A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

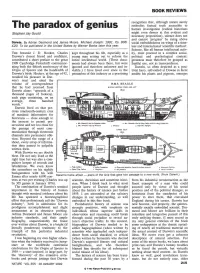

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

Richard Dawkins

RICHARD DAWKINS HOW A SCIENTIST CHANGED THE WAY WE THINK Reflections by scientists, writers, and philosophers Edited by ALAN GRAFEN AND MARK RIDLEY 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 2006 with the exception of To Rise Above © Marek Kohn 2006 and Every Indication of Inadvertent Solicitude © Philip Pullman 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should -

The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint and Speciation

The spindle assembly checkpoint and speciation Robert C. Jackson1 and Hitesh B. Mistry2 1 Pharmacometrics Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom 2 Division of Pharmacy, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom ABSTRACT A mechanism is proposed by which speciation may occur without the need to postulate geographical isolation of the diverging populations. Closely related species that occupy overlapping or adjacent ecological niches often have an almost identical genome but differ by chromosomal rearrangements that result in reproductive isolation. The mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint normally functions to prevent gametes with non-identical karyotypes from forming viable zygotes. Unless gametes from two individuals happen to undergo the same chromosomal rearrangement at the same place and time, a most improbable situation, there has been no satisfactory explanation of how such rearrange- ments can propagate. Consideration of the dynamics of the spindle assembly checkpoint suggest that chromosomal fission or fusion events may occur that allow formation of viable heterozygotes between the rearranged and parental karyotypes, albeit with decreased fertility. Evolutionary dynamics calculations suggest that if the resulting heterozygous organisms have a selective advantage in an adjoining or overlapping ecological niche from that of the parental strain, despite the reproductive disadvantage of the population carrying the altered karyotype, it may accumulate sufficiently that homozygotes begin to emerge. At this point the reproductive disadvantage of the rearranged karyotype disappears, and a single population has been replaced by two populations that are partially reproductively isolated. This definition of species as populations that differ from other, closely related, species by karyotypic changes is consistent with the classical definition of a species as a population that is capable of interbreeding to produce fertile progeny. -

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution a Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused by Dr

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution A Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused By Dr. Mike Webster, Dept. of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University ([email protected]); February 2010 The current debate over evolution and “intelligent design” (ID) is being driven by a relatively small group of individuals who object to the theory of evolution for religious reasons. The debate is fueled, though, by misunderstandings on the part of the American public about what evolutionary biology is and what it says. These misunderstandings are exploited by proponents of ID, intentionally or not, and are often echoed in the media. In this booklet I briefly outline and explain 10 of the most common (and serious) misunderstandings. It is impossible to treat each point thoroughly in this limited space; I encourage you to read further on these topics and also by visiting the websites given on the resource sheet. In addition, I am happy to send a somewhat expanded version of this booklet to anybody who is interested – just send me an email to ask for one! What are the misunderstandings? 1. Evolution is progressive improvement of species Evolution, particularly human evolution, is often pictured in textbooks as a string of organisms marching in single file from “simple” organisms (usually a single celled organism or a monkey) on one side of the page and advancing to “complex” organisms on the opposite side of the page (almost invariably a human being). We have all seen this enduring image and likely have some version of it burned into our brains. -

The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins Is Another

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT ooks about science tend to fall into two categories: those that explain it to lay people in the hope of cultivat- Bing a wide readership, and those that try to persuade fellow scientists to support a new theory, usually with equations. Books that achieve both — changing science and reach- ing the public — are rare. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) was one. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins is another. From the moment of its publication 40 years ago, it has been a sparkling best-seller and a TERRY SMITH/THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY SMITH/THE LIFE IMAGES TERRY scientific game-changer. The gene-centred view of evolution that Dawkins championed and crystallized is now central both to evolutionary theoriz- ing and to lay commentaries on natural history such as wildlife documentaries. A bird or a bee risks its life and health to bring its offspring into the world not to help itself, and certainly not to help its species — the prevailing, lazy thinking of the 1960s, even among luminaries of evolution such as Julian Huxley and Konrad Lorenz — but (uncon- sciously) so that its genes go on. Genes that cause birds and bees to breed survive at the expense of other genes. No other explana- tion makes sense, although some insist that there are other ways to tell the story (see K. Laland et al. Nature 514, 161–164; 2014). What stood out was Dawkins’s radical insistence that the digital information in a gene is effectively immortal and must be the primary unit of selection. -

