Report on the Second KIMS-CNA Conference: “The PLA Navy's Build

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sailors Aboard the USS Cole Tell Their Stories

Sailors aboard the USS Cole tell their stories Adapted from the broadcast audio segment; use the audio player to listen to the story in its entirety. Master Chief Petty Officer Pamela Jacobsen: “The first thing I remember about that morning going aloft was it was really hot. I don’t know how people live there and stand the heat. I knew I didn’t want to stay up there too long. I remember seeing the port like a place that was carved out of a piece of sand to me.” Lieutenant JG Robert Overturf: “We got there before sunrise. There was this field littered with sunken ships. Destruction all over. To think that we were going to pull into that [port] to refuel was a little bit odd.” Kirk Lippold, Commanding Officer of USS Cole: “I think everybody realized that there was an elevated threat level. But when we pulled in, there was no evidence of a specific threat for that port or for our ship. Shortly after 10:30am, we started refueling the ship and it was routine.” Lt. Elroy Newton: “I went down to the oil lab to take station, and my boss told me, ‘Hey, Chief, you were down here the last two times. Go top side and I will go ahead and take the oil lab.’ So that’s what he did. I headed topside. I took the headset and then we were kind of joking back and forth a little bit. About two minutes after that is when we felt and heard a huge explosion. -

China's Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations

China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations The modular transfer system between a Type 054A frigate and a COSCO container ship during China’s first military-civil UNREP. Source: “重大突破!民船为海军水面舰艇实施干货补给 [Breakthrough! Civil Ships Implement Dry Cargo Supply for Naval Surface Ships],” Guancha, November 15, 2019 Primary author: Chad Peltier Supporting analysts: Tate Nurkin and Sean O’Connor Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. 1 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology, Scope, and Study Limitations ........................................................................................................ 6 1. China’s Expeditionary Operations -

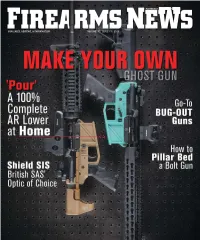

FIREARMS NEWS - Firearmsnews.Com VOLUME 70 - ISSUE 13

FORMERLY GUN SALES, REVIEWS, & INFORMATION VOLUME 70 | ISSUE 13 | 2016 PAGE 2 FIREARMS NEWS - firearmsnews.com VOLUME 70 - ISSUE 13 TM KeyMod™ is the tactical KeyMod is here! industry’s new modular standard! • Trijicon AccuPoint TR24G 1-4x24 Riflescope $1,020.00 • American Defense • BCM® Diamondhead RECON X Scope ® Folding Front Sight $99.00 • BCM Diamondhead Mount $189.95 Folding Rear Sight $119.00 • BCM® KMR-A15 KeyMod Rail • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ Handguard 15 Inch $199.95 Compensator Mod 0 $89.95 • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ ® BCMGUNFIGHTER™ KMSM • BCM Low Profile QD End Plate $16.95 • KeyMod QD Sling Mount $17.95 Gas Block $44.95 • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ Stock $55.95 Vertical Grip Mod 3 $18.95 GEARWARD Ranger • ® Band 20-Pak $10.00 BCM A2X Flash • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ Suppressor $34.95 Grip Mod 0 $29.95 B5 Systems BCMGUNFIGHTER™ SOPMOD KeyMod 1-Inch Bravo Stock $58.00 Ring Light BCM® KMR-A Mount KeyMod Free Float For 1” diameter Rail Handguards lights $39.95 Blue Force Gear Same as the fantastic original KMR Handguards but machined from aircraft aluminum! BCMGUNFIGHTER™ VCAS Sling $45.00 BCM 9 Inch KMR-A9 . $176.95 KeyMod Modular BCM 10 Inch KMR-A10 . $179.95 BCM 13 Inch KMR-A13 . $189.95 Scout Light Mount BCM 15 Inch KMR-A15 . $199.95 For SureFire Scout BCM® PNT™ Light $39.95 Trigger Assembly Polished – Nickel – Teflon BCMGUNFIGHTER™ $59.95 KeyMod Modular PWS DI KeyMod Rail Handguard Light Mount Free float KeyMod rail for AR15/M4 pattern rifles. For 1913 mounted Wilson PWS DI 12 Inch Rail . $249.95 lights $39.95 Combat PWS DI 15 Inch Rail . -

