Horn Use in Triceratops (Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae): Testing Behavioral Hypotheses Using Scale Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Neoceratopsian Dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia And

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01222-7 OPEN A neoceratopsian dinosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia and the early evolution of ceratopsia ✉ Congyu Yu 1 , Albert Prieto-Marquez2, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig 3,4, Zorigt Badamkhatan4,5 & Mark Norell1 1234567890():,; Ceratopsia is a diverse dinosaur clade from the Middle Jurassic to Late Cretaceous with early diversification in East Asia. However, the phylogeny of basal ceratopsians remains unclear. Here we report a new basal neoceratopsian dinosaur Beg tse based on a partial skull from Baruunbayan, Ömnögovi aimag, Mongolia. Beg is diagnosed by a unique combination of primitive and derived characters including a primitively deep premaxilla with four pre- maxillary teeth, a trapezoidal antorbital fossa with a poorly delineated anterior margin, very short dentary with an expanded and shallow groove on lateral surface, the derived presence of a robust jugal having a foramen on its anteromedial surface, and five equally spaced tubercles on the lateral ridge of the surangular. This is to our knowledge the earliest known occurrence of basal neoceratopsian in Mongolia, where this group was previously only known from Late Cretaceous strata. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that it is sister to all other neoceratopsian dinosaurs. 1 Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York 10024, USA. 2 Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, ICTA-ICP, Edifici Z, c/de les Columnes s/n Campus de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès Sabadell, Barcelona, Spain. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA. 4 Institute of Paleontology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, ✉ Ulaanbaatar 15160, Mongolia. -

MEET the DINOSAURS! WHAT’S in a NAME? a LOT If You Are a Dinosaur!

MEET THE DINOSAURS! WHAT’S IN A NAME? A LOT if you are a dinosaur! I will call you Dyoplosaurus! Most dinosaurs get their names from the ancient Greek and Latin languages. And I will call you Mojoceratops! And sometimes they are named after a defining feature on their body. Their names are made up of word parts that describe the dinosaur. The name must be sent to a special group of people called the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to be approved! Did You The word DINOSAUR comes from the Greek word meaning terrible lizard and was first said by Know? Sir Richard Owen in 1841. © 2013 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® | 3 SEE IF YOU CAN FIND OUT THE MEANING OF SOME OF OUR DINOSAUR’S NAMES. Dinosaur names are not just tough to pronounce, they often have meaning. Dinosaur Name MEANING of Dinosaur Name Carnotaurus (KAR-no-TORE-us) Means “flesh-eating bull” Spinosaurus (SPY-nuh-SORE-us) Dyoplosaurus (die-o-pluh-SOR-us) Amargasaurus (ah-MAR-guh-SORE-us) Omeisaurus (Oh-MY-ee-SORE-us) Pachycephalosaurus (pak-ee-SEF-uh-low-SORE-us) Tuojiangosaurus (toh-HWANG-uh-SORE-us) Yangchuanosaurus (Yang-chew-ON-uh-SORE-us) Quetzalcoatlus (KWET-zal-coe-AT-lus) Ouranosaurus (ooh-RAN-uh-SORE-us) Parasaurolophus (PAIR-uh-so-ROL-uh-PHUS) Kosmoceratops (KOZ-mo-SARA-tops) Mojoceratops (moe-joe-SEH-rah-tops) Triceratops (try-SER-uh-TOPS) Tyrannosaurus rex (tuh-RAN-uh-SORE-us) Find the answers by visiting the Resource Library at Carnotaurus A: www.OmahaZoo.com/Education. Search word: Dinosaurs 4 | © 2013 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® DINO DEFENSE All animals in the wild have to protect themselves. -

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Basal Ornithischia (Reptilia, Dinosauria)

