Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legends in Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 31, 2020 CONTACT: DeAnn Lubell-Ames – (760) 831-3090 Note: Photos available at http://mccallumtheatre.com/index.php/media Legends In Concert: The Divas Tributes To Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston And Aretha Franklin McCallum Theatre Thursday – February 27 – 3:00 Pm And 8:00pm Palm Desert, CA – Through the generosity of Harold Matzner, the McCallum Theatre presents Legends in Concert—The Divas, featuring tributes to Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin, for two shows: at 3:00pm and 8:00pm, Thursday, Feb. 27. Legends in Concert is the longest-running show in Las Vegas history, and after 35 years is still voted the No. 1 tribute show in the city. The internationally acclaimed and award-winning production is known as the pioneer of live tribute shows, and possesses the greatest collection of live tribute artists in the world. These incredible artists have pitch-perfect live vocals, signature choreography, and stunningly similar appearances to the legends they portray. Jazmine (Whitney Houston) draws her musical inspiration from her Cuban heritage while speaking and singing in both English and Spanish. After deciding to pursue her music career on the European music scene, she earned immediate success. After signing a one-album deal with Finland's K-TEL Records, Jazmine's first single achieved international success: In January 1996, "Love Like Never Before" rose to No. 1 on the French dance chart, dropping Madonna to No. 2 and passing same-week entries from Michael Jackson, Bon Jovi and Whitney Houston. She has appeared on the WB television show Pop Stars and on several episodes of the Dick Clark Productions show Your Big Break. -

Geuzenliedboek 1940-1945

Geuzenliedboek 1940-1945 redactie M.G. Schenk en H.M. Mos bron M.G. Schenk en H.M. Mos (red.), Geuzenliedboek 1940-1945. Buijten & Schipperheijn, Amsterdam 1975 (herdruk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/sche123geuz01_01/colofon.htm © 2008 dbnl / erven M.G. Schenk, H.M. Mos V Inleiding Een volk dat voor tirannen zwicht zal meer dan lijf en goed verliezen - dan dooft het licht Hendrik Mattheus van Randwijk (1909-1966) ‘Het onbeholpen vers door een ongeletterde binnen de gevangenismuren (of daarbuiten - red.) geschreven; het sonnet van den hoogleeraar die in het gevloekte Buchenwald - maar hoeveel heerlijk Nederlandsch gemeenschapsleven werd daar gegrondvest - voor het eerst bemerkte dat hij dichter was; het lied van de haat en het lied van het onbuigbare vertrouwen; kortom het nieuwe geuzenlied doet ons het Nederlandsche volk kennen zoals het was en is in dezen na den tachtigjarigen oorlog zwaarsten tijd van zijn bestaan. Daarom is de uitgave van Geuzenliedboeken een daad van zoo groote betekenis voor het heden, omdat duizenden daarin hun eigen gevoelens weerspiegeld vinden voor de toekomst, als onmisbare bijdrage tot de kennis van de volkspsychologie van dezen, onzen tijd’. Zo staat het in het Voorwoord tot het ‘Geuzenliedboek, derde vervolg’, dat in het oosten van het land op de pers lag, toen dit deel van Nederland bevrijd werd en dat dus niet meer illegaal verspreid behoefde te worden zoals de beide voorafgaande delen. Nu, dertig jaar later, denken wij wel iets genuanceerder; de ‘ontmythologisering’ heeft - terecht - geen halt gehouden bij de houding van het Nederlandse volk. Wij weten nu dat velen zich tamelijk afzijdig hebben gehouden ondanks hun afkeer van de bezetters, omdat die hun rustige bestaan verstoorden. -

Kunstner Titel CDG # Danseorkestret Kom Tilbage Nu Danske Karaoke

Kunstner Titel CDG # Danseorkestret Kom Tilbage Nu Danske Karaoke Hits 1 1 Brixx Video Video Danske Karaoke Hits 1 3 Poul Krebs Sådan Nogle Som Os Danske Karaoke Hits 1 5 Birthe Kjær Den knaldrøde gummibåd Danske Karaoke Hits 1 6 Bamse I en lille båd der gynger Danske Karaoke Hits 1 7 Re-Sepp-Ten Vi er røde, vi er hvide Danske Karaoke Hits 1 2 Poul Krebs Kald Det kærlighed Danske Karaoke Hits 1 8 Dansk Hip hurra Danske Karaoke Hits 1 9 Teddy Edelmann Himmelhunden Danske Karaoke Hits 1 10 John Mogensen Så længe jeg lever Danske Karaoke Hits 1 11 Dansk Æblemand Danske Karaoke Hits 1 12 Jacob Haugaard Hammer Hammer fedt Danske Karaoke Hits 1 13 Det Brune Punktum Jeg vil i seng med de fleste Danske Karaoke Hits 1 14 Rollo & King Der står et billede af dig på mit bord Danske Karaoke Hits 1 15 Kim Larsen Om lidt Danske Karaoke Hits 1 16 Mc Einar Det jul det cool Danske Karaoke Hits 1 17 Thomas Helmig Jeg Tager Imod DK Hits 4 2 Østkyst Hustlers Så Hold Dog Kæft DK Hits 4 4 Østkyst Hustlers Står Her Endnu DK Hits 4 5 Humleridderne Humletid DK Hits 4 6 Clemens Hr. Betjent DK Hits 4 7 Gnags Danmark DK Hits 4 8 Kim Larsen Papirsklip DK Hits 4 9 Paul Krebs Sådan Nogen som Os DK Hits 4 10 Birthe Kjær Pas På Den Knaldrøde Gummibåd DK Hits 4 12 Souvenirs Susanne Susanne (Jeg Hader...) DK Hits 4 13 3 Doors Down Kryptonite SPC-01 1 Nine Days Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) SPC-01 2 Santana Smooth SPC-01 3 N Sync Bye Bye Bye SPC-01 4 Backstreet Boys Show Me The Meaning Of Being Lonely SPC-01 5 Sixpence None The Richer Kiss Me SPC-01 6 Creed Highe SPC-01 7 -

Famous Abba Fans Talk: Conchita Wurst

FAMOUS ABBA FANS TALK: CONCHITAby Stany Van WURSTWymeersch by Stany Van Wymeersch To narrow down Conchita Wurst (a.k.a. Tom voice, and it is such a harmony together. Neuwirth) as the bearded drag queen who What do you consider ABBA’s greatest won the Eurovision Song Contest for Austria merit? exactly forty years after ABBA’s victory with They made easy listening pop songs which Waterloo would be quite unfair. Indeed, since never became old-fashioned. They are totally winning the ESC, Conchita has established timeless. herself on the international scene as a singer Have you got a favourite ABBA song, one INTERVIEW with an impressive vocal range, as well as a that you would like to interpret one day? gay and cultural icon. Both the private person, I love Mamma Mia! This is my number one Tom, and the adopted personality, Conchita, choice at the karaoke bar (laughs). take a strong stance in favour of tolerance and Have you ever met one of the ABBA against discrimination. Appearances, gender members? and ethnicity should not matter when it comes Unfortunately, no. But if they read these lines, to the dignity and freedom of individuals, she they probably would like to write a song for me. pointed out. They are ‘Wurst’ [meaningless], as In your opinion, why are ABBA so popular the Austrians would say. within the LGBT (Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/ Transgender) community? In your opinion, how important was ABBA’s Easy pop which works and fabulous and 1974 victory in the Eurovision Song Contest? glamorous dresses. Voilà! And who could resist I think it was an extremely important moment a song called Dancing Queen? for Eurovision. -

Nielsen Music Year-End Report Canada 2016

NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company 1 Welcome to the annual Nielsen Music Year End Report for Canada, providing the definitive 2016 figures and charts for the music industry. And what a year it was! The year had barely begun when we were already saying goodbye to musical heroes gone far too soon. David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Glenn Frey, Leon Russell, Maurice White, Prince, George Michael ... the list goes on. And yet, despite the sadness of these losses, there is much for the industry to celebrate. Music consumption is at an all-time high. Overall consumption of album sales, song sales and audio on-demand streaming volume is up 5% over 2015, fueled by an incredible 203% increase in on-demand audio streams, enough to offset declines in sales and return a positive year for the business. 2016 also marked the highest vinyl sales total to date. It was an incredible year for Canadian artists, at home and abroad. Eight different Canadian artists had #1 albums in 2016, led by Drake whose album Views was the biggest album of the year in Canada as well as the U.S. The Tragically Hip had two albums reach the top of the chart as well, their latest release and their 2005 best of album, and their emotional farewell concert in August was something we’ll remember for a long time. Justin Bieber, Billy Talent, Céline Dion, Shawn Mendes, Leonard Cohen and The Weeknd also spent time at #1. Break out artist Alessia Cara as well as accomplished superstar Michael Buble also enjoyed successes this year. -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

