KIPLING JOURNAL 1 2 KIPLING JOURNAL June 2007 June 2007 KIPLING JOURNAL 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15 2016 F O U R C E N T U R I

F O U R C E N T U R I E S Russian Poetry in Translation 15 2016 Four Centuries. Russian Poetry in Translation [email protected] Copyright © 2016 by Dr. Ilya Perelmuter, Publisher All rights to translations and materials published in this magazine are retained by the individual translators and authors. No part of this magazine may be reproduced, copied, transmitted, distributed or otherwise used without the prior permission of the Publisher. This magazine as a whole can be sent indissolubly per e-mail as a pdf file. Commercial distribution is not allowed. This magazine should be cited as follows: Four Centuries. Russian Poetry in Translation. Essen: Perelmuter Verlag, 2016, Nr. 15 Все права на переводы и другие материалы, опубликованные в этом журнале, в полном объёме сохраняются за отдельными переводчиками и авторами. Журнал защищён авторским правом в совокупности всех его частей и в полном объёме. Любые типы копирования, перепечатки, распространения, публикации его отдельных частей без согласия издателя не разрешаются. Журнал может быть послан по электронной почте с сохранением его целостности в формате pdf. Журнал без нарушения его целостности может быть включён в электронную библиотеку с уведомлением об этом издателя. Коммерческое распространение журнала запрещено. Цитирование материалов журнала обязательно в следующей форме: Four Centuries. Russian Poetry in Translation. Essen: Perelmuter Verlag, 2016, Nr. 15 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to the poets: David Shrayer-Petrov, Felix Chechik, Anna Glazova, Sergej Shestakov, Andrej Sen-Senkov, and Vera Polozkova for their kind permissions to publish their poems in translation in this issue of the magazine. Publisher Perelmuter Verlag, Dr. Ilya Perelmuter, Publisher Erikapfad 7, 45133 Essen, Germany www.perelmuterverlag.de, [email protected] C O N T E N T S Letter from the Publisher 4 XIX Konstantin Batyushkov Константин Батюшков To Dashkov 5 К Д<ашко>ву 5 Konstantin Aksakov Константин Аксаков To Sophie 8 Софье 8 Dmitry Minayev Дмитрий Минаев From the Cycle "Motifs of the Russian Poets". -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

Detki V Kletke: the Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry

Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Morse, Ainsley. 2016. Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493521 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry A dissertation presented by Ainsley Elizabeth Morse to The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Slavic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Ainsley Elizabeth Morse. All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Stephanie Sandler Ainsley Elizabeth Morse Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry Abstract Since its inception in 1918, Soviet children’s literature was acclaimed as innovative and exciting, often in contrast to other official Soviet literary production. Indeed, avant-garde artists worked in this genre for the entire Soviet period, although they had fallen out of official favor by the 1930s. This dissertation explores the relationship between the childlike aesthetic as expressed in Soviet children’s literature, the early Russian avant-garde and later post-war unofficial poetry. -

The Jews of Simferopol

BE'H The Jews of Simferopol This article is dedicated to two of our grandsons who are now Israeli soldiers: Daniel Prigozin and Yonaton Inegram. Esther (Herschman) Rechtschafner Kibbutz Ein-Zurim 2019 Table of Contents Page Introduction 1 Basic Information about Simferopol 2 Geography 2 History 3 Jewish History 4 The Community 4 The Holocaust 6 After the Holocaust 8 Conclusion 11 Appendices 12 Maps 12 Photos 14 Bibliography 16 Internet 16 Introduction The story of why I decided to write about the history of Simferopol is as follows. As many know, I have written a few articles and organized a few websites1. All of these are in connection to the places in Eastern Europe that my extend family comes from. A short while ago Professor Jerome Shapiro2,who had previously sent me material about his family for my Sveksna website wrote me an email and mentioned that he would like to have an article written about the place where his wife's family comes from: Simferopol, Crimea. Since I did not know anything about this place, I decided to take this upon myself as a challenge. This meant: 1. researching a place that I am not emotionally attached to 2. finding material about a place that is not well known 3. finding a website for placement of the article With the help of people I know by way of my previous researching3, people I met while looking for information, the internet (and the help of G-d), I felt that I had enough information to write an article. While researching for material for this article, I became acquainted with Dr. -

