The Effects of Atlanta's Urban Regime Politics On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

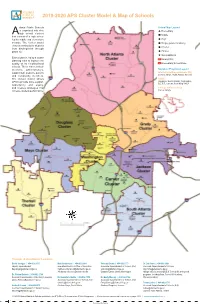

2019-2020 APS Cluster Model & Map of Schools

2019-2020 APS Cluster Model & Map of Schools tlAntA Public Schools School Map Legend is organized into nine Elementary high school clusters A Middle that consist of a high school fed by middle and elementary High schools. The cluster model Single-gender Academy ensures continuity for students Charter from kindergarten through grade 12. Partner Non-traditional EAch cluster is led by A cluster Emory/CDC planning team to improve the quality of its neighborhood Elementary School Zone schools. These teams include teachers, administrators, Signature Programs Legend support staff, students, parents International Baccalaureate (IB) and community members. Jackson, Mays, North Atlanta, Therrell The cluster model Allows STEM APS to provide more support, Douglass, South Atlanta, Washington, B.E.S.T., Coretta Scott King YWLA opportunity and equity, and creates strategies that College & Career Prep increase student performance. Carver, Grady Cluster & Academic Leaders David Jernigan | 404-802-2875 Matt Underwood | 404-802-2864 Yolonda Brown | 404-802-2777 Dr. Dan Sims | 404-802-2693 Deputy Superintendent Executive Director of Offce of Innovation Associate Superintendent of Schools (K-8) Associate Superintendent of Schools [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] All charter schools & partner schools Clusters: Carver, Grady, Washington All high schools, including B.E.S.T. and CSK, and special Dr. Olivine Roberts | 404-802-2790 programs, including Crim, Forrest Hill Academy, Assistant Superintendent of Teaching & Learning Dr. Danielle S. Battle | 404-802-7550 Dr. Emily Massey | 404-802-3742 Phoenix Academy [email protected] Associate Superintendent of Schools (K-8) Associate Superintendent of Schools (K-8) [email protected] [email protected] Tommy Usher | 404-802-2776 Katika D. -

James.Qxp March Apri

COBB COUNTY A BUSTLING MARCH/APRIL 2017 PAGE 26 AN INSIDE VIEW INTO GEORGIA’S NEWS, POLITICS & CULTURE THE 2017 MOST INFLUENTIAL GEORGIA LOTTERY CORP. CEO ISSUE DEBBIE ALFORD COLUMNS BY KADE CULLEFER KAREN BREMER MAC McGREW CINDY MORLEY GARY REESE DANA RICKMAN LARRY WALKER The hallmark of the GWCCA Campus is CONNEE CTIVITY DEPARTMENTS Publisher’s Message 4 Floating Boats 6 FEATURES James’ 2017 Most Influential 8 JAMES 18 Saluting the James 2016 “Influentials” P.O. BOX 724787 ATLANTA, GEORGIA 31139 24 678 • 460 • 5410 Georgian of the Year, Debbie Alford Building A Proposed Contiguous Exhibition Facilityc Development on the Rise in Cobb County 26 PUBLISHED BY by Cindy Morley INTERNET NEWS AGENCY LLC 2017 Legislators of the Year 29 Building B CHAIRMAN MATTHEW TOWERY COLUMNS CEO & PUBLISHER PHIL KENT Future Conventtion Hotel [email protected] Language Matters: Building C How We Talk About Georgia Schools 21 CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER LOUIE HUNTER by Dr. Dana Rickman ASSOCIATE EDITOR GARY REESE ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES Georgia’s Legal Environment on a PATTI PEACH [email protected] Consistent Downward Trend 23 by Kade Cullefer The connections between Georggia World Congress Center venues, the hotel MARKETING DIRECTOR MELANIE DOBBINS district, and the world’world s busiest aairporirport are key differentiaferentiatorsators in Atlanta’Atlanta’s ability to [email protected] Georgia Restaurants Deliver compete for in-demand conventions and tradeshows. CIRCULATION PATRICK HICKEY [email protected] Significant Economic Impact 31 by Karen Bremer CONTRIBUTING WRITERS A fixed gateway between the exhibit halls in Buildings B & C would solidify KADE CULLEFER 33 Atlanta’s place as the world’s premier convention destination. -

