Speciation and Bursts of Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Size and the Rate of Evolution

Review Population size and the rate of evolution 1,2 1 3 Robert Lanfear , Hanna Kokko , and Adam Eyre-Walker 1 Ecology Evolution and Genetics, Research School of Biology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia 2 National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, NC, USA 3 School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK Does evolution proceed faster in larger or smaller popu- mutations occur and the chance that each mutation lations? The relationship between effective population spreads to fixation. size (Ne) and the rate of evolution has consequences for The purpose of this review is to synthesize theoretical our ability to understand and interpret genomic varia- and empirical knowledge of the relationship between tion, and is central to many aspects of evolution and effective population size (Ne, Box 1) and the substitution ecology. Many factors affect the relationship between Ne rate, which we term the Ne–rate relationship (NeRR). A and the rate of evolution, and recent theoretical and positive NeRR implies faster evolution in larger popula- empirical studies have shown some surprising and tions relative to smaller ones, and a negative NeRR implies sometimes counterintuitive results. Some mechanisms the opposite (Figure 1A,B). Although Ne has long been tend to make the relationship positive, others negative, known to be one of the most important factors determining and they can act simultaneously. The relationship also the substitution rate [5–8], several novel predictions and depends on whether one is interested in the rate of observations have emerged in recent years, causing some neutral, adaptive, or deleterious evolution. Here, we reassessment of earlier theory and highlighting some gaps synthesize theoretical and empirical approaches to un- in our understanding. -

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B. M ü ller, G ü nter P. Wagner, and Werner Callebaut, editors The Evolution of Cognition , edited by Cecilia Heyes and Ludwig Huber, 2000 Origination of Organismal Form: Beyond the Gene in Development and Evolutionary Biology , edited by Gerd B. M ü ller and Stuart A. Newman, 2003 Environment, Development, and Evolution: Toward a Synthesis , edited by Brian K. Hall, Roy D. Pearson, and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2004 Evolution of Communication Systems: A Comparative Approach , edited by D. Kimbrough Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2004 Modularity: Understanding the Development and Evolution of Natural Complex Systems , edited by Werner Callebaut and Diego Rasskin-Gutman, 2005 Compositional Evolution: The Impact of Sex, Symbiosis, and Modularity on the Gradualist Framework of Evolution , by Richard A. Watson, 2006 Biological Emergences: Evolution by Natural Experiment , by Robert G. B. Reid, 2007 Modeling Biology: Structure, Behaviors, Evolution , edited by Manfred D. Laubichler and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2007 Evolution of Communicative Flexibility: Complexity, Creativity, and Adaptability in Human and Animal Communication , edited by Kimbrough D. Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2008 Functions in Biological and Artifi cial Worlds: Comparative Philosophical Perspectives , edited by Ulrich Krohs and Peter Kroes, 2009 Cognitive Biology: Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives on Mind, Brain, and Behavior , edited by Luca Tommasi, Mary A. Peterson, and Lynn Nadel, 2009 Innovation in Cultural Systems: Contributions from Evolutionary Anthropology , edited by Michael J. O ’ Brien and Stephen J. Shennan, 2010 The Major Transitions in Evolution Revisited , edited by Brett Calcott and Kim Sterelny, 2011 Transformations of Lamarckism: From Subtle Fluids to Molecular Biology , edited by Snait B. -

IN EVOLUTION JACK LESTER KING UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA This Paper Is Dedicated to Retiring University of California Professors Curt Stern and Everett R