A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE BASAL ORNITHISCHIA (REPTILIA, DINOSAURIA) Marc Richard Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2007 Committee: Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor Don C. Steinker Daniel M. Pavuk © 2007 Marc Richard Spencer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor The placement of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus and the Heterodontosauridae within the Ornithischia has been problematic. Historically, Lesothosaurus has been regarded as a basal ornithischian dinosaur, the sister taxon to the Genasauria. Recent phylogenetic analyses, however, have placed Lesothosaurus as a more derived ornithischian within the Genasauria. The Fabrosauridae, of which Lesothosaurus was considered a member, has never been phylogenetically corroborated and has been considered a paraphyletic assemblage. Prior to recent phylogenetic analyses, the problematic Heterodontosauridae was placed within the Ornithopoda as the sister taxon to the Euornithopoda. The heterodontosaurids have also been considered as the basal member of the Cerapoda (Ornithopoda + Marginocephalia), the sister taxon to the Marginocephalia, and as the sister taxon to the Genasauria. To reevaluate the placement of these taxa, along with other basal ornithischians and more derived subclades, a phylogenetic analysis of 19 taxonomic units, including two outgroup taxa, was performed. Analysis of 97 characters and their associated character states culled, modified, and/or rescored from published literature based on published descriptions, produced four most parsimonious trees. Consistency and retention indices were calculated and a bootstrap analysis was performed to determine the relative support for the resultant phylogeny. The Ornithischia was recovered with Pisanosaurus as its basalmost member. -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

New Book Catalog

New Book Catalog www.doverpublications.com Winter 2020 Connect with us! New Books for a OVER 50 NEW TITLES! New Year! Save 25% on 50 Favorites! Take an Additional $10 Off & Free Shipping See pages 46–47 See page 2 New Book Q1 2020 01-09.indd 1 12/5/19 11:03 AM 2020: New Year, New You $10 off your order of $40 or more TO REDEEM: When ordering by mail or fax, please IXIA PRESS NEW! enter the coupon code in the title column on the last Named after the South African flower that represents happiness, line of the order form. When ordering online, enter the Ixia Press presents inspiring books on leadership, business, spirituality, NEW! coupon code during checkout. and wellness that foster a spirit of personal and professional growth PLEASE NOTE: You must provide the Coupon Code Use to receive your discount. Orders must be received by and exploration. The imprint combines completely original works with seminal February 22, 2020. Shipping and handling, taxes, Coupon and gift certificates do not apply toward the classics given a fresh new lease on life, all written by some of the most respected Code purchase requirement. We reserve the right to change or discontinue this offer at any time. Your authors in their fields. merchandise total after your coupon deduction must CNWC be $50 or more to be eligible for Free Shipping. Can’t be combined with any other coupon. Reader-friendly handbook is structured around the ways in which crystals can Offer Ends 2/22/20 be used to improve specifi c life areas HIGHLIGHTS Valentine’s Day . -

A Revision of the Ceratopsia Or Horned Dinosaurs

MEMOIRS OF THE PEABODY MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME III, 1 A.R1 A REVISION orf tneth< CERATOPSIA OR HORNED DINOSAURS BY RICHARD SWANN LULL STERLING PROFESSOR OF PALEONTOLOGY AND DIRECTOR OF PEABODY MUSEUM, YALE UNIVERSITY LVXET NEW HAVEN, CONN. *933 MEMOIRS OF THE PEABODY MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY YALE UNIVERSITY Volume I. Odontornithes: A Monograph on the Extinct Toothed Birds of North America. By Othniel Charles Marsh. Pp. i-ix, 1-201, pis. 1-34, text figs. 1-40. 1880. To be obtained from the Peabody Museum. Price $3. Volume II. Part 1. Brachiospongidae : A Memoir on a Group of Silurian Sponges. By Charles Emerson Beecher. Pp. 1-28, pis. 1-6, text figs. 1-4. 1889. To be obtained from the Peabody Museum. Price $1. Volume III. Part 1. American Mesozoic Mammalia. By George Gaylord Simp- son. Pp. i-xvi, 1-171, pis. 1-32, text figs. 1-62. 1929. To be obtained from the Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn. Price $5. Part 2. A Remarkable Ground Sloth. By Richard Swann Lull. Pp. i-x, 1-20, pis. 1-9, text figs. 1-3. 1929. To be obtained from the Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn. Price $1. Part 3. A Revision of the Ceratopsia or Horned Dinosaurs. By Richard Swann Lull. Pp. i-xii, 1-175, pis. I-XVII, text figs. 1-42. 1933. To be obtained from the Peabody Museum. Price $5 (bound in cloth), $4 (bound in paper). Part 4. The Merycoidodontidae, an Extinct Group of Ruminant Mammals. By Malcolm Rutherford Thorpe. In preparation. -

