1 Wonderful Life Revisited: Chance and Contingency in the Ediacaran-Cambrian Radiation Douglas H. Erwin Department of Paleobiolo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

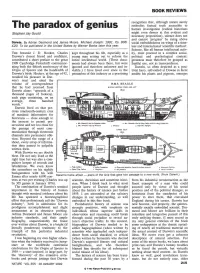

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

Early Sponge Evolution: a Review and Phylogenetic Framework

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Palaeoworld 27 (2018) 1–29 Review Early sponge evolution: A review and phylogenetic framework a,b,∗ a Joseph P. Botting , Lucy A. Muir a Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 39 East Beijing Road, Nanjing 210008, China b Department of Natural Sciences, Amgueddfa Cymru — National Museum Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3LP, UK Received 27 January 2017; received in revised form 12 May 2017; accepted 5 July 2017 Available online 13 July 2017 Abstract Sponges are one of the critical groups in understanding the early evolution of animals. Traditional views of these relationships are currently being challenged by molecular data, but the debate has so far made little use of recent palaeontological advances that provide an independent perspective on deep sponge evolution. This review summarises the available information, particularly where the fossil record reveals extinct character combinations that directly impinge on our understanding of high-level relationships and evolutionary origins. An evolutionary outline is proposed that includes the major early fossil groups, combining the fossil record with molecular phylogenetics. The key points are as follows. (1) Crown-group sponge classes are difficult to recognise in the fossil record, with the exception of demosponges, the origins of which are now becoming clear. (2) Hexactine spicules were present in the stem lineages of Hexactinellida, Demospongiae, Silicea and probably also Calcarea and Porifera; this spicule type is not diagnostic of hexactinellids in the fossil record. (3) Reticulosans form the stem lineage of Silicea, and probably also Porifera. (4) At least some early-branching groups possessed biminerallic spicules of silica (with axial filament) combined with an outer layer of calcite secreted within an organic sheath. -

Skeletonized Microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian Transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, Northern Spain

Skeletonized microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain SÉBASTIEN CLAUSEN and J. JAVIER ÁLVARO Clausen, S. and Álvaro, J.J. 2006. Skeletonized microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (2): 223–238. Two different assemblages of skeletonized microfossils are recorded in bioclastic shoals that cross the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary in the Esla nappe, Cantabrian Mountains. The uppermost Lower Cambrian sedimentary rocks repre− sent a ramp with ooid−bioclastic shoals that allowed development of protected archaeocyathan−microbial reefs. The shoals yield abundant debris of tube−shelled microfossils, such as hyoliths and hyolithelminths (Torellella), and trilobites. The overlying erosive unconformity marks the disappearance of archaeocyaths and the Iberian Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary. A different assemblage occurs in the overlying glauconitic limestone associated with development of widespread low−relief bioclastic shoals. Their lowermost part is rich in hyoliths, hexactinellid, and heteractinid sponge spicules (Eiffelia), chancelloriid sclerites (at least six form species of Allonnia, Archiasterella, and Chancelloria), cambroclaves (Parazhijinites), probable eoconchariids (Cantabria labyrinthica gen. et sp. nov.), sclerites of uncertain af− finity (Holoplicatella margarita gen. et sp. nov.), echinoderm ossicles and trilobites. Although both bioclastic shoal com− plexes represent similar high−energy conditions, the unconformity at the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary marks a drastic replacement of microfossil assemblages. This change may represent a real community replacement from hyolithelminth−phosphatic tubular shells to CES (chancelloriid−echinoderm−sponge) meadows. This replacement coin− cides with the immigration event based on trilobites previously reported across the boundary, although the partial infor− mation available from originally carbonate skeletons is also affected by taphonomic bias. -

Curious Creatures Using Fossil and Modern Evidence to Work out the Lifestyles of Extinct Animals