THE ROLE OF MUTATION IN EVOLUTION JACK LESTER KING UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA This paper is dedicated to retiring University of California Professors Curt Stern and Everett R. Dempster. 1. Introduction Eleven decades of thought and work by Darwinian and neo-Darwinian scientists have produced a sophisticated and detailed structure of evolutionary ,theory and observations. In recent years, new techniques in molecular biology have led to new observations that appear to challenge some of the basic theorems of classical evolutionary theory, precipitating the current crisis in evolutionary thought. Building on morphological and paleontological observations, genetic experimentation, logical arguments, and upon mathematical models requiring simplifying assumptions, neo-Darwinian theorists have been able to make some remarkable predictions, some of which, unfortunately, have proven to be inaccurate. Well-known examples are the prediction that most genes in natural populations must be monomorphic [34], and the calculation that a species could evolve at a maximum rate of the order of one allele substitution per 300 genera- tions [13]. It is now known that a large proportion of gene loci are polymorphic in most species [28], and that evolutionary genetic substitutions occur in the human line, for instance, at a rate of about 50 nucleotide changes per generation [20], [24], [25], [26]. The puzzling observation [21], [40], [46], that homologous proteins in different species evolve at nearly constant rates is very difficult to account for with classical evolutionary theory, and at the very least gives a solid indication that there are qualitative differences between the ways molecules evolve and the ways morphological structures evolve. -

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory Variations in Punctuated Equilibrium and and the Diffusion of Innovation

An Introduction to Punctuated Equilibrium: A Model for Understanding Stability and Dramatic Change in Public Policies January 2018 This briefing note belongs to a series on the Tobacco policies can serve as an example to various models used in political science to illustrate this idea. Up until 1965, this policy had represent public policy development processes. changed very little, whereas in the late 1960s and Each of these briefing notes begins by describing early 1970s a radical change occurred in the analytical framework proposed by the given response to the actions of certain stakeholders, model. With this model in mind, we then set out to such as the US Surgeon General's 1964 examine questions that public health actors might publication of the now-famous report entitled ask about public policies. Our aim in these notes Smoking and Health. is not to further refine existing models; nor is it to advocate for the adoption of one model in To incorporate their insight into public policy particular. Our purpose is rather to suggest how analysis, Baumgartner and Jones sought to each of these models constitutes a useful reconcile in an integrated model the long periods interpretive lens that can guide reflection and of equilibrium, already well explained by the action leading to the production of healthy public incrementalist model, and the abrupt policies. punctuations of political systems. This became known as the punctuated equilibrium model. The punctuated equilibrium model aims to explain why public policies tend to be characterized by long periods of stability punctuated by short periods of radical change. -

V Sem Zool Punctuated Equilibrium

V Sem Zool Punctuated Equilibrium Gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are two ways in which the evolution of a species can occur. A species can evolve by only one of these, or by both. Scientists think that species with a shorter evolution evolved mostly by punctuated equilibrium, and those with a longer evolution evolved mostly by gradualism. Both phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are speciation theory and are valid models for understanding macroevolution. Both theories describe the rates of speciation. For Gradualism, changes in species is slow and gradual, occurring in small periodic changes in the gene pool, whereas for Punctuated Equilibrium, evolution occurs in spurts of relatively rapid change with long periods of non-change. The gradualism model depicts evolution as a slow steady process in which organisms change and develop slowly over time. In contrast, the punctuated equilibrium model depicts evolution as long periods of no evolutionary change followed by rapid periods of change. Both are models for describing successive evolutionary changes due to the mechanisms of evolution in a time frame. Punctuated equilibrium The punctuated equilibrium hypothesis states that speciation events occur rapidly in geological time - over hundreds of thousands to millions of years and that little change occurs in the time between speciation events. In other words, change only happens under certain conditions, and it happens rapidly. Instead of a slow, continuous movement, evolution tends to be characterized by long periods of virtual standstill or equilibrium punctuated by episodes of very fast development of new forms. It was proposed by Eldridge and Gould to explain the gaps in the fossil record - the fact that the fossil record does not show smooth evolutionary transitions. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology. -