A Subadult Individual of Styracosaurus Albertensis

Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology 8:67–95 67 ISSN 2292-1389 A subadult individual of Styracosaurus albertensis (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) with comments on ontogeny and intraspecific variation inStyracosaurus and Centrosaurus Caleb M. Brown1,*, Robert B. Holmes2, Philip J. Currie2 1Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Box 7500, Drumheller, AB, T0J 0Y0, Canada; [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2E9, Canada; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: Styracosaurus albertensis is an iconic centrosaurine horned dinosaur from the Campanian of Alberta, Canada, known for its large spike-like parietal processes. Although described over 100 years ago, subsequent dis- coveries were rare until the last few decades, during which time several new skulls, skeletons, and bonebeds were found. Here we described an immature individual, the smallest known for the species, represented by a complete skull and fragmentary skeleton. Although ~80% maximum size, it possesses a suite of characters associated with immaturity, and is regarded as a subadult. The ornamentation is characterized by a small, recurved, but fused nasal horncore; short, rounded postorbital horncores; and short, triangular, and flat parietal processes. Using this specimen, and additional skulls and bonebed material, the cranial ontogeny of Styracosaurus is described, and compared to Centrosaurus. In early ontogeny, the nasal horncores of Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus are thin, recurved, and unfused, but in the former the recurved morphology is retained into large adult size and the horncore never develops the procurved morphology common in Centrosaurus. The postorbital horncores of Styracosaurus are shorter and more rounded than those of Centrosaurus throughout ontogeny, and show great- er resorption later in ontogeny. -

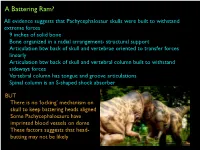

A Battering Ram?

A Battering Ram? All evidence suggests that Pachycephalosaur skulls were built to withstand extreme forces 9 inches of solid bone Bone organized in a radial arrangement- structural support Articulation btw back of skull and vertebrae oriented to transfer forces linearly Articulation btw back of skull and vertebral column built to withstand sideways forces Vertebral column has tongue and groove articulations Spinal column is an S-shaped shock absorber BUT There is no ‘locking’ mechanism on skull to keep battering heads aligned Some Pachycephalosaurs have imprinted blood vessels on dome These factors suggests that head- butting may not be likely Intraspecies Competition (typically male-male) Females are typically choosey Why? Because they have more to loose Common rule in biology: Females are expensive to lose, males are cheap (e.g. deer hunting) Females choose the male most likely to provide the most successful offspring Males compete with each other for access to female vs. female chooses the strongest male Choosey females // Strong males have more offspring => SEXUAL selection Many ways to do this... But: In general, maximize competition and minimize accidental deaths (= no fitness) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PontCXFgs0M http://www.metacafe.com/watch/1941236/giraffe_fight/ http://www.youtube.com/watch? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYDx1y38vGw http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULRtdk-3Yh4 Air-filled horn cores vs. solid bone skull caps... Gotta have a cheezy animated slide. Homalocephale Pachycephalosaurus Prenocephale Tylocephale Stegoceras Head butting Pachycephalosaurs Bone structure was probably strong enough to withstand collision Convex nature would favor glancing blows Instead, dome and spines seem better suited for “flank butting” So.. -

A New Maastrichtian Species of the Centrosaurine Ceratopsid Pachyrhinosaurus from the North Slope of Alaska

