The Palaeontology Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproduction in Plants Which But, She Has Never Seen the Seeds We Shall Learn in This Chapter

Reproduction in 12 Plants o produce its kind is a reproduction, new plants are obtained characteristic of all living from seeds. Torganisms. You have already learnt this in Class VI. The production of new individuals from their parents is known as reproduction. But, how do Paheli thought that new plants reproduce? There are different plants always grow from seeds. modes of reproduction in plants which But, she has never seen the seeds we shall learn in this chapter. of sugarcane, potato and rose. She wants to know how these plants 12.1 MODES OF REPRODUCTION reproduce. In Class VI you learnt about different parts of a flowering plant. Try to list the various parts of a plant and write the Asexual reproduction functions of each. Most plants have In asexual reproduction new plants are roots, stems and leaves. These are called obtained without production of seeds. the vegetative parts of a plant. After a certain period of growth, most plants Vegetative propagation bear flowers. You may have seen the It is a type of asexual reproduction in mango trees flowering in spring. It is which new plants are produced from these flowers that give rise to juicy roots, stems, leaves and buds. Since mango fruit we enjoy in summer. We eat reproduction is through the vegetative the fruits and usually discard the seeds. parts of the plant, it is known as Seeds germinate and form new plants. vegetative propagation. So, what is the function of flowers in plants? Flowers perform the function of Activity 12.1 reproduction in plants. Flowers are the Cut a branch of rose or champa with a reproductive parts. -

Feeding-Dependent Tentacle Development in the Sea Anemone Nematostella Vectensis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.12.985168; this version posted March 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Feeding-dependent tentacle development in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis Aissam Ikmi1,2*, Petrus J. Steenbergen1, Marie Anzo1, Mason R. McMullen2,3, Anniek Stokkermans1, Lacey R. Ellington2, and Matthew C. Gibson2,4 Affiliations: 1Developmental Biology Unit, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany. 2Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Kansas City, Missouri 64110, USA. 3Department of Pharmacy, The University of Kansas Health System, Kansas City, Kansas 66160, USA. 4Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, The University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kansas 66160, USA. *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.12.985168; this version posted March 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Summary In cnidarians, axial patterning is not restricted to embryonic development but continues throughout a prolonged life history filled with unpredictable environmental changes. How this developmental capacity copes with fluctuations of food availability and whether it recapitulates embryonic mechanisms remain poorly understood. To address these questions, we utilize the tentacles of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis as a novel paradigm for developmental patterning across distinct life history stages. -

The Ediacaran Frondose Fossil Arborea from the Shibantan Limestone of South China

Journal of Paleontology, 94(6), 2020, p. 1034–1050 Copyright © 2020, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/20/1937-2337 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2020.43 The Ediacaran frondose fossil Arborea from the Shibantan limestone of South China Xiaopeng Wang,1,3 Ke Pang,1,4* Zhe Chen,1,4* Bin Wan,1,4 Shuhai Xiao,2 Chuanming Zhou,1,4 and Xunlai Yuan1,4,5 1State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Palaeoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China <[email protected]><[email protected]> <[email protected]><[email protected]><[email protected]><[email protected]> 2Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061, USA <[email protected]> 3University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China 4University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 5Center for Research and Education on Biological Evolution and Environment, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China Abstract.—Bituminous limestone of the Ediacaran Shibantan Member of the Dengying Formation (551–539 Ma) in the Yangtze Gorges area contains a rare carbonate-hosted Ediacara-type macrofossil assemblage. This assemblage is domi- nated by the tubular fossil Wutubus Chen et al., 2014 and discoidal fossils, e.g., Hiemalora Fedonkin, 1982 and Aspidella Billings, 1872, but frondose organisms such as Charnia Ford, 1958, Rangea Gürich, 1929, and Arborea Glaessner and Wade, 1966 are also present. -

The Eocene Arctic Azolla Bloom: Environmental Conditions, Productivity and Carbon Drawdown

