- terized by ideological eclecticism. Th us, diff erent and sometimes contrastive statements made by the leading persona of Ustasha movement regarding their attitude towards the ideologies dominating Europe in the time aft er the First World War are therefore understandable. -

The Continuity Between the Enlightenment and Nationalism Politics and Historical Narratives of Narratives Andhistorical Politics

THE CONTINUITY BETWEEN THE ENLIGHTENMENT AND NATIONALISM: POLITICS AND HISTORICAL NARRATIVES OF THE CROATIAN NATIONAL REVIVAL By Vilim Pavlovic Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor László Kontler Second Reader: Professor Balázs Trencsényi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This thesis provides a look the fundamental programmatic articles of the Croatian National Revival. It attempts to first contextualize the Croatian national movement within the context of the Habsburg Monarchy, and especially in regards to the relationship of Croatia and Hungary. Secondly, the thesis attempts to explore the possible continuity between the ideology of the Croatian National Revival and the Enlightenment. This is done using some of the fundamental documents of the national movement. Looking at the political program of the national movement, I attempt to identify the influences of the Enlightenment in both explicit and implicit level. Furthermore, as this thesis is on a fundamental level concerned with nationalism, I will explore the interaction between the political programs of the national movement and historical narratives as both are often found in the same text. -

Misionári Ilyrizmu Etnicky Motivované Cestovanie Južných Slovanov V Tridsiatych a Štyridsiatych Rokoch 19

Východočeský sborník historický 23 2013 MISIONÁRI ILYRIZMU ETNICKY MOTIVOVANÉ CESTOVANIE JUŽNÝCH SLOVANOV V TRIDSIATYCH A ŠTYRIDSIATYCH ROKOCH 19. STOROČIA1) Marcela BEDNÁROVÁ Stúpenci južnoslovanského integračného hnutia, ilyrizmu, vychádzali z dobovej predstavy o jednote slovanského národa, ktorá bola personifi- kovaná v bytosti, nazývanej Matka Sláva (resp. Slávia). V užšom variante, v zmysle tzv. ilýrskeho národa, hovorili o Matke Domovine (Majka Domo- vina). Rozlišovali tak dva základné princípy, oživujúce, resp. oduševňujúce národ, členmi ktorého sa cítili byť. Matka Sláva zastupovala duchovný princíp všetkých Slovanov, pričom pojem Sláva (Slávia) mal dva významy: 1. označoval sa ním génius (duch) „slovanského národa“ a 2. vyjadroval územie, na ktorom žijú Slovania. Matka Domovina vystupovala v rámci užšieho pôsobenia – najčastejšie ako matka želanej „ilýrskej vlasti“. Národ bol v ponímaní ilýrcov spoločenstvom ľudí, ktorí sú „jedným sta- rodávnym pôvodom a jedným jazykom medzi sebou spríbuznení“.2) Okrem pôvodu a jazykovej príbuznosti ho prirovnávali k rodinným a pokrvným zväzkom tvrdiac, že národ je „jedna veľká rodina, ktorá je zložená z mno- hých menších pokrvne spríbuznených a na rozličných miestach žijúcich (menších) rodín“ a že „jeden pôvod a jeden jazyk je prirodzenou silou ich príbuzenstva“. V zmysle súdobých nemeckých koncepcií dejín hlásali, že „všetky národy dokopy činia celé človečenstvo, [...] teda šťastie jedného národa nosí šťastie celému ľudstvu; a bieda i nevôľa jedného národa pociťuje sa v celom človečenstve.“3) 1) Autorka je pracovníčkou Historického ústavu SAV v Bratislave. Štúdia vznik- la na Historickom ústave SAV v rámci grantového projektu VEGA č. 2/0138/11 Premeny slovenskej spoločnosti v prvej polovici „dlhého“ 19. storočia. 2) Gdě je sloga, tu je i Božji blagoslov. -

N E W S L E T T

January 2011 Section on Rare Books and Manuscripts N e w s l e t t e r Section's Homepage: http://www.ifla.org/en/rare-books-and-manuscripts Contents People 2 From the Editors 3 76th IFLA General Conference in Gothenburg and Satellite meeting in Uppsala 2010 4 Munich Pre-conference Proceedings 2009 published 6 From the Libraries 9 Exhibitions 17 Events and conferences 34 Projects 38 Publications 43 Web news 49 Cooperation 57 People Chair: Raphaële Mouren Université de Lyon / ENSSIB 17-21, Boulevard du 11 Novembre 1918 69623 VILLEURBANNE, France Tel. +(33)(0)472444343 Fax +(33)(0)472444344 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary and Treasurer: Anne Eidsfeldt The National Library of Norway Post Box 2674 Solli OSLO, NO-0203 Norway Tel. +(47)(23)276095 Fax +(47)(75)121222 E-mail: [email protected] Information Coordinator: Isabel García-Monge Special Collections, Spanish Bibliographical Heritage Union Catalogue, Ministry of Culture C/ Alfonso XII, 3-5, ed. B 28014 MADRID, Spain Tel. +(34) 91 5898805 Fax +(34) 91 5898815 E-mail: [email protected] Editor of the Newsletter: C.C.A.E. (Chantal) Keijsper Division of Special Collections, University Library, Leiden University Witte Singel 27 2311 BG LEIDEN, The Netherlands Tel. +(31)(71)5272832 Fax +(31)(71)5272836 E-mail: [email protected] 2 From the Editors The present edition has been prepared by Chantal Keijsper and Ernst-Jan Munnik (Leiden University Library). The newsletter will only be published in electronic format in future. This gives us the opportunity to include illustrations in the text and thus to enhance the visual attractiveness of the newsletter. -

Nacionalno Samoodreðenje Hrvata I Srba Putem Jezika U Trojednoj Kraljevini Dalmaciji, Hrvatskoj I Slavoniji, 1835

ZGODOVINSKIZGODOVINSKI ^ASOPIS ^ASOPIS • 58 • • 2004 58 • 2004• 3–4 •(130) 3–4 (130)• 377–389 377 Vladislav B. Sotiroviæ Nacionalno samoodreðenje Hrvata i Srba putem jezika u Trojednoj Kraljevini Dalmaciji, Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji, 1835. 1848. g. »Pod nacionalizmom ja æu podrazumevati ideoloki pokret za ostvarivanje i oèuvanje autonomije, jedinstva i identiteta ljudske populacije, èiji ga pojedini pripadnici prihvataju da bi formirali stvarnu ili potencijalnu naciju« »Naciju æu definisati kao ljudsku popu- laciju koja ima ime, istorijsku teritoriju, zajednièki mit i pamæenje, masovnu javnu kulturu, jedinstvenu ekonomiju i obaveze za sve svoje èlanove«, (Smith 1996, 359). »Jugoslavijo na noge pjevaj nek te èuju ko ne sluša pjesmu sluaæe oluju« (iz pesme »Pljuni i zapjevaj moja Jugoslavijo« sa istoimenog albuma sarajevske rok gru- pe Bijelo Dugme). Cilj ovog èlanka je da analitièki istraim glavne tokove i ideoloku osnovu sukoba jezièkih nacionalizama kod Srba i Hrvata na prostorima Provincijala i Vojne krajine Trojedne Kraljevine Hrvatske, Slavonije i Dalmacije od 1835. do 1848. g. U isto vreme je praæena i pojava maða- rizacije ovih prostora putem nametanja maðarskog jezika kao jedinog dravnog (»politièkog«) jezika u èitavoj Kraljevini Ugarskoj. Razlog zašto sam izabrao baš ovaj junoslovenski pro- stor za istraivanje junoslovenskih lingvistièkih nacionalizama je taj što se upravo na terito- riji Trojedne Kraljevine suština nacionalnog odreðenja putem jezika i pisma u gore navede- nom periodu kod Junih Slovena moe najbolje uoèiti, shvatiti i pratiti. Ni na jednom dru- gom prostoru Jugoistoène Evrope sukob dva lingvistièka nacionalizma nije dobio tako jasne crte i imao tako jak uticaj na formiranje nacionalne svesti pojedinih naroda kao što je to bio sluèaj sa Hrvatima i Srbima u Hrvatskoj, Slavoniji i Dalmaciji. -

Bartulin's Tilting at Windmills: Manipulation As A

BARTULIN’S TILTING AT WINDMILLS: MANIPULATION AS A HISTORIOGRAPHIC METHOD (A reply to Nevenko Bartulin’s “Intelectual Discourse on Race and Culture in Croatia 1900-1945”) Tomislav JONJIĆ∗ In this article, which is written in a polemical tone, the author is making an eff ort to problematize a point of view from which the ideology of Croatian nationalism, the Ustasha movement and the Independent State of Croatia are even today being obsereved by a part of historiography. According to the au- thor, the ideology of Croatian nationalism has not suff ered much vital modi- fi cation since the mid-19th century until the end od the Second World War, rather it has kept itself occupied with justifying the right of Croats as a multi- confessional European nation to establish an independent state. Not just po- litical manifestations, but also literary and cultural achievements of the na- tionalist ideology protagonists clearly speak in that direction. Th e geopolitical position of Croatian lands, as well as the infl uence of foreign powers have not made the achievement of such a right of Croatian people and the evolution of Croatian nationalist ideology possible. As a result, that same nationalist ideol- ogy sometimes takes on foreign ideological and political infl uences which are visible only on its surface and purely out of tactial reasons. Th e Ustasha move- ment, being one of the manifestations of Croatian nationalism, is also charac- terized by ideological eclecticism. Th us, diff erent and sometimes contrastive statements made by the leading persona of Ustasha movement regarding their attitude towards the ideologies dominating Europe in the time aft er the First World War are therefore understandable. -

Hungary in the Eighteenth Century 27 István Margócsy

Latin at the Crossroads of Identity Central and Eastern Europe Regional Perspectives in Global Context Series Editors Constantin Iordachi (Central European University, Budapest) Maciej Janowski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw) Balázs Trencsényi (Central European University, Budapest) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cee Latin at the Crossroads of Identity The Evolution of Linguistic Nationalism in the Kingdom of Hungary Edited by Gábor Almási and Lav Šubarić LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Watercolour paintings of senior students at the Debrecen boarding school, taken from the diary of József Csokonai (end of 18th century). Courtesy of Déri Múzeum (Debrecen), Irodalmi Gyűjtemény (K.X.75.72.1). This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1877-8550 isbn 978-90-04-30017-0 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30087-3 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill nv provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, ma 01923, usa.