Darwin's Middle Road∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

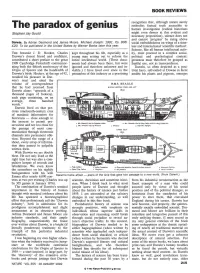

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology. -

Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(S): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S

Paleontological Society Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(s): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba Reviewed work(s): Source: Paleobiology, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 4-15 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400563 . Accessed: 27/08/2012 17:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Paleobiology. http://www.jstor.org Paleobiology,8(1), 1982, pp. 4-15 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form StephenJay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba* Abstract.-Adaptationhas been definedand recognizedby two differentcriteria: historical genesis (fea- turesbuilt by naturalselection for their present role) and currentutility (features now enhancingfitness no matterhow theyarose). Biologistshave oftenfailed to recognizethe potentialconfusion between these differentdefinitions because we have tendedto view naturalselection as so dominantamong evolutionary mechanismsthat historical process and currentproduct become one. Yet if manyfeatures of organisms are non-adapted,but available foruseful cooptation in descendants,then an importantconcept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generallyremain unconsidered):features that now enhance fitnessbut were not built by naturalselection for their current role. -

The Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Author(S): Stephen P

The neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Author(s): Stephen P. Hubbell Source: Paleobiology, 31(sp5):122-132. 2005. Published By: The Paleontological Society DOI: 10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0122:TNTOBA]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1666/0094- 8373%282005%29031%5B0122%3ATNTOBA%5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Paleobiology,31(2, Supplement),2005,pp.122±132 The neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Stephen P. Hubbell Abstract.ÐNeutral theory in ecology is based on the symmetry assumption that ecologically similar species in a community can be treated as demographically equivalent on a per capita basisÐequiv- alent in birth and death rates, in rates of dispersal, and even in the probability of speciating. Al- though only a ®rst approximation, the symmetry assumption allows the development of a quan- titative neutral theory of relative species abundance and dynamic null hypotheses for the assembly of communities in ecological time and for phylogeny and phylogeography in evolutionary time. -

Opus 200 - Stephen Jay Gould

Opus 200 - Stephen Jay Gould Natural History, August 1991, 100 (8):12-18 In my adopted home of Puritan New England, I have learned that personal indulgence is a vice to be tolerated only at rare intervals. Combine this stricture with two further principles and this essay achieves its rationale: first, that we celebrate in hundreds and their easy multiples (the Columbian quincentenary and the fiftieth anniversary of DiMaggio's hitting streak—both about equally important, and only the latter an unambiguous good); second, that geologists learn to take the long view. This is my 200th essay in "This View of Life," a series begun in January 1974 (with never an issue missed). If once is an incident and twice a tradition, I now establish an indulgence for even multiples of 100 only. Essays must express the personal thoughts and prejudices of authors—for this has been the genre's definition ever since Montaigne. But I have tried not to abuse the bully pulpit of this forum to act as a shill for my own professional research and theorizing. Still, once in a hundred shouldn't subvert my bonae fides, so I indulge, as I did once before at my own centenary. Essay 100 treated the Bahamian land snails that usurp the bulk of my time for empirical research. Opus 200 shall discuss the theoretical idea most central to my work— punctuated equilibrium. Moreover, Niles Eldredge and I formulated the theory of punctuated equilibrium in 1971, and I can scarcely resist the double whammy of 200 essays on the twentieth anniversary of "punk eke," the affectionate nickname used by supporters, while detractors have parried with "evolution by jerks." Punctuated equilibrium began, as so much else that later looms large in our lives, as a little path that might never have opened. -