Geobiology (2009), 7, 155–170 DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00195.x TheBlackwell Publishing Ltd Eocene Arctic Azolla bloom: environmental conditions, productivity and carbon drawdown E. N. SPEELMAN,1 M. M. L. VAN KEMPEN,2 J. BARKE,3 H. BRINKHUIS,3 G. J. REICHART,1 A. J. P. SMOLDERS,2 J. G. M. ROELOFS,2 F. SANGIORGI,3 J. W. DE LEEUW,1,3,4 A. F. LOTTER3 AND J. S. SINNINGHE DAMSTÉ1,4 1Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands 2Department of Aquatic Ecology and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Science, Radboud University, Heyendaalseweg 135, 6525 AJ, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 3Institute of Environmental Biology, Laboratory of Palaeobotany and Palynology, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands 4NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Department of Marine Organic Biogeochemistry, PO Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands ABSTRACT Enormous quantities of the free-floating freshwater fern Azolla grew and reproduced in situ in the Arctic Ocean during the middle Eocene, as was demonstrated by microscopic analysis of microlaminated sediments recovered from the Lomonosov Ridge during Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 302. The timing of the Azolla phase (~48.5 Ma) coincides with the earliest signs of onset of the transition from a greenhouse towards the modern icehouse Earth. The sustained growth of Azolla, currently ranking among the fastest growing plants on Earth, in a major anoxic oceanic basin may have contributed to decreasing atmospheric pCO2 levels via burial of Azolla-derived organic matter. The consequences of these enormous Azolla blooms for regional and global nutrient and carbon cycles are still largely unknown. -

A Mysterious Giant Ichthyosaur from the Lowermost Jurassic of Wales

A mysterious giant ichthyosaur from the lowermost Jurassic of Wales JEREMY E. MARTIN, PEGGY VINCENT, GUILLAUME SUAN, TOM SHARPE, PETER HODGES, MATT WILLIAMS, CINDY HOWELLS, and VALENTIN FISCHER Ichthyosaurs rapidly diversified and colonised a wide range vians may challenge our understanding of their evolutionary of ecological niches during the Early and Middle Triassic history. period, but experienced a major decline in diversity near the Here we describe a radius of exceptional size, collected at end of the Triassic. Timing and causes of this demise and the Penarth on the coast of south Wales near Cardiff, UK. This subsequent rapid radiation of the diverse, but less disparate, specimen is comparable in morphology and size to the radius parvipelvian ichthyosaurs are still unknown, notably be- of shastasaurids, and it is likely that it comes from a strati- cause of inadequate sampling in strata of latest Triassic age. graphic horizon considerably younger than the last definite Here, we describe an exceptionally large radius from Lower occurrence of this family, the middle Norian (Motani 2005), Jurassic deposits at Penarth near Cardiff, south Wales (UK) although remains attributable to shastasaurid-like forms from the morphology of which places it within the giant Triassic the Rhaetian of France were mentioned by Bardet et al. (1999) shastasaurids. A tentative total body size estimate, based on and very recently by Fischer et al. (2014). a regression analysis of various complete ichthyosaur skele- Institutional abbreviations.—BRLSI, Bath Royal Literary tons, yields a value of 12–15 m. The specimen is substantially and Scientific Institution, Bath, UK; NHM, Natural History younger than any previously reported last known occur- Museum, London, UK; NMW, National Museum of Wales, rences of shastasaurids and implies a Lazarus range in the Cardiff, UK; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, lowermost Jurassic for this ichthyosaur morphotype. -

Rinded, Iron-Oxide Concretions in Navajo Sandstone Along the Trail to Upper Calf Creek Falls, Garfield County

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences of 2019 Rinded, Iron-Oxide Concretions in Navajo Sandstone Along the Trail to Upper Calf Creek Falls, Garfield County David Loope Richard Kettler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. M. Milligan, R.F. Biek, P. Inkenbrandt, and P. Nielsen, editors 2019 Utah Geological Association Publication 48 Rinded, Iron-Oxide Concretions in Navajo Sandstone Along the Trail to Upper Calf Creek Falls, Garfield County David B. Loope and Richard M. Kettler Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, University of Nebraska Lincoln, NE 68588-0340 [email protected] Utah Geosites 2019 Utah Geological Association Publication 48 M. Milligan, R.F. Biek, P. Inkenbrandt, and P. Nielsen, editors Cover Image: View of a concretion along a trail in Upper Calf Creek Falls. M. Milligan, R.F. Biek, P. Inkenbrandt, and P. Nielsen, editors 2019 Utah Geological Association Publication 48 Presidents Message I have had the pleasure of working with many diff erent geologists from all around the world. As I have traveled around Utah for work and pleasure, many times I have observed vehicles parked alongside the road with many people climbing around an outcrop or walking up a trail in a canyon. -

Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province

Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province, Virginia and West Virginia— A Field Trip Guidebook for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Eastern Section Meeting, September 28–29, 2011 Open-File Report 2012–1194 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province, Virginia and West Virginia— A Field Trip Guidebook for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Eastern Section Meeting, September 28–29, 2011 By Catherine B. Enomoto1, James L. Coleman, Jr.1, John T. Haynes2, Steven J. Whitmeyer2, Ronald R. McDowell3, J. Eric Lewis3, Tyler P. Spear3, and Christopher S. Swezey1 1U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA 20192 2 James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA 22807 3 West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, Morgantown, WV 26508 Open-File Report 2012–1194 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Ken Salazar, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

BRAGEN LIST Established by Rex Doescher JAN 19,1996 13:38 GENUS AUTHOR DATE RANGE

BRAGEN LIST established by Rex Doescher JAN 19,1996 13:38 GENUS AUTHOR DATE RANGE SUPERFAMILY: ACROTRETACEA ACROTHELE LINNARSSON 1876 CAMBRIAN ACROTHYRA MATTHEW 1901 CAMBRIAN AKMOLINA POPOV & HOLMER 1994 CAMBRIAN AMICTOCRACENS HENDERSON & MACKINNON 1981 CAMBRIAN ANABOLOTRETA ROWELL & HENDERSON 1978 CAMBRIAN ANATRETA MEI 1993 CAMBRIAN ANELOTRETA PELMAN 1986 CAMBRIAN ANGULOTRETA PALMER 1954 CAMBRIAN APHELOTRETA ROWELL 1980 CAMBRIAN APSOTRETA PALMER 1954 CAMBRIAN BATENEVOTRETA USHATINSKAIA 1992 CAMBRIAN BOTSFORDIA MATTHEW 1891 CAMBRIAN BOZSHAKOLIA USHATINSKAIA 1986 CAMBRIAN CANTHYLOTRETA ROWELL 1966 CAMBRIAN CERATRETA BELL 1941 1 Range BRAGEN LIST - 1996 CAMBRIAN CURTICIA WALCOTT 1905 CAMBRIAN DACTYLOTRETA ROWELL & HENDERSON 1978 CAMBRIAN DEARBORNIA WALCOTT 1908 CAMBRIAN DIANDONGIA RONG 1974 CAMBRIAN DICONDYLOTRETA MEI 1993 CAMBRIAN DISCINOLEPIS WAAGEN 1885 CAMBRIAN DISCINOPSIS MATTHEW 1892 CAMBRIAN EDREJA KONEVA 1979 CAMBRIAN EOSCAPHELASMA KONEVA & AL 1990 CAMBRIAN EOTHELE ROWELL 1980 CAMBRIAN ERBOTRETA HOLMER & USHATINSKAIA 1994 CAMBRIAN GALINELLA POPOV & HOLMER 1994 CAMBRIAN GLYPTACROTHELE TERMIER & TERMIER 1974 CAMBRIAN GLYPTIAS WALCOTT 1901 CAMBRIAN HADROTRETA ROWELL 1966 CAMBRIAN HOMOTRETA BELL 1941 CAMBRIAN KARATHELE KONEVA 1986 CAMBRIAN KLEITHRIATRETA ROBERTS 1990 CAMBRIAN 2 Range BRAGEN LIST - 1996 KOTUJOTRETA USHATINSKAIA 1994 CAMBRIAN KOTYLOTRETA KONEVA 1990 CAMBRIAN LAKHMINA OEHLERT 1887 CAMBRIAN LINNARSSONELLA WALCOTT 1902 CAMBRIAN LINNARSSONIA WALCOTT 1885 CAMBRIAN LONGIPEGMA POPOV & HOLMER 1994 CAMBRIAN LUHOTRETA MERGL & SLEHOFEROVA -