COMPARATIVE STUDY of 1930S PICTUREBOOKS by SAMUIL

Sara Pankenier Weld THE OBLITERATION OF THE AVANT- GARDE AESTHETIC: COMPARATIVE STUDY OF 1930s PICTUREBOOKS BY SAMUIL MARSHAK Basing its findings on word and image analysis, this article seeks to juxtapose images from early and later editions of classic picturebooks authored by Samuil Marshak and illustrated by Vladimir Lebedev or Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, namely Вчера и сегодня (Yesterday and Today), Багаж (Baggage), Мистер Твистер (Mister Twister), and Почта (The Mail), to expose changes necessitated by new artistic and political circumstances as picturebooks for children increasingly became a territory of conflict. Contrasts revealed by comparative visual analysis offer insights into the restrictions and adaptations illustrators made as the avant-garde aesthetic came under fire and children’s literature began to face increasing censorship. These changes reveal the fingerprints of ideology and censorship in an intermediate stage when a kind of hybridization of the avant-garde was occurring, just before the complete obliteration of the avant- garde aesthetic. Keywords: Soviet, picturebooks, illustration, avant-garde, censorship, Samuil Marshak, Vladimir Lebedev, Mikhail Tsekhanovsky. Comparative study of rare 1930s editions of classic picturebooks authored by Samuil Marshak and illustrated by leading avant-garde illustrators Vladimir Lebedev and Mikhail Tsekhanovsky exposes revealing changes necessitated by new artistic and political circumstances as picturebooks for children increasingly became a territory of conflict. Basing its findings -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

On the Topics and Style of Soviet Animated Films

BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2016 / VOLUME 4 / ARTICLE Article On the Topics and Style of Soviet Animated Films ÜLO PIKKOV, Estonian Academy of Arts; email: [email protected] 16 DOI: 10.1515/bsmr-2017-0002 BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2016 / VOLUME 4 / ARTICLE ABSTRACT This article provides a survey of Soviet animation and analyses the thematic and stylistic course of its develop- ment. Soviet animated film emerged and materialised in synch with the fluctuations of the region’s political climate and was directly shaped by it. A number of trends and currents of Soviet animation also pertain to other Eastern European countries. After all, Eastern Europe constituted an integrated cultural space that functioned as a single market for the films produced across it by filmmakers who interacted in a professional regional network of film education, events, festivals, publications etc. Initially experimental, post-revolutionary Russian ani- mation soon fell under the sway of the Socialist Realist discourse, along with the rest of Soviet art, and quickly crystallised as a didactic genre for children. Disney’s para- digm became its major source of inspiration both in terms of visual style and thematic scope, despite the fact that Soviet Union was regarded as the ideological opposite of the Western way of life and mindset. The Soviet animation industry was spread across different studios and republics that adopted slightly varied production practices and tolerated different degrees of artistic freedom. Studios in the smaller republics, such as Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in particular, stood out for making films that were more ideologically complicated than those produced in Moscow. -

Shelley in the Transition to Russian Symbolism

SHELLEY IN THE TRANSITION TO RUSSIAN SYMBOLISM: THREE VERSIONS OF ‘OZYMANDIAS’ David N. Wells I Shelley is a particularly significant figure in the early development of Russian Symbolism because of the high degree of critical attention he received in the 1880s and 1890s when Symbolism was rising as a literary force in Russia, and because of the number and quality of his translators. This article examines three different translations of Shelley’s sonnet ‘Ozymandias’ from the period. Taken together, they show that the English poet could be interpreted in different ways in order to support radically different aesthetic ideas, and to reflect both the views of the literary establishment and those of the emerging Symbolist movement. At the same time the example of Shelley confirms a persistent general truth about literary history: that the literary past is constantly recreated in terms of the present, and that a shared culture can be used to promote a changing view of the world as well as to reinforce the status quo. The advent of Symbolism as a literary movement in Russian literature is sometimes seen as a revolution in which a tide of individualism, prompted by a crisis of faith at home, and combined with a new sense of form drawing on French models, replaced almost overnight the positivist and utilitarian traditions of the 1870s and 1880s with their emphasis on social responsibility and their more conservative approach to metre, rhyme and poetic style.1 And indeed three landmark literary events marking the advent of Symbolism in Russia occurred in the pivotal year of 1892 – the publication of Zinaida Vengerova’s groundbreaking article on the French Symbolist poets in Severnyi vestnik, the appearance of 1 Ronald E. -

T. S. Eliot's “Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats” In

УДК 821.111-1. DOI 10.51762/1FK-2021-26-02-16. ББК Ш33(7Сое)64-8,45. ГРНТИ 17.07.29. Код ВАК 10.01.03 T. S. ELIOT’S “OLD POSSUM’S BOOK OF PRACTICAL CATS” IN THE CONTEXT OF “NURSERY RHYMES” TRADITION Kristina M. Marshaniya Tyumen State University (Tyumen, Russia) ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0218-0079 Abstract. This paper presents the results of a comparative study of the collection of poemsOld Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939) by T. S. Eliot and the collection of children’s verses Mother Goose Old Nursery Rhymes (published in 1760), compiled and illustrated by A. Rackham (1913). Consisting of 15 poems, and distinguished by its frivolity against the background of other works by Eliot, the cycle Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats has been overlooked by both Russian and foreign researchers for a long time. Recently a surge of interest in this book of verse has been provoked by the release of a feature film Cats (2019) based on the world-famous musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber. This fact as well as the lack of serious academic studies of Eliot’s book of verse has determined the urgency and novelty of this paper. It is also important to show the involvement of this segment of Eliot’s poetry into the En- glish literary tradition. The aim of this research is to identify the influence of Victorian aesthetics of nonsense on the poetry of T. S. Eliot’s cycle. The method of comparative analysis has been chosen as the main research method. -

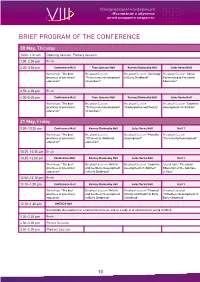

Brief.Program.Of.The.Conference

BrIef program of the conFerenCe 30 May,.thirsday 10 00–1. 30. .am opening.Session,.Plenary.Session 1 .30–2 .30.pm Break 2 .30–3 .50.pm Conference-Hall Tove Jansson Hall Korney Chukovsky Hall Jules Verne Hall Hall 1 Hall 9 Hall 7 Samuil Marshak Hall Workshops."the best Breakout.Session. Breakout.Session."sociology Breakout.Session."social round.table.."Quality of early Breakout.Session."ecological Breakout.Session."threats to Partner-region.Sakha.(Yakutiya) practices of preschool "Professional development of early childhood" Partnership in Preschool childhood education education for sustainable Psychological health of children: education" of teachers" education" development of children" risk areas and ways of recovery" 3 .50–4 .00.pm Break 4 .00–5 .20.pm Conference-Hall Tove Jansson Hall Korney Chukovsky Hall Jules Verne Hall Hall 1 Hall 9 Hall 7 Samuil Marshak Hall Workshops."the best Breakout.Session. Breakout.Session. Breakout.Session."cognitive Breakout.Session."mathematics Breakout.Session."early Breakout.Session."Preschool Partner-region.Sakha.(Yakutiya) practices of preschool "Professional development "Kindergarten and family" development of children" in Preschool" childhood education in the era education administrating" education" of teachers" of digitalization: multimedia technology" 31 May,.friday 9 .00–10 .25.am Conference-Hall Korney Chukovsky Hall Jules Verne Hall Hall 1 Hall 2 Hall 5 Gianni Rodari Hall Lewis Carroll Hall Workshops."the best Breakout.Session. Breakout.Session."morality Breakout.Session. Breakout.Session."toddler -