Springer A++ Viewer

PublisherInfo PublisherName : BioMed Central PublisherLocation : London PublisherImprintName : BioMed Central Stephen Jay Gould dies ArticleInfo ArticleID : 4486 ArticleDOI : 10.1186/gb-spotlight-20020522-01 ArticleCitationID : spotlight-20020522-01 ArticleSequenceNumber : 152 ArticleCategory : Research news ArticleFirstPage : 1 ArticleLastPage : 3 RegistrationDate : 2002–5–22 ArticleHistory : OnlineDate : 2002–5–22 ArticleCopyright : BioMed Central Ltd2002 ArticleGrants : ArticleContext : 130593311 Hal Cohen Email: [email protected] PHILADELPHIA - Stephen Jay Gould, paleontologist, evolutionary biologist and popular author, died of abdominal mesothelioma Monday in New York City. He was 60. A provocative and controversial thinker, Gould was a fierce public defender of evolution. He became a figurehead for paleontology by making difficult concepts more digestible for the public in forums such as The New York Times and The New York Review of Books. While in graduate school, Gould and fellow student Niles Eldredge disputed the theories of evolution, which held that changes in organisms only occurred gradually, over eons. In their theory, known as punctuated equilibrium, evolution proceeded in bursts, followed by long periods of stasis. Thirty years later after their theory was first developed, the debate still rages. Among the many awards and honors bestowed upon Gould were membership in the National Academy of Sciences, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He also served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Gould wrote more than a dozen books, most recently publishing the 1,454-page The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Harvard, 2001) and, this month, I Have Landed : The End of a Beginning in Natural History (Harmony Books, 2002). -

Punctuated Equilibrium Models in Organizational Decision Making 135

1 2 Punctuated Equilibrium Models 3 4 8 5 in Organizational Decision 6 7 Making 8 9 10 Scott E. Robinson 11 12 13 14 CONTENTS 15 16 8.1 Two Research Conundrums..................................................................................................134 17 8.1.1 Lindblom’s Theory of Administrative Incrementalism...........................................134 18 8.1.2 Wildavsky’s Theory of Budgetary Incrementalism.................................................135 19 8.1.3 The Diverse Meanings of Budgetary “Incrementalism”..........................................135 20 8.1.4 A Brief Aside on Paleontology.................................................................................136 21 8.2 Punctuated Equilibrium Theory—A Way Out of Both Conundrums.................................136 22 8.3 A Theoretical Model of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory....................................................137 23 8.4 Evidence of Punctuated Equilibria in Organizational Decision Making ............................139 24 8.4.1 Punctuated Equilibrium and the Federal Budget.....................................................139 25 8.4.2 Punctuated Equilibrium and Local Government Budgets.......................................140 26 8.4.3 Punctuated Equilibrium and the Federal Policy Process.........................................141 27 8.4.4 Punctuated Equilibrium and Organizational Bureaucratization ..............................142 28 8.4.5 Assessing the Evidence.............................................................................................143 -

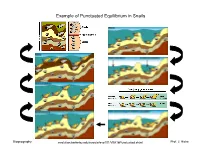

Example of Punctuated Equilibrium in Snails

Example of Punctuated Equilibrium in Snails Biogeography evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VIIA1bPunctuated.shtml1 Prof. J. Hicke Punctuated Equilibrium Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 2 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric Speciation http://wps.pearsoncustom.com/wps/media/objects/3014/3087289/Web_Tutorials/18_A01.swf Biogeography 3 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric Speciation: Vicariance Event Biogeography 4 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric speciation, founder event Genes rare in original population are dominant in founding population Biogeography 5 Prof. J. Hicke Sympatric and Parapatric Speciation sympatric: extensive overlap parapatric: minimal overlap (partial geographic separation) Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 6 Prof. J. Hicke Parapatric Speciation No extrinsic barrier to gene flow, but… 1. restricted gene flow within population 2. varying selective pressures across the population range “Although continuously distributed, different flowering times have begun to reduce gene flow between metal-tolerant plants and metal-intolerant plants. “ evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VC1dParapatric.shtml Biogeography 7 Prof. J. Hicke Example of Sympatric Speciation • 200 years ago, flies only on hawthorns • then, introduction of domestic apple • females lay eggs on type of fruit they grew up on; males look for mates on type of fruit they grew up on • restricted gene flow • speciation http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VC1eSympatric.shtml Biogeography 8 Prof. J. Hicke Example of Sympatric Speciation Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 9 Prof. J. Hicke Adaptive Radiation often rapid speciation: Lake Victoria: 100s of new species in <12,000 years Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 10 Prof. J. Hicke Adaptive Radiation www.micro.utexas.edu/courses/levin/bio304/evolution/speciation.html Biogeography 11 Prof. -

Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) All Sprouts Content Sprouts 4-1-2008 Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis Kalle Lyytinen Case Western Reserve University, [email protected] Mike Newman Agder University College Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all Recommended Citation Lyytinen, Kalle and Newman, Mike, " Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis" (2008). All Sprouts Content. 120. http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all/120 This material is brought to you by the Sprouts at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in All Sprouts Content by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Working Papers on Information Systems ISSN 1535-6078 Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis Kalle Lyytinen Case Western Reserve University, USA Mike Newman Agder University College, Norway Abstract We view information system development (ISD) and change as a socio-technical change process in which technologies, human actors, organizational relationships and tasks change. We outline a punctuated socio-technical change model that recognizes both incremental and dynamic and abrupt changes during ISD and change. The model identifies events that incrementally change the information system as well as punctuate its deep structure in its evolutionary path at multiple levels. The analysis of these event sequences helps explain how and why an ISD outcome emerged. -

Evolution in the Weak-Mutation Limit: Stasis Periods Punctuated by Fast Transitions Between Saddle Points on the Fitness Landscape

Evolution in the weak-mutation limit: Stasis periods punctuated by fast transitions between saddle points on the fitness landscape Yuri Bakhtina, Mikhail I. Katsnelsonb, Yuri I. Wolfc, and Eugene V. Kooninc,1 aCourant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, NY 10012; bInstitute for Molecules and Materials, Radboud University, NL-6525 AJ Nijmegen, The Netherlands; and cNational Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894 Contributed by Eugene V. Koonin, December 16, 2020 (sent for review July 24, 2020; reviewed by Sergey Gavrilets and Alexey S. Kondrashov) A mathematical analysis of the evolution of a large population occur (9, 10). The long intervals of stasis are punctuated by short under the weak-mutation limit shows that such a population periods of rapid evolution during which speciation occurs, and the would spend most of the time in stasis in the vicinity of saddle previous dominant species is replaced by a new one. Gould and points on the fitness landscape. The periods of stasis are punctu- Eldredge emphasized that PE was not equivalent to the “hopeful ated by fast transitions, in lnNe/s time (Ne, effective population monsters” idea, in that no macromutation or saltation was proposed size; s, selection coefficient of a mutation), when a new beneficial to occur, but rather a major acceleration of evolution via rapid mutation is fixed in the evolving population, which accordingly succession of “regular” mutations that resulted in the appearance of moves to a different saddle, or on much rarer occasions from a instantaneous speciation, on a geological scale. -

Punctuated Equilibrium Vs. Phyletic Gradualism

International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology Vol. 3, No. 4, December, 2011 Punctuated Equilibrium vs. Phyletic Gradualism Monalie C. Saylo1, Cheryl C. Escoton1 and Micah M. Saylo2 1 University of Antique, Sibalom, Antique, Philippines 2 DepEd Sibalom North District, Sibalom, Antique, Philippines [email protected] Abstract Both phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are speciation theory and are valid models for understanding macroevolution. Both theories describe the rates of speciation. For Gradualism, changes in species is slow and gradual, occurring in small periodic changes in the gene pool, whereas for Punctuated Equilibrium, evolution occurs in spurts of relatively rapid change with long periods of non-change. The gradualism model depicts evolution as a slow steady process in which organisms change and develop slowly over time. In contrast, the punctuated equilibrium model depicts evolution as long periods of no evolutionary change followed by rapid periods of change. Both are models for describing successive evolutionary changes due to the mechanisms of evolution in a time frame. Keywords: macroevolution, phyletic gradualism, punctuated equilibrium, speciation, evolutionary change 1. Introduction Has the evolution of life proceeded as a gradual stepwise process, or through relatively long periods of stasis punctuated by short periods of rapid evolution? To date, what is clear is that both evolutionary patterns – phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium have played at least some role in the evolution of life. Gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are two ways in which the evolution of a species can occur. A species can evolve by only one of these, or by both. Scientists think that species with a shorter evolution evolved mostly by punctuated equilibrium, and those with a longer evolution evolved mostly by gradualism.