PDF Download — Black & White Version

MANAGING THE GLOBAL IMPACT TO ASIA Charles M. Perry Bobby Andersen Published by The Institute for Foreign Policy Analysis MANAGING THE GLOBAL IMPACT TO ASIA Charles M. Perry Bobby Andersen December 2014 Published by The Institute for Foreign Policy Analysis Contents Chapter One Introduction 1 Chapter Two The Pivot in Review 10 The Rationale for the Pivot and Its Policy Roots 11 Update on the Pivot’s Progress 23 The FY 2015 Budget, the QDR, Russia, and 47 Other Potential Complications Conclusion 62 Chapter Three European Views on the Pivot and Asian Security 65 European Economic and Strategic Interests in Asia 71 European Schools of Thought on Asian Security 84 and the Rebalance European Security Concerns Regarding 108 the Asia-Pacific Region Possible New Roles for Europe in Asia-Pacific Security 118 Russian Reponses to the Rebalance 129 Conclusion 138 Chapter Four Security Trends in Other Key Regions and 142 Their Implications for the Pivot Security Trends and Developments in the Middle East 143 Security Trends and Developments in Africa 177 Security Trends and Developments in Latin America 190 Conclusion 200 iii Managing the Global Impact of America’s Rebalance to Asia Chapter Five Conclusions and Recommendations 202 Acknowledgments 215 About the Authors 217 iv Chapter One Introduction SOME THREE YEARS after President Obama announced in a November 2011 speech to the Australian parliament that he had made a “deliberate and strategic decision” for the United States to “play a larger and long-term role in shaping [the Asia-Pacific] region” and to make the U.S. “presence and mission in the Asia-Pacific a top priority,”1 the Pacific “pivot,” as it was initially dubbed, remains very much a work in progress. -

Crossing the Atlantic War Wrecks El Hierro Patrick Chevailler

Skin & Hair Care for Divers Adventure Crossing the Atlantic Palau GLOBAL EDITION June :: July War Wrecks 2006 Number 11 Canary Islands El Hierro Portfolio Patrick Chevailler Ecology Global Warming Can Corals Adapt? ARGENTINA Great Conveyor Belt Patagonia Creating Reefs in COVER PHOTO BY MARCELO MAMMANA the Maldives 1 X-RAY MAG : 11 : 2006 DIRECTORY X-RAY MAG is published by AquaScope Underwater Photography Divers’ Costmetics Copenhagen, Denmark - www.aquascope.biz www.xray-mag.com Skin & Hair Care for Divers... page 67 ALOE GATOR LIP BALM IN SEVERAL FLAVOURS AVAILABLE FROM WWW.ALOEGATOR.COM PUBLISHER CO- EDITORS & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Andrey Bizyukin Peter Symes Delicate Sea Anemone, Patagonia, Argentina. Photo by Marcelo Mammana - Caving, Equipment, Medicine [email protected] Millis Keegan MANAGING EDITOR - Opinions and ‘DiveGuru.net’ contents & CREATIVE DIRECTOR Michael Arvedlund - Ecology Gunild Pak Symes Jason Heller - Photography [email protected] Dan Beecham - videography ADVERTISING Michel Tagliati - Medicine Americas & United Kingdom: Leigh Cunningham Kevin Brennan - Technical Diving [email protected] Edwin Marcow Europe & Africa: - Sharks, Adventures Harvey Page, Michael Portelly [email protected] Catherine GS Lim International sales manager: Arnold Weisz Arnold Weisz [email protected] REGULAR WRITERS Robert Aston - CA, USA South East Asia Rep: Bill Becher - CA, USA Catherine GS Lim, Singapore [email protected] John Collins - Ireland Amos Nachoum - CA, USA Internet Advertising: Nonoy Tan - The Philippines Deb Fugitt, USA [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS THIS ISSUE SENIOR EDITOR Michael Arvedlund, PhD Michael Symes Dan Beecham [email protected] Andrey Bizyukin, PhD Eric Cheng TECHNICAL MANAGER Patrick Chevailler Søren Reinke [email protected] Leigh Cunningham Ethan Gordon CORRESPONDENTS Jason Heller Enrico Cappeletti - Italy Jerome Hingrat 25 33 39 45 50 plus.. -

The Bahamas and Florida Keys

THE MAGAZINE OF DIVERS ALERT NETWORK FALL 2014 A TASTE OF THE TROPICS – THE BAHAMAS AND FLORIDA KEYS THE UNDERWATER WILD OF CRISTIAN DIMITRIUS CULTURE OF DIVE SAFETY PROPELLER HAZARDS Alert_DS161.qxp_OG 8/29/14 11:44 AM Page 1 DS161 Lithium The Choice of Professionals Only a round flash tube and custom made powder-coated reflector can produce the even coverage and superior quality of light that professionals love. The first underwater strobe with a built-in LED video light and Lithium Ion battery technology, Ikelite's DS161 provides over 450 flashes per charge, instantaneous recycling, and neutral buoyancy for superior handling. The DS161 is a perfect match for any housing, any camera, anywhere there's water. Find an Authorized Ikelite Dealer at ikelite.com. alert ad layout.indd 1 9/4/14 8:29 AM THE MAGAZINE OF DIVERS ALERT NETWORK FALL 2014 Publisher Stephen Frink VISION Editorial Director Brian Harper Striving to make every dive accident- and Managing Editor Diana Palmer injury-free. DAN‘s vision is to be the most recognized and trusted organization worldwide Director of Manufacturing and Design Barry Berg in the fields of diver safety and emergency Art Director Kenny Boyer services, health, research and education by Art Associate Renee Rounds its members, instructors, supporters and the Graphic Designers Rick Melvin, Diana Palmer recreational diving community at large. Editor, AlertDiver.com Maureen Robbs Editorial Assistant Nicole Berland DAN Executive Team William M. Ziefle, President and CEO Panchabi Vaithiyanathan, COO and CIO DAN Department Managers Finance: Tammy Siegner MISSION Insurance: Robin Doles DAN helps divers in need of medical Marketing: Rachelle Deal emergency assistance and promotes dive Medical Services: Dan Nord safety through research, education, products Member Services: Jeff Johnson and services. -

Treatment of Pediatric Diaphyseal Femur Fractures Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline

TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC DIAPHYSEAL FEMUR FRACTURES EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Adopted by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors June 12, 2015 2015 REPORT FOR THE REISSUE OF THE 2009 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE ON THE TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC DIAPHYSEAL FEMUR FRACTURES “This guideline is greater than 5 years old and is reviewed every five years. New studies have been published since this guideline was developed, however the AAOS has determined that these studies are not sufficient to warrant changing the guideline at this time. The information contained in this guideline provides the user with the best evidence available at the time this guideline was published.” OVERVIEW OF 2015 UPDATES TO THE 2009 ORIGINAL GUIDELINE 1) Addition of the Shemshaki, et al, 2011 study findings to Elastic Intramedullary Nails. 2) Updated strength of recommendation language to match current AAOS guideline language (see Grading the Recommendations). 3) Removed “inconclusive” recommendations due to lack of evidence (see Appendix XI) For a user-friendly version of this clinical practice guideline, please visit the AAOS OrthoGuidelines Web-Based App at: http://www.orthoguidelines.org AAOS v 1.0 061909 Disclaimer This Clinical Practice Guideline was developed by an AAOS physician volunteer Work Group based on a systematic review of the current scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis. This Clinical Practice Guideline is not intended to be a fixed protocol, as some patients may require more or less treatment or different means of diagnosis. Clinical patients may not necessarily be the same as those found in a clinical trial. -

North Sulawesi One of Theworld's Topdive Spots

6.1 • Jan / Feb 07 • www.nsonline.com JAN / FEB 07 magazine NORTH SULAWESI NORTH SULAWESI KAVIENG KAVIENG CLOWNFISH CLOWNFISH DIVE DIARY DIVE DIARY RULE OF THIRDS OF RULE NoExplorert h Sulawesi one of theworld’s topdive spots KDN PPS 1625/5/2007 MICA (P) 153/11/2005 Cut your photos in 3 Introducing Dive Diary Meet the Real Nemo The Cutting Edge Learn about the Rule of Thirds The Challenge: Chapter 1 Everyone’s favourite cuddly Have you got what it takes clowns of the reef to dive a rebreather? 6.1 60 46 42 52 9 770219 683011 Australia A$7.60 (incl GST) • Brunei B$7.00 • Hong Kong HK$46 • Indonesia Rp 40,000 • Malaysia RM14 • Maldives MVR110 ISSN 0219-6832 New Zealand NZ$ 7.50 (incl GST) • PNG K6.90 • Philippines P150 • Singapore S$7.00 (incl GST) • Taiwan NT$140 • Thailand Bht180 62 FEATURES 16 • NORTH SULAWESI Think Di erent Tony Wu and Jez Tryner 42 • CRITTERS Adorable Clowns of the Coral Andrea & Antonella Ferrari 46 • DIVE DIARY The Challenge: Chapter 1 The FiNS Team 62 • KAVIENG Just The Way It Should Be 16 Ange Hellberg PICTURE PERFECT 12 • SNAPSHOTS Labuan & Layang Layang Pipat Kosumlaksamee 38 • TALKING MEGAPIXELS Competitive Streak Dr. Alexander Mustard 54 • LENSCAPE Shades of Grey 52 Nat Sumanatemeya 60 • PIXTIPS & other topix The Rule of Thirds 46 Polpich Komson 80 • FINAL FRAME Nudibranch Mugshot Morakot Chuensuk Cover: Long-spine porcupinesh (Diodon holocanthus) peeking out from a discarded can in the Lembeh Strait in North Sulawesi, 54 Indonesia Tony Wu VOLUME 6.1 JANUARY / FEBRUARY ‘07 DEPARTMENTS 08 • GEAR HERE 14 • DIVE -

