A Revision of the Ceratopsia Or Horned Dinosaurs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Neoceratopsian Dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia And

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01222-7 OPEN A neoceratopsian dinosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia and the early evolution of ceratopsia ✉ Congyu Yu 1 , Albert Prieto-Marquez2, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig 3,4, Zorigt Badamkhatan4,5 & Mark Norell1 1234567890():,; Ceratopsia is a diverse dinosaur clade from the Middle Jurassic to Late Cretaceous with early diversification in East Asia. However, the phylogeny of basal ceratopsians remains unclear. Here we report a new basal neoceratopsian dinosaur Beg tse based on a partial skull from Baruunbayan, Ömnögovi aimag, Mongolia. Beg is diagnosed by a unique combination of primitive and derived characters including a primitively deep premaxilla with four pre- maxillary teeth, a trapezoidal antorbital fossa with a poorly delineated anterior margin, very short dentary with an expanded and shallow groove on lateral surface, the derived presence of a robust jugal having a foramen on its anteromedial surface, and five equally spaced tubercles on the lateral ridge of the surangular. This is to our knowledge the earliest known occurrence of basal neoceratopsian in Mongolia, where this group was previously only known from Late Cretaceous strata. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that it is sister to all other neoceratopsian dinosaurs. 1 Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York 10024, USA. 2 Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, ICTA-ICP, Edifici Z, c/de les Columnes s/n Campus de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès Sabadell, Barcelona, Spain. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA. 4 Institute of Paleontology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, ✉ Ulaanbaatar 15160, Mongolia. -

Six Adventure Road Trips

Easy Drives, Big Fun, and Planning Tips Six Adventure Road Trips DAY HIKES, FLY-FISHING, SKIING, HISTORIC SITES, AND MUCH MORE A custom guidebook in partnership with Montana Offi ce of Tourism and Business Development and Outside Magazine Montana Contents is the perfect place for road tripping. There are 3 Glacier Country miles and miles of open roads. The landscape is stunning and varied. And its towns are welcoming 6 Roaming the National Forests and alluring, with imaginative hotels, restaurants, and breweries operated by friendly locals. 8 Montana’s Mountain Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks are Biking Paradise the crown jewels, but the Big Sky state is filled with hundreds of equally awesome playgrounds 10 in which to mountain bike, trail run, hike, raft, Gateways to Yellowstone fish, horseback ride, and learn about the region’s rich history, dating back to the days of the 14 The Beauty of Little dinosaurs. And that’s just in summer. Come Bighorn Country winter, the state turns into a wonderland. The skiing and snowboarding are world-class, and the 16 Exploring Missouri state offers up everything from snowshoeing River Country and cross-country skiing to snowmobiling and hot springs. Among Montana’s star attractions 18 Montana on Tap are ten national forests, hundreds of streams, tons of state parks, and historic monuments like 20 Adventure Base Camps Little Bighorn Battlefield and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Whether it’s a family- 22 friendly hike or a peaceful river trip, there’s an Montana in Winter experience that will recharge your spirit around every corner in Montana. -

MEET the DINOSAURS! WHAT’S in a NAME? a LOT If You Are a Dinosaur!

MEET THE DINOSAURS! WHAT’S IN A NAME? A LOT if you are a dinosaur! I will call you Dyoplosaurus! Most dinosaurs get their names from the ancient Greek and Latin languages. And I will call you Mojoceratops! And sometimes they are named after a defining feature on their body. Their names are made up of word parts that describe the dinosaur. The name must be sent to a special group of people called the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to be approved! Did You The word DINOSAUR comes from the Greek word meaning terrible lizard and was first said by Know? Sir Richard Owen in 1841. © 2013 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® | 3 SEE IF YOU CAN FIND OUT THE MEANING OF SOME OF OUR DINOSAUR’S NAMES. Dinosaur names are not just tough to pronounce, they often have meaning. Dinosaur Name MEANING of Dinosaur Name Carnotaurus (KAR-no-TORE-us) Means “flesh-eating bull” Spinosaurus (SPY-nuh-SORE-us) Dyoplosaurus (die-o-pluh-SOR-us) Amargasaurus (ah-MAR-guh-SORE-us) Omeisaurus (Oh-MY-ee-SORE-us) Pachycephalosaurus (pak-ee-SEF-uh-low-SORE-us) Tuojiangosaurus (toh-HWANG-uh-SORE-us) Yangchuanosaurus (Yang-chew-ON-uh-SORE-us) Quetzalcoatlus (KWET-zal-coe-AT-lus) Ouranosaurus (ooh-RAN-uh-SORE-us) Parasaurolophus (PAIR-uh-so-ROL-uh-PHUS) Kosmoceratops (KOZ-mo-SARA-tops) Mojoceratops (moe-joe-SEH-rah-tops) Triceratops (try-SER-uh-TOPS) Tyrannosaurus rex (tuh-RAN-uh-SORE-us) Find the answers by visiting the Resource Library at Carnotaurus A: www.OmahaZoo.com/Education. Search word: Dinosaurs 4 | © 2013 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® DINO DEFENSE All animals in the wild have to protect themselves. -