The God Delusion: a Worldview Analysis Bill Martin Cornerstone Church of Lakewood Ranch - August 6, 2008

The God Delusion: A Worldview Analysis Bill Martin Cornerstone Church of Lakewood Ranch - August 6, 2008 Richard Dawkins, Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University “The God Delusion really marked the point where Dawkins transformed from the professor holding the Charles Simonyi Chair for the Public Understanding of Science to the celebrity fundamentalist atheist.” - Carl Packman, “An Evangelical Atheist” in New Statesman, 8.5.08 The Selfish Gene, Oxford University Press, 1976 The Extended Phenotype, Oxford University Press, 1982 The Blind Watchmaker, W. W. Norton & Company, 1986 River out of Eden, Basic Books, 1995 Climbing Mount Improbable, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996 Unweaving the Rainbow, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998 A Devil's Chaplain, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003 The Ancestor's Tale, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004 The God Delusion, Bantam Books, 2006 / Bill’s edition: Mariner Books; 1 edition (January 16, 2008) Ad hominem - attacking an opponent's character rather than answering his argument Outline of Bill’s Talking Points 1. General Summary 2. Two Worldview Presuppositions 3. Personal Reflections and Lessons Resources: Books and Journals Aikman, David. The Delusion of Disbelief. Nashville: Tyndale House, 2008. McGrath, Alister. The Dawkins Delusion? Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2007. _______. Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. Ganssle, Gregory E. “Dawkins’s Best Argument: The Case against God in The God Delusion,” Philosophia Christi , 2008,Volume 10, Number 1, pp. 39-56. Plantinga, Alvin. “The Dawkins Confusion,” Books & Culture, March/April 2007, Vol. 13, No. 2, Page 21. The Duomo Pieta (Florence, Italy) Reviews of The God Delusion “dogmatic, rambling and self-contradictory” - Andrew Brown in Prospect “he risks destroying a larger target”- Jim Holt in The New York Times “I'm forced, after reading his new book, to conclude he's actually more an amateur.” - H. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology. -

Islands of Order

Islands of Order J. Stephen Lansing Professor, Asian School of the Environment, and Director, Complexity Institute Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Not long ago, both ecology and social science were organized around ideas of stability. This view has changed in ecology, where nonlinear change is increasingly seen as normal, but not (yet) in social science. This talk describes two surprising discoveries about emergent cultural patterns in traditional Indonesian societies. The first story is about the emergence of cooperation in Bali. Along a typical Balinese river, small groups of farmers meet regularly in water temples to manage their irrigation systems. They have done so for a thousand years. Over the centuries, water temple networks have expanded to manage the ecology of rice terraces at the scale of whole watersheds. Although each group focuses on its own problems, a global solution nonetheless emerges that optimizes irrigation flows for everyone. Did someone have to design Bali's water temple networks, or could they have emerged from a self-organizing process? The second story is about language. In 1995 Richard Dawkins memorably described genes as a "River out of Eden", an unbroken connection between the first DNA molecules and every living organism. We are not accustomed to think of language in the same way. But we each speak a language that has been transmitted to us in an unbroken chain stretching back to the origin, not of life, but of our species. “Language moves down time in a current of its own making,” as Edward Sapir wrote in 1921. In a study of 982 tribesmen from 25 villages on the islands of Timor and Sumba, we use genetic information to seek patterns in the flow of 17 languages since the Pleistocene. -

Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(S): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S

