Modern Nonfiction Reading Selection by Stephen Jay Gould Sex, Drugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution a Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused by Dr

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution A Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused By Dr. Mike Webster, Dept. of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University ([email protected]); February 2010 The current debate over evolution and “intelligent design” (ID) is being driven by a relatively small group of individuals who object to the theory of evolution for religious reasons. The debate is fueled, though, by misunderstandings on the part of the American public about what evolutionary biology is and what it says. These misunderstandings are exploited by proponents of ID, intentionally or not, and are often echoed in the media. In this booklet I briefly outline and explain 10 of the most common (and serious) misunderstandings. It is impossible to treat each point thoroughly in this limited space; I encourage you to read further on these topics and also by visiting the websites given on the resource sheet. In addition, I am happy to send a somewhat expanded version of this booklet to anybody who is interested – just send me an email to ask for one! What are the misunderstandings? 1. Evolution is progressive improvement of species Evolution, particularly human evolution, is often pictured in textbooks as a string of organisms marching in single file from “simple” organisms (usually a single celled organism or a monkey) on one side of the page and advancing to “complex” organisms on the opposite side of the page (almost invariably a human being). We have all seen this enduring image and likely have some version of it burned into our brains. -

Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt229036tr No online items Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives August 2011 ; revised 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould M1437 1 Papers M1437 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stephen Jay Gould papers creator: Gould, Stephen Jay source: Shearer, Rhonda Roland Identifier/Call Number: M1437 Physical Description: 575 Linear Feet(958 boxes) Physical Description: 1180 computer file(s)(52 megabytes) Date (inclusive): 1868-2004 Date (bulk): bulk Abstract: This collection documents the life of noted American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, Stephen Jay Gould. The papers include correspondence, juvenilia, manuscripts, subject files, teaching files, photographs, audiovisual materials, and personal and biographical materials created and compiled by Gould. Both textual and born-digital materials are represented in the collection. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Stephen Jay Gould Papers, M1437. Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Publication Rights While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use -

History of Genetics Book Collection Catalogue

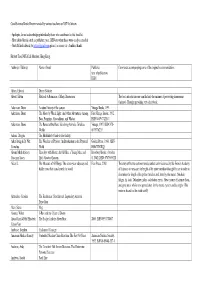

History of Genetics Book Collection Catalogue Below is a list of the History of Genetics Book Collection held at the John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK. For all enquires please contact Mike Ambrose [email protected] +44(0)1603 450630 Collection List Symposium der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Hygiene und Mikrobiologie Stuttgart Gustav Fischer 1978 A69516944 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 5th international congress on tropical agriculture 28-31 July 1930 Brussels Imprimerie Industrielle et Finangiere 1930 A6645004483 œ.00 30/3/1994 7th International Chromosome Conference Oxford Oxford 1980 A32887511 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 20/2/1991 7th International Chromosome Conference Oxford Oxford 1980 A44688257 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 26/6/1992 17th international agricultural congress 1937 1937 A6646004482 œ.00 30/3/1994 19th century science a selection of original texts 155111165910402 œ14.95 13/2/2001 150 years of the State Nikitsky Botanical Garden bollection of scientific papers. vol.37 Moscow "Kolos" 1964 A41781244 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 Haldane John Burdon Sanderson 1892-1964 A banned broadcast and other essays London Chatto and Windus 1946 A10697655 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 Matsuura Hajime A bibliographical monograph on plant genetics (genic analysis) 1900-1929 Sapporo Hokkaido Imperial University 1933 A47059786 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 Hoppe Alfred John A bibliography of the writings of Samuel Butler (author of "erewhon") and of writings about him with some letters from Samuel Butler to the Rev. F. G. Fleay, now first published London The Bookman's Journal -

A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 61 Issue 5 Issue 5 - October 2008 Article 1 10-2008 A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution Scott Dodson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Scott Dodson, A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution, 61 Vanderbilt Law Review 1319 (2008) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol61/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 61 OCTOBER 2008 NUMBER 5 A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution Scott Dodson* I. INTRODU CTION ................................................................... 1320 II. THE METAPHOR OF A "LIVING" CONSTITUTION .................. 1322 III. EVALUATING THE METAPHOR ............................................. 1325 A. MetaphoricalAccuracies and Gaps ........................ 1326 B. ConstitutionalEvolution? ....................................... 1327 1. By Natural Selection ................................... 1329 2. O ther O ptions .............................................. 1333 a. Artificial Selection ............................ 1333 b. Intelligent Design ............................. 1335 c. Hybridization.................................... 1337 IV. EXTENDING THE METAPHOR .............................................. -

Eight Little Piggies

Eight Little Piggies ELP 1. Unenchanted Evening ............................................................................................ 1 ELP 2. The Golden Rule: A Proper Scale for Our Environmental Crisis ........................... 3 ELP 3. Losing a Limpet ...................................................................................................... 5 ELP 4. Eight Little Piggies ................................................................................................ 5 ELP 5. Bent Out of Shape ................................................................................................... 7 ELP 6. An Earful of Jaw ..................................................................................................... 8 ELP 7. Full of Hot Air ...................................................................................................... 10 ELP 8: Men of the Thirty-Third Division: An Essay on Integrity .................................... 11 ELP 9. Darwin and Paley Meet the Invisible Hand .......................................................... 12 ELP 10. More Light on Leaves ......................................................................................... 14 ELP 11. On Rereading Edmund Halley ............................................................................ 15 ELP 12. Fall in the House of Ussher................................................................................. 16 ELP 13. Muller Bros. Moving & Storage ........................................................................ -

Ever Since Darwin

Ever Since Darwin ESD 1. Darwin’s Delay....................................................................................................... 1 ESD 2. Darwin’s Sea Change, or Five Years at the Captain’s Table ................................. 3 ESD 3. Darwin’s Dilemma: The Odyssey of Evolution ..................................................... 3 ESD 4. Darwin’s Untimely Burial ...................................................................................... 4 ESD 5. A Matter of Degree................................................................................................. 6 ESD 6. Bushes and Ladders in Human Evolution .............................................................. 7 ESD 7. The Child as Man’s Real Father ............................................................................. 9 ESD 8. Human Babies as Embryos................................................................................... 10 ESD 9. The Misnamed, Mistreated, and Misunderstood Irish Elk ................................... 11 ESD 10. Organic Wisdom, or Why Should a Fly Eat Its Mother from Inside ................. 13 ESD 11. Of Bamboos, Cicadas, and the Economy of Adam Smith ................................. 14 ESD 12. The Problem of Perfection ................................................................................. 15 ESD 13. The Pentagon of Life .......................................................................................... 16 ESD 14. An Unsung Single-Celled Hero ......................................................................... -

Cumulative Index

Stephen Jay Gould’s Essays on Natural History: A Cumulative Index Hyperlinks A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A Word of Introduction. This large file comines the indeces of all ten volumes of Stephen Jay Gould’s collections of essays reprinted from Natural History magazine. The goal is to reduce the effort to locate the reference to a particular person, item, or event; and similarly, to allow the reader to find all references to (say) Luis Alvarez in all volumes in one place. The row of hyperlinks will take you directly to the beginning of each letter’s section. To see this list at all times, click on the “bookmarks” icon in Adobe (found on the upper left of the screen). The file itself is also searchable, so you may seek the key word of your interest directly. As with all of these tasks, the identifying nomenclature is given as three or four letters followed by a number. The letters identify the volume; ESD refers to “Ever Since Darwin,” for example. (The entire sequence is listed below, in chronological order.) Similarly, the number refers to the order in which the essay appears in that volume, following Gould’s own numbering scheme. For ease of identification, I include the essay’s title as well. ESD: Ever Since Darwin. TPT: The Panda’s Thumb. HTHT: Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes. TFS: The Flamingo’s Smile. BFB: Bully for Brontosaurus. ELP: Eight Little Piggies. -

Good Science Books Recommended by Various Teachers on NSTA's Listserv

Good Science Books Recommended by various teachers on NSTA’s listserv - Apologies for not acknowledging individually those who contributed to this book list. - Have added details such as publisher, year, ISBN etc when these were easily accessible - Grateful for feedback (to [email protected] please) re errors etc. A million thanks. Herbert Tsoi, NSTA Life Member, Hong Kong. Author(s) / Editor(s) Name of book Publisher, Comments accompanying some of the original recommendations year of publication, ISBN Abbey, Edward Desert Solitaire Abbott, Edwin Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions The best introduction one can find into the manner of perceiving dimensions (Asimov). Thought provoking very short book. Ackerman, Diane A natural history of the senses Vintage Books, 1991. Ackerman, Diane The Moon by Whale Light: And Other Adventures Among First Vintage Books, 1992. Bats, Penguins, Crocodilians, and Whales ISBN 0-679-74226-3 Ackerman, Diane The Rarest of the Rare: Vanishing Animals, Timeless Vintage, 1997. ISBN 978- Worlds 0679776239 Adams, Douglas The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Adler, Irving & De Witt, The Wonders of Physics: An Introduction to the Physical Golden Press, 1966. ASIN Cornelius World B0007DVHGQ Albom, Mitch & Stacy Tuesdays with Morrie: An Old Man, a Young Man, and Broadway Books; (October Creamer, Stacy Life's Greatest Lesson. 8, 2002) ISBN: 076790592X Alder, K. The Measure of All Things: The seven-year odyssey and Free Press, 2002. The story of the two astronomers/scientists commissioned by the French Academy hidden error that transformed the world of Sciences to measure the length of the prime meridian through France in order to determine the length of the prime meridian and, thereby, the meter. -