Skeletonized Microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian Transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, Northern Spain

Skeletonized microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain SÉBASTIEN CLAUSEN and J. JAVIER ÁLVARO Clausen, S. and Álvaro, J.J. 2006. Skeletonized microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (2): 223–238. Two different assemblages of skeletonized microfossils are recorded in bioclastic shoals that cross the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary in the Esla nappe, Cantabrian Mountains. The uppermost Lower Cambrian sedimentary rocks repre− sent a ramp with ooid−bioclastic shoals that allowed development of protected archaeocyathan−microbial reefs. The shoals yield abundant debris of tube−shelled microfossils, such as hyoliths and hyolithelminths (Torellella), and trilobites. The overlying erosive unconformity marks the disappearance of archaeocyaths and the Iberian Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary. A different assemblage occurs in the overlying glauconitic limestone associated with development of widespread low−relief bioclastic shoals. Their lowermost part is rich in hyoliths, hexactinellid, and heteractinid sponge spicules (Eiffelia), chancelloriid sclerites (at least six form species of Allonnia, Archiasterella, and Chancelloria), cambroclaves (Parazhijinites), probable eoconchariids (Cantabria labyrinthica gen. et sp. nov.), sclerites of uncertain af− finity (Holoplicatella margarita gen. et sp. nov.), echinoderm ossicles and trilobites. Although both bioclastic shoal com− plexes represent similar high−energy conditions, the unconformity at the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary marks a drastic replacement of microfossil assemblages. This change may represent a real community replacement from hyolithelminth−phosphatic tubular shells to CES (chancelloriid−echinoderm−sponge) meadows. This replacement coin− cides with the immigration event based on trilobites previously reported across the boundary, although the partial infor− mation available from originally carbonate skeletons is also affected by taphonomic bias. -

Progress in Echinoderm Paleobiology

Journal of Paleontology, 91(4), 2017, p. 579–581 Copyright © 2017, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/17/0088-0906 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2017.20 Progress in echinoderm paleobiology Samuel Zamora1,2 and Imran A. Rahman3 1Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME), C/Manuel Lasala, 44, 9ºB, 50006, Zaragoza, Spain 〈[email protected]〉 2Unidad Asociada en Ciencias de la Tierra, Universidad de Zaragoza-IGME, Zaragoza, Spain 3Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom 〈[email protected]〉 Echinoderms are a diverse and successful phylum of exclusively Universal elemental homology (UEH) has proven to be one marine invertebrates that have an extensive fossil record dating of the most powerful approaches for understanding homology back to Cambrian Stage 3 (Zamora and Rahman, 2014). There in early pentaradial echinoderms (Sumrall, 2008, 2010; Sumrall are five extant classes of echinoderms (asteroids, crinoids, and Waters, 2012; Kammer et al., 2013). This hypothesis echinoids, holothurians, and ophiuroids), but more than 20 focuses on the elements associated with the oral region, extinct groups, all of which are restricted to the Paleozoic identifying possible homologies at the level of specific plates. (Sumrall and Wray, 2007). As a result, to fully appreciate the Two papers, Paul (2017) and Sumrall (2017), deal with the modern diversity of echinoderms, it is necessary to study their homology of plates associated with the oral area in early rich fossil record. pentaradial echinoderms. The former contribution describes and Throughout their existence, echinoderms have been an identifies homology in various ‘cystoid’ groups and represents a important component of marine ecosystems. -

Ocean Drilling Program Scientific Results Volume

von Rad, U., Haq, B. U., et al., 1992 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 122 24. TRIASSIC FORAMINIFERS FROM SITES 761 AND 764, WOMBAT PLATEAU, NORTHWEST AUSTRALIA1 Louisette Zaninetti,2 Rossana Martini,2 and Thierry Dumont3 ABSTRACT The Late Triassic foraminifers encountered in the cores from ODP Leg 122 Sites 761 and 764 are, on the basis of Triasina oberhauseri and Triasina hantkeni, late Norian and Rhaetian (Jriasina hantkeni Biozone) in age. The reefal carbonate platform penetrated at both sites is characterized by inner shelf (intertidal to lagoon), patch reef, and outer shelf facies. INTRODUCTION major break between the two. This is in turn overlain at Site 761 by a sharp sedimentary break followed by a new shallow- Upper Triassic sediments were drilled offshore northwest ing-upward sedimentary sequence of Rhaetian age, which is Australia in 1988 during Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg capped by the postrift unconformity and comprises schemat- 122 (Haq, von Rad, et al., 1990). Four sites (759, 760, 761, and ically two units: (1) a lower, terrigenous-rich, transgressive 764) were drilled on the Wombat Plateau, the northern prom- unit showing both shallow open-marine and external platform ontory of the Exmouth Plateau (von Rad et al., 1989a; Fig. environments and (2) an upper regressive carbonate unit with 1 A). These sites provided the opportunity for reconstructing a lagoonal to intertidal deposits. A third overlying unit recov- composite section of Upper Triassic cores from the Carnian to ered at Site 764 does not exist at Site 761 because of Jurassic the Rhaetian, because the Wombat Plateau experienced non- erosion. -

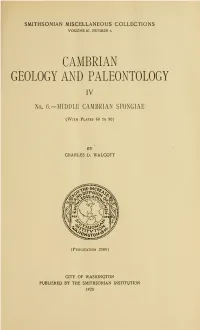

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 67, NUMBER 6 CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY IV No. 6.—MIDDLE CAMBRIAN SPONGIAE (With Plates 60 to 90) BY CHARLES D. WALCOTT (Publication 2580) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION 1920 Z$t Bovb Qgattimote (press BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY IV No. 6.—MIDDLE CAMBRIAN SPONGIAE By CHARLES D. WALCOTT (With Plates 60 to 90) CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 263 Habitat = 265 Genera and species 265 Comparison with recent sponges 267 Comparison with Metis shale sponge fauna 267 Description of species 269 Sub-Class Silicispongiae 269 Order Monactinellida Zittel (Monaxonidae Sollas) 269 Sub-Order Halichondrina Vosmaer 269 Halichondrites Dawson 269 Halichondrites elissa, new species 270 Tuponia, new genus 271 Tuponia lineata, new species 272 Tuponia bellilineata, new species 274 Tuponia flexilis, new species 275 Tuponia flexilis var. intermedia, new variety 276 Takakkawia, new genus 277 Takakkawia lineata, new species 277 Wapkia, new genus 279 Wapkia grandis, new species 279 Hazelia, new genus 281 Hazelia palmata, new species 282 Hazelia conf erta, new species 283 Hazelia delicatula, new species 284 Hazelia ? grandis, new species 285. Hazelia mammillata, new species 286' Hazelia nodulifera, new species 287 Hazelia obscura, new species 287 Corralia, new genus 288 Corralia undulata, new species 288 Sentinelia, new genus 289 Sentinelia draco, new species 290 Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 67, No. 6 261 262 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 6j Family Suberitidae 291 Choia, new genus 291 Choia carteri, new species 292 Choia ridleyi, new species 294 Choia utahensis, new species 295 Choia hindei (Dawson) 295 Hamptonia, new genus 296 Hamptonia bowerbanki, new species 297 Pirania, new genus 298 Pirania muricata, new species 298 Order Hexactinellida O.