Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary Books on the Related Theme by the Same Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dharma. India World...1.Rtf

DHARMA, INDIA AND THE WORLD ORDER TWENTY-ONE ESSAYS i ii DHARMA, INDIA AND THE WORLD ORDER TWENTY-ONE ESSAYS CHATURVEDI BADRINATH iii Copyright 1993 by Chaturvedi Badrinath First published 1993 by Pahl-Rugenstein and Saint Andrew Press. Pahl-Rugenstein Verlag Nachfolger GmbH BreiteStr.47 D-53111 Bonn Tel (0228) 63 23 06 Fax (0228) 63 49 68 Bundesrepublik Deutschland ISBN 3-89144-179-7 Saint Andrew Press 121 George Street Edinburgh EH2 4YN Scotland, UK Tel (031) 22 55 72 2 Fax (031) 22 03 113 ISBN 0-86513-172-8 Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Badrinath, Chaturvedi: Dharma, India, and the world order: twenty-one essays Chaturvedi Badrinath. - Edinburgh: Saint Andrew Press; Bonn: Pahl-Rugenstein, 1993 ISBN 3-89144-179-7 (Pahl-Rugenstein) ISBN 0-86153-172-8 (Saint Andrew Press) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Typeset by Tulika Print Communication Services Pvt. Ltd. C-20, Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi 110016 Printed in Hungary by Interpress iv To Bishop Lesslie Newbigin To whose friendship I owe much v vi CONTENTS Foreword ix Preface xv Acknowledgements xvii To the Reader xxv An Outline of the Inquiry and Arguments in the Twenty-one Essays 3 Twenty-one Essays 1 Hindus and Hinduism: Wrong Labels Given By Foreigners 19 2 Search for Dharma: Problems Stemming from Travesties 24 3 Understanding India: Key to Reform of Society 29 4 Limits to Political Power: Traditional Indian Precepts 34 5 Dharma is not 'Religion': Misconception Has to Be -

2020 Religious Calendar

January 2020 Date Observance Monday 6th Putrada Ekadashi (starts from 4:38 p.m Sun 5th . ends 5:55 p.m. Mon 6th) Friday 10th Purnima (ends 2:22 p.m.) Monday 13th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Tuesday 14th Makar Sankranti/Pongal Monday 20th Shattila Ekadashi (starts 4:22 p.m. Sun. ends 3:37 p.m. Mon 20th ) Friday 24th Amavasya (ends 4:43 p.m.) Wednesday 29th Vasant Panchami/ Saraswati Jayanti February 2020 Date Observance Wednesday 5th Jaya Ekadashi (starts 11:21 a.m. Tues. ends 11:02 a.m. Wed. 5th ) Saturday 8th Purnima (ends 2:34 a.m. Sunday) Tuesday 11th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Tuesday 18th Vijaya Ekadashi (starts 4:04 a.m. Tues. ends 4:33 a.m. Wednesday) Friday 21st Maha Shiva Raatri Sunday 23rd Amavasya (ends 10:33 a.m.) March 2020 Date Observance Thursday 5th Amalaki Ekadashi (starts 2:50 a.m. Thu. ends 1:18 a.m Friday) Sunday 8th Holika Dahan Monday 9th Purnima/ Holi (ends 1:48 p.m.) note Holi is celebrated after Purnima ends Thursday 12th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Thursday 19th Paapmochinin Ekadashi (starts 6:57 p.m. Wed. ends 8:31 p.m. Thu.) Monday 23rd Amavasya (ends 5:29 a.m. Tuesday) Tuesday 24th Vasant NavRatri Begins April 2020 Date Observance Wednesday 1st Shri Durga Ashtami Thursday 2nd Shri Ram Navmi Saturday 4th Kamada Ekadashi (starts 3:29 p.m. Fri. ends 1:01 p.m. Sat.) Tuesday 7th Purnima/Shri Hanuman Jayanti (ends 10:36 p.m.) Friday 10th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Saturday 18th Varuthini Ekadashi (starts 10:35 a.m. -

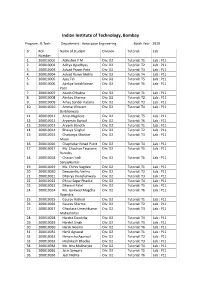

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

How Chinmaya Mission Trains Leaders

e d u cati o N How Chinmaya Mission Trains Leaders The two-year Vedanta course at Sandeepany Sadhanalaya in Mumbai demands rigorous personal discipline, deep devotion and intense scriptural study Chinmaya Mission’s training program is practice. Here the acharyas (teachers) of no ordinary course of study. It is a 24/7 Chinmaya Mission are trained in a two-year commitment of body, mind and soul to an program which begins and ends on Ganesha immersive spiritual adventure. A recent Chathurti. A year later, a new course begins. graduate, Acharya Vivek, recounts his I was honored to join the 13th course, which extraordinary experience. commenced in 2005. I was born and raised in Niagara Falls, By Acharya Vivek, Canada, to devotees of Swami Tejomayanan- Chinmaya Mission da, the current head of Chinmaya Mission. I Niagara, Canada pursued all that any young Canadian would: ome great men try to improve the higher education, travelling, fancy posses- world by changing the outer settings sions. Like everyone else, I followed these of economic and societal conditions. pursuits for the sake of happiness. And like S A few greater men try to change the everyone else, happiness eluded me—time processes and the vision of the masses. The and time again. This was an intensely tiring very greatest achieve a complete and last- period of my life. ing transformation, one individual at a time. Relief came from a most unexpected That was Swami Chinmayananda’s vision source. I had learned that Swami Tejoma- when he created Sandeepany Sadhanalaya yananda himself was going to be the Resi- in 1963. -

Satsang Sandesh

Satsang Sandesh India Temple Association, Inc. Hindu Temple, 25 E. Taunton Ave, Berlin, NJ 08009 SOUTH JERSEY ♦ DELAWARE ♦ PENNSYLVANIA (Non-Profit Tax Exempt Organization, Tax ID # 22-2192491) Vol. 58 No. 1 Phone: (855) MYMANDIR (855-696-2634) www.indiatemple.org JUNE 2015 Religious Calendar 30TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF June 7 Sunday PRAN-PRATISHTHA Graduation Day—Pooja in Mandir SAVE THESE DATES June 2 Tuesday SEPTEMBER 11, 12, 13, 2015 Vatapournima / Satyana- From the pages of history: Although ITA was formed in 1975, and a parcel of rayan Katha land was purchased in Lindenwold, it lacked the funds to construct a temple. It was June 12 Friday Lord Krishna’s divine grace that enabled our active members to merge and bring the Yogini Ekadashi assets of Shri Vallabhnidhi with ITA to purchase the existing property for our temple. June 17 Wednesday On May 6, 1982 we purchased the church property and the Hindu Mandir in Berlin Adhik Aashadh / Adhik became a reality, a place of worship for all Hindus in the Delaware Valley. Purushottam Mas Shri Narendra Amin was instrumental in providing the paintings for the temple beauti- June 28 Sunday fication as well as the meticulous details associated with the ordering of the idols from Kamala Ekadashi India. On May 31, 1985, the Idols of Radha-Krishna arrived at the Mandir. However, because of in-transit damage to Radhaji’s idol, the Pran-Pratishtha Mahotsava of Lord Monthly Activities Krishna was performed on September 20, 21 and 22, 1985. Over the past 30 years, the Kshama Raghuveer 707- temple and its services have grown along with the community. -

Vol. 30, No.6 November/December 2019

Vol. 30, No.6 November/December 2019 A CHINMAYA MISSION SAN JOSE PUBLICATION MISSION STATEMENT To provide to individuals, from any background, the wisdom of Vedanta and practical means for spiritual growth and happiness, enabling them to become a positive contributor to the society. TheC particularhinmaya form that the L greatahari Lord took in the name of Sri Swami Tapovanam has dissolved, and he has gone back to merge into his own Nature. He has now become the Essence in each one of us. Wherever we find the glow of divine compassion, love, purity, and brilliance, there we see Sri Gurudev (Swami Tapovanji) with his ever-smiling face. He has left his sheaths. He has now become the Self in all of us. Ours is a great responsibility. It is not sufficient that only we ourselves evolve–we must learn to release him to visible expression everywhere. It is a glorious chance to take a sacred oath that we shall not rest contented until he is fulfilled. SWAMI CHINMAYANANDA from My Teacher, Swami Tapovanam CONTENTS Volume 30 No. 6 November/December 2019 From The Editors Desk . 2 Chinmaya Tej Editorial Staff . 2 We Stand as One Family . 3 The Glory of Saṁnāsa . 10 The Ethos of Spirituality . 13 Friends of Swami Chinmayananda . 20 Tapovan Prasad . 21 Chinmaya Study Groups . 22 Adult Classes at Sandeepany . 23 Shiva Abhisheka & Puja . 23 Bala Vihar/Yuva Kendra & Language Classes . 24 Gita Chanting Classes for Children . 25 Vedanta Study Groups - Adult Sessions . 26 Swaranjali Youth Choir . 28 BalViHar Magazine . 29 Community Outreach Program . 30 Receptivity . -

