Public Procurement, Fair Trade Governance and Sustainable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gospel and Globalization

the Gospel and Globalization Exploring the Religious Roots of a Globalized World Edited by Michael W. Goheen Erin G. Glanville Regent College Press • Geneva Society Vancouver, B.C., Canada THE GOSPEL AND GLOBALIZATION: EXPLORING THE RELIGIOUS ROOTS OF A GLOBALIZED WORLD Copyright © 2009 Regent College Publishing All rights reserved. Published 2009 by REGENT COLLEGE PUBLISHING 5800 University Boulevard / Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 2E4 / Canada / www.regentpublishing.com with GENEVA SOCIETY www.genevasociety.org Cover image by Ben Goheen Typeset by Dan Postma No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or the Copyright Licensing Agency. Views expressed in works published by Regent College Publishing are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Regent College (www.regent-college.edu). Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication The Gospel and globalization : exploring the religious roots of a globalized world / edited by Michael W. Goheen and Erin G. Glanville. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-57383-440-7 1. Globalization—Religious aspects—Christianity. 2. Globalization— Religious aspects—Islam. 3. Capitalism—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Capitalism—Religious aspects—Islam. 5. Globalization—Moral and ethical aspects. 6. Globalization—Economic aspects. 7. Christian ethics. 8. World politics. I. Goheen, Michael W., 1955- II. Glanville, Erin G., 1980- BL65.G55G68 2009 201’.7 C2009-902767-4 For Phoebe Shalom, because the future is secure Table of Contents Preface 7 Introduction 11 Michael W. Goheen and Erin G. -

Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement

SEED WORKING PAPER No. 30 Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement by Andy Redfern and Paul Snedker InFocus Programme on Boosting Employment through Small EnterprisE Development Job Creation and Enterprise Department International Labour Office · Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2002 First published 2002 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; e-mail: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; e-mail: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ILO Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement Geneva, International Labour Office, 2002 ISBN 92-2-113453-9 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Fair Trade 1 Fair Trade

Fair trade 1 Fair trade For other uses, see Fair trade (disambiguation). Part of the Politics series on Progressivism Ideas • Idea of Progress • Scientific progress • Social progress • Economic development • Technological change • Linear history History • Enlightenment • Industrial revolution • Modernity • Politics portal • v • t [1] • e Fair trade is an organized social movement that aims to help producers in developing countries to make better trading conditions and promote sustainability. It advocates the payment of a higher price to exporters as well as higher social and environmental standards. It focuses in particular on exports from developing countries to developed countries, most notably handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, bananas, honey, cotton, wine,[2] fresh fruit, chocolate, flowers, and gold.[3] Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect that seek greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. Fair Trade Organizations, backed by consumers, are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.[4] There are several recognized Fairtrade certifiers, including Fairtrade International (formerly called FLO/Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International), IMO and Eco-Social. Additionally, Fair Trade USA, formerly a licensing -

What Is Fair Trade?

What is Fair Trade? . A system of exchange that honors producers, communities, consumers and the environment. A model for the global economy rooted in people-to-people connections, justice and sustainability. A commitment to building long-term relationships between producers and consumers. A way of life! Fair Trade - Criteria . Paying a fair wage . Giving employees opportunities for advancement . Providing equal employment opportunities for all people, particularly the most disadvantaged . Engaging in environmentally sustainable practices Fair Trade - Criteria . Being open to public accountability . Building sustainable long-term trade relationships . Providing healthy and safe working conditions . Providing financial and technical assistance to producers whenever possible What does the Fair Trade label look like? What does the Fair Trade label mean? Fair Price Democratically organized groups receive a minimum floor price and an additional premium for certified organic agricultural products. Farmer organizations are also eligible for pre-harvest credit. Artisan groups and cooperatives receive a fair living wage for the time it takes to make a product. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Fair Labor Conditions Workers on fair trade farms and other environments enjoy freedom of association, safe working conditions, and living wages. Forced child labor is strictly prohibited. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Direct trade Importers purchase from Fair Trade producer groups as directly as possible, eliminating unnecessary middlepersons and empowering farmers and others to develop the business capacity needed to compete in the global marketplace. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Democratic and transparent organizations Workers decide democratically how to invest Fair Trade revenues. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Environmental Sustainability Harmful agrochemicals and GMOs are strictly prohibited in favor of environmentally sustainable farming methods that protect farmers’ health and preserve valuable ecosystems for future generations. -

Fair Trade: Social Regulation in Global Food Markets

Journal of Rural Studies 28 (2012) 276e287 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Rural Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jrurstud Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets Laura T. Raynolds* Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Sociology Department, Clark Building, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, United States abstract Keywords: This article analyzes the theoretical and empirical parameters of social regulation in contemporary global Regulation food markets, focusing on the rapidly expanding Fair Trade initiative. Fair Trade seeks to transform Globalization North/South relations by fostering ethical consumption, producer empowerment, and certified Fair Trade commodity sales. This initiative joins an array of labor and environmental standard and certification Certification systems which are often conceptualized as “private regulations” since they depend on the voluntary participation of firms. I argue that these new institutional arrangements are better understood as “social regulations” since they operate beyond the traditional bounds of private and public (corporate and state) domains and are animated by individual and collective actors. In the case of Fair Trade, I illuminate how relational and civic values are embedded in economic practices and institutions and how new quality assessments are promoted as much by social movement groups and loosely aligned consumers and producers as they are by market forces. This initiative’s recent commercial success has deepened price competition and buyer control and eroded its traditional peasant base, yet it has simultaneously created new openings for progressive politics. The study reveals the complex and contested nature of social regulation in the global food market as movement efforts move beyond critique to institution building. -

Devolution, Nation-Building and Development Assistance

Devolution, Nation-Building and Development Assistance: A Case Study of the Welsh Government’s Wales for Africa Programme Kathleen Mulready This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography and Planning Cardiff University 2017 Abstract Devolution, Nation-Building and Development Assistance A Case Study of the Welsh Government’s Wales for Africa programme Abstract This study explores Wales for Africa, the Welsh Government’s international development programme. It particularly considers the issues of political decentralisation, and participation in development assistance, on the making of national identity in contemporary Wales. Using a case study methodology, and a conceptual framework of the sub-state and the citizen as development actor, it explores how notions of Welsh subjectivity are tied to iterations of national identity and civic value, constructed around the concept of sustainable development, and ideas of mutual benefit and reciprocity in international development. It focuses specifically on community-based development organisations linked with partner organisations in sub- Saharan Africa. Although the potential benefits of citizen-led development initiatives to right-based approaches are recognised, little attention has previously been paid to the role of international development to sub-state nation-building. The study seeks to address this gap. Situated within the field of interpretive policy analysis, the thesis adopts a context sensitive approach focussed on how a political narrative around nationhood and civic value has been constructed around Wales’ development activities as a symbol of an alternative nation. Beginning with political devolution, the timeframe of the study ends at October 2016. -

Additional Information About the U.S. Economy, Top U.S. Imports, Sector Websites, and Consumer Good Marketing

Additional Information about the U.S. Economy, Top U.S. Imports, Sector Websites, and Consumer Good Marketing 1.) U.S. Economy (2007) • GDP - $13.78 Trillion • Population – 304 million • GDP – per capita - $45,800 people • GDP – composition by sector • Labor Force – 153.1 million o Services – 79% (including unemployed) o Agriculture – 1.2% • Exports - $1.148 trillion o Industry – 19.8% • Imports $1.968 trillion 2.) Top U.S. Imports (2007) Product Share (by %) 1) Mineral fuel, oil, etc. 18.7 14) Iron/Steel Products 1.62 2) Machinery 12.8 15) Toys And Sports Equipment 1.59 3) Electrical machinery 12.7 16) Iron And Steel 1.31 4) Auto, bus & truck vehicles 11.0 17) Aircraft, Spacecraft 1.12 5) Computers & telephones 2.75 18) Salvaged & recycled goods 1.08 6) Pharmaceutical products 2.50 19) Footwear 0.99 7) Precious stones, metals 2.43 20) Rubber 0.96 8) Organic chemicals 2.31 TOTAL 100.0 9) Furniture and bedding 2.09 10) Auto parts 2.01 Source: U.S. Department of 11) Knit Apparel 1.94 Commerce, Bureau of Census 12) Woven Apparel 1.92 13) Plastic 1.76 3.) Sector-Specific Contact Information for Standards and Regulations a. Textiles and Apparel http://web.ita.doc.gov/tacgi/labeling2.nsf/ http://web.ita.doc.gov/tacgi/eamain.nsf/6e1600e39721316c852570ab0056f719/448cd661f6 48520c8525739a005a725a?OpenDocument b. Mining/Marble: National Mining Association: http://www.nma.org/ Contacts: Moya Phelleps Senior Vice President, Member Services Emily Schlect International Policy Analyst c. Jewelry: http://www.ita.doc.gov/td/ocg/jewelry.htm 1 d. -

Bringing Quality to Life

CAFÉDIRECT PLC ANNUAL REPORT OCTOber 2006 – September 2007 BRINGING QUALITY TO LIFE chairman’s message Welcome to our Annual Report for 2006/07 Last year I mentioned we were strengthening our foundations and I’m pleased to say the results of this have shown through very positively. Despite ever increasing competition, the business is more profitable and there has been a modest improvement in UK sales. We have continued to provide a strong social return and as a result of high quality financial and supply chain management, our cash balance is much healthier. The social return has meant further investment in our Producer Partnership Programme (PPP), benefiting our growers, their businesses, and their communities. Our increase in profits and cash has meant greater reserves to withstand any turmoil in the world markets that might affect us. CAFÉDIRECT PLC 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2006/07 There has also been solid progress on Cafédirect and the world of Fairtrade, developing sales into new markets in Asia. and further wish her the very best in all However, we have not yet embarked on her future endeavours. the expansion ideas that I previewed with Following a thorough and extensive you at the AGM last year. There are two search for her successor, I am also very reasons for this postponement. Firstly, it was pleased to announce that Anne MacCaig apparent at the last AGM that support for a has been appointed, and will be joining significant expansion was divided amongst us as our new CEO from 11 March 2008. shareholders, both very positive and very Anne has over 20 years of experience in negative. -

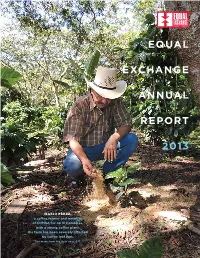

Equal Exchange Annual Report 2013

EQUAL EXCHANGE ANNUAL REPORT 2013 mario pÉrez, a coffee farmer and member of COMSA Co-op in Honduras, with a young coffee plant. His farm has been severely affected by coffee leaf rust. See more from the field on p. 6-7. “WE HAVE BEEN LEADERS IN THIS FIGHT. AND WE HAVE HAD SOME SUCCESSES AND SOME FAILURES. WE HAVE HAD LOTS OF CHALLENGES, BUT YOU WILL NEVER HAVE PROOF OF YOUR SUCCESS IF YOU DON’T TRY.” Margarito Lucas Miguel, below left, a member of Flor del Café Co-op in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala ii From the Office of the Executive Directors Check it Out Through our Charitable Contributions we gave away a portion of pre-tax profits to allied organizations like Fair World Project, Red Tomato, and the InterReligious Task Onwards Force on Central America. & Upwards By Rob Everts & Rink Dickinson, Co-Executive Directors Expansion in products, alliances and geography drove much of our work and increased sales in 2013. On sales of $56.1 million, after charitable contributions and worker-owner patronage disbursements, we realized net income before taxes of $2.7 million. We tried to match the urgent need for markets of small-scale farmers with products that our loyal base of OUR MISSION accounts could competitively offer their customers. Organic To build long-term trade partnerships that are economically just and environmentally sound, cashews from India and El Salvador, organic mangos from to foster mutually beneficial relationships between Burkina Faso, and flame raisins from Chile were among those farmers and consumers and to demonstrate, through our success, that reached store shelves and congregations in 2013. -

Can Scotland Still Call Itself a Fair Trade Nation?

Can Scotland still call itself a Fair Trade Nation? A report by the Scottish Fair Trade Forum JANUARY 2017 CAN SCOTLAND STILL CALL ITSELF A FAIR TRADE NATION? Scottish Fair Trade Forum Robertson House 152 Bath Street Glasgow G2 4TB +44 (0)141 3535611 www.sftf.org.uk www.facebook.com/FairTradeNation www.twitter.com/FairTradeNation [email protected] Scottish charity number SC039883 Scottish registered company number SC337384. Acknowledgements The Scottish Fair Trade Forum is very grateful for the help and advice received during the preparation of this report. We would like to thank everyone who has surveys and those who directly responded been involved, especially the Assessment to our personalised questionnaires: Andrew Panel members, Patrick Boase (social auditor Ashcroft (Koolskools Founding Partner), registered with the Social Audit Network UK Amisha Bhattarai (representative of Get Paper who chaired the Assessment Panel), Dr Mark Industry – GPI, Nepal), Mandira Bhattarai Hayes (Honorary Fellow in the Department of (representative of Get Paper Industry – GPI, Theology and Religion at Durham University, Nepal), Rudi Dalvai (President of the World Chair of the WFTO Appeals Panel and Fair Trade Organisation – WFTO), Patricia principal founder of Shared Interest), Penny Ferguson (Former Convener of the Cross Newman OBE (former CEO of Cafédirect and Party Group on Fair Trade in the Scottish currently a Trustee of Cafédirect Producers’ Parliament), Elen Jones (National Coordinator Foundation and Drinkaware), Sir Geoff Palmer at Fair Trade Wales), -