Metro Atlanta Cultural Assessment FINAL REPORT

metro atlanta cultural assessment FINAL REPORT table of contents acknowledgements. .3 executive summary. .4 cultural inventory cultural inventory summary. .8 creative industries revenue & compensation. 10 creative industries businesses & employment. 12 nonprofit cultural organizations. 27 cultural facilities. .40 where audiences originate. 53 cultural plans, programs, policies & ordinances cultural plans, programs & policies overview. 58 cultural affairs departments, plans, ordinances & policies. .59 regional planning agencies with cultural components. 63 regional cultural agencies. .65 examples of cultural plans. .67 cultural planning funding sources. .70 cultural forums cultural forums overview. 72 key findings, issues & opportunities. 73 all findings. 87 minutes Cherokee. 84 Clayton. 87 Cobb. 93 DeKalb. .98 Douglas. 105 North Fulton. 112 South Fulton. 120 Gwinnett. .127 Henry. .135 Rockdale. .142 City of Atlanta. 148 external appendices appendix A: cultural industries revenue and compensation technical codes appendix B: cultural industries employment and businesses technical codes appendix C: nonprofit cultural organizations technical codes appendix D: list of nonprofit cultural organizations by county appendix E: list of cultural facilities by county 2 | METRO ATLANTA CULTURAL ASSESSMENT FINAL REPORT acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the strong support of the Boards of Directors of both the Atlanta Regional Commission and the Metro Atlanta Arts and Culture Coalition. Atlanta Regional Commission Board Members Tad Leithead (ARC Chair), Buzz Ahrens, W. Kerry Armstrong, Julie K. Arnold, Eldrin Bell, Kip Berry, C. J. Bland, Mike Bodker, Dennis W. Burnette, John Eaves, Burrell Ellis, Todd E. Ernst, Bill Floyd, Herbert Frady, Rob Garcia, Gene Hatfield, Bucky Johnson, Doris Ann Jones, Tim Lee, Liane Levetan, Lorene Lindsey, Mark Mathews, Elizabeth “BJ” Mathis, Randy Mills, Eddie L. -

First and Second Generations of Urban Black Mayors: Atlanta, Detroit, and St

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-2001 First and Second Generations of Urban Black Mayors: Atlanta, Detroit, and St. Louis Harold Eugene Core Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Core, Harold Eugene, "First and Second Generations of Urban Black Mayors: Atlanta, Detroit, and St. Louis" (2001). Master's Theses. 3883. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3883 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIRST AND SECOND GENERATIONS OF URBAN BLACK MAYORS: ATLANTA, DETROIT, AND ST. LOUIS by Harold Eugene Core, Jr A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College In partial fulfillmentof the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2001 © 2001 Harold Eugene Core, Jr ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to first acknowledge the courage and leadership of those very first urban black mayors. Without their bravery, hard work, and accomplishments this research, and possibly even this researcher would not exist. In many ways they served as the flagship for the validity of black political empowerment as they struggled to balance their roles as leaders of large cities and spokespersons for the African American cause. Secondly I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee, specifically Dr. -

DOUGLASS SELBY Hunton & Williams

METRO ATLANTA EDITION | VOLUME 3 ISSUE 4 www.AttorneyAtLawMagazine.com MAGAZINE® DOUGLASS SELBY Hunton & Williams LLP Practice Group Profile A-LIST ATLANTA LAWYERS EDITION PRACTICE GROUP PROFILE DOUGLASS SELBY HUNTON & WILLIAMS LLP Building a Legacy in Atlanta By Laura Maurice ublic finance makes possible much of the infrastructure are on the leading edge of the region’s most sophisticated new and capital improvements on which a vibrant and developments in finance law. growing city like Atlanta depends. When it comes “Public finance has traditionally been a strong practice, both to public finance law in town, Douglass Selby and for the firm and the Atlanta office,” says Kurt Powell, managing Pthe attorneys at Hunton & Williams LLP are often behind partner of Hunton’s Atlanta office. “We are very fortunate to the scenes of some of the city’s most notable deals, whether have Doug as a leader and are confident that the practice will it’s Philips Arena, the Atlanta Beltline or the International continue to flourish under his guidance.” Terminal at Hartsfield International Airport. As bond counsel Public finance encompasses a combination of specialties for the busiest airport in the world and the recipient of – tax law, securities and disclosure law, and state law – all multiple Bond Deals of the Year, Selby and the team at Hunton of which are required to finance the activities of entities or Bill Adler Photography Matthew Calvert, Douglass Selby, Caryl Greenberg Smith & Kurt Powell projects borrowing in the tax-exempt capital markets. Selby’s experience includes advising, negotiating and documenting tax-exempt bond transactions for airports, stadiums, water and sewer systems, other governmental facilities and infrastructure, public-private partnerships (P3s) through TIF/ TAD, PILOT and Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) district-backed financings and providing general corporate Bill Adler Photography advice to governmental authorities. -

Atlanta's Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class

“To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 by William Seth LaShier B.A. in History, May 2009, St. Mary’s College of Maryland A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Eric Arnesen James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that William Seth LaShier has passed the Final Examinations for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 20, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 William Seth LaShier Dissertation Research Committee Eric Arnesen, James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History, Dissertation Director Erin Chapman, Associate Professor of History and of Women’s Studies, Committee Member Gordon Mantler, Associate Professor of Writing and of History, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed this dissertation without the generous support of teachers, colleagues, archivists, friends, and most importantly family. I want to thank The George Washington University for funding that supported my studies, research, and writing. I gratefully benefited from external research funding from the Southern Labor Archives at Georgia State University and the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Library (MARBL) at Emory University. -

Public Broadcasting Atlanta (PBA) Atlanta, GA

LEADERSHIP PROFILE President and Chief Executive Officer Public Broadcasting Atlanta (PBA) Atlanta, GA We inspire a community of life-long learners. --PBA Mission THE OPPORTUNITY Public Broadcasting Atlanta (PBA) is a trusted epicenter of news, culture and storytelling in Atlanta, the 10th largest U.S. media market. PBA reaches 1.4 million viewers and listeners a month via WABE, the dominant NPR station, ATL PBA TV, a full-service PBS station, and award-winning podcasts and other compelling digital and educational offerings. PBA is integral to the metro Atlanta community. Most of its $14.7 million budget is funded by local donors and underwriters. In the past five years, WABE has doubled its news team, resulting in near-daily story pickup by NPR. PBA has exponentially grown its younger and more diverse audiences. This is a time of promise at PBA. The organization has transformed itself with world-class talent and storytelling that is platform-agnostic. It has a culture of boldness and innovation. At a moment of epic global challenges and intense media competition, PBA is poised to leverage reporting and storytelling, deepen relationships with current and emerging audiences, focus on increasing donor support and revenues, and capitalize on its local and national profile. The new CEO will have the exciting mandate to lead PBA into its next era. PBA has built a world-class team that collaborates across platforms and has amplified and diversified its audiences and offerings. The organization has an elevated profile. PBA’s mission, vision and plan are a clarion call to ongoing transformation, extraordinary content and financial growth. -

Class of 2015 Will Be Remembered for 'Bold Humility'

Commencement SPECIAL ISSUE Online at news.emory.edu MAY 11, 2015 MEMORIES & TIPS FOR NEW Cuttino Award winner Jensen 4 MILESTONES EMORY ALUMNI Take a look back Learn how to stay Jefferson Award winner Patterson 5 at some of the key connected to your Scholar/Teacher Award winner Long 5 moments shared by class and the university the Class of 2015. after Commencement. Honorary degree recipients 12 Pages 6–7 Page 11 Commencement by the numbers 12 Class of 2015 will be remembered for ‘bold humility’ Emory Photo/Video Emory’s 170th Commencement celebrates the diverse achievements of the Class of 2015, from academic excellence to compassionate community service. BY KIMBER WILLIAMS This year’s ceremony coincides with the celebration of “100 Years boldness, or bold humility,” demonstrating “a willingness to work in Atlanta,” an observance kicked off in February honoring Emory’s boldly toward noble ideals — social justice, support of refugee As the Class of 2015 gathers to celebrate Emory University’s 170th charter to establish an Atlanta campus in 1915. communities, public health and mental health in Africa and Latin Commencement ceremony, the colorful pomp and pageantry will un- As a result, this year’s graduates represent a class that is in many America, access to education for undocumented residents of our fold amid a series of significant milestones, for both graduates and ways “distinguished by paradox,” says Emory President James Wagner. country, peaceful resolution in the Middle East.” the university. “For one thing, it has the unique distinction of entering during At the same time, “these students have demonstrated real humility Rooted in centuries-old tradition, graduation exercises will the fall semester when Emory celebrated its 175th anniversary, and in the way they extend forgiveness and compassion to those who falter begin Monday, May 11, at 8 a.m., as the plaintive cry of bagpipes graduating as Emory is celebrating its 100th anniversary,” Wagner in our shared work,” Wagner says. -

Atlanta Public Schools' School Closure, Consolidation and Partnerships Plan in Alignment with the District Transformation Stra