Stephen Jay Gould

Commentary Stephen Jay Gould On May 20th the world lost a major thinker in the field of evolutionary biology and its foremost historian of ideas in this field. Stephen Jay Gould’s prodigiousness, breadth of knowledge and grandiloquence sometimes made him seem more like a figure of the 19th century than the 20th, but his work was critical in the transition from the neo-Darwinian synthesis to the more developmentally- influenced concepts of evolution of the present period. Gould was a keen observer of natural phenomena, and fearless in pursuing the consequences of his observations even if they led to unorthodox conclusions. Notwithstanding his many talents, he did not involve himself in the molecular approaches that emerged as the mainstream of evolutionary and developmental studies during his lifetime. This worked to his advantage, however, in that it freed him to consider large scale macroevolutionary events through the telescope of paleontology, to which he brought a new glamour, rather than the microscope of molecular genetics, where the big picture is frequently missed. Punctuated equilibrium – the fits and starts of the fossil record – was elevated by Gould and his colleague Niles Eldredge to a phenomenon that required rethinking the neo-Darwinian orthodoxy (Gould and Eldredge 1977). So was the “Burgess Shale effect”, the finding that most, if not all, the major animal body plans burst forth in a relatively narrow span of time between 500–600 million years ago (Gould 1989). The standard neo-Darwinian view (deriving primarily from theoretical work of R A Fisher) was that sudden morphological change (saltation) cannot be characteristic of evolution and there must thus be something incomplete about observations of morphological discontinuity – a consequence of gaps in the fossil record, and so forth. -

Nature, Progress and Stephen Jay Gould's Biopolitics

RRMX0893569032000163384.fm Page 479 Friday, November 21, 2003 10:02 AM RETHINKING MARXISM VOLUME 15 NUMBER 4 (OCTOBER 2003) Nature, Progress and Stephen Jay Gould’s Biopolitics Stuart A. Newman Genetic manipulation promises to introduce biological novelties to the ecosphere, the dinner plate, and the schoolroom. Is there an appropriate Left response to such eventualities? From its earliest roots in the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century, the Left has generally been favorably disposed to technology, which has been seen as having the potential to liberate workers from drudgery and foster progressive changes in social relations. There is also a countervailing (though not necessarily antagonistic) Left tradition, beginning with Luddism and allied move- ments, of skepticism about promises held out by technological change, cognizant of the capacity of new technology to increase the power of hegemonic social groups over those less empowered. Additionally, the environmental and antinuclear and biological weapons movements of the twentieth century have contributed to Left theory the notion that there are consequences of technological activity that super- sede class considerations. Global warming, nuclear winter, and pandemic infectious disease have the potential of doing away with us all, proletarian and bourgeois alike. Now that, in the twenty-first century, we have technologies with the possibility of altering not just social relations and the physical environment and ecosphere, but organismal identities themselves, a whole new set of questions has been raised about their hazards and their political and even cultural implications. Like the earlier issues raised by environmental depredation and weapons proliferation, attitudes toward genetic engineering turn out to involve commitments beyond the standard Left/Right divide. -

Evolutionary Progress: Stephen Jay Gould's Rejection and Its Critique

Philosophy Study, June 2019, Vol. 9, No. 6, 293-309 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2019.06.001 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Evolutionary Progress: Stephen Jay Gould’s Rejection and Its Critique LI Jianhui Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China In evolutionary theory, we generally believe that the evolution of life is from simple to complex, from single to diverse, and from lower to higher. Thus, the idea of evolutionary progress appears obvious. However, in contemporary academic circles, some biologists and philosophers challenge this idea. Among them, Gould is the most influential. This paper first describes Gould’s seven arguments against evolutionary progress, i.e., the human arrogance argument, anthropocentric argument, no inner thrust argument, no biological base argument, extreme contingency argument, statistical error argument, and bacteria (other than human beings) ruling the earth argument. Gould’s arguments against evolutionary progress have great influence in contemporary evolutionary theory. Thus, it is necessary to conduct a careful philosophical analysis of each of Gould’s arguments to reveal his philosophical mistakes. This research contends that Gould’s arguments against evolutionary progress are invalid. Keywords: evolution, evolutionary progress, natural selection, Stephan Jay Gould Introduction In evolutionary theory, we often have the impression that the evolution of life is from simple to complex, from single to diverse, and from lower to higher. Hence, it seems obvious that evolution is progressive. At the end of On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote: “as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection” (Darwin, 1859, p. -

An Evolutionary Perspective on Strengths, Fallacies, and Confusions in the Concept of Native Plants

An Evolutionary Perspective on Strengths, Fallacies, and Confusions in the Concept of Native Plants Stephen jay Gould An important, but widely unappreciated, concept in evolutionary biology draws a clear and careful distinction between the historical origin and current utility of organic features. Feathers, for example, could not have originated for flight because five percent of a wing in the early intermediary stages between small running dinosaurs and birds could not have served any aerodynamic function (though feathers, derived from reptilian scales, provide important thermodynamic benefits right away). But feathers were later co-opted to keep birds aloft in a most exemplary fashion. In like manner, our large brains could not have evolved in order to permit modern descendants to read and write, though these much later functions now define an important part of modern utility. Similarly, the later use of an argument, often in a context foreign or even opposite to the intent of originators, must be separated from the validity and purposes of initial formula- tions. Thus, for example, Darwin’s theory of natural selection is not diminished because later racists and warmongers perverted the concept of a "struggle for existence" into a ration- ale for genocide. However, we must admit a crucial difference between the two cases: the origin and later use of a biological feature, and the origin and later use of an idea. The first case involves no conscious intent and cannot be submitted to any moral judgment. But ideas are developed by human beings for overt purposes, and we have some ethical responsibility for the consequences of our actions. -

A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 61 Issue 5 Issue 5 - October 2008 Article 1 10-2008 A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution Scott Dodson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Scott Dodson, A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution, 61 Vanderbilt Law Review 1319 (2008) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol61/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 61 OCTOBER 2008 NUMBER 5 A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution Scott Dodson* I. INTRODU CTION ................................................................... 1320 II. THE METAPHOR OF A "LIVING" CONSTITUTION .................. 1322 III. EVALUATING THE METAPHOR ............................................. 1325 A. MetaphoricalAccuracies and Gaps ........................ 1326 B. ConstitutionalEvolution? ....................................... 1327 1. By Natural Selection ................................... 1329 2. O ther O ptions .............................................. 1333 a. Artificial Selection ............................ 1333 b. Intelligent Design ............................. 1335 c. Hybridization.................................... 1337 IV. EXTENDING THE METAPHOR .............................................. -

Evolution the Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm

Evolution The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme STEPHEN JAY GOULD AND RICHARD C. LEWONTIN REPUBLISHED FROM THE ORIGINAL WITH THE KIND PERMISSION OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON: GOULD, S. J. AND LEWONTIN, R. C., "THE SPANDRELS OF SAN MARCO AND THE PANGLOSSIAN PARADIGM: A CRITIQUE OF THE ADAPTATIONIST PROGRAMME," PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, SERIES B, VOL. 205, NO. 1161 (1979), PP. 581-598. An adaptationist programme has dominated evolutionary thought in England and the United States during the past forty years. It is based on faith in the power of natural selection as an optimizing agent. It proceeds by breaking an organism into unitary "traits" and proposing an adaptive story for each considered separately. Trade-offs among competing selective demands exert the only brake upon perfection; nonoptimality is thereby rendered as a result of adaptation as well. We criticize this approach and attempt to reassert a competing notion (long popular in continental Europe) that organisms must be analyzed as integrated wholes, with baupläne so constrained by phyletic heritage, pathways of development, and general architecture that the constraints themselves become more interesting and more important in delimiting pathways of change than the selective force that may mediate change when it occurs. We fault the adaptationist programme for its failure to distinguish current utility from reasons for origin (male tyrannosaurs may have used their diminutive front legs to titillate -

George Gaylord Simpson and the Invention of Modern Paleontology

Momentum Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 5 2012 Defining a Discipline: George Gaylord Simpson and the Invention of Modern Paleontology William S. Kearney [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum Recommended Citation Kearney, William S. (2012) "Defining a Discipline: George Gaylord Simpson and the Invention of Modern Paleontology," Momentum: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol1/iss2/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol1/iss2/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Defining a Discipline: George Gaylord Simpson and the Invention of Modern Paleontology Abstract Kearney studies how the paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson worked to define his own field of evolutionary paleontology. This journal article is available in Momentum: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol1/iss2/5 Kearney: Defining a Discipline: George Gaylord Simpson and the Invention o 1 Defining a Discipline George Gaylord Simpson and the Invention of Modern Paleontology William S. Kearney The synthesis of Darwinian evolution by natural selection and Mendelian genetics was the crowning achievement of early 20th century biology. It gave an underlying theoretical basis for every major field of biology from molecular biology to zoology to community ecology. And by no means was the synthesis the work of one man. American, British, German and Russian geneticists, naturalists, and mathematicians all provided major theoretical contributions to the synthesis. But in paleontology it was a different story. One man, George Gaylord Simpson, in one book, Tempo and Mode in Evolution, effectively synthesized evolutionary biology and paleontology.