South Africa's Exclusive Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The DHS Herald

The DHS Herald 23 February 2019 Durban High School Issue 07/2019 Head Master : Mr A D Pinheiro Our Busy School! It has been a busy week for a 50m pool, we have been asked School, with another one coming to host the gala here at DHS. up next week as we move from the summer sport fixtures to the This is an honour and we look winter sport fixtures. forward to welcoming the traditional boys’ schools in Durban This week our Grade 9 boys to our beautiful facility on attended their Outdoor Leadership Wednesday 27 February. The Gala excursion at Spirit of Adventure, starts at 4pm. Shongweni Dam. They had a great deal of fun, thoroughly enjoying Schools participating are: their adventure away from home, Contents participating in a wide range of Westville Boys’ High School activities. A full report will be in Kearsney College Our Busy School! 1 next week’s Herald. Clifton College Sport Results 2 Glenwood High School Weeks Ahead 3 The Chess boys left early Thursday Northwood School This Weekend’s Fixtures 3 morning for Bloemfontein to Durban High School participate in the Grey College MySchool 3 Chess Tournament. This is a The Gala is to be live-streamed by D&D Gala @ DHS 4 prestigious tournament, with 16 of DHS TV, so you can catch all the Rugby Fixtures 2019 4 our boys from Grades 10 to 12 action live if you are not able to competing against 22 schools from attend. Go to www.digitv.co.za to around the country. A full report sign up … it’s free! of their tour will also be found in next week’s Herald. -

Employment Equity Act: Public Register

STAATSKOERANT, 7 MAART 2014 No. 37426 3 CORRECTION NOTICE Extraordinary National Gazette No. 37405, Notice No. 146 of 7 March 2014 is hereby withdrawn and replaced with the following: Gazette No. 37426, Notice No. 168 of 7 March 2014. GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 168 OF 2014 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE EMPLOYMENT EQUITY ACT, 1998 (ACT NO. 55 OF 1998) I, Mildred Nelisiwe Oliphant, Minister of Labour, publish in the attached Schedule hereto the register maintained in terms of Section 41 of the Employment Equity Act, 1998 (Act No. 55 of 1998) of designated employers that have submitted employment equity reports in terms of Section 21, of the Employment Equity Act, Act No. 55 of 1998. 7X-4,i_L4- MN OLIPHANT MINISTER OF LABOUR vc/cgo7c/ t NOTICE 168 OF 2014 ISAZISO SASEREJISTRI SOLUNTU UMTHETHO WOKULUNGELELANISA INGQESHO, (UMTHETHO YINOMBOLO YAMA-55 KA-1998) Mna, Mildred Nelisiwe Oliphant, uMphathiswa wezabasebenzi, ndipapasha kule Shedyuli iqhakamshelwe apha irejista egcina ngokwemiqathango yeCandelo 41 lomThetho wokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, ka-1998 (umThetho oyiNombolo yama- 55 ka-1998)izikhundlazabaqeshi abangeniseiingxelozokuLungelelanisa iNgqeshongokwemigaqo yeCandelo 21, lomThethowokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka-1998. MN OLIPHANT UMPHATHISWA WEZEMISEBENZI oVe7,742c/g- This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 37426 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 7 MARCH 2014 List of designated employers who reported for the 01 September 2013 reporting cycle No: This represents sequential numbering of designated employers and bears no relation to an employer. (The list consists of 4984 large employers and 10182 small employers). Business name: This is the name of the designated employer who reported. Status code: 0 means no query. -

DSD II-Schulen

Sekretariat der Kultusministerkonferenz Liste der ausländischen Sekundarschulen mit Möglichkeit zum Erwerb des DSD II Land Schulort Schule Aegypten Alexandria Future Language School Alexandria El Gouna El Gouna International School, El Gouna Kairo Deutsche Evangelische Oberschule Kairo Kairo Deutsche Schule Beverly Hills, Kairo Kairo Deutsche Schule Heliopolis, Europa-Schule Kairo Albanien Elbasan Fremdsprachenmittelschule "Mahmut dhe Ali Cungu", Elbasan Shkoder Fremdsprachenmittelschule Sheijnaze Juka, Shkoder Tirana Fremdsprachenmittelschule "Asim Vokshi", Tirana Argentinien Bariloche Deutsche Schule Bariloche Buenos Aires Deutsche Schule Villa Ballester Buenos Aires Gartenstadt-Schule El Palomar, Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Goethe-Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Hölters-Schule Villa Ballester Buenos Aires Humboldt-Sprachakademie an der Goethe-Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Pestalozzi-Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Schiller Schule Buenos Aires Cordoba Deutsche Schule Cordoba Eldorado Hindenburg-Schule Eldorado Florida Rudolf-Steiner-Schule Florida Hurlingham Deutsche Schule Hurlingham Lanus Oeste Deutsche Schule Lanus Oeste Mar del Plata Johann Gutenberg Schule Montecarlo Deutsche Schule Montecarlo Quilmes Deutsche Schule Quilmes Rosario Goethe-Schule Rosario Temperley Deutsche Schule Temperley Villa General Belgrano Deutsche Schule Villa General Belgrano Armenien Eriwan Mesrop-Maschtoz Schule, Eriwan Eriwan Mittelschule Nr. 5 Eriwan Eriwan Mittelschule Nr. 6 Hakob Karapentsi Bolivien Cochabamba Colegio Fröbel Cochabamba La Paz Deutsche Schule La Paz Oruro Colegio Aleman Oruro Santa Cruz de Bolivia Deutsche Schule Santa Cruz de Bolivia Bosnien-Herzegowina Banja Luka Gymnasium Banja Luka Mostar Gymnasium Mostar Sarajewo 2. Gymnasium Sarajewo Sarajewo 3. Gymnasium Sarajewo Seite 1 von 14 Stand: 06.05.2008 Sekretariat der Kultusministerkonferenz Liste der ausländischen Sekundarschulen mit Möglichkeit zum Erwerb des DSD II Land Schulort Schule Sarajewo 4. -

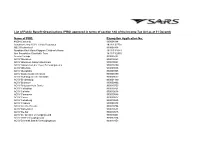

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

We Disappear Ariane Louise Sandford Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 We disappear Ariane Louise Sandford Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sandford, Ariane Louise, "We disappear" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14551. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14551 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. We disappear by Ariane Louise Sandford A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Program of Study Committee: Mary Swander, Major Professor Jon Billman Amy Slagell Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Ariane Louise Sandford, 2007. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 1443084 Copyright 2007 by Sandford, Ariane Louise All rights reserved. UMI Microform 1443084 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ii -

Report on the National Senior Certificate Examination Results 2010

EDUCATIONAL MEASUREMENT, ASSESSMENT AND PUBLIC EXAMINATIONS REPORT ON THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION RESULTS 2010 REPORT ON THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION RESULTS • 2010 His Excellency JG Zuma the President of the Republic of South Africa “On the playing field of life there is nothing more important than the quality of education. We urge all nations of the world to mobilise in every corner to ensure that every child is in school” President JG Zuma 1 EDUCATIONAL MEASUREMENT, ASSESSMENT AND PUBLIC EXAMINATIONS The Minister of Basic Education, Mrs Angie Motshekga, MP recently opened the library at the Inkwenkwezi Secondary School in Du Noon on 26 October 2010 and encouraged learners to read widely and this will contribute to improving their learning achievement. The Minister of Basic Education, Mrs Angie Motshekga, MP has repeatedly made the clarion call that “we owe it to the learners, the country and our people to improve Grade 12 results as committed”. 2 REPORT ON THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION RESULTS • 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD BY MINISTER . 7 1. INTRODUCTION . 9 2. THE 2010 NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE (NSC) EXAMINATION . 10 2.1 The magnitude and size of the National Senior Certificate examination . 10 2.2 The examination cycle . 11 2.3 Question Papers . 15 2.4 Printing, packing and distribution of question papers . 18. 2.5 Security . 19 2.6 The conduct of the 2010 National Senior Certificate (NSC) . 19 2.7 Processing of marks and results on the Integrated Examination Computer System (IECS) . 20 2.8 Standardisation of the NSC Results . 21 2.9 Viewing, remarking and rechecking of results during the appeal processes . -

011 – OBITUARY for DENIS EMERY

South African National Society History - Culture and Conservation. Join SANS. Founded in 1905 for the preservation of objects of Historical Interest and Natural Beauty http://sanationalsociety.co.za/ PO Box 47688, Greyville, 4023, South Africa Email: [email protected] | Tel: 071 746 1007 NEWS BRIEF OBITUARY DENIS EMERY SLANEY – 14 NOVEMBER 1929 TO 11 FEBRUARY 2015 Denis Slaney was born in Durban and grew up in Overport near Overport House and McCord’s Hospital. He was educated at Durban High School and studied at the University of Natal [Pietermaritzburg]. He trained to be a teacher and on leaving university taught for one term at Port Shepstone High School before being posted to Estcourt High School where he taught history and geography for the next twenty years. He in fact taught, or as he liked to put it “tried to teach” his future wife, Dawn Hope, for four years. Twenty years later they married in1971. Shortly afterwards Denis was promoted as Vice Principal and Head of History at Northlands Boys’ High School and they moved to Durban. He and Dawn lived at Westville where soon after their arrival their son Kevin was born. They lived there for the next forty-two years. Although Denis was a strict disciplinarian, he won the respect of his pupils as a result of his fairness and the ability to pass on his knowledge. Dawn and Kevin were touched by the number of past pupils who contacted them and remembered Denis with affection. From Northlands Denis was promoted to Head Master of Brettonwood High School and finally Head Master of George Campbell High School. -

Chronicle for 1955

r- -J-SM: KEARSNEY j. COLLEGE CHRONICLE O#?PE o\t^ ■im July, 1955 '. "sy KEARSNEY COLLEGE CHRONICLE WPE D\^ July, 1955 m m M ipt m A / m 8® © w SCHOOL LAYOUT, INCLUDING PEMBROKE HOUSE. Kearsney College Chronicle Vol. 4, No. I July, 1955 ON SCHOOL MAGAZINES I think It will be generally agreed that, except for those most intimately concerned, School Magazines would not be classified among the "best sellers". They contain none of the features which attract the common herd, not even a bathing beauty on the cover (though it's an idea). Their interest-value is very local; to the outsider, the lists of event-winners or prize-winners have the monotony of a telephone directory, and does it really matter whether we won the match or lost it? Only to those most closely concerned does it matter. What, Magazine Reader, do you look for? Let's be honest. Yes, of course. You turn over hastily to those places where your own name is likely to appear: your own name, gold-embroidered, standing there for everyone to see, if it were not for the fact that they are too busy looking for their own names. That done, what else is there of interest? Well—you already knew the results of the matches, so that is not news; the activities of your Society are known to you and of no interest to anyone else; the Old Boys' News is just a catalogue of unknown names; articles are boring, except for the writers. Yes, surely this is not a best-seller. -

Press Release Arcadia, Pretoria 0083 South Africa 9 September, 2013 TEL +27 (0)12 427 8936 Page 1 of 3 FAX +27 (0)12 343 3606

ADDRESS 180 Blackwood Street Press Release Arcadia, Pretoria 0083 South Africa 9 September, 2013 TEL +27 (0)12 427 8936 Page 1 of 3 FAX +27 (0)12 343 3606 [email protected] German Weeks 2013: www.southafrica.diplo.de Meet Germany in South Africa today! www.gicafrica.diplo.de www.germanweeks2013.co.za Germany: a founding member of the EU. Europe’s strongest economy. A vibrant society. A strategic partner of South Africa. A land of ideas and innovation. What else would you like to know about today’s Germany and the strength and depth of South African-German relations? You are cordially invited to learn more. In order to present today’s Germany to a wider South African audience, the German Embassy, the Southern African – German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SAGCC), as well as various German institutions and companies in South Africa present the German Weeks 2013. Comprising of 25 dynamic and engaging events, the German Weeks will take place from 12 September to the end of October, 2013. The weeks ahead With the official slogan “Meet Germany in South Africa today”, the German Weeks 2013 showcase an authentic and multi-faceted image of modern German society through various lenses such as lifestyle, politics, business and technology, primarily in Johannesburg and Pretoria. Furthermore, they introduce and highlight Germany’s presence within South Africa to new audiences. Highlights The German Weeks 2013 programme main highlights include the opening event at the Deutsche Schule Pretoria’s Oktoberfest (12 September), a German election party at the Goethe-Institut (22 September), a “science slam” in cooperation with the DST and Sci-Bono (9 October), and, finally, the closing event at the SAGCC/ Deutsche Internationale Schule Johannesburg Innovation and Job Fair (19 October). -

Durban Preparatory High School 2014 Yearbook

DPHS EDUCATIONAL TRUST Millennium Foundation Members Richard Neave; Hank & Trish Pike; Mike & Jann Nichol; Rob & Silvia Havemann; Jean & Sue Robert; Craig & Roly Ewin; Jim & Inri McManus; Andrew & Iain Campbell; Neeran & Sabina Besesar; AK & Khadija Kharsany; Peter & Kathy McMaster; Anthony & Mandy Morgan; Debbie Mathew; Tony Savage; Colin & Liz Woodcock; Richard & Birgit Eaton; Peter & Belinda Croxon; Derek & Andrea Field; Ian & Marian Pace; Marc & Damian Tsouris; Michael Hobson; Marc Rayson; Matthew & Luke Lasich; Deon & Jody Le Noury; Mikhael & Danyal Vawda; Hugh & Bridget Bland; John & Evan Nolte; Mark & Gary Smith; Albert & Sean Burger; Guy & Merril Bowman; Brett Cubitt; Ryan & Lyle Matthysen; Daniel & Matthew Murphy; Daniel & Jason Airey; Jonathan & Christopher Brown; Clinton Scott; Barry Wilson; Gareth & Sean May; Mohammed & Imran Fakroodeen; Dax & Scott Campbell; Gareth Walsh; Matthew Everitt; Kai Petty; Ian & Jeanine Topping; David & Cecilia Hey; Annette & Byron Briscoe; James,Matthew & David Gilmour; Luke & Warrick Shannon; Nicholas Coppin; Simon & Daniel Atlas; Jason & Ryan Pender; Rory West; Craig de Villiers; Justin & Bradley Ball; Murray & Andrew Taylor; Warren Nell; Robert & Andrew Harrison; Fareeda & Ziyaad Aboobaker; Ant & Romaine Chaplin; Matthew Sargent; Tom & Scott Brown; Gareth van den Bergh; Mark Hunter; Grant & Ryan Dinkele; Rob & Lynn Farrar; Michael, Diana & Andrew Mackintosh; John Mamet; Keaton Heycocks; Dane Thompson; Nicholas, Jamie & Mark van der Riet; Jaryd & Joshua Bouwer; Stuart Hargreaves; John Dand; Thomas -

Ieb Outstanding & Commendable Achievements Nsc 201211Nsc

IEB OUTSTANDING & COMMENDABLE ACHIEVEMENTS NSC 201211NSC Outstanding Achievement 121017020059 CALDEIRA; MARCO CBC ST AQUINAS; BOKSBURG 121023020444 KEW-SIMPSON; SARAH JESSICA CORNWALL HILL COLLEGE 121024020288 VOIGTS; NINKE ANNELI CRESTON COLLEGE 121027020247 ECIM; DUŠAN DE LA SALLE HOLY CROSS COLLEGE; VICTORY PARK 121027020611 PARSCHAU; CHRISTIAN GEORG DE LA SALLE HOLY CROSS COLLEGE; VICTORY PARK 121028020232 VON SEYDLITZ; MICHAEL DEUTSCHE SCHULE; HERMANNSBURG 121033020318 LOWE; JUSTINE KATHERINE DIOCESAN SCHOOL FOR GIRLS; GRAHAMSTOWN 121033020437 REPAPIS; EDEN-EVE DIOCESAN SCHOOL FOR GIRLS; GRAHAMSTOWN 121037020327 KHAN; SALMA DURBAN GIRLS` COLLEGE 121037020804 VALJEE; MISHKA AJIT DURBAN GIRLS` COLLEGE 121047020124 GERINGER; IZELLE FELIXTON COLLEGE 121049020323 MUNRO; TIAAN GLENWOOD HOUSE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL 121057020447 WESSELS; CAREL HATFIELD CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 121058020467 HARRIS; TINEKE WILMA HELPMEKAAR KOLLEGE 121058020640 KRUGER; ANNA-MART HELPMEKAAR KOLLEGE 121058020759 LOTRIET; REYNARD MALCOLM HELPMEKAAR KOLLEGE 121058020877 NEETHLING; REZANNE HELPMEKAAR KOLLEGE 121065020667 STEYN; EMILY-ROSE SIMOES HOLY ROSARY SCHOOL 121068020436 HOLTES; RYAN DAVID KEARSNEY COLLEGE 121068020484 JORDAAN; WALTER JACOBUS KEARSNEY COLLEGE 121068020528 KIRSTEN; CRAIG MICHAEL KEARSNEY COLLEGE 121068020626 LUTCHMAN; MANDHIR KEARSNEY COLLEGE 121068020866 PEARS; TRAVIS ASHCRAFT KEARSNEY COLLEGE 121068021013 SPARKS; NATHAN BARRY KEARSNEY COLLEGE 121069020422 FAVISH; ASHLEIGH KING DAVID HIGH SCHOOL; LINKSFIELD 121069020691 JACOBSON; RYAN JONATHAN KING DAVID -

Verzeichnis Der Schulen, an Denen Das Deutsche Sprachdiplom Der Kultusministerkonferenz - Stufe II - Angeboten Wird

Verzeichnis der Schulen, an denen das Deutsche Sprachdiplom der Kultusministerkonferenz - Stufe II - angeboten wird. Ägypten DS Beverly Hills Kairo Ägypten El Gouna International School El Gouna Ägypten Europa-Schule Kairo Kairo Albanien Fremdsprachenmittelschule "Asim Vokshi" Tirana Albanien Fremdsprachenmittelschule "Mahmut dhe Ali Cungu", Elbasan Elbasan Albanien Fremdsprachenmittelschule Sheijnaze Juka, Shkoder Shkodra Albanien Sami Frasheri Gymnasium Tirana Argentinien Deutsche Schule Bariloche Bariloche Argentinien Deutsche Schule Cordoba Cordoba Argentinien Deutsche Schule Hurlingham Hurlingham Argentinien Deutsche Schule Lanus Oeste Lanus Oeste Argentinien Deutsche Schule Montecarlo Montecarlo Argentinien Deutsche Schule Quilmes Quilmes Argentinien Deutsche Schule Temperley Temperley Argentinien Deutsche Schule Villa Ballester Villa Ballester Argentinien Deutsche Schule Villa General Belgrano Villa General Belgrano Argentinien Gartenstadt-Schule El Palomar, Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Argentinien Goethe-Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Argentinien Goethe-Schule Rosario Rosario Argentinien Hindenburg-Schule Eldorado Eldorado Argentinien Hölters-Schule Villa Ballester Villa Ballester Argentinien Humboldt-Sprachakademie an der Goethe-Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Argentinien Johann Gutenberg Schule Mar del Plata Argentinien Pestalozzi-Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Stand: 01.04.2014 Die Anschriften und weitere Daten zu diesen Schulen können Sie hier abrufen: http://weltkarte.pasch-net. Seite 1 von 31 Verzeichnis der Schulen, an denen das Deutsche Sprachdiplom der Kultusministerkonferenz - Stufe II - angeboten wird. Argentinien Rudolf-Steiner-Schule Florida Florida Argentinien Schiller Schule Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Armenien B. Jamkotshyan Oberschule / 119. Schule Eriwan Armenien Mesrop Maschtoz Privatschule Eriwan Armenien Mittelschule Nr. 5 Eriwan Eriwan Armenien Mittelschule Nr. 6 Eriwan Belarus 24. Schule (Gymnasium College) Minsk Minsk Belarus 73. Schule Minsk Minsk Belarus Gymnasium Nr. 2 Pinsk Pinsk Belarus Mittelschule Nr.