Tathagata-Garbha Sutra

Tathagata-garbha Sutra (Tripitaka No. 0666) Translated during the East-JIN Dynasty by Tripitaka Master Buddhabhadra from India Thus I heard one time: The Bhagavan was staying on Grdhra-kuta near Raja-grha in the lecture hall of a many-tiered pavilion built of fragrant sandalwood. He had attained buddhahood ten years previously and was accompanied by an assembly of hundred thousands of great bhikshus and a throng of bodhisattvas and great beings sixty times the number of sands in the Ganga. All had perfected their zeal and had formerly made offerings to hundred thousands of myriad legions of Buddhas. All could turn the Irreversible Dharma Wheel. If a being were to hear their names, he would become irreversible in the unsurpassed path. Their names were Bodhisattva Dharma-mati, Bodhisattva Simha-mati, Bodhisattva Vajra-mati, Bodhisattva Harmoniously Minded, bodhisattva Shri-mati, Bodhisattva Candra- prabha, Bodhisattva Ratna-prabha, Bodhisattva Purna-candra, Bodhisattva Vikrama, Bodhisattva Ananta-vikramin, Bodhisattva Trailokya-vikramin, Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva Maha-sthama-prapta, Bodhisattva Gandha-hastin, Bodhisattva Sugandha, Bodhisattva Surpassing Sublime Fragrance, Bodhisattva Supreme matrix, Bodhisattva Surya-garbha, Bodhisattva Ensign Adornment, Bodhisattva Great Arrayed Banner, Bodhisattva Vimala-ketu, Bodhisattva Boundless Light, Bodhisattva Light Giver, Bodhisattva Vimala-prabha, Bodhisattva Pramudita-raja, Bodhisattva Sada-pramudita, Bodhisattva Ratna-pani, Bodhisattva Akasha-garbha, Bodhisattva King of the Light -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

A) Karma – Phala – Prepsu : (Ragi) • One Who Has Predominate Desire for Result of Action for Veidica Or Laukika Karma

BHAGAVAD GITA Chapter 18 Moksa Sannyasa Yoga (Final Revelations of the Ultimate Truth) 1 Chapter 18 Moksa Sannyasa Yoga (Means of Liberation) Summary Verse 1 - 12 Verse 18 - 40 Verse 50 - 55 Verse 63 - 66 - Difference Jnana Yoga - Final Summary 3 Types of : between (Meditation) - Be my devotee 1) Jnanam – Knowledge Sannyasa + Tyaga. be my worshipper 2) Karma – Action surrender to me 3) Karta – Doer - Being established and do your duty. Verse 13 - 17 4) Buddhi – Intellect in Brahman’s 5) Drithi – will Nature he becomes 6) Sukham – Happiness free from Desire. Verse 67 - 73 Jnana Yoga Verse 56 - 62 Verse 41 - 49 - Lords concluding - 5 factors in all remarks. actions. Karma Yoga - Body, Prana, Karma Yoga (Svadharma) (Devotion) Mind, Sense Verse 74 - 78 organs, Ego + - Purified seeker who Presiding dieties. - Constantly is detached and self - Sanjayas remember Lord. controlled attains Conclusion. Moksa 2 Introduction : 1) Mahavakya – Asi Padartham 3rd Shatkam Chapter 13, 14, 15 Chapter 16, 17 Chapter 18 - Self knowledge. - Values to make mind fit - Difference between for knowledge. Sannyasa and Tyaga. 2) Subject matter of Gita Brahma Vidya Yoga Sastra - Means of preparing for - Tat Tvam Asi Brahma Vidya. - Identity of Jiva the - Karma in keeping with individual and Isvara the dharma done with Lord. proper attitude. - It includes a life of renunciation. 3 3) 2 Lifestyles for Moksa Sannyasa Karma Renunciation Activity 4) Question of Arjuna : • What is difference between Sannyasa (Renunciation) and Tyaga (Abandonment). Questions of Arjuna : Arjuna said : If it be thought by you that ‘knowledge’ is superior to ‘action’, O Janardana, why then, do you, O Kesava, engage me in this terrible action? [Chapter 3 – Verse 1] With this apparently perplexing speech you confuse, as it were, my understanding; therefore, tell me that ‘one’ way by which, I, for certain, may attain the Highest. -

Ramayana of * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH with EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY

THE Ramayana OF * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH WITH EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY (. ^ ^reenivasa jHv$oiu$ar, B. A., LECTURER S. P G. COLLEGE, TRICHINGj, Balakanda and N MADRAS: * M. K. PEES8, A. L. T. PRKS8 AND GUARDIAN PBE8S. > 1910. % i*t - , JJf Reserved Copyright ftpfiglwtd. 3 [ JB^/to PREFACE The Ramayana of Valmeeki is a most unique work. The Aryans are the oldest race on earth and the most * advanced and the is their first ; Ramayana and grandest epic. The Eddas of Scandinavia, the Niebelungen Lied of Germany, the Iliad of Homer, the Enead of Virgil, the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso of Dante, the Paradise Lost of Milton, the Lusiad of Camcens, the Shah Nama of Firdausi are and no more the Epics ; Ramayana of Valmeeki is an Epic and much more. If any work can clam} to be the Bible of the Hindus, it is the Ramayana of Valmeeki. Professor MacDonell, the latest writer on Samskritha Literature, says : " The Epic contains the following verse foretelling its everlasting fame * As long as moynfain ranges stand And rivers flow upon the earth, So long will this Ramayana Survive upon the lips of men. This prophecy has been perhaps even more abundantly fulfilled than the well-known prediction of Horace. No pro- duct of Sanskrit Literature has enjoyed a greater popularity in India down to the present day than the Ramayana. Its story furnishes the subject of many other Sanskrit poems as well as plays and still delights, from the lips* of reciters, the hearts of the myriads of the Indian people, as at the 11 PREFACE great annual Rama-festival held at Benares.