Earthlearningidea http://www.earthlearningidea.com Curious creatures Using fossil and modern evidence to work out the lifestyles of extinct animals Try comparing the features of animals today with • Of what animal(s) alive today does it remind you? those of fossils - can you predict the lifestyles of the • How did the animal move? (swim, crawl, float, extinct animals? wriggle, hop). • How did it catch its food? (predators often have Divide the pupils into groups. Give each group a copy grasping limbs for catching prey. Not all animals of the diagrams of animals shown below and a copy are herbivores or carnivores; some are filter of the reconstruction of life on page 3. Tell the pupils feeders (like mussels) or deposit feeders (like that all of these creatures lived in the sea about 515 worms). million years ago before there were any plants or • Could it see? (predators often have large eyes for animals on land. hunting). (Further background information is given for teachers • Is there evidence of other organs that could sense on page 2). the environment around? (feelers). • Look at the diagram on page 3. Where do you For each of the five animals shown in the diagram, think it lived? (swimming around, on the seabed, ask the pupils to answer the following questions and burrowing, on another animal or plant). to list the evidence they have used:- • Can you deduce anything else about the lifestyles of these five animals? Images reproduced with kind permission of The Burgess Shale Geoscience Foundation http://www.burgess-shale.bc.ca ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. The back up: Title: Curious creatures Time needed to complete activity: 20 minutes Subtitle: Using fossil and modern evidence to work Pupil learning outcomes: Pupils can: out the lifestyles of extinct animals • relate characteristics of marine animals today to similar characteristics shown by fossil evidence Topic: A snapshot of the history of life on Earth from long-extinct creatures; • realise that there are no right answers to this Age range of pupils: 10 - 18 years activity. -

The Cambrian Explosion: a Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals

The Cambrian Explosion A Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals Very suddenly, and at about the same horizon the world over, life showed up in the rocks with a bang. For most of Earth’s early history, there simply was no fossil record. Only recently have we come to discover otherwise: Life is virtually as old as the planet itself, and even the most ancient sedimentary rocks have yielded fossilized remains of primitive forms of life. NILES ELDREDGE, LIFE PULSE, EPISODES FROM THE STORY OF THE FOSSIL RECORD The Cambrian Explosion: A Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals Our home planet coalesced into a sphere about four-and-a-half-billion years ago, acquired water and carbon about four billion years ago, and less than a billion years later, according to microscopic fossils, organic cells began to show up in that inert matter. Single-celled life had begun. Single cells dominated life on the planet for billions of years before multicellular animals appeared. Fossils from 635,000 million years ago reveal fats that today are only produced by sponges. These biomarkers may be the earliest evidence of multi-cellular animals. Soon after we can see the shadowy impressions of more complex fans and jellies and things with no names that show that animal life was in an experimental phase (called the Ediacran period). Then suddenly, in the relatively short span of about twenty million years (given the usual pace of geologic time), life exploded in a radiation of abundance and diversity that contained the body plans of almost all the animals we know today. -

The Origin and Evolution of Arthropods Graham E

INSIGHT REVIEW NATURE|Vol 457|12 February 2009|doi:10.1038/nature07890 The origin and evolution of arthropods Graham E. Budd1 & Maximilian J. Telford2 The past two decades have witnessed profound changes in our understanding of the evolution of arthropods. Many of these insights derive from the adoption of molecular methods by systematists and developmental biologists, prompting a radical reordering of the relationships among extant arthropod classes and their closest non-arthropod relatives, and shedding light on the developmental basis for the origins of key characteristics. A complementary source of data is the discovery of fossils from several spectacular Cambrian faunas. These fossils form well-characterized groupings, making the broad pattern of Cambrian arthropod systematics increasingly consensual. The arthropods are one of the most familiar and ubiquitous of all ani- Arthropods are monophyletic mal groups. They have far more species than any other phylum, yet Arthropods encompass a great diversity of animal taxa known from the living species are merely the surviving branches of a much greater the Cambrian to the present day. The four living groups — myriapods, diversity of extinct forms. One group of crustacean arthropods, the chelicerates, insects and crustaceans — are known collectively as the barnacles, was studied extensively by Charles Darwin. But the origins Euarthropoda. They are united by a set of distinctive features, most and the evolution of arthropods in general, embedded in what is now notably the clear segmentation of their bodies, a sclerotized cuticle and known as the Cambrian explosion, were a source of considerable con- jointed appendages. Even so, their great diversity has led to consider- cern to him, and he devoted a substantial and anxious section of On able debate over whether they had single (monophyletic) or multiple the Origin of Species1 to discussing this subject: “For instance, I cannot (polyphyletic) origins from a soft-bodied, legless ancestor. -

Fossils from South China Redefine the Ancestral Euarthropod Body Plan Cédric Aria1 , Fangchen Zhao1, Han Zeng1, Jin Guo2 and Maoyan Zhu1,3*

Aria et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2020) 20:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1560-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Fossils from South China redefine the ancestral euarthropod body plan Cédric Aria1 , Fangchen Zhao1, Han Zeng1, Jin Guo2 and Maoyan Zhu1,3* Abstract Background: Early Cambrian Lagerstätten from China have greatly enriched our perspective on the early evolution of animals, particularly arthropods. However, recent studies have shown that many of these early fossil arthropods were more derived than previously thought, casting uncertainty on the ancestral euarthropod body plan. In addition, evidence from fossilized neural tissues conflicts with external morphology, in particular regarding the homology of the frontalmost appendage. Results: Here we redescribe the multisegmented megacheirans Fortiforceps and Jianfengia and describe Sklerolibyon maomima gen. et sp. nov., which we place in Jianfengiidae, fam. nov. (in Megacheira, emended). We find that jianfengiids show high morphological diversity among megacheirans, both in trunk ornamentation and head anatomy, which encompasses from 2 to 4 post-frontal appendage pairs. These taxa are also characterized by elongate podomeres likely forming seven-segmented endopods, which were misinterpreted in their original descriptions. Plesiomorphic traits also clarify their connection with more ancestral taxa. The structure and position of the “great appendages” relative to likely sensory antero-medial protrusions, as well as the presence of optic peduncles and sclerites, point to an overall -

Geobiological Events in the Ediacaran Period

Geobiological Events in the Ediacaran Period Shuhai Xiao Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA NSF; NASA; PRF; NSFC; Virginia Tech Geobiology Group; CAS; UNLV; UCR; ASU; UMD; Amherst; Subcommission of Neoproterozoic Stratigraphy; 1 Goals To review biological (e.g., acanthomorphic acritarchs; animals; rangeomorphs; biomineralizing animals), chemical (e.g., carbon and sulfur isotopes, oxygenation of deep oceans), and climatic (e.g., glaciations) events in the Ediacaran Period; To discuss integration and future directions in Ediacaran geobiology; 2 Knoll and Walter, 1992 • Acanthomorphic acritarchs in early and Ediacara fauna in late Ediacaran Period; • Strong carbon isotope variations; • Varanger-Laplandian glaciation; • What has happened since 1992? 3 Age Constraints: South China (538.2±1.5 Ma) 541 Ma Cambrian Dengying Ediacaran Sinian 551.1±0.7 Ma Doushantuo 632.5±0.5 Ma 635 Ma 635.2±0.6 Ma Nantuo (Tillite) 636 ± 5Ma Cryogenian Nanhuan 654 ± 4Ma Datangpo 663±4 Ma Neoproterozoic Neoproterozoic Jiangkou Group Banxi Group 725±10 Ma Tonian Qingbaikouan 1000 Ma • South China radiometric ages: Condon et al., 2005; Hoffmann et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2004; Bowring et al., 2007; S. Zhang et al., 2008; Q. Zhang et al., 2008; • Additional ages from Nama Group (Namibia), Conception Group (Newfoundland), and Vendian (White Sea); 4 The Ediacaran Period Ediacara fossils Cambrian 545 Ma Nama assemblage 555 Ma White Sea assemblage 565 Ma Avalon assemblage 575 Ma 585 Ma Doushantuo biota 595 Ma 605 Ma Ediacaran Period 615 Ma -

The Extent of the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte (Early Cambrian) of North Greenland

