Experiential Shaping of Public Space During Pilgrimage: the Alandi-Pandharpur Palkhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

Ecosystem : an Ecosystem Is a Complete Community of Living Organisms and the Nonliving Materials of Their Surroundings

Solapur: Introduction: Solapur District is a district in Maharashtra state of India. The city of Solapur is the district headquarters. It is located on the south east edge of the state and lies entirely in the Bhima and Seena basins. Facts District - Solapur Area - 14886 km² Sub-divisions - Solapur, Madha (Kurduwadi), Pandharpur Talukas - North Solapur, Barshi, Akkalkot, South Solapur, Mohol,Mangalvedha, Pandharpur, Sangola, Malshiras, Karmala, Madha. Proposal for a separate Phandarpur District The Solapur district is under proposal to be bifurcated and a separate Phandarpur district be carved out of existing Solapur district. Distance from Mumbai - 450 km Means of transport - Railway stations -Solapur, Mohol, Kurduwadi, Madha, Akkalkot Road ST Buses, SMT (Solapur Municipal Transportation, Auto- Rikshaws. Solapur station has daily train service to Mumbai via Pune known as Siddheshwar Express Also, daily shuttle from Solapur to Pune known as Hutatma Express Population Total - 3,849,543(District) The district is 31.83% urban as of 2001. Area under irrigation - 4,839.15 km² Irrigation projects Major-1 Medium-2 Minor-69 Imp. Projs.- Bhima Ujjani Industries Big-98 Small-8986 Languages/dialects - Marathi, Kannada, Telagu Folk-Arts - Lavani, Gondhal, Dhangari,Aradhi and Bhalari songs Weather Temperature Max: 44.10 °C Min: 10.7 °C Rainfall-759.80 mm (Average) Main crops - Jowar, wheat, sugarcane Solapur district especially Mangalwedha taluka is known for Jowar. Maldandi Jowar is famous in all over Maharashtra. In December - January agriculturists celebrates Hurda Party. This is also famous event in Solapur. Hurda means pre-stage of Jowar. Agriculturists sow special breed of Hurda, named as Dudhmogra, Gulbhendi etc. -

Artical Festivals of Maharashtra

ARTICAL FESTIVALS OF MAHARASHTRA. Name- CDT. VEDASHREE PRAVEEN THAKUR. Regimental no.- 1 /MAH/ 20 /SW/ N/ 714445. Institution- BHONSALA MILITARY COLLEGE. INTRODUCTION: It is not possible for each and every citizen to visit different states of India to see their culture and traditions. In Maharashtra, almost all kind of religious diversity are found like Gujrat, South India, Paris and many more. Like every state has it’s speciality, similar Maharashtra has too. When we talk about Maharashtra how can we forget about Maharashtrian people. MAHARASHTRIAN CULTURE: Hindu Marathi people celebrate several festivals during the year. These include Gudi Padwa, Ram Navami, Hanuman Jayanti, Narali Pournima, Mangala Gaur, Janmashtami, Ganeshotsav, Kojagiri Purnima, Makar Sankranti, Diwali, Khandoba Festival, Shivaratri and Holi. Maharashtra had huge influence over India under the 17th-century king Shivaji of the Maratha Empire and his concept of Hindavi Swarajya which translates to self-rule of people. It also has a long history of Marathi saints of Varakari religious movement such as Dnyaneshwar , Namdev , Chokhamela, Eknath and Tukaram which forms the one of bases of the culture of Maharashtra or Marathi culture. FAMOUS FESTIVALS OF MAHARASHTRA: 1. NAG PANCHAMI- Nag Panchali is celebrated in the honour of the Snake God Shesha Nag on the fifth day of the holy month of Shravan. 2. GUDI PADWA- Gudi Padwa is a symbol of victory, characterized by a bamboo stick with a silk cloth. It is garlanded with flowers and has sweets offered to it. 3. NARALI POURNIMA- ‘Narali’ means coconut and ‘pournima' is the full- moon day when offerings of coconuts are made to the Sea- God on this day. -

By Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Doctor of Philosophy) Faculty for Moral and Social Sciences Department Of

“A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES PUNE DISTRICTS, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA” BY Dr. PRATAPRAO RAMGHANDRA DIGHAVKAR, I. P. S. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF VIDYAVACHASPATI (DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY) FACULTY FOR MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDHYAPEETH PUNE JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the entire work embodied in this thesis entitled A STUDY OFECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRILISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES .PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013-2015 has been carried out by the candidate DR.PRATAPRAO RAMCHANDRA DIGHAVKAR. I. P. S. under my supervision/guidance in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such materials as has been obtained by other sources and has been duly acknowledged in the thesis have not been submitted to any degree or diploma of any University or Institution previously. Date: / / 2016 Place: Pune. Dr.Prataprao Ramchatra Dighavkar, I.P.S. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISNTION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES ,PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013—2015 is written and submitted by me at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The present research work is of original nature and the conclusions are base on the data collected by me. To the best of my knowledge this piece of work has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any University or Institution. -

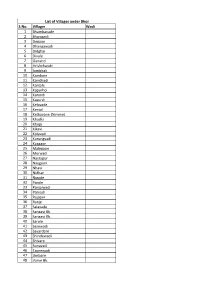

Pmrda Village List

List of Villages under Bhor S.No. Villages Wadi 1 Bhambavade 2 Bhongavli 3 Degaon 4 Dhangawadi 5 Didghar 6 Divale 7 Gunand 8 Hrishchandri 9 Jambhali 10 Kambare 11 Kamthadi 12 Kanjale 13 Kapurhol 14 Karandi 15 Kasurdi 16 Kelavade 17 Kenjal 18 Ketkavane (Nimme) 19 Khadki 20 Khopi 21 Kikavi 22 Kolavadi 23 Kurungvadi 24 Kusgaon 25 Malegaon 26 Morwadi 27 Nasrapur 28 Naygaon 29 Nhavi 30 Nidhan 31 Nigade 32 Pande 33 Panjalwadi 34 Parvadi 35 Rajapur 36 Ranje 37 Salavade 38 Sangavi Bk. 39 Sangavi Kh. 40 Sarole 41 Sasewadi 42 Savardare 43 Shindewadi 44 Shivare 45 Sonavadi 46 Taprewadi 47 Umbare 48 Varve Bk. List of Villages under Bhor S.No. Villages Wadi 49 Varve Kh. 50 Vathar Kh. 51 Velu 52 Virwadi 53 Wagajwadi List of Villages under Daund S.No. Villages Wadi 1 Amoni Mal 2 Bhandgaon 3 Bharatgoan 4 Boratewadi 5 Boriaindi 6 Boribhadak 7 Boripardhi 8 Dahitane 9 Dalimb 10 Dapodi Ekeriwadi 11 Delvadi 12 Deshmukh Mala 13 Devkarwadi 14 Dhaygudewadi 15 Dhumalicha Mala 16 Galandwadi 17 Ganesh Road 18 Handalwadi 19 Jawjebuwachiwadi 20 Kamatwadi 21 Kasurdi 22 Kedgaon 23 Kedgaon Station 24 Khamgaon 25 Khopodi 26 Khutbav 27 Koregaon Bhiwar 28 Ladkatwadi 29 Mirwadi 30 Nandur 31 Nangaon 32 Nathachiwadi 33 Nimbalkar Wasti 34 Panwali 35 Pargaon 36 Patethan 37 Pilanwadi 38 Pimpalgaon 39 Rahu 40 Sahajpurwadi 41 Takali 42 Tambewadi 43 Tamhanwadi 44 Telewadi 45 Undavadi 46 Vadgaon Bande 47 Valki 48 Varwand List of Villages under Daund S.No. Villages Wadi 49 Wakhari 50 Yawat 51 Yawat Station List of Villages under Haveli S.No. -

Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon List of Senate Members

KAVAYITRI BAHINABAI CHAUDHARI NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY, JALGAON LIST OF SENATE MEMBERS List of Senate Members as per provision under Section 28(2) of the Maharashtra Public Universities Act, 2016. a) The Chancellor; Chairperson ; Hon’ble Shri. Bhagat Singh Koshyari, Chancellor, Maharashtra State, Raj Bhavan, Malabar Hill, MUMBAI–400 035. b) The Vice-Chancellor ; Prof. E. Vayunandan, Officiating Vice-Chancellor, Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon, Dist. Jalgaon- 425001 c) The Pro-Vice Chancellor, if any ; Prof. Bhausaheb Vy ankatrao Pawar , Officiating Pro-Vice Chancellor, Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon. Dist. Jalgaon. d) The Deans of Faculties; 1) Prin.Rajendra S. Patil, (Science & Technology) (Acting Dean) PSGVPS’s Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Shahada 2) Prin. Pradipkumar Premsukh Chhajed, (Commerce & Management) (Acting Dean) M. D. Palesha Commerce College, Dhule. 3) Prin. Pramod Manohar Pawar, (Humanities) (Acting Dean) D.M.E.S.Arts College, Amalner. 4) Prin. Ashok Ramchandra Rane, (Inter-disciplinaryStudies) (Acting Dean) K.C.E’s College of Education, Jalgaon & Physical Education, Jalgaon e) The Director of Board of Examinations and Evaluation ; Prof. Kishor Fakira Pawar, Acting Director, Board of Examinations and Evaluation, Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon-425001 Dist. Jalgaon. f) The Finance and Accounts Officer ; Prof. Madhulika Ajay Sonawane , Offg. Financeand Accounts Officer, Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon-425001 Dist. Jalgaon. g) The Directors of Sub-campuses of the university ; Not applicable. Page1 h) The Directors, Innovation, Incubation and Linkages ; Not applicable. i) The Director of Higher Education or his nominee not below the rank of Joint Director ; Dr. Dhanraj Raghuram Mane, Director, Higher Education, Maharashtra State, Central Building, PUNE–411 001. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Operationalising the Agribusiness Infrastructure Development Investment Program- Phase II

FINAL REPORT Operationalising the Agribusiness Infrastructure Development Investment Program- Phase II -Maharashtra- April 2010 Prepared by Client: Asian Development Bank OPERATIONALISING THE AGRIBUSINESS INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT INVESTMENT PROGRAM- PHASE II FINAL REPORT Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Project outline and intent 1 1.1.1 Value Chain approach 1 1.1.2 Hub and Spoke model 2 1.2 Integrated value Chain Regions 3 1.2.1 Agri‐Marketing and Infrastructure 3 1.2.2 Selection of Regions 3 1.3 Methodology 4 1.4 Structure of the Report 9 Nashik Integrated Value Chain 10 2 Focus crop: Pomegranate 12 2.1 Value chain analysis 13 2.1.1 Trade channel of pomegranate 13 2.1.2 Price build up along the value chain of pomegranate 16 2.2 Infrastructure Assessment 18 2.2.1 Post harvest Infrastructure 18 2.2.2 Marketing Infrastructure 18 2.3 Gaps identified in the value chain 18 2.4 Potential for Intervention 19 3 Focus crop: Grape 20 3.1 Value Chain Analysis 21 3.1.1 Trade channel of Grapes 21 3.1.2 Price build up along the value chain of Grapes 24 3.2 Wineries 25 3.3 Export of Grapes 26 3.4 Infrastructure Assessment 28 3.4.1 Post Harvest/Marketing Infrastructure 28 3.4.2 Institutional Infrastructure 28 3.5 Gaps in the value chain 29 3.6 Proposed Interventions 30 4 Focus Crop: Banana 31 4.1 Value Chain Analysis 33 4.1.1 Existing Post Harvest Infrastructure and Institutional Mechanism 38 4.2 Gaps in the value chain and potential interventions 42 5 Focus crop: Onion 44 5.1 Value chain analysis 45 5.1.1 Trade channel of Onion 45 5.1.2 Price -

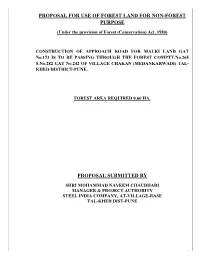

Proposal for Use of Forest Land for Non-Forest Purpose

PROPOSAL FOR USE OF FOREST LAND FOR NON-FOREST PURPOSE (Under the provision of Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980) CONSTRUCTION OF APPROACH ROAD FOR MALKI LAND GAT No.173 IS TO BE PASSING THROUGH THE FOREST COMPTT.No.265 S.No.282 GAT No.242 OF VILLAGE CHAKAN (MEDANKARWADI) TAL- KHED DISTRICT-PUNE. FOREST AREA REQUIRED 0.60 HA. PROPOSAL SUBMITTED BY SHRI MOHAMMAD NAYEEM CHAUDHARI MANAGER & PROJECT AUTHORITY STEEL INDIA COMPANY, AT-VILLAGE-RASE TAL-KHED DIST-PUNE 1 Reference: Index Sr. No.1 APPENDIX (See rule 6) FORM – A Form for seeking prior approval under section 2 of F.C.A.1980.Proposal by State Government and other Authorities (See Rule 6) PART – I (To be filled up by user agency) 1. Project Details:- I) Short narrative of the Purpose:- Proposal for construction of approach proposal and project / road for Steel India Company Gat No.174 At- scheme for which the forest land is required. Village- Rase Tal-Khed, Dist- Pune. Our land bearing Gat No. 174 is in village Rase. The Gat No. 174 and other nearby area is proposed for Small Scale industry by Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation and this area is adjacent to the industrial Zone. Therefore we have established our plant for machinery work and threading work company over here. But there is no road facility available for transportation of raw material and vehicle. Our company Gat No. 174 is near Chakan Alandi main road. The existing Chakan-Alandi main road passes through Reserved forest land of Village Chakan (Medankarwadi) which is adjacent to Gayran revenue land Gat No. -

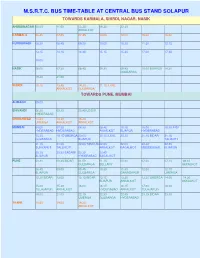

M.S.R.T.C. Bus Time-Table at Central Bus Stand Solapur

M.S.R.T.C. BUS TIME-TABLE AT CENTRAL BUS STAND SOLAPUR TOWARDS KARMALA, SHIRDI, NAGAR, NASIK AHMEDNAGAR 08.00 11.00 13.25 16.30 22.30 AKKALKOT KARMALA 06.45 07.00 07.45 10.00 12.00 15.30 16.00 KURDUWADI 08.30 08.45 09.20 10.00 10.30 11.30 12.15 13.15 14.15 14.45 15.15 15.30 17.00 17.45 18.00 NASIK 06.00 07.30 08.45 09.30 09.45 10.00 BIJAPUR 14.30 GULBARGA 19.30 21.00 SHIRDI 10.15 13.45 14.30 21.15 ILKAL AKKALKOT GULBARGA TOWARDS PUNE, MUMBAI ALIBAGH 09.00 BHIVANDI 06.30 09.30 20.45 UDGIR HYDERABAD CHINCHWAD 13.30 14.30 15.30 UMERGA AKKALKOT AKKALKOT MUMBAI 04.00 07.30 08.30 08.45 10.15 15.00 15.30 INDI HYDERABAD HYDERABAD AKKALKOT BIJAPUR HYDERABAD 15.30 19.15 UMERGA 20.00 20.15 ILKAL 20.30 21.15 BIDAR 21.15 GULBARGA BIJAPUR TALIKOTI 21.15 21.30 22.00 TANDUR 22.00 22.00 22.30 22.45 SURYAPET TALLIKOTI AKKALKOT BAGALKOT MUDDEBIHAL BIJAPUR 23.15 23.30 BADAMI 23.30 23.45 BIJAPUR HYDERABAD BAGALKOT PUNE 00.30 00.45 BIDAR 01.00 01.15 05.30 07.00 07.15 08.15 GULBARGA BELLARY AKKALKOT 08.45 09.00 09.45 10.30 11.30 12.00 12.15 BIJAPUR GULBARGA GANAGAPUR UMERGA 12.30 BIDAR 13.00 13.15 BIDAR 13.15 13.30 13.30 UMERGA 14.00 14.30 BIJAPUR AKKALKOT AKKALKOT 15.00 15.30 16.00 16.15 16.15 17.00 18.00 TULAJAPUR AKKALKOT HYDERABAD AKKALKOT TULAJAPUR 19.00 21.00 22.15 22.30 22.45 23.15 BIDAR 23.30 UMERGA GULBARGA HYDERABAD THANE 10.45 19.00 19.30 AKKALKOT TOWARDS AKKALKOT, GANAGAPUR, GULBARGA AKKALKOT 04.15 05.45 06.00 08.15 09.15 09.15 10.30 10.45 11.00 11.30 11.45 12.15 13.45 14.15 15.30 16.00 16.30 16.45 17.00 GULBARGA 02.00 PUNE 05.15 06.15 07.30 08.15 -