Atlanta Public Schools’ School Closure, Consolidation and Partnerships Plan in Alignment with the District Transformation Strategy For Board Consideration – March 6, 2017 Executive Summary The Atlanta Public Schools (APS) School Closure, Consolidation and Partnerships Plan in Alignment with the District Transformation Strategy is presented for the consideration of the Board after an extensive communication and public engagement process. The plan was developed to further the district’s Transformation effort, address the under-utilization of schools and launch strategic partnerships over key district priorities. School Closures and Consolidations School closures or consolidations were considered where there were schools with inadequate performance, low enrollment relative to the capacity of the building, facilities in need of significant investment, and the performance of neighboring schools. The following closures and consolidations are recommended: Jackson Cluster – At the start of School Year 2017-2018, close Whitefoord Elementary School, redistricting students to Toomer Elementary and Burgess-Peterson Academy. Redistrict a portion of Parkside Elementary School students to Benteen Elementary School. Mays Cluster – At the start of School Year 2017-2018, close Adamsville Primary, restructuring Miles Intermediate as a PreK-5 school and redistricting some Adamsville and Miles students to West Manor Elementary. Douglass Cluster – At the start of School Year 2017-2018, relocate the Business, Engineering, Science and Technology Academy at the Benjamin S. Carson Educational Complex (BEST) to the Coretta Scott King Young Women’s Leadership Academy (CSK) with two 6-12 single gender academies on the CSK campus. Beginning with School Year 2017-2018, phase out the closure of Harper-Archer Middle School by serving only 7th and 8th grade at Harper-Archer. -

GMA Officers Savannah International Trade and Convention Center

GOLD SPONSORS: PRESENTING SPONSOR: SILVER SPONSORS: PLATINUM SPONSORS: BRONZE SPONSORS: Make SPINE to fit text pages GMA Officers Savannah International Trade and Convention Center WUpperelcome Levelto the Georgia Municipal Associa- tion’s 85th Annual Convention! It is always good to gather with the GMA “family” of cities in Savannah and use the opportunity to grow professionally, learn from our interactions with each other and plan together to meet the needs of our cities. This year, the theme of our convention is “The Character of Cities: Civility, Kindness, Inclusion.” President 1st Vice Throughout the Convention, we’ll be learning what Dorothy Hubbard President others are doing to be inclusive and encourage civili- Mayor, Albany Linda Blechinger ty. We’ll explore what defines city “character” – such Mayor, Auburn as its people, amenities, attitude or other attributes. Cities really are where democracy shines, and our Annual Convention embodies the spirit of the Convention theme. We come together from all over the state with different backgrounds, political views and experiences. But despite those differences, city leaders are excited to reconnect with each other and share ideas and support each other in our passion for public service. It really is inspiring to see city officials working together to solve the challenges our communities face and to find ways to improve the 2nd Vice 3rd Vice quality of life in our cities and our state. Hopefully, President President you will return to your city refreshed and inspired! Phil Best Vince Williams I encourage you to make the most of your Mayor, Dublin Mayor, Union City Convention experience. -

Izfs4uwufiepfcgbigqm.Pdf

PANTHERS 2018 SCHEDULE PRESEASON Thursday, Aug. 9 • 7:00 pm Friday, Aug. 24 • 7:30 pm (Panthers TV) (Panthers TV) GAME 1 at BUFFALO BILLS GAME 3 vs NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS Friday, Aug. 17 • 7:30 pm Thursday, Aug. 30 • 7:30 pm (Panthers TV) (Panthers TV) & COACHES GAME 2 vs MIAMI DOLPHINS GAME 4 at PITTSBURGH STEELERS ADMINISTRATION VETERANS REGULAR SEASON Sunday, Sept. 9 • 4:25 pm (FOX) Thursday, Nov. 8 • 8:20 pm (FOX/NFLN) WEEK 1 vs DALLAS COWBOYS at PITTSBURGH STEELERS WEEK 10 ROOKIES Sunday, Sept. 16 • 1:00 pm (FOX) Sunday, Nov. 18 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 2 at ATLANTA FALCONS at DETROIT LIONS WEEK 11 Sunday, Sept. 23 • 1:00 pm (CBS) Sunday, Nov. 25 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 3 vs CINCINNATI BENGALS vs SEATTLE SEAHAWKS WEEK 12 2017 IN REVIEW Sunday, Sept. 30 Sunday, Dec. 2 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 4 BYE at TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS WEEK 13 Sunday, Oct. 7 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Sunday, Dec. 9 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 5 vs NEW YORK GIANTS at CLEVELAND BROWNS WEEK 14 RECORDS Sunday, Oct. 14 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Monday, Dec. 17 • 8:15 pm (ESPN) WEEK 6 at WASHINGTON REDSKINS vs NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEK 15 Sunday, Oct. 21 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Sunday, Dec. 23 • 1:00 pm (FOX) WEEK 7 at PHILADELPHIA EAGLES vs ATLANTA FALCONS WEEK 16 TEAM HISTORY Sunday, Oct. 28 • 1:00 pm* (CBS) Sunday, Dec. 30 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 8 vs BALTIMORE RAVENS at NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEK 17 Sunday, Nov.