The extent of the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte (early Cambrian) of North Greenland JOHN S. PEEL & JON R. INESON Ancillary localities for the Sirius Passet biota (early Cambrian; Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3) are described from the im- mediate vicinity of the main locality on the southern side of Sirius Passet, north-western Peary Land, central North Greenland, where slope mudstones of the Transitional Buen Formation abut against the margin of the Portfjeld Forma- tion carbonate platform. Whilst this geological relationship may extend over more than 500 km east–west across North Greenland, known exposures of the sediments yielding the lagerstätte are restricted to a 1 km long window at the south-western end of Sirius Passet. • Keywords: Early Cambrian, Greenland, lagerstätte. PEEL, J.S. & INESON, J.R. The extent of the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte (early Cambrian) of North Greenland. Bulletin of Geosciences 86(3), 535–543 (4 figures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received March 24, 2011; accepted in revised form July 8, 2011; published online July 28, 2011; issued September 30, 2011. John S. Peel, Department of Earth Sciences (Palaeobiology), Uppsala University, Villavägen 16, SE-75 236 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] • Jon R. Ineson, Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Øster Voldgade 10, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] Almost all of the fossils described from the early Cambrian The first fragmentary fossils from the Sirius Passet Sirius Passet Lagerstätte of northern Peary Land, North Lagerstätte (GGU collection 313035) were collected by Greenland, were collected from a single, west-facing talus A.K. -

Biology of Chordates Video Guide

Branches on the Tree of Life DVD – CHORDATES Written and photographed by David Denning and Bruce Russell ©2005, BioMEDIA ASSOCIATES (THUMBNAIL IMAGES IN THIS GUIDE ARE FROM THE DVD PROGRAM) .. .. To many students, the phylum Chordata doesn’t seem to make much sense. It contains such apparently disparate animals as tunicates (sea squirts), lancelets, fish and humans. This program explores the evolution, structure and classification of chordates with the main goal to clarify the unity of Phylum Chordata. All chordates possess four characteristics that define the phylum, although in most species, these characteristics can only be seen during a relatively small portion of the life cycle (and this is often an embryonic or larval stage, when the animal is difficult to observe). These defining characteristics are: the notochord (dorsal stiffening rod), a hollow dorsal nerve cord; pharyngeal gills; and a post anal tail that includes the notochord and nerve cord. Subphylum Urochordata The most primitive chordates are the tunicates or sea squirts, and closely related groups such as the larvaceans (Appendicularians). In tunicates, the chordate characteristics can be observed only by examining the entire life cycle. The adult feeds using a ‘pharyngeal basket’, a type of pharyngeal gill formed into a mesh-like basket. Cilia on the gill draw water into the mouth, through the basket mesh and out the excurrent siphon. Tunicates have an unusual heart which pumps by ‘wringing out’. It also reverses direction periodically. Tunicates are usually hermaphroditic, often casting eggs and sperm directly into the sea. After fertilization, the zygote develops into a ‘tadpole larva’. This swimming larva shows the remaining three chordate characters - notochord, dorsal nerve cord and post-anal tail. -

Molecular Homology and Multiple-Sequence Alignment: an Analysis of Concepts and Practice

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Systematic Botany, 2015, 28, 46–62 LAS Johnson Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/SB15001 Molecular homology and multiple-sequence alignment: an analysis of concepts and practice David A. Morrison A,D, Matthew J. Morgan B and Scot A. Kelchner C ASystematic Biology, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, Uppsala 75236, Sweden. BCSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. CDepartment of Biology, Utah State University, 5305 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322-5305, USA. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Sequence alignment is just as much a part of phylogenetics as is tree building, although it is often viewed solely as a necessary tool to construct trees. However, alignment for the purpose of phylogenetic inference is primarily about homology, as it is the procedure that expresses homology relationships among the characters, rather than the historical relationships of the taxa. Molecular homology is rather vaguely defined and understood, despite its importance in the molecular age. Indeed, homology has rarely been evaluated with respect to nucleotide sequence alignments, in spite of the fact that nucleotides are the only data that directly represent genotype. All other molecular data represent phenotype, just as do morphology and anatomy. Thus, efforts to improve sequence alignment for phylogenetic purposes should involve a more refined use of the homology concept at a molecular level. To this end, we present examples of molecular-data levels at which homology might be considered, and arrange them in a hierarchy. The concept that we propose has many levels, which link directly to the developmental and morphological components of homology. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology.