Gould Golden Rule Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

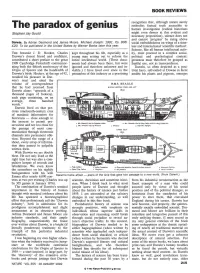

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

The MBL Model and Stochastic Paleontology

216 Chapter seven ised exciting new avenues for research, that insights from biology and ecology could more profi tably be applied to paleontology, and that the future lay in assembling large databases as a foundation for analysis of broad-scale patterns of evolution over geological history. But in compar- ison to other expanding young disciplines—like theoretical ecology— paleobiology lacked a cohesive theoretical and methodological agenda. However, over the next ten years this would change dramatically. Chapter Seven One particular ecological/evolutionary issue emerged as the central unifying problem for paleobiology: the study and modeling of the his- “Towards a Nomothetic tory of diversity over time. This, in turn, motivated a methodological question: how reliable is the fossil record, and how can that reliability be Paleontology”: The MBL Model tested? These problems became the core of analytical paleobiology, and and Stochastic Paleontology represented a continuation and a consolidation of the themes we have examined thus far in the history of paleobiology. Ultimately, this focus led paleobiologists to groundbreaking quantitative studies of the inter- The Roots of Nomotheticism play of rates of origination and extinction of taxa through time, the role of background and mass extinctions in the history of life, the survivor- y the early 1970s, the paleobiology movement had begun to acquire ship of individual taxa, and the modeling of historical patterns of diver- Bconsiderable momentum. A number of paleobiologists began ac- sity. These questions became the central components of an emerging pa- tively building programs of paleobiological research and teaching at ma- leobiological theory of macroevolution, and by the mid 1980s formed the jor universities—Stephen Jay Gould at Harvard, Tom Schopf at the Uni- basis for paleobiologists’ claim to a seat at the “high table” of evolution- versity of Chicago, David Raup at the University of Rochester, James ary theory. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology. -

What Really Happened in the Late Triassic?

Historical Biology, 1991, Vol. 5, pp. 263-278 © 1991 Harwood Academic Publishers, GmbH Reprints available directly from the publisher Printed in the United Kingdom Photocopying permitted by license only WHAT REALLY HAPPENED IN THE LATE TRIASSIC? MICHAEL J. BENTON Department of Geology, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. (Received January 7, 1991) Major extinctions occurred both in the sea and on land during the Late Triassic in two major phases, in the middle to late Carnian and, 12-17 Myr later, at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Many recent reports have discounted the role of the earlier event, suggesting that it is (1) an artefact of a subsequent gap in the record, (2) a complex turnover phenomenon, or (3) local to Europe. These three views are disputed, with evidence from both the marine and terrestrial realms. New data on terrestrial tetrapods suggests that the late Carnian event was more important than the end-Triassic event. For tetrapods, the end-Triassic extinction was a whimper that was followed by the radiation of five families of dinosaurs and mammal- like reptiles, while the late Carnian event saw the disappearance of nine diverse families, and subsequent radiation of 13 families of turtles, crocodilomorphs, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, lepidosaurs and mammals. Also, for many groups of marine animals, the Carnian event marked a more significant turning point in diversification than did the end-Triassic event. KEY WORDS: Triassic, mass extinction, tetrapod, dinosaur, macroevolution, fauna. INTRODUCTION Most studies of mass extinction identify a major event in the Late Triassic, usually placed at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. -

Low-Latitude Origins of the Four Phanerozoic Evolutionary Faunas

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/866186; this version posted December 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Low-Latitude Origins of the Four Phanerozoic Evolutionary Faunas A. Rojas1*, J. Calatayud1, M. Kowalewski2, M. Neuman1, and M. Rosvall1 1Integrated Science Lab, Department of Physics, Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden 5 2Florida Museum of Natural History, Division of Invertebrate Paleontology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract: Sepkoski’s hypothesis of Three Great Evolutionary Faunas that dominated 10 Phanerozoic oceans represents a foundational concept of macroevolutionary research. However, the hypothesis lacks spatial information and fails to recognize ecosystem changes in Mesozoic oceans. Using a multilayer network representation of fossil occurrences, we demonstrate that Phanerozoic oceans sequentially harbored four evolutionary faunas: Cambrian, Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. These mega-assemblages all emerged at low latitudes and dispersed 15 out of the tropics. The Paleozoic–Mesozoic transition was abrupt, coincident with the Permian mass extinction, whereas the Mesozoic–Cenozoic transition was protracted, concurrent with gradual ecological shifts posited by the Mesozoic Marine Revolution. These findings support the notion that long-term ecological changes, historical contingencies, and major geological events all have played crucial roles in shaping the evolutionary history of marine animals. 20 One Sentence Summary: Network analysis reveals that Phanerozoic oceans harbored four evolutionary faunas with variable tempo and underlying causes. -

David M. Raup 1933–2015

David M. Raup 1933–2015 A Biographical Memoir by Michael Foote and Arnold I. Miller ©2017 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. DAVID MALCOLM RAUP April 24, 1933–July 9, 2015 Elected to the NAS, 1979 David M. Raup, one of the most influential paleontolo- gists of the second half of the 20th century, infused the field with concepts from modern biology and established several major lines of research that continue today: Theoretical morphology. Why, despite eons of evolution, is the spectrum of realized biological forms such a tiny fraction of those that are theoretically possible? First-order patterns in the geologic history of biodiversity. Has biodiversity increased steadily over time? What does the answer imply about the biosphere and the nature of the fossil record? Mathematical modeling of evolution. What By Michael Foote patterns result, for example, from the structure of evolu- and Arnold I. Miller tionary trees? And what is the apparent order that emerges from stochastic processes? Biological extinction. What temporal patterns are evident in the history of life and what are their implications for the drivers of extinction and for Earth’s place in the cosmos? The pilot and the paleontologist In The Right Stuff(1979), author Tom Wolfe observed that the calm West Virginia drawl of the renowned test pilot and World War II ace Chuck Yeager could still be heard in the voices of virtually all commercial pilots, decades after Yeager became the first to break the sound barrier. -

Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(S): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S

Paleontological Society Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(s): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba Reviewed work(s): Source: Paleobiology, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 4-15 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400563 . Accessed: 27/08/2012 17:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Paleobiology. http://www.jstor.org Paleobiology,8(1), 1982, pp. 4-15 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form StephenJay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba* Abstract.-Adaptationhas been definedand recognizedby two differentcriteria: historical genesis (fea- turesbuilt by naturalselection for their present role) and currentutility (features now enhancingfitness no matterhow theyarose). Biologistshave oftenfailed to recognizethe potentialconfusion between these differentdefinitions because we have tendedto view naturalselection as so dominantamong evolutionary mechanismsthat historical process and currentproduct become one. Yet if manyfeatures of organisms are non-adapted,but available foruseful cooptation in descendants,then an importantconcept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generallyremain unconsidered):features that now enhance fitnessbut were not built by naturalselection for their current role. -

Darwin's Middle Road∗

Stephen Jay Gould DARWIN'S MIDDLE ROAD∗ "We began to sail up the narrow strait lamenting," narrates Odysseus. "For on the one hand lay Scylla, with twelve feet all dangling down; and six necks exceeding long, and on each a hideous head, and therein three rows of teeth set thick and close, full of black death. And on the other mighty Charybdis sucked down the salt sea water. As often as she belched it forth, like a cauldron on a great fire she would seethe up through all her troubled deeps." Odysseus managed to swerve around Charybdis, but Scylla grabbed six of his finest men and devoured them in his sight-"the most pitiful thing mine eyes have seen of all my travail in searching out the paths of the sea." False lures and dangers often come in pairs in our legends and metaphors—consider the frying pan and the fire, or the devil and the deep blue sea. Prescriptions for avoidance either emphasize a dogged steadiness—the straight and narrow of Christian evangelists—or an averaging between unpleasant alternatives—the golden mean of Aristotle. The idea1 of steering a course between undesirable extremes emerges as a central prescription for a sensible life. The nature of scientific creativity is both a perennial topic of discussion and a prime candidate for seeking a golden mean. The two extreme positions have not been directly competing for allegiance of the unwary. They have, rather, replaced each other sequentially, with one now in the ascendancy, the other eclipsed. The first—inductivism—held that great scientists are primarily great observers and patient accumulators of information. -

The Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Author(S): Stephen P

The neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Author(s): Stephen P. Hubbell Source: Paleobiology, 31(sp5):122-132. 2005. Published By: The Paleontological Society DOI: 10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0122:TNTOBA]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1666/0094- 8373%282005%29031%5B0122%3ATNTOBA%5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Paleobiology,31(2, Supplement),2005,pp.122±132 The neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Stephen P. Hubbell Abstract.ÐNeutral theory in ecology is based on the symmetry assumption that ecologically similar species in a community can be treated as demographically equivalent on a per capita basisÐequiv- alent in birth and death rates, in rates of dispersal, and even in the probability of speciating. Al- though only a ®rst approximation, the symmetry assumption allows the development of a quan- titative neutral theory of relative species abundance and dynamic null hypotheses for the assembly of communities in ecological time and for phylogeny and phylogeography in evolutionary time. -

A New Picture of Life's History on Earth

Commentary A new picture of life’s history on Earth Mark Newman* Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501 hen most people think of paleon- his primary source (2, 3). Other compila- database is as exhaustive as possible, sub- Wtology, they picture the field pale- tions also have been published (4, 5), but stantial biases are introduced. For exam- ontologist digging up fossils with a tooth- Sepkoski’s database has received more ple, it is quite feasible that the increase in brush and publishing descriptions of the attention by far than any other. Sepkoski’s diversity toward recent times seen in Fig. anatomies of uncovered specimens in the database was simple in structure: it re- 1 is a result primarily of the greater vol- trade literature. New discoveries of dino- corded the first and last known occur- ume of rock available from recent times, saurs even make the national headlines. rences in the fossil record of more than and the greater amount of effort that has For many decades the discovery and de- 30,000 marine invertebrate genera in been put into studying these rocks. A scription of a previously unknown fossil about 4,000 families. Marine invertebrates number of studies over the years have species was the calling card that gained have been the focus of most statistical presented evidence showing that apparent would-be paleontologists professional ac- studies, because preservation is much diversity is closely correlated with the ceptance. However, in the last quarter of more reliable in marine environments and intensity with which different periods of a century or so, many of the most intrigu- invertebrates are much more numerous geologic time have been sampled (6, 7). -

Palaeontologia Electronica the Paleobiological Revolution

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org The Paleobiological Revolution: Essays on the Growth of Modern Paleontology Reviewed by Brian Switek David Sepkoski and Michael Ruse (editors) belief that paleon- University of Chicago Press, 2009 tology was more 584 pp., $65.00 (hardcover) closely related to ISBN 978-0-226-74861-0 geology rein- By the middle of the 20th century a great forced the idea divide had opened within evolutionary biology. As that it had little to summarized by paleontologist George Gaylord contribute to the Simpson, many geneticists “said that paleontology life sciences. had no further contributions to make to biology”, Despite this wide- while paleontologists believed that the emerging spread reticence science of genetics “had no significance for the to treat paleontol- true biologist.” (Simpson, 1944). Simpson, for his ogy as an evolu- own part, attempted to bring the disciplines into tionary discipline, accord in his classic Tempo and Mode in Evolution, however, paleon- but despite his efforts genetics eventually out- tologists such as stripped paleontology as the evolutionary science G.G. Simpson and du jour. Paleontology, some evolutionary theorists Norman Newell believed, could only testify to the fact of evolution fostered paleobiological research through the while telling us nothing of how such changes actu- 1950’s and 1960’s, setting a long fuse that finally ally occurred. Fortunately, however, some paleon- exploded in the 1970’s. Thomas Schopf, Niles tologists were not satisfied with this blinkered view Eldredge, Stephen Jay Gould, Elisabeth Vrba, of their discipline, and they began what historians David Raup, James Valentine, Jack Sepkoski, and David Sepkoski and Michael Ruse have called The many others transformed paleontology from a rela- Paleobiological Revolution. -

Opus 200 - Stephen Jay Gould

Opus 200 - Stephen Jay Gould Natural History, August 1991, 100 (8):12-18 In my adopted home of Puritan New England, I have learned that personal indulgence is a vice to be tolerated only at rare intervals. Combine this stricture with two further principles and this essay achieves its rationale: first, that we celebrate in hundreds and their easy multiples (the Columbian quincentenary and the fiftieth anniversary of DiMaggio's hitting streak—both about equally important, and only the latter an unambiguous good); second, that geologists learn to take the long view. This is my 200th essay in "This View of Life," a series begun in January 1974 (with never an issue missed). If once is an incident and twice a tradition, I now establish an indulgence for even multiples of 100 only. Essays must express the personal thoughts and prejudices of authors—for this has been the genre's definition ever since Montaigne. But I have tried not to abuse the bully pulpit of this forum to act as a shill for my own professional research and theorizing. Still, once in a hundred shouldn't subvert my bonae fides, so I indulge, as I did once before at my own centenary. Essay 100 treated the Bahamian land snails that usurp the bulk of my time for empirical research. Opus 200 shall discuss the theoretical idea most central to my work— punctuated equilibrium. Moreover, Niles Eldredge and I formulated the theory of punctuated equilibrium in 1971, and I can scarcely resist the double whammy of 200 essays on the twentieth anniversary of "punk eke," the affectionate nickname used by supporters, while detractors have parried with "evolution by jerks." Punctuated equilibrium began, as so much else that later looms large in our lives, as a little path that might never have opened.