Fairtrade County Borough Status

MERTHYR TYDFIL COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL Civic Centre, Castle Street, Merthyr Tydfil, CF47 8AN Main Tel: 01685 725000 www.merthyr.gov.uk CABINET REPORT Date Written 12 th May 2011 Report Author Alyn Owen Service Area Customer Services Committee Division Cabinet Committee Date 12 th October 2011 To: Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen Fairtrade County Borough Status PURPOSE OF THE REPORT: To update Cabinet on progress in implementing the Fairtrade Initiative within the town centre and to seek approval to extend this to the wider County Borough area. The report also seeks approval to amend the current LA franking machine to include a postage mark reflecting Merthyr Tydfil’s Fair Trade status and to consider a request to only provide Fairtrade products for sale in all Council run outlets 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1 On 28 th July 2008, Cabinet agreed to build on the successful Fairtrade Town campaign by approving the development of the Fairtrade County Borough Initiative. 2.0 IMPLEMENTATION 2.1 On 9 th November 2009, Merthyr Tydfil County Borough achieved Fairtrade County status. In achieving this status the Local Authority had implement five objectives developed by Fair Trade Wales in agreement with the Welsh Assembly Government, the Scottish Government, and the Scottish Fair Trade Forum in consultation with the Fairtrade Foundation. The status was renewed for a year on February 28 th 2011 2.2 The five objectives were: • The Council to pass a resolution to support Fairtrade, committing to serve Fairtrade coffee and tea at its meetings, offices and any food outlets. • A range of Fairtrade products is readily available in shops across the County Borough. -

Kongressprogramm Congress Programme

BioFach 2012 Vivaness AKTUELLE VERSION UPDATED VERSION Kongressprogramm Congress programme 15. – 18. Februar 2012 | 15 – 18 February 2012 BioFach Vivaness | kongress | congress Ebenenübersicht NCC Ost Plan of floors NCC Ost NCC Mitte Halle 9 | Hall 9 BioFach • Vivaness 2012 | Seite | page 2 Vorträge in Deutsch / Seminars in German Seminars in English / Vorträge in Englisch inhalt | content foren | forums 4 – 5 | Nachhaltigkeits Forum | Sustainability Forum Wie kann Nach- haltigkeit gemessen und verständlich vermittelt werden? How can sustainability be measured and communicated in an understandable way? 6 – 7 | Fachhandels Forum Wie kann sich der Fachhandel weiter etablieren? Wie können Händler Kunden binden und neue gewinnen? How to establish the position of specialised organic retail and how to win customers? 8 – 9 | Vivaness Forum Wie können sich Kosmetikhersteller differenzieren? Wie entwickelt sich der Markt? How can cosmetic manufacturers distinguish themselves from the competition? How is the market developing? 10 | oGrastro F um | HoReCa Forum Welche Rolle spielt Nachhaltigkeit in der Gastronomie? Wie kann die Wirtschaftlichkeit gewährleistet werden? What role does sustainability play? How can profitability be ensured? 11 | Fair Forum Wie können sich Fair Trade und Bio gegenseitig stützen? Was sind gemeinsame Ziele und Strategien? How can fair trade and organic support each other? What joint goals and strategies are there? 12 | Textil Forum | Textile Forum Wie können Handelskanäle weiter aus- gebaut werden? Welchen Fasern gehört die Zukunft? How can the trading channels be further developed? What fibres will be the future hits? 13 | Wein Forum | Wine Forum Wie wichtig werden neue Aspekte im Weinbau? Wie entwickelt sich der Markt national und international? How important are new aspects in winegrowing? How is the market developing nationally and internationally? programm | programme 14 – 30 | Alle Details | Full details Termine, Inhalte, Referenten.