The Transition from the Judith River Formation to the Bearpaw Shale

The transition from the Judith River Formation to the Bearpaw Shale (Campanian), north-central Montana by Roger Elmer Braun A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Earth Sciences Montana State University © Copyright by Roger Elmer Braun (1983) Abstract: The upper 15 m of the Judith River Formation on and adjacent to the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, north-central Montana is composed mostly of overbank mudrock, siltstone, fine-grained sandstone, and coal, with some cross-stratified channel sandstone in the lower part. The lower 15 m of the overlying Bearpaw Shale is a transgressive deposit composed primarily of concretionary silty shale with some clayey, silty sandstone zones and one bentonite bed. The source area for both formations was primarily in western Montana and Idaho, with the Elkhorn Mountains volcanics a major source of debris. The contact between the Judith River and Bearpaw formations is abrupt and lacks a transgressive sandstone facies. The transgression of the Bearpaw sea across the study area is considered to have been a nearly isochronous event because of the nature of the transition, small east-west differences in thickness between marker horizons, and similar elevations of the contact from east to west across undeformed parts of the study area. The Bearpaw transgression was caused mainly by tectonic thickening in the western Cordillera, which created subsidence primarily in the western and central portions of the Western Interior basin. The transgression was a nearly isochronous event that took place approximately 72 m.y. ago according to radiometric age dates on bentonite beds. -

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

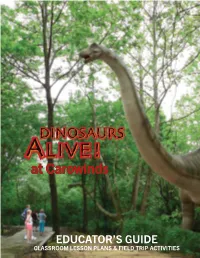

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Basal Ornithischia (Reptilia, Dinosauria)

A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE BASAL ORNITHISCHIA (REPTILIA, DINOSAURIA) Marc Richard Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2007 Committee: Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor Don C. Steinker Daniel M. Pavuk © 2007 Marc Richard Spencer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor The placement of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus and the Heterodontosauridae within the Ornithischia has been problematic. Historically, Lesothosaurus has been regarded as a basal ornithischian dinosaur, the sister taxon to the Genasauria. Recent phylogenetic analyses, however, have placed Lesothosaurus as a more derived ornithischian within the Genasauria. The Fabrosauridae, of which Lesothosaurus was considered a member, has never been phylogenetically corroborated and has been considered a paraphyletic assemblage. Prior to recent phylogenetic analyses, the problematic Heterodontosauridae was placed within the Ornithopoda as the sister taxon to the Euornithopoda. The heterodontosaurids have also been considered as the basal member of the Cerapoda (Ornithopoda + Marginocephalia), the sister taxon to the Marginocephalia, and as the sister taxon to the Genasauria. To reevaluate the placement of these taxa, along with other basal ornithischians and more derived subclades, a phylogenetic analysis of 19 taxonomic units, including two outgroup taxa, was performed. Analysis of 97 characters and their associated character states culled, modified, and/or rescored from published literature based on published descriptions, produced four most parsimonious trees. Consistency and retention indices were calculated and a bootstrap analysis was performed to determine the relative support for the resultant phylogeny. The Ornithischia was recovered with Pisanosaurus as its basalmost member. -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

Montana State Parks Guide Reservations for Camping and Other Accommodations: Toll Free: 1-855-922-6768 Stateparks.Mt.Gov

For more information about Montana State Parks: 406-444-3750 TDD: 406-444-1200 website: stateparks.mt.gov P.O. Box 200701 • Helena, MT 59620-0701 Montana State Parks Guide Reservations for camping and other accommodations: Toll Free: 1-855-922-6768 stateparks.mt.gov For general travel information: 1-800-VISIT-MT (1-800-847-4868) www.visitmt.com Join us on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram If you need emergency assistance, call 911. To report vandalism or other park violations, call 1-800-TIP-MONT (1-800-847-6668). Your call can be anonymous. You may be eligible for a reward. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks strives to ensure its programs, sites and facilities are accessible to all people, including those with disabilities. To learn more, or to request accommodations, call 406-444-3750. Cover photo by Jason Savage Photography Lewis and Clark portrait reproductions courtesy of Independence National Historic Park Library, Philadelphia, PA. This document was produced by Montana Fish Wildlife & Parks and was printed at state expense. Information on the cost of this publication can be obtained by contacting Montana State Parks. Printed on Recycled Paper © 2018 Montana State Parks MSP Brochure Cover 15.indd 1 7/13/2018 9:40:43 AM 1 Whitefish Lake 6 15 24 33 First Peoples Buffalo Jump* 42 Tongue River Reservoir Logan BeTableaverta ilof Hill Contents Lewis & Clark Caverns Les Mason* 7 16 25 34 43 Thompson Falls Fort3-9 Owen*Historical Sites 28. VisitorMadison Centers, Buff Camping,alo Ju mp* Giant Springs* Medicine Rocks Whitefish Lake 8 Fish Creek 17 Granite11-15 *Nature Parks 26DisabledMissouri Access Headw ibility aters 35 Ackley Lake 44 Pirogue Island* WATERTON-GLACIER INTERNATIONAL 2 Lone Pine* PEACE PARK9 Council Grove* 18 Lost Creek 27 Elkhorn* 36 Greycliff Prairie Dog Town* 45 Makoshika Y a WHITEFISH < 16-23 Water-based Recreation 29. -

