Biological Determinism and the Essays of Stephen Jay Gould

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

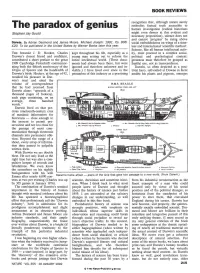

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

SOHASKY-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (2.074Mb)

DIFFERENTIAL MINDS: MASS INTELLIGENCE TESTING AND RACE SCIENCE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Kate E. Sohasky A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland May 9, 2017 © Kate E. Sohasky All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Historians have argued that race science and eugenics retreated following their discrediting in the wake of the Second World War. Yet if race science and eugenics disappeared, how does one explain their sudden and unexpected reemergence in the form of the neohereditarian work of Arthur Jensen, Richard Herrnstein, and Charles Murray? This dissertation argues that race science and eugenics did not retreat following their discrediting. Rather, race science and eugenics adapted to changing political and social climes, at times entering into states of latency, throughout the twentieth century. The transnational history of mass intelligence testing in the twentieth century demonstrates the longevity of race science and eugenics long after their discrediting. Indeed, the tropes of race science and eugenics persist today in the modern I.Q. controversy, as the dissertation shows. By examining the history of mass intelligence testing in multiple nations, this dissertation presents narrative of the continuity of race science and eugenics throughout the twentieth century. Dissertation Committee: Advisors: Angus Burgin and Ronald G. Walters Readers: Louis Galambos, Nathaniel Comfort, and Adam Sheingate Alternates: François Furstenberg -

Psychometric G: Definition and Substantiation

Psychometric g: Definition and Substantiation Arthur R. Jensen University of Culifornia, Berkeley The construct known as psychometric g is arguably the most important construct in all of psychology largelybecause of its ubiquitous presence in all tests of mental ability and its wide-ranging predictive validity for a great many socially significant variables, including scholastic performance and intellectual attainments, occupational status, job performance, in- come, law abidingness, and welfare dependency. Even such nonintellec- tual variables as myopia, general health, and longevity, as well as many other physical traits, are positively related to g. Of course, the causal con- nections in the whole nexus of the many diverse phenomena involving the g factor is highly complex. Indeed, g and its ramifications cut across the behavioral sciences-brainphysiology, psychology, sociology-perhaps more than any other scientific construct. THE DOMAIN OF g THEORY It is important to keep in mind the distinction between intelligence and g, as these terms are used here. The psychology of intelligence could, at least in theory, be based on the study of one person,just as Ebbinghaus discov- ered some of the laws of learning and memory in experimentswith N = 1, using himself as his experimental subject. Intelligence is an open-ended category for all those mental processes we view as cognitive, such as stimu- lus apprehension, perception, attention, discrimination, generalization, 39 40 JENSEN learning and learning-set acquisition, short-term and long-term memory, inference, thinking, relation eduction, inductive and deductive reasoning, insight, problem solving, and language. The g factor is something else. It could never have been discovered with N = 1, because it reflects individual di,fferences in performance on tests or tasks that involve anyone or moreof the kinds of processes just referred to as intelligence. -

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution a Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused by Dr

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution A Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused By Dr. Mike Webster, Dept. of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University ([email protected]); February 2010 The current debate over evolution and “intelligent design” (ID) is being driven by a relatively small group of individuals who object to the theory of evolution for religious reasons. The debate is fueled, though, by misunderstandings on the part of the American public about what evolutionary biology is and what it says. These misunderstandings are exploited by proponents of ID, intentionally or not, and are often echoed in the media. In this booklet I briefly outline and explain 10 of the most common (and serious) misunderstandings. It is impossible to treat each point thoroughly in this limited space; I encourage you to read further on these topics and also by visiting the websites given on the resource sheet. In addition, I am happy to send a somewhat expanded version of this booklet to anybody who is interested – just send me an email to ask for one! What are the misunderstandings? 1. Evolution is progressive improvement of species Evolution, particularly human evolution, is often pictured in textbooks as a string of organisms marching in single file from “simple” organisms (usually a single celled organism or a monkey) on one side of the page and advancing to “complex” organisms on the opposite side of the page (almost invariably a human being). We have all seen this enduring image and likely have some version of it burned into our brains. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology. -

John Vandermeer

JOHN VANDERMEER - THE DIALECTICS OF ECOLOGY: BIOLOGICAL, HISTORICAL AND POLITICAL INTERSECTIONS PUBLICATIONS OF ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SPECIAL PUBLICATION NO. 1 GERALD SMITH, Editor LINDA GARCIA, Managing Editor ELIZABETH WASON AND KATHERINE LOUGHNEY, Proofreaders GORDON FITCH AND MACKENZIE SCHONDLEMAYER, Cover graphics The publications of the Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, consist primarily of two series—the Miscellaneous Publications and the Occasional Papers. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. Occasionally the Museum publishes contributions outside of these series. Beginning in 1990 these are titled Special Publications and Circulars and each are sequentially numbered. All submitted manuscripts to any of the Museum’s publications receive external peer review. The Occasional Papers, begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, initiated in 1916, include monographic studies, papers on field and museum techniques, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, and are published separately. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians, Fishes, Insects, Mollusks, and other topics is available. Address inquiries to Publications, Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109–1079. -

The New Eugenics: Black Hyper-Incarceration and Human Abatement

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The New Eugenics: Black Hyper-Incarceration and Human Abatement James C. Oleson Department of Sociology, The University of Auckland, Level 9, HSB Building, 10 Symonds Street, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; [email protected]; Tel.: +64-937-375-99 Academic Editor: Bryan L. Sykes Received: 14 June 2016; Accepted: 20 October 2016; Published: 25 October 2016 Abstract: In the early twentieth century, the eugenics movement exercised considerable influence over domestic US public policy. Positive eugenics encouraged the reproduction of “fit” human specimens while negative eugenics attempted to reduce the reproduction of “unfit” specimens like the “feebleminded” and the criminal. Although eugenics became a taboo concept after World War II, it did not disappear. It was merely repackaged. Incarceration is no longer related to stated eugenic goals, yet incapacitation in prisons still exerts a prophylactic effect on human reproduction. Because minorities are incarcerated in disproportionately high numbers, the prophylactic effect of incarceration affects them most dramatically. In fact, for black males, the effect of hyper-incarceration might be so great as to depress overall reproduction rates. This article identifies some of the legal and extralegal variables that would be relevant for such an analysis and calls for such an investigation. Keywords: eugenics; race; ethnicity; incarceration; prison; prophylactic effect “[W]hen eugenics reincarnates this time, it will not come through the front door, as with Hitler’s Lebensborn project. Instead, it will come by the back door...” ([1], p. x). 1. Introduction At year-end 2014, more than 2.2 million people were incarcerated in US jails and prisons [2], confined at a rate of 698 persons per 100,000 [3]. -

AFRICAN WOMEN UNDER APARTHEID* by Fassil Demissie Introduction Over the Last Decade, One of the Notable Features

DOUBLE BURDEN: AFRICAN WOMEN UNDER APARTHEID* by Fassil Demissie Introduction over the last decade, one of the notable features of research on the study of the social and economic history of South Africa has been the steady emergence of a body of writing focusing on issues related to women. Much of the renewed interest owes to the critical scholarship that emerged during the late 1960s which focused on delineating the international and national structures of domination and subordination. In addition, increased interest in marxist works has added to a greater understanding of the sexual division of labor and the subordination of women. In the Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State Engels sketched the development of private property, the economic unit Of Which became the family t and the transformation of the role of women to a subordinated and dependent position. Engels attempted to show how the transformation of the role of women from the position of equality to subordination brought about the "world historical defeat of the femal sex." His project, although sketchy was to draw an explicit connection between the changes in the form of the family (and women's role within it) on the one hand and changes in property and class relations on the other. In fact, the intent of The Origin of the Family is to identify the stages a.nd substages in the development of increasingly advanced labor techniques and the effect of these advances on kinship relations. Engels suggested that in "primitive societies" property was collectively owned and both sexes made equal contributions to the larger group which was identified by kinship relations and common territorial residence. -

The Black-White Test Score Gap: an Introduction

CHRISTOPHER JENCKS MEREDITH PHILLIPS 1 The Black-White Test Score Gap: An Introduction FRICAN AMERICANS currently score lower than A European Americans on vocabulary, reading, and mathematics tests, as well as on tests that claim to measure scholastic apti- tude and intelligence.1 This gap appears before children enter kindergarten (figure 1-1), and it persists into adulthood. It has narrowed since 1970, but the typical American black still scores below 75 percent of American whites on most standardized tests.2 On some tests the typical American black scores below more than 85 percent of whites.3 1. We are indebted to Karl Alexander, William Dickens, Ronald Ferguson, James Flynn, Frank Furstenberg, Arthur Goldberger, Tom Kane, David Levine, Jens Ludwig, Richard Nisbett, Jane Mansbridge, Susan Mayer, Claude Steele, and Karolyn Tyson for helpful criticisms of earlier drafts. But we did not make all the changes they suggested, and they are in no way responsible for our conclusions. 2. These statistics also imply, of course, that a lot of blacks score above a lot of whites. If the black and white distributions are normal and have the same standard deviation, and if the black-white gap is one (black or white) standard deviation, then when we compare a randomly selected black to a randomly selected white, the black will score higher than the white about 24 percent of the time. If the black-white gap is 0.75 rather than 1.00 standard deviations, a randomly selected black will score higher than a randomly selected white about 30 percent of the time. -

Dinosaur in a Haystack

Dinosaur In a Haystack DIH 1. Happy Thoughts on a Sunny Day in New York City ............................................. 1 DIH 2. Dousing Diminutive Dennis’s Debate (or DDDD = 2000) .................................... 2 DIH 3. The Celestial Mechanic and the Earthly Naturalist ................................................ 3 DIH 4. The Late Birth of a Flat Earth ................................................................................. 4 DIH 5. The Monster’s Human Nature ................................................................................ 5 DIH 6. The Tooth and Claw Centennial ............................................................................. 6 DIH 7. Sweetness and Light ............................................................................................... 7 DIH 8. In the Mind of the Beholder .................................................................................... 8 DIH 9. Of Tongue Worms, Velvet Worms, and Water Bears .......................................... 10 DIH 10. Cordelia’s Dilemma ............................................................................................ 12 DIH 11. Lucy on the Earth in Stasis ................................................................................. 14 DIH 12. Dinosaur in a Haystack ....................................................................................... 15 DIH 13. Jove’s Thunderbolts ............................................................................................ 18 DIH 14. Poe’s Greatest Hit .............................................................................................. -

Genes, Race, and History JONATHAN MARKS

FOUNDATIONS OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR An Aldine de Gruyter Series of Texts and Monographs SERIES EDITORS Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, University of California, Davis Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, University of California, Davis Richard D. Alexander, The Biology of Moral Systems Laura L. Betzig, Despotism and Differential Reproduction: A Darwinian View of History Russell L. Ciochon and John G. Fleagle (Eds.), Primate Evolution and Human Origins Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, Homicide Irensus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Human Ethology Richard J. Gelles and Jane B. Lancaster (Eds,), Child Abuse and Neglect: Biosocial Dimensions Kathleen R. Gibson and Anne C. Petersen (Eds.), Brain Maturation and Cognitive Development: Comparative and Cross-Cultural Perspectives Barry S, Hewlett (Ed.), Father-Child Relations: Cultural and Biosocial Contexts Warren G. Kinzey (Ed.), New World Primates: Ecology, Evolution and Behavior Kim Hill and A. Magdalena Hurtado: Ache Life History: The Ecology and Demography of a Foraging People Jane B. Lancaster, Jeanne Altmann, Alice S. Rossi, and Lonnie R. Sherrod (Eds.), Parenting Across the Life Span: Biosocial Dimensions Jane B. Lancaster and Beatrix A. Hamburg (Eds.), School Age Pregnancy and Parenthood: Biosocial Dimensions Jonathan Marks, Human Biodiversity: Genes, Race, and History Richard B. Potts, Early Hominid Activities at Olduvai Eric Alden Smith, Inujjuamiut Foraging Strategies Eric Alden Smith and Bruce Winterhalder (Eds.), Evolutionary Ecology and Human Behavior Patricia Stuart-Macadam and Katherine Dettwyler, Breastfeeding: A Bioaftural Perspective Patricia Stuart-Macadam and Susan Kent (Eds.), Diet, Demography, and Disease: Changing Perspectives on Anemia Wenda R. Trevathan, Human Birth: An Evolutionary Perspective James W. Wood, Dynamics of Human Reproduction: Biology, Biometry, Demography HulMAN BIODIVERS~ Genes, Race, and History JONATHAN MARKS ALDINE DE GRUYTER New York About the Author Jonathan Marks is Visiting Associate Professorof Anthropology, at the University of California, Berkeley. -

Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(S): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S

Paleontological Society Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(s): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba Reviewed work(s): Source: Paleobiology, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 4-15 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400563 . Accessed: 27/08/2012 17:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Paleobiology. http://www.jstor.org Paleobiology,8(1), 1982, pp. 4-15 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form StephenJay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba* Abstract.-Adaptationhas been definedand recognizedby two differentcriteria: historical genesis (fea- turesbuilt by naturalselection for their present role) and currentutility (features now enhancingfitness no matterhow theyarose). Biologistshave oftenfailed to recognizethe potentialconfusion between these differentdefinitions because we have tendedto view naturalselection as so dominantamong evolutionary mechanismsthat historical process and currentproduct become one. Yet if manyfeatures of organisms are non-adapted,but available foruseful cooptation in descendants,then an importantconcept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generallyremain unconsidered):features that now enhance fitnessbut were not built by naturalselection for their current role.