Oraşe Inteligente – Experienţă Şi Practică La Nivel Internaţional

Rode S. mrp.ase.ro DRINKING WATER SUPPLY MANAGEMENT THROUGH PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN MUNICIPAL COUNCILS OF PUNE DISTRICT ISSN MANAGEMENT RESEARCH AND PRACTICE VOL. 6 ISSUE 1 (2014) PP: 79-98 2067- 2462 DRINKING WATER SUPPLY MANAGEMENT THROUGH PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN MUNICIPAL COUNCILS OF PUNE DISTRICT Sanjay RODE S.K.Somaiya college , University of Mumbai , India [email protected] Abstract Drinking water demand is rising in Municipal Councils of Pune district. Population is continuously increasing because of industrialization, service sector growth and change in lifestyle. People demand safe drinking water for different purposes such as cooking, cleaning, washing cloth. There is need to provide safe, reliable and consistent drinking water in all municipal councils. Municipal councils must invest more money in storage and distribution of drinking water supply. Water supply connections in each municipal council are less in terms of total households and commercial units. The recovery of water bills is very low in all municipal councils. Therefore there is less revenue generated from water supply system. All municipal councils should have modern water supply system to resolve different issues at different levels. There is need of public participation in drinking water supply in all municipal councils. Public awareness of water use will save more drinking water. Keywords: Water distribution, Storage, equality 1. INTRODUCTION Water is a basic necessity of human being. Therefore it is responsibility of government to provide drinking water to whole population. India has undoubtedly made some impressive gains in providing Volume 6 Issue 1 / March March 2014 / Issue 1 6 Volume drinking water to its population compared to the situation at independence. -

Review of Research Journal:International Monthly Scholarly

ISSN 2249-894X Impact Factor : 3.1402 (UIF) Volume - 5 | Issue - 3 | Dec - 2015 Review Of Research _________________________________________________________________________________ SOCIAL AUDIT OF NATIONAL RURAL EMPLOYMENT GUARANTEE SCHEME IN SOLAPUR DISTRICT Dr. S. V. Shinde Associate Professor , D. A. V. Velankar College of Commerce, Solapur. ABSTRACT : INTRODUCTION : National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (or, NREGA The act was first No 42, later renamed as the "Mahatma Gandhi National Rural proposed in 1991 by Narasimha Employment Guarantee Act", MGNREGA), is an Indian labour law Rao. In 2006, it was finally and social security measure that aims to guarantee the 'right to work'. accepted in the parliament and It aims to enhance livelihood security in rural areas by commenced implementation in providing at least 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to 200 districts of India. Based on every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled this pilot experience, NREGA manual work. was scoped up to covered all the districts of India from 1 April 2008. The MGNREGA was initiated with the objective of "enhancing livelihood security inrural areas by providing at least 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year, to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work". Another aim of MGNREGA is to create durable assets (such as roads, canals, ponds, wells). Employment is to be provided within 5 km of an applicant's residence, and minimum wages are to be paid. If work is not provided within 15 days of applying, applicants are entitled to an unemployment allowance. Thus, employment under MGNREGA is a legal entitlement.