Shakespeare's Sonnets in Russian

Shakespeare’s Sonnets in Russian: The Challenge of Translation Elena Rassokhina Umeå Studies in Language and Literature 37 Department of Language Studies Umeå University 2017 Department of Language Studies Umeå University SE-901 87 Umeå http://www.sprak.umu.se This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) © 2017 Elena Rassokhina ISBN: 978-91-7601-681-7 Front cover illustration: Elena Rassokhina, Aleksei Zakharov, Anja Rassokhina Electronic version accessible via http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Umeå Studies in Language and Literature 37 Printed by: Print & media, Umeå University Distributed by: eddy.se ab, Visby Umeå, Sweden 2017 To study Shakespeare in translation is just another way to find him. Ton Hoenselaars The translation of verse is impossible. Every time is an exception. Samuil Marshak Table of Contents Table of Contents i Abstract iii List of Articles v Acknowledgements vii A note on transliteration and translation ix Preface 1 1. Introduction 3 1.1. Shakespeare’s sonnets as a Russian literary phenomenon 3 1.2. Objectives of the research and methodology 5 1.3. Disposition of the thesis 6 1.4. Sources and limitations 7 1.5. Critical studies of the sonnets and their translations into Russian 8 1.6. Theoretical background 11 1.6.1. Translation and norms 11 1.6.2. Translation as rewriting 12 1.6.3. Translations and retranslations 13 1.6.4. Translatability and poetic translation 17 2. The context of Shakespeare’s sonnets 25 2.1. The sonnets and translation competence 25 2.2. Date of composition and the author’s intentions 26 2.3. -

Kipling's India

r^ \\ui; .-i ^ JiU ,-^'» 57^ ~ -< '•^/iad/MiN. rnr nFfM' 5er 21 '.\\F!INIV inriitrrrr-- .T-iin-^A r\\ r ^ . t^ i in r. * r.'i iUl- /A "' — .^"'.^OFCAlIfO/?^,-"»;^. 5:>^Of( \ .•.v\^_ KIPLING'S INDIA KIPLING'S INDIA BY ARLEY MUNSON " Author of Jungle Days, Being the Experiences of an American Woman Physician in India" Illustrated QABDEN CITY NEW TOBK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1915 Copyright, 1915, by DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & COMPANY All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY DODD, MEAD & COMPANY c w c c I c "111 ' C I 1 < ( I L I J ^ TO MY SISTERS, MARY WOOSTER SUTTON AND GERTRUDE MUNSON HULST CONTENTS Introduction ^* "^A^^ CHAPTER 5 ^ I. The Threshold of India <^ II. Anglo-India H 57 V III. The Himalayas IV. The Great Desert 69 V. The Border Country 89 Oldest Land 127 r^^ VI. The VII. On the Road to Mandalay 175 Index 1^^ vu 456893 ILLUSTRATIONS Looking toward Kabul. "The mountains . tall and black" and "bitter cold" . Frontispiece FACING PAGE Simla from the Kalka Road . 12 Cottages of Anglo-Indians at Simla 18 The Heart of Rudyard Kipling's Anglo-India . 22 The Solemn Deodars 26 Simla from the Tara Devi ........ 26 The Road Down Elysium Hill 26 Simla: Viceregal Lodge 30 Simla: Before Christ Church 36 Jakko Hill: "Deodar-Crowned Jakko" .... 40 The Broad Road Around Jakko 44 Simla: the Lower Bazaar 48 "Tibetan Devil-dance Masks" 58 "Oh, the Hills and the Snow upon the Hills." "Kim" 58 An Old Gate in the Walled City of Lahore ..