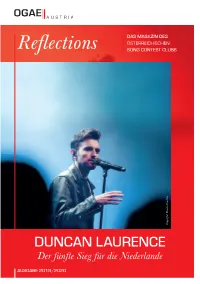

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Voor-Onze-Neus-Weggekaapt.Nl Nederlandse Woorden Gegijzeld Als Domeinnaam

Illustratie: Frank Dam Frank Illustratie: Voor-onze-neus-weggekaapt.nl Nederlandse woorden gegijzeld als domeinnaam Het is precies 25 jaar geleden dat woorden voor het eerst voorzien werden van het wilde ze vorig jaar graag Dauw.nl heb- achtervoegsel .nl. Sindsdien zijn er 4,2 miljoen van die .nldomeinnamen geregis ben, omdat ze die naam ook al voor andere doeleinden gebruikte. Die naam treerd – óók door bedrijven die ze alleen maar wilden doorverkopen. Veel namen bleek geregistreerd te zijn. “Ik heb de werden daardoor onbereikbaar voor mensen die er wél iets nuttigs mee zouden eigenaar van de naam toen gevraagd of willen doen. Hoe zit het anno 2011 met deze talige vorm van kaping? hij van de claim wilde afzien. Hij vroeg 2500 euro voor de overdracht. Ik ben daar niet op ingegaan en heb gekozen voor Dauwfotografie.nl”, aldus Zanting. Jaap Meijers freelance journalist peperduur Goedkoper.nl Antal van den Bosch hoogleraar Universiteit van Tilburg Dauw.nl was duidelijk in handen van een zogeheten domeinkaper, een han- delaar die webadressen opkoopt, in de hoop dat ooit iemand er veel geld voor wil betalen. Het is een lucratieve han- n de begindagen van internet was Er bestaan inmiddels zó veel domein- del: het grootste bedrijf in deze domein- er maar één organisatie op de we- namen dat het bijna niet meer mogelijk namenhandel, Sedo, behaalde afgelo- I reld die de zeggenschap had over is om met een zinnige naam te komen pen jaar wereldwijd een omzet van de laatste letters van internetadressen, die nog vrij is. Dat kan frustrerend zijn. -

Zug (8Th) and Basel (10Th) Rank Far Ahead of Lausanne (36Th), Bern (38Th), Zurich (41St), Lugano (53Rd), and Geneva (69Th) in the Expat City Ranking 2019

• Zug (8th) and Basel (10th) rank far ahead of Lausanne (36th), Bern (38th), Zurich (41st), Lugano (53rd), and Geneva (69th) in the Expat City Ranking 2019. • Based on the ranking, Taipei, Kuala Lumpur, Ho Chi Minh City, Singapore, Montréal, Lisbon, Barcelona, Zug, The Hague, and Basel are the best cities to move to in 2020. • Kuwait City (82nd), Rome, Milan, Lagos (Nigeria), Paris, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Lima, New York City, and Yangon (73rd) are the world’s worst cities. Munich, 3 December 2019 — Seven Swiss cities are featured in the Expat City Ranking 2019 by InterNations, the world’s largest expat community with more than 3.5 million members. They all rank among the top 20 in the world for the quality of life, receiving mostly high marks for safety, local transportation, and the environment. On the other hand, expats struggle to get settled, with Zurich and Bern even ranking among the world’s worst cities in this regard. While the local cost of living is rated negatively across the board, the performance of the Swiss cities varies more in the Finance & Housing and Urban Work Life Indices. The Expat City Ranking is based on the annual Expat Insider survey by InterNations, which is with more than 20,000 respondents in 2019 one of the most extensive surveys about living and working abroad. In 2019, 82 cities around the globe are analyzed in the survey, offering in-depth information about five areas of expat life: Quality of Urban Living, Getting Settled, Urban Work Life, Finance & Housing, and Local Cost of Living. -

Lesbian Camp 02/07

SQS Bespectacular and over the top. On the genealogy of lesbian camp 02/07 Annamari Vänskä 66 In May 2007, the foundations of the queer Eurovision world seemed to shake once again as Serbia’s representative, Queer Mirror: Perspectives Marija Šerifović inspired people all over Europe vote for her and her song “Molitva”, “Prayer”. The song was praised, the singer, daughter of a famous Serbian singer, was hailed, and the whole song contest was by many seen in a new light: removed from its flamboyantly campy gay aesthetics which seems to have become one of the main signifiers of the whole contest in recent decades. As the contest had al- ready lost the Danish drag performer DQ in the semi finals, the victory of Serbia’s subtle hymn-like invocation placed the whole contest in a much more serious ballpark. With “Molitva” the contest seemed to shrug off its prominent gay appeal restoring the contest to its roots, to the idea of a Grand Prix of European Song, where the aim has been Marija Šerifović’s performance was said to lack camp and restore the to find the best European pop song in a contest between contest to its roots, to the idea of a Grand Prix of European Song. different European nations. The serious singer posed in masculine attire: tuxedo, white riosity was appeased: not only was Šerifović identified as shirt, loosely hanging bow tie and white sneakers, and was a lesbian but also as a Romany person.1 Šerifović seemed surrounded by a chorus of five femininely coded women. -