Naval Directory Singapore's Armed Forces Naval

VOLUME 25/ISSUE 3 MAY 2017 US$15 ASIA PAcific’s LARGEST CIRCULATED DEFENCE MAGAZINE NAVAL DIRECTORY SINGAPORE’S ARMED FORCES NAVAL HELICOPTERS SMALL ARMS/LIGHT WEAPONS CIWS MARITIME PATROL AIRCRAFT www.asianmilitaryreview.com One Source. Naval Force Multiplier. Seagull: From MCM to ASW, unmanned sea supremacy Elbit Systems’ synergistic technologies are now revolutionizing Unmanned Surface Vessels. Seagull delivers multi-mission power while protecting lives and reducing costs. Two organic USVs controlled by one Mission Control System (CMS), taking on the challenges of Mine Counter Measures (MCM) and Anti Submarine Warfare (ASW). Rule the waves with Elbit Systems’ new naval force multiplier. Visit us at IMDEX 2017 Stand #M22 02 | ASIAN MILITARY REVIEW | Contents MAY 2017 VOLUME 25 / ISSUE 3 Andrew White examines small arms and light weapons procurement in the Asia-Pacific and 14 finds international suppliers vying with local companies to satisfy emerging demands. Front Cover Photo: Close-in weapons systems provide vital protection for warships against anti-ship missiles and an expanding set of ENHANCING threats, as detailed in this issue’s Close Protection article. THE MISSION 20 36 46 52 Naval Starship Directory 2017 Feet Wet Enterprise AMR’s ever-popular Naval Close Protection Andrew Drwiega examines A space race is well underway in Directory returns with Gerrard Cowan explores the naval support helicopter the Asia-Pacific, with Dr. Alix Valenti at the helm, with improvements being rolled out procurement across the Asia- Beth Stevenson discussing updated naval orders-of-battle in the close-in weapons system Pacific, noting the preference the health of several space and programme information domain to protect warships for new, as well as upgraded, programmes in the region, and from across the region. -

UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER October 2011

OUR CREED: To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its constitution. UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER October 2011 1 Picture of the Month………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Meeting Attendees………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….5 Members…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Honorary Members……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 New Business…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Old Business….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Good of the Order……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Base Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Birthdays……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Welcome…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Binnacle List………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Quote of the Month.…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Dates in American Naval History……………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Dates in U.S. Submarine History………………………………………………………………………………………………16 Traditions of the Naval Service………………………………………………………………………………………………..44 Newsletter award…………………………………………………..……………………………………………………………….46 Monthly Calendar……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………47 Lost Boats...................................................................................................................................48 -

Tuesday December 5 4:50 PM ET Persian Gulf Security Increased by ROBERT BURNS, AP Military Writer WASHINGTON

Tuesday December 5 4:50 PM ET Persian Gulf Security Increased By ROBERT BURNS, AP Military Writer WASHINGTON (AP) - Defense Secretary William Cohen has authorized military commanders to send dozens of additional U.S. forces to the Persian Gulf to strengthen port security, Pentagon (news - web sites) officials said Tuesday. The move is part of a Pentagon effort to improve the protection of American ships and other military forces in the region in the aftermath of the Oct. 12 terrorist bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen. The Navy, meanwhile, said the heavily damaged Cole is due to arrive back in the United States next week. The Cole, which lost 17 sailors in the suicide bombing, has been in transit from the Middle East since early November aboard a Norwegian-owned heavy lift ship. It will be off-loaded at Ingalls Shipbuilding in Pascagoula, Miss., for repairs that are expected to take one year and cost roughly $240 million. A small boat maneuvered close to the Cole while it was refueling in Aden harbor and detonated a bomb that blew a hole in the ship's hull 40 feet wide and 40 feet high. Yemeni and American law enforcement authorities are still investigating the attack, for which no credible claim of responsibility has been made. The day the Cole was attacked, U.S. Navy commanders in the Middle East ordered all ships out of port and they have not returned since. Pentagon spokesman Rear Adm. Craig Quigley said Tuesday ``there is a great desire'' to ease the security restrictions ``to have a more comfortable and relaxed standard of living, if you will, for our sailors and marines in that area, and yet the first priority has to be force protection.'' To strengthen port security in the Gulf, Cohen authorized the deployment of extra Navy and Coast Guard security personnel, Quigley said. -

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS