Anima Eterna Brugge O.L.V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anima Eterna Olv. Jos Van Immerseel

muziek Anima Eterna olv. Jos van Immerseel za 25 mei 2019 / Grote podia / Blauwe zaal 20 uur / pauze ± 20.50 uur / einde ± 22 uur inleiding Stephan Weytjens / 19.15 uur / Blauwe foyer 2018-2019 ken uw klassiekers Freiburger Barockorchester olv. Pablo Heras-Casado Isabelle Faust viool za 22 sep 2018 Le Concert Olympique olv. Jan Caeyers Alexander Melnikov piano vr 15 feb 2019 Camerata Bern olv. Antje Weithaas viool vr 1 mrt 2019 Camerata Salzburg Alexander Lonquich piano do 9 mei 2019 Anima Eterna olv. Jos van Immerseel Jane Gower fagot za 25 mei 2019 teksten programmaboekje Stephan coördinatie programmaboekje deSingel Anima Eterna Weytjens D/2019/5.497/070 Jos van Immerseel muzikale leiding Jane Gower fagot Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Symfonie nr 39 in Es, KV543 29’ Adagio - Allegro Andante con moto Menuetto: Allegro Allegro Concerto voor fagot en orkest in Bes, KV191 20’ Allegro Andante ma Adagio Rondo: Tempo di Minuetto pauze Serenata Notturna in D, KV239 13’ Marcia: Maestoso Menuetto Rondo: Allegretto Symfonie nr 40 in g, KV550 35’ Molto Allegro Andante Menuetto: Allegretto Allegro assai Gelieve uw GSM uit te schakelen Nieuw geluid! De inleidingen kan u achteraf beluisteren via Na een compositiewedstrijd onder studenten van desingel.be het Antwerpse Conservatorium, gecoördineerd door Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling / concert / docent en componist Wim Henderickx, introduceren tentoonstelling van uw keuze. wij 2 nieuwe geluidssignalen in deSingel. Bij de start van een voorstelling hoort u in de Concertvleugels Met bijzondere dank aan Ortwin Wandelgangen een tune van Abel Baeck. Moreau voor het stemmen en het onderhoud van de In de zalen wordt u erop geattendeerd het geluid van concertvleugels van deSingel. -

Happy Birthday, Jos Van Immerseel

zondag 08.11.2015 Happy Birthday, Concertgebouw Jos van Immerseel Anima Eterna Brugge & Jos van Immerseel Schubertiade I. Der Hirt Beste bezoeker, bovendien terug aan de schitterende op maat 14.00 / Kamermuziekzaal gemaakte projecten rond Mozart in 2006, rond Jos van Immerseel, bezieler van ons huisorkest piano- en harpbouwer Erard in 2012, aan de Yeree Suh: sopraan Anima Eterna Brugge, wordt 70 jaar. Het is een fantastische musici die Jos van ver (én nabij!) Lisa Shklyaver: klarinet moment om stil te staan bij een carrière van telkens weer naar Brugge haalt … Chouchane Siranossian: viool een halve eeuw pionierswerk, 50 jaar musiceren Jos van Immerseel, Claire Chevallier: op het allerhoogste niveau. Al ruim dertien jaar De plannen voor de toekomst zijn talrijk en Hammerflügel, kopie naar Conrad Graf (1826) mag het Concertgebouw meeschrijven aan dit ambitieus, er is nog zoveel repertoire dat in door Christopher Clarke succesverhaal, dat – kijk maar naar de tournees de filosofie van Jos en Anima Eterna Brugge (Ruckersgenootschap Antwerpen) van Anima Eterna Brugge dit seizoen – van herontdekt moet worden. En de opgebouwde Brugge tot New York en van Mexico tot expertise moet verder doorsijpelen naar de — Australië reikt. volgende generaties. Daar blijven we samen aan werken. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Tussen de opening op 20.02.2002 met Haydns Impromptu, opus 90 nr. 1, D899/1 (1827) Schöpfung en deze feestelijke Jos-dag Beste Jos, in naam van het hele barst het van de hoogtepunten, zowel in als Concertgebouwteam: van harte proficiat, Franz Schubert buiten de schijnwerpers. In Brugge treedt het en bedankt voor alles; in verleden, heden Vioolsonate in g, D408 (1816) orkest resoluut buiten z’n comfort zone door en toekomst! - Allegro giusto Brahms, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin en Liszt - Andante te verkennen op historische instrumenten. -

Jos Van Immerseel & Claire Chevallier

zo 28.03.2010 Jos van Immerseel & Claire Chevallier Schubert Kamermuziekzaal - 15.00 Biografieën De Franse pianiste Claire Chevallier studeer- Jos van Immerseel (Antwerpen) studeerde de piano aan de conservatoria van Nancy, piano, orgel, klavecimbel, zang en orkestdi- Straatsburg en Parijs en combineerde dit rectie. In 1973 won hij het eerste Concours met studies wiskunde en fysica. Nadien ver- de Clavecin in Parijs. Als docent was hij ver- volgde ze haar muzikale opleiding aan het bonden aan de Schola Cantorum in Bazel, Conservatorium van Brussel bij Jean-Claude het Sweelinck Conservatorium in Amsterdam Vanden Eynden en Guy Van Waas. Tijdens en het Conservatoire Supérieur de Musique haar studies raakte Chevallier via een mas- in Parijs. Zijn ruime interesses brachten hem terclass bij Jos van Immerseel gefascineerd bij de studie van de retoriek, de organologie door historische piano’s. Als musicus-onder- in het algemeen en de historische klavierin- zoeker bezit ze vijf Franse historische piano’s strumenten in het bijzonder. Van Immerseel die de tijdsspanne 1842-1920 bestrijken. bezit een uitgebreide collectie historische Claire Chevallier is een van de artiesten op klavieren, waarmee hij geregeld optreedt. het Parijse label Zig-Zag Territoires en treedt Tot zijn kamermuziekpartners behoren regelmatig op in heel Europa en in Japan, Midori Seiler (viool), Sergei Istomin (cello), als soliste en in kamermuziekverband. Haar Eric Hoeprich (klarinet) en Thomas Bauer interesse voor diverse artistieke disciplines (bariton). Met hen, maar ook als solist en leidde tot projecten met kunstenaars als met zijn ensemble Anima Eterna Brugge Wayn Traub, Josse De Pauw, David nam Jos van Immerseel talloze cd’s op, voor- Claerbout en Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker. -

W E I G O L D & Ö H Jos Van Immerseel M

W E I G O L D & B Ö H Jos van Immerseel M Pianist, Dirigent International Artists & Tours Jos van Immerseel ist Pianist, Dirigent, Forscher, Sammler, Dozent – im Zentrum seines Wirkens und Lebens steht die Musik in ihren vielen Facetten. Seine wichtigsten Lehrer waren Flor Peeters (Orgel und Komposition); Eugeen Traey (Klavier); Jef Alpaerts (Kammermusik); Lucie Frateur (Gesang); Kenneth Gilbert (Cembalo) und Daniël Sternefeld (Dirigent). Außerdem ist Jos van Immerseel Autodidakt in den Bereichen Orgelkunde, Rhetorik, Hammerklavier und Clavichord. 1987 gründete er Anima Eterna Brugge – ein sinfonisches Projektorchester, dessen Musiker auf den Instrumenten spielen, die die Komponisten zu ihrer jeweiligen Zeit gekannt und sie zu ihren Kompositionen inspiriert haben. Seit 2003 residiert Anima im Concertgebouw Brugge. Neben regelmäßigen Auftritten engagiert sich das Ensemble dort auch für Education und nimmt im Concertgebouw seine Alben auf. Van Immerseel lehrte jahrelang an den Konservatorien von Antwerpen, Amsterdam und Paris und war Gastdozent an der Scola Cantorum Basiliensis (Basel), der Indiana University (Bloomington) und dem Kunitachi College (Tokyo). Als Gastdirigent arbeitete er ebenso mit anderen Orchestern, darunter dem Budapest Festival Orchestra, der Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, der Wiener Akademie, dem Orchester des Mozarteums oder dem Beethoven-Orchester Bonn. Darüber hinaus besitzt er eine einzigartige Sammlung historischer Klaviere, die bei seinen Konzerten und CD-Aufnahmen zum Einsatz kommen. Seine Einspielungen sind auf mehr als 120 CDs bei den Labels Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, Channel Classics und dem Label Alpha/Outhere erschienen. Seine jüngste Klavier-Solo- Einspielung war „Piano works oft he young Beethoven“ (2020). Renommierte Magazine wie DER SPIEGEL oder FONO FORUM veröffentlichten ausgezeichnete Kritiken: "Der Belgier nimmt sich zurück und setzt vor allem auf die Wirkung des Hammerflügels anstatt auf technische Showeffekte. -

Mozart Complete Fortepiano Concertos Author: Jed Distler

A1 Mozart Complete Fortepiano Concertos Author: Jed Distler Recorded in 2004-06, this Mozart piano concerto cycle first appeared on the small Pro Musica Camerata laBel. In the main, fortepianist Viviana Sofronitsky (stepdaughter of the legendary Russian pianist Vladimir), conductor Tadeusz Karolak and the Musica Antiqua Collegium Varsoviense offer less consistent satisfaction in comparison with complete period instrument sets from Bilson/ Gardiner/English Baroque Soloists (DG) and Immerseel/Anima Eterna Orchestra (Channel Classics). The strings prove alarmingly uneven: scrawny-toned in K503ʼs Rondo, hideously ill-tuned in K595ʼs first movement, yet firmly focused in the sparsely scored K413, 414 and 415 group and the youthful first four concertos, where Sofronitskyʼs nimBle harpsichord mastery oozes sparkle and wit. However, her fortepiano artistry yields mixed results. Her heavy-handed articulation, pounded out Alberti Basses and crude down-Beat accents roB certain Rondo movements of their prerequisite animation and lilt, such as those in K271, 450, 459, 482 and 595. And when you juxtapose her Brusque, dynamically unvaried treatment of the latterʼs Larghetto with Bilsonʼs graceful lyricism, her faster Basic tempo actually seems slower. Orchestrally speaking, little sense of long line and amorphous melody/ accompaniment textures yield rudderless slow movements in K271 and K456 while, at the same time, the rich contrapuntal writing in the Adagio of K488 could hardly By more viBrant and roBust; the first Bassoonist really shines here and in the Allegro assaiʼs rapid solo licks. Strange how percussively the Busy passagework in the outer movements of the E flat Double Concerto (K365) registers, whereas the more difficult-to-Balance Triple Concerto (K242) Benefits from superior microphone placement. -

ONYX4050.Pdf

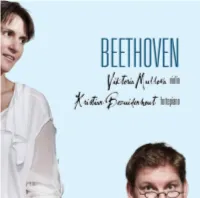

Ludwig van Beethoven LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Violin Sonata no.3 in E flat op.12 no.3 Violinsonate Nr. 3 Es-dur op. 12 Nr. 3 Sonate pour violon et piano no3 en mi bémol majeur op.12 no3 1 I Allegro con spirito 8.20 2 II Adagio con molt’espressione 5.26 3 III Rondo: Allegro molto 4.10 Violin Sonata no.9 in A op.47 ‘Kreutzer’ Violinsonate Nr. 9 A-dur op. 47 „Kreutzer“ Sonate pour violon et piano no9 en la majeur op.47 « Kreutzer » 4 I Adagio sostenuto – Presto – Adagio 13.44 5 II Andante con variazioni 14.13 6 III Presto 8.28 Total timing: 54.34 VIKTORIA MULLOVA violin KRISTIAN BEZUIDENHOUT fortepiano About this recording Although the practice of playing Beethoven violin sonatas on instruments of the composer’s time by now needs no introduction, it still serves as a vivid reminder of just how extraordinary and revolutionary Beethoven’s writing really is. The conductor and fortepianist Jos van Immerseel has remarked that Beethoven’s music sounds paradoxically less modern on the instruments of our time than it does on those of the early 19th century, and indeed, while our hallowed modern counterparts – the Steinway and Stradivarius – are remarkable for their consistency and stability, they seem to have greater difficulty expressing the undeniable volatility and danger of this music. Nowhere is this truer than in the case of the violin sonata – a genre that Beethoven greatly developed – where the composer reveals himself a master of exploiting both the qualities and the idiosyncrasies of the violin and fortepiano. -

Jos Van Immerseel 20.00 Concertzaal 19.15 Inleiding Door Schubert

donderdag 02.05.2013 Jos van Immerseel 20.00 Concertzaal 19.15 Inleiding door Schubert. Klavierwerken Sofie Taes Biografie Uitvoerder en programma Jos van Immerseel (BE) studeerde piano Jos van Immerseel: piano (J.N. Tröndlin, (Eugène Traey), orgel (Flor Peeters), zang Leipzig, ca.1830) (Lucie Frateur) en orkestdirectie (Daniel Sternefeld) en verdiepte zich als autodidact — in organologie, retoriek en de historische pianoforte. Vandaag geniet hij wereldwijd Franz Schubert (1797-1828) erkenning als solist en kamermusicus en is hij 16 Deutsche Tänze, opus 33, D783 (1824) te horen op de belangrijkste internationale concertpodia. Parallel maakte van Immerseel Franz Schubert carrière als dirigent, sinds 1987 van 4 Impromptus, opus 90, D899 (1827) geesteskind Anima Eterna Brugge: een - nr. 1 in c projectorkest met historisch instrumentarium. - nr. 2 in Es Ankerpunten zijn BOZAR, Concertgebouw - nr. 3 in Ges Brugge − waar hij met Anima Eterna Brugge - nr. 4 in As in residentie is sinds 2003 − en de Opéra de Dijon. Van Immerseel realiseerde meer — pauze — dan 100 opnames en cureert sinds 2002 de Collection Anima Eterna voor het label Zig- Franz Schubert Zag Territoires (Outhere). Hij is ten slotte ook Sonate in Bes, D960 (1828) verzamelaar: overtuigd dat de instrumenten - Molto moderato die een componist heeft gekend de sleutel - Andante sostenuto zijn tot een correcte voordracht, bouwde - Scherzo: allegro vivace con delicatezza hij een collectie historische klavieren uit. Zij - Allegro ma non troppo brengen hem tot vlakbij de componist en zijn muziek: een noodzakelijk en compromisloos uitgangspunt. Met de steun van Piano’s Maene FOCUS ANIMA KLAVIER SCHUBERT ETERNA BRUGGE Uw applaus krijgt kleur dankzij de bloemen van Bloemblad. -

AEB Master Class Series 2015

Master Class Series #2: Musicians wanted! Bruges 17-22 August 2015 CONTACT : [email protected] AEB Master Class Series #2 Bruges, 17---22-22 August 2015: MMusiciansusicians wanted!!! Context - Intro The idea to organize a master class rooted in the activities and experience of Anima Eterna Brugge, arose from an assessment of the current status of early music education. Curricula and workshops devoted to ‘Early Music’ are being offered by several institutes, allowing for specialists to pass on their knowledge to a new generation of musicians. While the domain of early music - usually stretching from medieval to 18th-century - is at the center of attention, music from later era’s is usually left out. This is the domain Anima Eterna Brugge has been exploring for over 25 years. As much joy as it has given us to aggregate and internalize these skills and practices, we feel it would be at least equally gratifying to share them and pass them on to the musicians of the future. This is the outset for the Master Class Series, that since 2014 is to be organized yearly by Anima Eterna Brugge in the heart of historical Bruges. Master Class 2015: mix it up! After a first edition for fortepiano, the second AEB Master Class will feature multiple instruments: fortepiano, violin, cello and clarinet. Our partner, the conservatory of Bruges, will be hosting the event again from 17-22 August 2015 . Participants will explore performance practices via 19 th century repertoire of their own choice, alongside Lisa Shklyaver (clarinet), Brian Dean (violin), Stefano Veggetti (cello), Claire Chevallier & Jos van Immerseel (fortepiano) and a range of fortepiano’s from the latter’s collection. -

Schubertiade ‘Du Holde Kunst, Ich Danke Dir’ Anima Eterna Brugge Jos Van Immerseel

SCHUBERTIADE ‘DU HOLDE KUNST, ICH DANKE DIR’ ANIMA ETERNA BRUGGE JOS VAN IMMERSEEL 1 MENU › TRACKLIST › ENGLISH TEXT › TEXTE FRANÇAIS › NEDERLANDSE TEKST › DEUTSCHER TEXT › SUNG TEXTS › TEXTES CHANTÉS › GEZONGEN TEKSTEN › GESUNGENE TEXTE SCHUBERTIADE ‘DU HOLDE KUNST, ICH DANKE DIR’ ANIMA ETERNA BRUGGE JOS VAN IMMERSEEL CD1 1 STÄNDCHEN (ERSTE FASSUNG) D 920 5’29 MEZZO, VOCAL QUARTET, FORTEPIANO 2 AUF DER BRUCK D 853 3’58 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 3 GRETCHEN AM SPINNRADE D 118 3’36 SOPRANO, FORTEPIANO 4 DIE NACHT D 983C 2’42 VOCAL QUARTET 5 MARCHE CARACTÉRISTIQUE D 886/2 6’27 FORTEPIANO* (FOUR HANDS) 6 DIE JUNGE NONNE D 828 4’45 SOPRANO, FORTEPIANO QUINTETT ‘DIE FORELLE’ D 667 VIOLIN, VIOLA, CELLO, DOUBLE BASS, FORTEPIANO* 7 ALLEGRO VIVACE 13’26 8 ANDANTE 7’12 9 SCHERZO 4’32 10 ANDANTINO (THEME & VARIATIONS) 7’47 11 ALLEGRO GIUSTO 7’12 TOTAL TIME: 67’12 CD2 1 NACHTGESANG IM WALDE D 913 6’08 VOCAL QUARTET, HORN QUARTET 2 GANYMED D 544 4’17 SOPRANO, FORTEPIANO 3 DU LIEBST MICH NICHT D 756 3’44 MEZZO, FORTEPIANO 4 ANDANTE (TRIO IN E FLAT MAJOR) D 929/2 10’01 VIOLIN, CELLO, FORTEPIANO* 5 L’INCANTO DEGLI OCCHI D 902/1 2’54 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 6 IL TRADITOR DELUSO D 902/2 3’48 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 7 IL MODO DI PRENDER MOGLIE D 902/3 4’25 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO DIVERTISSEMENT À LA HONGROISE D 818 FORTEPIANO* (FOUR HANDS) 8 ANDANTE 10’54 9 MARCIA, ANDANTE CON MOTO 3’06 10 ALLEGRETTO 13’50 TOTAL TIME: 63’13 CD3 1 FANTASIE IN F MINOR D 940 18’11 FORTEPIANO* ( FOUR HANDS) 2 DER WANDERER D 489 4’55 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 3 NACHT UND TRAÜME D 827 3’46 SOPRANO, -

Franz Schubert

concert n°27 Chapelle Saint-Joseph Dimanche 26 juin 2011 11h00 Franz Schubert Jos van Immerseel / pianoforte www.flaneriesreims.com Pour le bon déroulement des concerts et par respect pour les artistes, nous vous prions de bien vouloir éteindre vos téléphones portables et vous rappelons qu’il est interdit de filmer, d’enregistrer et de prendre des photos durant le concert. Nous vous remercions de votre compréhension. PROGRAMME JOS VAN IMMERSEEL Piano romantique (Piano J.N.Tröndlin, Leipzig, ca. 1830) FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) 16 Deutsche Tänze D.783 (1824) Impromptu en sol bémol majeur, opus 90/3 D.899/3 (1827) Sonate en si majeur, D.960 (1828) Molto moderato Andante sostenuto Scherzo (Allegro vivace con delicatezza) Allegro ma non troppo A PROPOS DU CONCERT 16 Deutsche Tänze D783 Vers les années 1780, le menuet en tant que danse cède la place dans les pays germaniques à la danse allemande, qui s’impose dans les bals de la haute société. Le Deutscher Tanz reflète l’évolution idéologique du moment vers l’égalitarisme : tous les couples unis, se tenant par la main, dansent ensemble en tournant. Son nom est en réalité un terme générique, renvoyant à un ensemble de danses présentant des variantes locales mais unies par des caractéristiques communes. Parmi celles-ci, la plus connue est le ländler, assez lent et rustique. Au tournant des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, « danse allemande » et « valse » sont deux désignations concurrentes. Les Danses allemandes D. 783 de Franz Schubert (1797-1828) permettent de saisir l’évolution du genre dans les années 1820, au moment où l’appellation de « valse » est en train de l’emporter. -

Stanley Ritchie (29.07.-03.08.2019) Violin & Chamber Music with Strings

Individual courses: Stanley Ritchie (29.07.-03.08.2019) Violin & Chamber Music with strings Stanley Ritchie, a pioneer in the Early Music field in America, was born and educated in Australia, graduating from the Sydney Conservatorium of Music in 1956. He left Australia in 1958 to pursue his studies in Paris, where he was a pupil of Jean Fournier, continuing in 1959 to the United States, where he studied with Joseph Fuchs, Oscar Shumsky and Samuel Kissel. In 1963 he was appointed concertmaster of the New York City Opera, and then served as associate concertmaster of the Metropolitan Opera from 1965 to 1970. From 1970 to 1973 he performed as a member of the New York Chamber Soloists, and from 1973 played as Assistant Concertmaster of the Vancouver Symphony until 1975, when he joined the Philadelphia String Quartet (in residence in the University of Washington in Seattle) as first violinist. In 1982 he accepted his current appointment as professor of violin at Indiana University School of Music; in 2016 he was promoted to the rank of Distinguished Professor. His interest in Baroque and Classsical violin dates from 1970 when he embarked on a collaboration with harpsichordist Albert Fuller which led to the founding in 1973 of the Aston Magna summer workshop and festival. In 1974 he joined harpsichordist Elisabeth Wright in forming Duo Geminiani – their 1983 recording of the Bach Sonatas for Violin and Obbligato Harpsichord earned immediate critical acclaim. He has performed with many prominent musicians in the Early Music field, including Hogwood, Gardiner, Bruegghen, Norrington, Bilson and Bylsma, and was for twenty years a member of The Mozartean Players with fortepianist Steven Lubin and cellist Myron Lutzke. -

Flemish Violin Music from Today and the Past

Flemish violin music from today and the past 15 July 2014-20.00 AMUZ, Antwerp A Provincie SABAM AntwerpenP �j�\ CULTURE Programme Sonate nr. 6 opus 1 — Willem Gommaar Kennis (1717-1789) Andante Allegro assai Vioolsonate — Pieter Van Maldere (1729-1768) Fantasie nr. 3 — Peter Benoit (1834-1901) Sonate voor viool en piano — August De Boeck (1865-1937) Spilliaert triptiek — Frits Celis (1929) The eye — Frank Agsteribbe (1968) Violinist: Guido De Neve Cembalist; Frank Agsteribbe Pianist: Jozef De Beenhouwer Kennis and Van Maldere will be played on a ,.Hendrrk Willems" violin, built in Ghent in 1692 (baroque mounting); De Boeck, Celis and Agsteribbe will be played on a .,Mathys Hofmans" violin, built in Antwerp in 1650 (modern mounting). We wish to congratulate composer Frits Celis, who recently turned 851 Be welcome for a drink in the foyer after the concert, offered to you by IAML Antwerp. Guido de Neve is a passionate violinist, who once was dubbed "the new torchbearer of the Belgian violin school'. Already at a very tender age he showed an exceptional musical talent, be- ing admitted to the conservatory of Brussels at eleven. His encounter with the Hungarian violinist Sandor Végh in 1984 had a tremendous impact on his studies and autodidactic ambitions. He developed a very personal style of interpretation, much appreciated at home and abroad. He also enjoys worldwide fame for his research and for the editing of unpublished manuscripts. Guido de Neve performed with the Eugene Isaÿe Ensemble and the Spiegel String Quartet, but later also as a soloist and in duo. Lately he has been applying himself to the baroque violin.