A new Maastrichtian species of the centrosaurine ceratopsid Pachyrhinosaurus from the North Slope of Alaska ANTHONY R. FIORILLO and RONALD S. TYKOSKI Fiorillo, A.R. and Tykoski, R.S. 2012. A new Maastrichtian species of the centrosaurine ceratopsid Pachyrhinosaurus from the North Slope of Alaska. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57 (3): 561–573. The Cretaceous rocks of the Prince Creek Formation contain the richest record of polar dinosaurs found anywhere in the world. Here we describe a new species of horned dinosaur, Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum that exhibits an apomorphic character in the frill, as well as a unique combination of other characters. Phylogenetic analysis of 16 taxa of ceratopsians failed to resolve relationships between P. perotorum and other Pachyrhinosaurus species (P. canadensis and P. lakustai). P. perotorum shares characters with each of the previously known species that are not present in the other, including very large nasal and supraorbital bosses that are nearly in contact and separated only by a narrow groove as in P. canadensis, and a rostral comb formed by the nasals and premaxillae as in P. lakustai. P. perotorum is the youngest centrosaurine known (70–69 Ma), and the locality that produced the taxon, the Kikak−Tegoseak Quarry, is close to the highest latitude for recovery of ceratopsid remains. Key words: Dinosauria, Centrosaurinae, Cretaceous, Prince Creek Formation, Kikak−Tegoseak Quarry, Arctic. Anthony R. Fiorillo [[email protected]] and Ronald S. Tykoski [[email protected]], Perot Museum of Nature and Science, 2201 N. Field Street, Dallas, TX 75202, USA. Received 4 April 2011, accepted 23 July 2011, available online 26 August 2011. -

Dinosaur Morphological Diversity and the End-Cretaceous Extinction

ARTICLE Received 24 Feb 2012 | Accepted 30 Mar 2012 | Published 1 May 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1815 Dinosaur morphological diversity and the end-Cretaceous extinction Stephen L. Brusatte1,2, Richard J. Butler3,4, Albert Prieto-Márquez4 & Mark A. Norell1 The extinction of non-avian dinosaurs 65 million years ago is a perpetual topic of fascination, and lasting debate has focused on whether dinosaur biodiversity was in decline before end- Cretaceous volcanism and bolide impact. Here we calculate the morphological disparity (anatomical variability) exhibited by seven major dinosaur subgroups during the latest Cretaceous, at both global and regional scales. Our results demonstrate both geographic and clade-specific heterogeneity. Large-bodied bulk-feeding herbivores (ceratopsids and hadrosauroids) and some North American taxa declined in disparity during the final two stages of the Cretaceous, whereas carnivorous dinosaurs, mid-sized herbivores, and some Asian taxa did not. Late Cretaceous dinosaur evolution, therefore, was complex: there was no universal biodiversity trend and the intensively studied North American record may reveal primarily local patterns. At least some dinosaur groups, however, did endure long-term declines in morphological variability before their extinction. 1 Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024 USA. 2 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University, New York, New York 10025 USA. 3 GeoBio-Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Richard- Wagner-Straße 10, Munich D-80333, Germany. 4 Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard-Wagner-Straße 10, Munich D- 80333, Germany. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S.L.B. -

Raptors in Action 1 Suggested Pre-Visit Activities

PROGRAM OVERVIEW TOPIC: Small theropods commonly known as “raptors.” THEME: Explore the adaptations that made raptors unique and successful, like claws, intelligence, vision, speed, and hollow bones. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION: Razor-sharp teeth and sickle-like claws are just a few of the characteristics that have made raptors famous. Working in groups, students will build a working model of a raptor leg and then bring it to life while competing in a relay race that simulates the hunting techniques of these carnivorous animals. AUDIENCE: Grades 3–6 CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS: Grade 3 Science: Building with a Variety of Materials Grade 3–6 Math: Patterns and Relations Grade 4 Science: Building Devices and Vehicles that Move Grade 6 Science: Evidence and Investigation PROGRAM ObJECTIVES: 1. Students will understand the adaptations that contributed to the success of small theropods. 2. Students will explore the function of the muscles used in vertebrate movement and the mechanics of how a raptor leg works. 3. Students will understand the function of the raptorial claw. 4. Students will discover connections between small theropod dinosaurs and birds. SUGGESTED PRE-VISIT ACTIVITIES UNDERstANDING CLADIstICS Animals and plants are often referred to as part of a family or group. For example, the dog is part of the canine family (along with wolves, coyotes, foxes, etc.). Scientists group living things together based on relationships to gain insight into where they came from. This helps us identify common ancestors of different organisms. This method of grouping is called “cladistics.” Cladistics is a system that uses branches like a family tree to show how organisms are related to one another.