Histology and Ontogeny of Pachyrhinosaurus Nasal Bosses By

Histology and Ontogeny of Pachyrhinosaurus Nasal Bosses by Elizabeth Kruk A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Systematics and Evolution Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Elizabeth Kruk, 2015 Abstract Pachyrhinosaurus is a peculiar ceratopsian known only from Upper Cretaceous strata of Alberta and the North Slope of Alaska. The genus consists of three described species Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai, and Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum that are distinguishable by cranial characteristics, including parietal horn shape and orientation, absence/presence of a rostral comb, median parietal bar horns, and profile of the nasal boss. A fourth species of Pachyrhinosaurus is described herein and placed into its phylogenetic context within Centrosaurinae. This new species forms a polytomy at the crown with Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis and Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum, with Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai falling basal to that polytomy. The diagnostic features of this new species are an apomorphic, laterally curved Process 3 horns and a thick longitudinal ridge separating the supraorbital bosses. Another focus is investigating the ontogeny of Pachyrhinosaurus nasal bosses in a histological context. Previously, little work has been done on cranial histology in ceratopsians, focusing instead on potential integumentary structures, the parietals of Triceratops, and how surface texture relates to underlying histological structures. An ontogenetic series is established for the nasal bosses of Pachyrhinosaurus at both relative (subadult versus adult) and fine scale (Stages 1-5). It was demonstrated that histology alone can indicate relative ontogenetic level, but not stages of a finer scale. Through Pachyrhinosaurus ontogeny the nasal boss undergoes increased vascularity and secondary remodeling with a reduction in osteocyte lacunar density. -

A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered from the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian)

The Journal of Paleontological Sciences: JPS.C.2019.01 1 TAKING COUNT: A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered From the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian). ______________________________________________________________________________________ Walter W. Stein- President, PaleoAdventures 1432 Mill St.. Belle Fourche, SD 57717. [email protected] 605-210-1275 ABSTRACT: A census of Hell Creek and Lance Formation dinosaur remains was conducted from April, 2017 through February of 2018. Online databases were reviewed and curators and collections managers interviewed in an effort to determine how much material had been collected over the past 130+ years of exploration. The results of this new census has led to numerous observations regarding the quantity, quality, and locations of the total collection, as well as ancillary data on the faunal diversity and density of Late Cretaceous dinosaur populations. By reviewing the available data, it was also possible to make general observations regarding the current state of certain exploration programs, the nature of collection bias present in those collections and the availability of today's online databases. A total of 653 distinct, associated and/or articulated remains (skulls and partial skeletons) were located. Ceratopsid skulls and partial skeletons (mostly identified as Triceratops) were the most numerous, tallying over 335+ specimens. Hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus) were second with at least 149 associated and/or articulated remains. Tyrannosaurids (Tyrannosaurus and Nanotyrannus) were third with a total of 71 associated and/or articulated specimens currently known to exist. Basal ornithopods (Thescelosaurus) were also well represented by at least 42 known associated and/or articulated remains. The remaining associated and/or articulated specimens, included pachycephalosaurids (18), ankylosaurids (6) nodosaurids (6), ornithomimids (13), oviraptorosaurids (9), dromaeosaurids (1) and troodontids (1). -

A Subadult Individual of Styracosaurus Albertensis

Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology 8:67–95 67 ISSN 2292-1389 A subadult individual of Styracosaurus albertensis (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) with comments on ontogeny and intraspecific variation inStyracosaurus and Centrosaurus Caleb M. Brown1,*, Robert B. Holmes2, Philip J. Currie2 1Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Box 7500, Drumheller, AB, T0J 0Y0, Canada; [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2E9, Canada; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: Styracosaurus albertensis is an iconic centrosaurine horned dinosaur from the Campanian of Alberta, Canada, known for its large spike-like parietal processes. Although described over 100 years ago, subsequent dis- coveries were rare until the last few decades, during which time several new skulls, skeletons, and bonebeds were found. Here we described an immature individual, the smallest known for the species, represented by a complete skull and fragmentary skeleton. Although ~80% maximum size, it possesses a suite of characters associated with immaturity, and is regarded as a subadult. The ornamentation is characterized by a small, recurved, but fused nasal horncore; short, rounded postorbital horncores; and short, triangular, and flat parietal processes. Using this specimen, and additional skulls and bonebed material, the cranial ontogeny of Styracosaurus is described, and compared to Centrosaurus. In early ontogeny, the nasal horncores of Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus are thin, recurved, and unfused, but in the former the recurved morphology is retained into large adult size and the horncore never develops the procurved morphology common in Centrosaurus. The postorbital horncores of Styracosaurus are shorter and more rounded than those of Centrosaurus throughout ontogeny, and show great- er resorption later in ontogeny.