Paleontological Society Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(s): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba Reviewed work(s): Source: Paleobiology, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 4-15 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400563 . Accessed: 27/08/2012 17:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Paleobiology. http://www.jstor.org Paleobiology,8(1), 1982, pp. 4-15 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form StephenJay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba* Abstract.-Adaptationhas been definedand recognizedby two differentcriteria: historical genesis (fea- turesbuilt by naturalselection for their present role) and currentutility (features now enhancingfitness no matterhow theyarose). Biologistshave oftenfailed to recognizethe potentialconfusion between these differentdefinitions because we have tendedto view naturalselection as so dominantamong evolutionary mechanismsthat historical process and currentproduct become one. Yet if manyfeatures of organisms are non-adapted,but available foruseful cooptation in descendants,then an importantconcept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generallyremain unconsidered):features that now enhance fitnessbut were not built by naturalselection for their current role. -

Darwin's Middle Road∗

Stephen Jay Gould DARWIN'S MIDDLE ROAD∗ "We began to sail up the narrow strait lamenting," narrates Odysseus. "For on the one hand lay Scylla, with twelve feet all dangling down; and six necks exceeding long, and on each a hideous head, and therein three rows of teeth set thick and close, full of black death. And on the other mighty Charybdis sucked down the salt sea water. As often as she belched it forth, like a cauldron on a great fire she would seethe up through all her troubled deeps." Odysseus managed to swerve around Charybdis, but Scylla grabbed six of his finest men and devoured them in his sight-"the most pitiful thing mine eyes have seen of all my travail in searching out the paths of the sea." False lures and dangers often come in pairs in our legends and metaphors—consider the frying pan and the fire, or the devil and the deep blue sea. Prescriptions for avoidance either emphasize a dogged steadiness—the straight and narrow of Christian evangelists—or an averaging between unpleasant alternatives—the golden mean of Aristotle. The idea1 of steering a course between undesirable extremes emerges as a central prescription for a sensible life. The nature of scientific creativity is both a perennial topic of discussion and a prime candidate for seeking a golden mean. The two extreme positions have not been directly competing for allegiance of the unwary. They have, rather, replaced each other sequentially, with one now in the ascendancy, the other eclipsed. The first—inductivism—held that great scientists are primarily great observers and patient accumulators of information. -

'Problem of Evil' in the Context of The

The ‘Problem of Evil’ in the Context of the French Enlightenment: Bayle, Leibniz, Voltaire, de Sade “The very masterpiece of philosophy would be to develop the means Providence employs to arrive at the ends she designs for man, and from this construction to deduce some rules of conduct acquainting this wretched two‐footed individual with the manner wherein he must proceed along life’s thorny way, forewarned of the strange caprices of that fatality they denominate by twenty different titles, and all unavailingly, for it has not yet been scanned nor defined.” ‐Marquis de Sade, Justine, or Good Conduct Well Chastised (1791) “The fact that the world contains neither justice nor meaning threatens our ability both to act in the world and to understand it. The demand that the world be intelligible is a demand of practical and of theoretical reason, the ground of thought that philosophy is called to provide. The question of whether [the problem of evil] is an ethical or metaphysical problem is as unimportant as it is undecidable, for in some moments it’s hard to view as a philosophical problem at all. Stated with the right degree of generality, it is but unhappy description: this is our world. If that isn’t even a question, no wonder philosophy has been unable to give it an answer. Yet for most of its history, philosophy has been moved to try, and its repeated attempts to formulate the problem of evil are as important as its attempts to respond to it.” ‐Susan Neiman, Evil in Modern Thought – An Alternative History of Philosophy (2002) Claudine Lhost (Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy with Honours) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia in 2012 1 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. -

Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt229036tr No online items Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives August 2011 ; revised 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould M1437 1 Papers M1437 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stephen Jay Gould papers creator: Gould, Stephen Jay source: Shearer, Rhonda Roland Identifier/Call Number: M1437 Physical Description: 575 Linear Feet(958 boxes) Physical Description: 1180 computer file(s)(52 megabytes) Date (inclusive): 1868-2004 Date (bulk): bulk Abstract: This collection documents the life of noted American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, Stephen Jay Gould. The papers include correspondence, juvenilia, manuscripts, subject files, teaching files, photographs, audiovisual materials, and personal and biographical materials created and compiled by Gould. Both textual and born-digital materials are represented in the collection. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Stephen Jay Gould Papers, M1437. Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Publication Rights While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use