The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

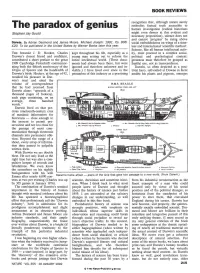

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

Available Generic Names for Trilobites

AVAILABLE GENERIC NAMES FOR TRILOBITES P.A. JELL AND J.M. ADRAIN Jell, P.A. & Adrain, J.M. 30 8 2002: Available generic names for trilobites. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 48(2): 331-553. Brisbane. ISSN0079-8835. Aconsolidated list of available generic names introduced since the beginning of the binomial nomenclature system for trilobites is presented for the first time. Each entry is accompanied by the author and date of availability, by the name of the type species, by a lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic and geographic reference for the type species, by a family assignment and by an age indication of the type species at the Period level (e.g. MCAM, LDEV). A second listing of these names is taxonomically arranged in families with the families listed alphabetically, higher level classification being outside the scope of this work. We also provide a list of names that have apparently been applied to trilobites but which remain nomina nuda within the ICZN definition. Peter A. Jell, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland 4101, Australia; Jonathan M. Adrain, Department of Geoscience, 121 Trowbridge Hall, Univ- ersity of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA; 1 August 2002. p Trilobites, generic names, checklist. Trilobite fossils attracted the attention of could find. This list was copied on an early spirit humans in different parts of the world from the stencil machine to some 20 or more trilobite very beginning, probably even prehistoric times. workers around the world, principally those who In the 1700s various European natural historians would author the 1959 Treatise edition. Weller began systematic study of living and fossil also drew on this compilation for his Presidential organisms including trilobites. -

What Is a Species, and What Is Not? Ernst Mayr Philosophy of Science

What Is a Species, and What Is Not? Ernst Mayr Philosophy of Science, Vol. 63, No. 2. (Jun., 1996), pp. 262-277. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8248%28199606%2963%3A2%3C262%3AWIASAW%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Philosophy of Science is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Aug 21 14:59:32 2007 WHAT IS A SPECIES, AND WHAT IS NOT?" ERNST MAYRT I analyze a number of widespread misconceptions concerning species. -

Systematics in Palaeontology

Systematics in palaeontology THOMAS NEVILLE GEORGE PRESIDENT'S ANNIVERSARY ADDRESS 1969 CONTENTS Fossils in neontological categories I98 (A) Purpose and method x98 (B) Linnaean taxa . x99 (e) The biospecies . 202 (D) Morphology and evolution 205 The systematics of the lineage 205 (A) Bioserial change 205 (B) The palaeodeme in phyletic series 209 (e) Palaeodemes as facies-controlled phena 2xi Phyletic series . 2~6 (A) Rates of bioserial change 2~6 (B) Character mosaics 218 (c) Differential characters 222 Phylogenetics and systematics 224 (A) Clade and grade 224 (a) Phylogenes and cladogenes 228 (e) Phylogenetic reconstruction 23 I (D) Species and genus 235 (~) The taxonomic hierarchy 238 5 Adansonian methods 240 6 References 243 SUMMARY A 'natural' taxonomic system, inherent in evolutionary change, pulses of biased selection organisms that themselves demonstrate their pressure in expanded and restricted palaeo- 'affinity', is to be recognized perhaps only in demes, and permutations of character-expres- the biospecies. The concept of the biospecies as sion in the evolutionary plexus impose a need a comprehensive taxon is, however, only for a palaeontologically-orientated systematics notional amongst the vast majority of living under which (in evolutionary descent) could organisms, and it is not directly applicable to be subsumed the taxa of the neontological fossils. 'Natural' systems of Linnaean kind rest moment. on assumptions made a priori and are imposed Environmentally controlled morphs, bio- by the systematist. The graded time-sequence facies variants, migrating variation fields, and of the lineage and the clade introduces factors typological segregants are sources of ambiguity into a systematics that cannot well be accommo- in a distinction between phenetic and genetic dated under pre-Darwinian assumptions or be fossil grades. -

Springer A++ Viewer

PublisherInfo PublisherName : BioMed Central PublisherLocation : London PublisherImprintName : BioMed Central Stephen Jay Gould dies ArticleInfo ArticleID : 4486 ArticleDOI : 10.1186/gb-spotlight-20020522-01 ArticleCitationID : spotlight-20020522-01 ArticleSequenceNumber : 152 ArticleCategory : Research news ArticleFirstPage : 1 ArticleLastPage : 3 RegistrationDate : 2002–5–22 ArticleHistory : OnlineDate : 2002–5–22 ArticleCopyright : BioMed Central Ltd2002 ArticleGrants : ArticleContext : 130593311 Hal Cohen Email: [email protected] PHILADELPHIA - Stephen Jay Gould, paleontologist, evolutionary biologist and popular author, died of abdominal mesothelioma Monday in New York City. He was 60. A provocative and controversial thinker, Gould was a fierce public defender of evolution. He became a figurehead for paleontology by making difficult concepts more digestible for the public in forums such as The New York Times and The New York Review of Books. While in graduate school, Gould and fellow student Niles Eldredge disputed the theories of evolution, which held that changes in organisms only occurred gradually, over eons. In their theory, known as punctuated equilibrium, evolution proceeded in bursts, followed by long periods of stasis. Thirty years later after their theory was first developed, the debate still rages. Among the many awards and honors bestowed upon Gould were membership in the National Academy of Sciences, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He also served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Gould wrote more than a dozen books, most recently publishing the 1,454-page The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Harvard, 2001) and, this month, I Have Landed : The End of a Beginning in Natural History (Harmony Books, 2002). -

Modelling the Evolution and Expected Lifetime of a Deme's Principal Gene

Letters in Biomathematics, 2015 Vol. 2, No. 1, 13–28, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23737867.2015.1040859 RESEARCH ARTICLE Modelling the evolution and expected lifetime of a deme’s principal gene sequence B.K. Clark∗ Department of Physics, Illinois State University, Normal, IL, USA (Received 3 April 2015; accepted 10 April 2015) The principal gene sequence (PGS), defined as the most common gene sequence in a deme, is replaced over time because new gene sequences are created and compete with the current PGS, and a small fraction become PGSs. We have developed a set of coupled difference equations to represent an ensemble of demes, in which new gene sequences are introduced via chromosomal inversions. The set of equations used to calculate the expected lifetime of an existing PGS include inversion size and rate, recombination rate and deme size. Inversion rate and deme size effects are highlighted in this work. Our results compare favourably with a cellular automaton-based representation of a deme. Keywords: inversion; recombination; gene sequence; stasipatric speciation 1. Introduction Chromosomal inversions are examples of a broader group of chromosomal rearrangements. Stasipatric speciation is when chromosomal inversions are the primary mechanism of speciation (White, 1978); however, examples of speciation typically include chromosomal inversions only as a contributing factor. Examples are ubiquitous, including Drosophila (Ayala & Coluzzi, 2005; Noor, Grams, Bertucci, & Reiland, 2001; Ranz et al., 2007), sunflowers (Rieseberg, 2001; Rieseberg et al., 2003), and primates (Ayala & Coluzzi, 2005; Lee, Han, Meyer, Kim, & Batzer, 2008; Navarro & Barton, 2003a, 2003b), for example. Suppressed recombination of inverted chromosome segments has been investigated as a speciation mechanism (Ayala & Coluzzi, 2005; Navarro & Barton, 2003a, 2003b), and the precise role of inversions in speciation is still debated (Faria & Navarro, 2010). -

The Ordovician Succession Adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen

1 2 The Ordovician succession adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen 3 4 Björn Kröger1, Seth Finnegan2, Franziska Franeck3, Melanie J. Hopkins4 5 6 Abstract: The Ordovician sections along the western shore of the Hinlopen Strait, Ny 7 Friesland, were discovered in the late 1960s and since then prompted numerous 8 paleontological publications; several of them are now classical for the paleontology of 9 Ordovician trilobites, and Ordovician paleogeography and stratigraphy. Our 2016 expedition 10 aimed in a major recollection and reappraisal of the classical sites. Here we provide a first 11 high-resolution lithological description of the Kirtonryggen and Valhallfonna formations 12 (Tremadocian –Darriwilian), which together comprise a thickness of 843 m, a revised bio-, 13 and lithostratigraphy, and an interpretation of the depositional sequences. We find that the 14 sedimentary succession is very similar to successions of eastern Laurentia; its Tremadocian 15 and early Floian part is composed of predominantly peritidal dolostones and limestones 16 characterized by ribbon carbonates, intraclastic conglomerates, microbial laminites, and 17 stromatolites, and its late Floian to Darriwilian part is composed of fossil-rich, bioturbated, 18 cherty mud-wackestone, skeletal grainstone and shale, with local siltstone and glauconitic 19 horizons. The succession can be subdivided into five third-order depositional sequences, 20 which are interpreted as representing the SAUK IIIB Supersequence known from elsewhere 21 on the Laurentian -

What Is a Population? an Empirical Evaluation of Some Genetic Methods for Identifying the Number of Gene Pools and Their Degree of Connectivity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 2006 What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity Robin Waples NOAA, [email protected] Oscar Gaggiotti Université Joseph Fourier, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Waples, Robin and Gaggiotti, Oscar, "What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity" (2006). Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. 463. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/463 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Molecular Ecology (2006) 15, 1419–1439 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02890.x INVITEDBlackwell Publishing Ltd REVIEW What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity ROBIN S. WAPLES* and OSCAR GAGGIOTTI† *Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Blvd East, Seattle, WA 98112 USA, †Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (LECA), Génomique des Populations et Biodiversité, Université Joseph Fourier, Grenoble, France Abstract We review commonly used population definitions under both the ecological paradigm (which emphasizes demographic cohesion) and the evolutionary paradigm (which emphasizes reproductive cohesion) and find that none are truly operational. -

Stephen J. Gould's Legacy

STEPHEN J. GOULD’S LEGACY NATURE, HISTORY, SOCIETY Venice, May 10–12, 2012 Organized by Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti in collaboration with Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia ABSTRACTS Organizing Committee Gian Antonio Danieli, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Elena Gagliasso, Sapienza Università di Roma Alessandro Minelli, Università degli studi di Padova and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Telmo Pievani, Università degli studi di Milano Bicocca and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Maria Turchetto, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Chairpersons Bernardino Fantini, Université de Genève Marco Ferraguti, Università degli studi di Milano Elena Gagliasso, Sapienza Università di Roma Giorgio Manzi, Sapienza Università di Roma Alessandro Minelli, Università degli studi di Padova and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Telmo Pievani, Università degli studi di Milano Bicocca and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Maria Turchetto, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Invited speakers Guido Barbujani, Università degli studi di Ferrara Marcello Buiatti, Università degli studi di Firenze Andrea Cavazzini, Université de Liège Niles Eldredge, American Museum of Natural History, New York T. Ryan Gregory, University of Guelph Alberto Gualandi, Università degli studi di Bologna Elisabeth Lloyd, Indiana University Giuseppe Longo, CNRS; École Normale Supérieure, Paris Winfried Menninghaus, Freie Universität Berlin Alessandro Minelli, Università degli studi di Padova and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Gerd Müller, Konrad Lorenz Institute, Vienna and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Marco Pappalardo, McGill University, Montreal Telmo Pievani, Università degli studi di Milano Bicocca and Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti Klaus Scherer, Université de Genève Ian Tattersall, American Museum of Natural History, New York May 20, 2012 will be the tenth anniversary of Stephen Jay Gould’s death. -

Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(S): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S

Paleontological Society Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(s): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba Reviewed work(s): Source: Paleobiology, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 4-15 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400563 . Accessed: 27/08/2012 17:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Paleobiology. http://www.jstor.org Paleobiology,8(1), 1982, pp. 4-15 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form StephenJay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba* Abstract.-Adaptationhas been definedand recognizedby two differentcriteria: historical genesis (fea- turesbuilt by naturalselection for their present role) and currentutility (features now enhancingfitness no matterhow theyarose). Biologistshave oftenfailed to recognizethe potentialconfusion between these differentdefinitions because we have tendedto view naturalselection as so dominantamong evolutionary mechanismsthat historical process and currentproduct become one. Yet if manyfeatures of organisms are non-adapted,but available foruseful cooptation in descendants,then an importantconcept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generallyremain unconsidered):features that now enhance fitnessbut were not built by naturalselection for their current role. -

Darwin's Middle Road∗

Stephen Jay Gould DARWIN'S MIDDLE ROAD∗ "We began to sail up the narrow strait lamenting," narrates Odysseus. "For on the one hand lay Scylla, with twelve feet all dangling down; and six necks exceeding long, and on each a hideous head, and therein three rows of teeth set thick and close, full of black death. And on the other mighty Charybdis sucked down the salt sea water. As often as she belched it forth, like a cauldron on a great fire she would seethe up through all her troubled deeps." Odysseus managed to swerve around Charybdis, but Scylla grabbed six of his finest men and devoured them in his sight-"the most pitiful thing mine eyes have seen of all my travail in searching out the paths of the sea." False lures and dangers often come in pairs in our legends and metaphors—consider the frying pan and the fire, or the devil and the deep blue sea. Prescriptions for avoidance either emphasize a dogged steadiness—the straight and narrow of Christian evangelists—or an averaging between unpleasant alternatives—the golden mean of Aristotle. The idea1 of steering a course between undesirable extremes emerges as a central prescription for a sensible life. The nature of scientific creativity is both a perennial topic of discussion and a prime candidate for seeking a golden mean. The two extreme positions have not been directly competing for allegiance of the unwary. They have, rather, replaced each other sequentially, with one now in the ascendancy, the other eclipsed. The first—inductivism—held that great scientists are primarily great observers and patient accumulators of information. -

Th TRILO the Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILO BITES

With regard to human interest in fossils, trilobites may rank second only to dinosaurs. Having studied trilobites most of my life, the English version of The Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILOBITES by Enrico Bonino and Carlo Kier is a pleasant treat. I am captivated by the abundant color images of more than 600 diverse species of trilobites, mostly from the authors’ own collections. Carlo Kier The Back to the Past Museum Guide to Specimens amply represent famous trilobite localities around the world and typify forms from most of the Enrico Bonino Enrico 250-million-year history of trilobites. Numerous specimens are masterpieces of modern professional preparation. Richard A. Robison Professor Emeritus University of Kansas TRILOBITES Enrico Bonino was born in the Province of Bergamo in 1966 and received his degree in Geology from the Depart- ment of Earth Sciences at the University of Genoa. He currently lives in Belgium where he works as a cartographer specialized in the use of satellite imaging and geographic information systems (GIS). His proficiency in the use of digital-image processing, a healthy dose of artistic talent, and a good knowledge of desktop publishing software have provided him with the skills he needed to create graphics, including dozens of posters and illustrations, for all of the displays at the Back to the Past Museum in Cancún. In addition to his passion for trilobites, Enrico is particularly inter- TRILOBITES ested in the life forms that developed during the Precambrian. Carlo Kier was born in Milan in 1961. He holds a degree in law and is currently the director of the Azul Hotel chain.