Grappig Pril Geluk Bij Het Zwanenpaar Deze Week in De Geschiedenis

STICHTING COHERENTE Nummer 20 18 mei 2021 Pril geluk bij het zwanenpaar Let op: neem geen hulp van vreemden aan. - Heeft u tips of ideeën voor elkaar en voor in ‘De Week van Co’? Bel dan 020-4963673 of mail [email protected]. Grappig Mevrouw de Wit kwam tijdens haar dagelijkse wandeling dit prille geluk tegen. “Stuur geen hulp” Wilt u ook een foto delen? Mail naar [email protected]. Gokje wagen? Deze week in de geschiedenis Deze week vindt het Song- festival plaats. Denkt u nu • 18 mei 1857 – De Rotterdamsche Diergaarde wordt al te weten wie er gaat geopend. Tegenwoordig heet de dierentuin winnen? Diergaarde Blijdorp. Stuur het land dat volgens u het mees- • 19 mei 1972 – Ajax wint met 12-1 van Vitesse, te kans maakt naar jarenlang de grootste zege in de Eredivisie. In [email protected] of bel met oktober 2020 verbeterde Ajax het eigen re- 020-4963673 om uw antwoord door te cord door met 0-13 van VVV Venlo te winnen. geven. Doe dit voor zaterdag 22 mei • 21 mei 1927 – Charles Lindbergh voltooit de 12.00 ‘s middags. Onder de goede in- eerste non-stop solovlucht over de Atlanti- zendingen wordt een prijsje verloot. sche Oceaan. Wist u dat? Blijf in beweging Doe alle oefeningen 10x. • Het eerste songfestival vond plaats in 1956. Er deden slechts zeven landen mee. Jetty Paerl zong voor Nederland het lied ‘De vogels van Holland’, geschreven door Annie M.G. Schmidt. Deze editie werd gewonnen door Zwitserland. • Vaticaanstad zou mee mogen doen met het Songfestival, maar heeft dat nog nooit gedaan. -

Brand Guidelines Version 5-2017/2018

BRAND GUIDELINES VERSION 5-2017/2018 OPERATED BY EBU THE EUROVISION SONG CONTEST - “ A SIMPLE IDEA THAT HAS SUCCEEDED. “MARCEL BEZENÇON DIRECTOR OF THE EBU (1950-1970) AND INITIATOR OF THE EUROVISION SONG CONTEST — 2 THE NAME The name of the event in public communication is always Eurovision Song Contest. For headlines and on social media, but only when practical limitations such as character limits apply, the event can be referred to as Eurovision. The abbreviation ESC may only be used for internal communications, as it is largely unknown to the public. In some countries, the Eurovision Song Contest has a translated name, such as Eurovisie Songfestival (Dutch) or Grand Prix Eurovision de la Chanson (French). These names may be used, but only in national communication. EUROVISION SONG CONTEST BRAND GUIDELINES — 3 THE LOGO Until the 2003 Eurovision Song Contest, each Host Broadcaster designed its own logo for the contest. In 2004, the EBU introduced a generic logo, to be accompanied by a theme and supporting artwork on a year-by-year basis. The logo was designed by London-based agency JM Enternational. In 2014, the EBU introduced a revamp, the current version of the logo. It was revamped by Storytegic and implemented in collaboration with Scrn. Eurovision is set in custom typograpy Song Contest is set in Gotham Bold with +25% letter spacing and +25% word spacing EUROVISION SONG CONTEST BRAND GUIDELINES — 4 THE ECO-SYSTEM The Eurovision Song Contest generic identity consists of an eco-system with four different applications, shown below. Some basic guidelines: Ÿ The generic logo can only be used by EBU and its partners; Ÿ The event logo can only be used for a particular event by the EBU, Host Broadcaster, Participating Broadcasters and Event Partners (sponsors); Ÿ A national logo can only be used by the EBU, its partners and each respective Participating Broadcaster; Ÿ The flag heart can only be used for illustrative purposes (e.g.