Title and Contents

Two Historical Investigations in Evolutionary Biology A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Max W. Dresow IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Dr. Emilie C. Snell-Rood October 2015 © Max Walter Dresow. 2015 Table of Contents The history of form and the forms of history: Stephen Jay Gould between D’Arcy Thompson and Charles Darwin…………………………………… 1 The problem of beginnings: “Mivart’s dilemma” and the direction of 19th century evolutionary studies.………………………………………………….65 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………144 1. The history of form and the forms of history: Stephen Jay Gould between D’Arcy Thompson and Charles Darwin Max W. Dresow “Our greatest intellectual adventures often occur within ourselves—not in the restless search for new facts and new objects on the earth or in the stars, but from a need to expunge old prejudices and build new conceptual structures. No hunt can promise a sweeter reward, a more admirable goal, than the excitement of thoroughly revised understanding—the inward journey that thrills real scholars and scares the bejesus us out of the rest of us” (Gould 2001, p. 355). “Steve…was first and always a morphologist and developmentalist” (Eldredge 2013, p. 6). Introduction: Stephen Jay Gould and the science of form The story of Stephen Jay Gould’s evolutionary philosophy has yet to be fully told, because I suspect it cannot be fully told. For one thing, there is no univocal philosophy to which Gould’s name attaches (Ruse 1996, pp. 494-507, Thomas 2009). His views changed as he aged, not as a scaling-up of ancestral potentialities, but rather as a series of heterochronies involving both translocations and deletions. -

WONDERFUL LIFE the Burgess Shale and Lhe Nature of Hislory

BY STEPHEN JAY GOULD IN NORTON PAPERBACK EVER SINCE DARWIN Reflections in Natural Hislory THE PANDA'S THUMB More Reflections in Natural History THE MISMEASURE OF MAN HEN'S TEETH AND HORSE'S TOES Furlher ReflectUms in Natural Hislory THE FLAMINGO'S SMILE Reflections in Natural History AN URCHIN IN THE STORM Essays about Books and Ideas ILLUMINATIONS A Besliary (with R. W. Purcell) WONDERFUL LIFE The Burgess Shale and lhe Nature of Hislory BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS Reflections in Natural Hislory FINDERS, KEEPERS Treasures and Oddities of Natural Hislory Collectors from Peter the Great to Louis Agassiz (with R. W. Purcell) Wonderful Life w . W . NORTON & COMPANY' NEW YORK· LONDON Wonderful Life The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History STEPHEN JAY GOULD Copyright C 19!!9 by St<.pl<~l Jay Could All rights rt'SCl\l.'<I. Prink-<i in the Unik-<i Slilt~ of America. The text of this boobs composed in 10 Ih/ 13 Avanta, with display type set in Fenice Light. Composition and manufacturing by The Haddon Craftsmen, Inc. Book design by Antonina Krass. "Design" copyright 1936 by Robert Frost and renewed 1964 by Lesley Frost Ballantine. Reprinted from The Poetry of Robert Frost, edited by Edward Connery Lathem, by permission of Henry Holt and Company, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging· in· Publication Data Could, Stephen Jay. Wonderful life: the Burgess Shale and the nature of history / Stephen Jay Could. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Evolution-History. 2. Invertebrates, Fossil. 3. Paleontology-Cambrian. 4. Paleontology-British CoIumbia-Yoho National Park. 5. Burgess Shale. -

The Exemplary Kuhnian: Gould’S Structure Revisited

The Exemplary Kuhnian: Gould’s Structure Revisited BY GREGORY RADICK* STEPHEN JAY GOULD. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2002. xxiv + 1433 pp., illus., index. ISBN: 0-674-00613- 5. $39.95 (hardcover). The Origin of Species recognized no goal set either by God or nature. Even such marvelously adapted organs as the eye and hand of man—organs whose design had previously provided powerful arguments for the existence of a su- preme artificer and an advance plan—were products of a process that moved steadily from primitive beginnings but toward no goal. Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962)1 Darwin reveled in this unusual feature of his theory—this mechanism for im- mediate fit alone, with no rationale for increments of general progress or com- plexification. The vaunted progress of life is really random motion away from simple beginnings, not directed impetus toward inherently advantageous complexity. Stephen Jay Gould, Life’s Grandeur (1996)2 The echo in Stephen Jay Gould’s way of expressing the contrast between goal-directed progress and Darwinian progress—for Thomas Kuhn, the very model of scientific advance—may or may not have been deliberate. Certainly Gould was candid about his debt to The Structure of Scientific Revolutions * Centre for History and Philosophy of Science, Department of Philosophy, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; [email protected]. The following abbreviations are used: SET, Stephen Jay Gould, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory; SSR, Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 1. Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed.