PDF Download — Black & White Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6950/d-32-daring-type-45-batch-1-2015-harpoon-726950.webp)

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon United Kingdom Type: DDG - Guided Missile Destroyer Max Speed: 28 kt Commissioned: 2015 Length: 152.4 m Beam: 21.2 m Draft: 7.4 m Crew: 190 Displacement: 7450 t Displacement Full: 8000 t Propulsion: 2x Wärtsilä 12V200 Diesels, 2x Rolls-Royce WR-21 Gas Turbines, CODOG Sensors / EW: - Type 1045 Sampson MFR - Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 398.2 km - Type 2091 [MFS 7000] - Hull Sonar, Active/Passive, Hull Sonar, Active/Passive Search & Track, Max range: 29.6 km - Type 1047 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search & Navigation, Max range: 88.9 km - UAT-2.0 Sceptre XL - (Upgraded, Type 45) ESM, ELINT, Max range: 926 km - IRAS [CCD] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Visual, LLTV, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [IR] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Infrared, Infrared, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [Laser Rangefinder] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder, Max range: 0 km - Type 1046 VSR/LRR [S.1850M, BMD Mod] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 2000.2 km - Radamec 2500 [EO] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Visual, Visual, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification TV Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [IR] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Infrared, Infrared, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [Laser Rangefinder] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder for Weapon Director, Max range: 7.4 km - Type 1048 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search w/ OTH, Max range: 185.2 km Weapons / Loadouts: - Aster 30 PAAMS [GWS.45 Sea Viper] - Guided Weapon. -

The First Royal Navy Aircraft Carrier Deployment to the Indo-Pacific

NIDS Commentary No. 146 The first Royal Navy aircraft carrier deployment to the Indo-Pacific since 2013: Reminiscent of an untold story of Japan-UK defence cooperation NAGANUMA Kazumi, Planning and Management Division, Planning and Administration Department No. 146, 3 January 2021 Introduction: Anticipating the UK’s theatre-wide commitment to the Indo-Pacific in 2021 On 5 December, it was reported that the UK Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth would deploy to the Indo-Pacific region in early 2021 and conduct training with Japan and the US.1 It is the first time in the eight years since the disaster relief operations for the Philippines affected by typhoon in November 2013, that a Royal Navy aircraft carrier will deploy to the region. It is highly possible that the UK would clarify its theatre-wide commitment to the Indo-Pacific through the deployment of a brand-new aircraft carrier. According to a previous study on the UK’s military involvement in the region, for example, in Southeast Asia, “the development of security from 2010 to 2015 is limited” and “in reality, they conducted a patchy dispatch of their vessels when required for humanitarian assistance and search and rescue”.2 However, the study overlooked that in the context of disaster relief and search and rescue of missing aircrafts, considerably substantial defence cooperation has been already promoted between Japan and the UK, resulting in a huge impact on Japan’s defense policy. Coincidently, the year of 2021 is also the 100th anniversary of the Washington Conference which decided to renounce the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, so it will be a good opportunity to look at Japan-UK defence cooperation.3 The Japan-UK Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) came into effect on 1 January 2021. -

Report on the Second KIMS-CNA Conference: “The PLA Navy's Build

Report on the Second KIMS-CNA Conference: “The PLA Navy’s Build-up and ROK-USN Cooperation” Held in Seoul, Korea on 20 November 2008 Michael A. McDevitt CRM D0019742.A1/Final February 2009 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “problem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas: • The full range of Asian security issues • The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf • Maritime strategy • Insurgency and stabilization • Future national security environment and forces • European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral • West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea • Latin America • The world’s most important navies. -

Crossing the Atlantic War Wrecks El Hierro Patrick Chevailler

Skin & Hair Care for Divers Adventure Crossing the Atlantic Palau GLOBAL EDITION June :: July War Wrecks 2006 Number 11 Canary Islands El Hierro Portfolio Patrick Chevailler Ecology Global Warming Can Corals Adapt? ARGENTINA Great Conveyor Belt Patagonia Creating Reefs in COVER PHOTO BY MARCELO MAMMANA the Maldives 1 X-RAY MAG : 11 : 2006 DIRECTORY X-RAY MAG is published by AquaScope Underwater Photography Divers’ Costmetics Copenhagen, Denmark - www.aquascope.biz www.xray-mag.com Skin & Hair Care for Divers... page 67 ALOE GATOR LIP BALM IN SEVERAL FLAVOURS AVAILABLE FROM WWW.ALOEGATOR.COM PUBLISHER CO- EDITORS & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Andrey Bizyukin Peter Symes Delicate Sea Anemone, Patagonia, Argentina. Photo by Marcelo Mammana - Caving, Equipment, Medicine [email protected] Millis Keegan MANAGING EDITOR - Opinions and ‘DiveGuru.net’ contents & CREATIVE DIRECTOR Michael Arvedlund - Ecology Gunild Pak Symes Jason Heller - Photography [email protected] Dan Beecham - videography ADVERTISING Michel Tagliati - Medicine Americas & United Kingdom: Leigh Cunningham Kevin Brennan - Technical Diving [email protected] Edwin Marcow Europe & Africa: - Sharks, Adventures Harvey Page, Michael Portelly [email protected] Catherine GS Lim International sales manager: Arnold Weisz Arnold Weisz [email protected] REGULAR WRITERS Robert Aston - CA, USA South East Asia Rep: Bill Becher - CA, USA Catherine GS Lim, Singapore [email protected] John Collins - Ireland Amos Nachoum - CA, USA Internet Advertising: Nonoy Tan - The Philippines Deb Fugitt, USA [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS THIS ISSUE SENIOR EDITOR Michael Arvedlund, PhD Michael Symes Dan Beecham [email protected] Andrey Bizyukin, PhD Eric Cheng TECHNICAL MANAGER Patrick Chevailler Søren Reinke [email protected] Leigh Cunningham Ethan Gordon CORRESPONDENTS Jason Heller Enrico Cappeletti - Italy Jerome Hingrat 25 33 39 45 50 plus.. -

The Bahamas and Florida Keys

THE MAGAZINE OF DIVERS ALERT NETWORK FALL 2014 A TASTE OF THE TROPICS – THE BAHAMAS AND FLORIDA KEYS THE UNDERWATER WILD OF CRISTIAN DIMITRIUS CULTURE OF DIVE SAFETY PROPELLER HAZARDS Alert_DS161.qxp_OG 8/29/14 11:44 AM Page 1 DS161 Lithium The Choice of Professionals Only a round flash tube and custom made powder-coated reflector can produce the even coverage and superior quality of light that professionals love. The first underwater strobe with a built-in LED video light and Lithium Ion battery technology, Ikelite's DS161 provides over 450 flashes per charge, instantaneous recycling, and neutral buoyancy for superior handling. The DS161 is a perfect match for any housing, any camera, anywhere there's water. Find an Authorized Ikelite Dealer at ikelite.com. alert ad layout.indd 1 9/4/14 8:29 AM THE MAGAZINE OF DIVERS ALERT NETWORK FALL 2014 Publisher Stephen Frink VISION Editorial Director Brian Harper Striving to make every dive accident- and Managing Editor Diana Palmer injury-free. DAN‘s vision is to be the most recognized and trusted organization worldwide Director of Manufacturing and Design Barry Berg in the fields of diver safety and emergency Art Director Kenny Boyer services, health, research and education by Art Associate Renee Rounds its members, instructors, supporters and the Graphic Designers Rick Melvin, Diana Palmer recreational diving community at large. Editor, AlertDiver.com Maureen Robbs Editorial Assistant Nicole Berland DAN Executive Team William M. Ziefle, President and CEO Panchabi Vaithiyanathan, COO and CIO DAN Department Managers Finance: Tammy Siegner MISSION Insurance: Robin Doles DAN helps divers in need of medical Marketing: Rachelle Deal emergency assistance and promotes dive Medical Services: Dan Nord safety through research, education, products Member Services: Jeff Johnson and services. -

Treatment of Pediatric Diaphyseal Femur Fractures Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline

TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC DIAPHYSEAL FEMUR FRACTURES EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Adopted by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors June 12, 2015 2015 REPORT FOR THE REISSUE OF THE 2009 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE ON THE TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC DIAPHYSEAL FEMUR FRACTURES “This guideline is greater than 5 years old and is reviewed every five years. New studies have been published since this guideline was developed, however the AAOS has determined that these studies are not sufficient to warrant changing the guideline at this time. The information contained in this guideline provides the user with the best evidence available at the time this guideline was published.” OVERVIEW OF 2015 UPDATES TO THE 2009 ORIGINAL GUIDELINE 1) Addition of the Shemshaki, et al, 2011 study findings to Elastic Intramedullary Nails. 2) Updated strength of recommendation language to match current AAOS guideline language (see Grading the Recommendations). 3) Removed “inconclusive” recommendations due to lack of evidence (see Appendix XI) For a user-friendly version of this clinical practice guideline, please visit the AAOS OrthoGuidelines Web-Based App at: http://www.orthoguidelines.org AAOS v 1.0 061909 Disclaimer This Clinical Practice Guideline was developed by an AAOS physician volunteer Work Group based on a systematic review of the current scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis. This Clinical Practice Guideline is not intended to be a fixed protocol, as some patients may require more or less treatment or different means of diagnosis. Clinical patients may not necessarily be the same as those found in a clinical trial. -

North Sulawesi One of Theworld's Topdive Spots

6.1 • Jan / Feb 07 • www.nsonline.com JAN / FEB 07 magazine NORTH SULAWESI NORTH SULAWESI KAVIENG KAVIENG CLOWNFISH CLOWNFISH DIVE DIARY DIVE DIARY RULE OF THIRDS OF RULE NoExplorert h Sulawesi one of theworld’s topdive spots KDN PPS 1625/5/2007 MICA (P) 153/11/2005 Cut your photos in 3 Introducing Dive Diary Meet the Real Nemo The Cutting Edge Learn about the Rule of Thirds The Challenge: Chapter 1 Everyone’s favourite cuddly Have you got what it takes clowns of the reef to dive a rebreather? 6.1 60 46 42 52 9 770219 683011 Australia A$7.60 (incl GST) • Brunei B$7.00 • Hong Kong HK$46 • Indonesia Rp 40,000 • Malaysia RM14 • Maldives MVR110 ISSN 0219-6832 New Zealand NZ$ 7.50 (incl GST) • PNG K6.90 • Philippines P150 • Singapore S$7.00 (incl GST) • Taiwan NT$140 • Thailand Bht180 62 FEATURES 16 • NORTH SULAWESI Think Di erent Tony Wu and Jez Tryner 42 • CRITTERS Adorable Clowns of the Coral Andrea & Antonella Ferrari 46 • DIVE DIARY The Challenge: Chapter 1 The FiNS Team 62 • KAVIENG Just The Way It Should Be 16 Ange Hellberg PICTURE PERFECT 12 • SNAPSHOTS Labuan & Layang Layang Pipat Kosumlaksamee 38 • TALKING MEGAPIXELS Competitive Streak Dr. Alexander Mustard 54 • LENSCAPE Shades of Grey 52 Nat Sumanatemeya 60 • PIXTIPS & other topix The Rule of Thirds 46 Polpich Komson 80 • FINAL FRAME Nudibranch Mugshot Morakot Chuensuk Cover: Long-spine porcupinesh (Diodon holocanthus) peeking out from a discarded can in the Lembeh Strait in North Sulawesi, 54 Indonesia Tony Wu VOLUME 6.1 JANUARY / FEBRUARY ‘07 DEPARTMENTS 08 • GEAR HERE 14 • DIVE -

Model Ship Book 4Th Issue

A GUIDE TO 1/1200 AND 1/1250 WATERLINE MODEL SHIPS i CONTENTS FOREWARD TO THE 5TH ISSUE 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Aim and Acknowledgements 2 The UK Scene 2 Overseas 3 Collecting 3 Sources of Information 4 Camouflage 4 List of Manufacturers 5 CHAPTER 2 UNITED KINGDOM MANUFACTURERS 7 BASSETT-LOWKE 7 BROADWATER 7 CAP AERO 7 CLEARWATER 7 CLYDESIDE 7 COASTLINES 8 CONNOLLY 8 CRUISE LINE MODELS 9 DEEP “C”/ATHELSTAN 9 ENSIGN 9 FIGUREHEAD 9 FLEETLINE 9 GORKY 10 GWYLAN 10 HORNBY MINIC (ROVEX) 11 LEICESTER MICROMODELS 11 LEN JORDAN MODELS 11 MB MODELS 12 MARINE ARTISTS MODELS 12 MOUNTFORD METAL MINIATURES 12 NAVWAR 13 NELSON 13 NEMINE/LLYN 13 OCEANIC 13 PEDESTAL 14 SANTA ROSA SHIPS 14 SEA-VEE 16 SANVAN 17 SKYTREX/MERCATOR 17 Mercator (and Atlantic) 19 SOLENT 21 TRIANG 21 TRIANG MINIC SHIPS LIMITED 22 ii WASS-LINE 24 WMS (Wirral Miniature Ships) 24 CHAPTER 3 CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURERS 26 Major Manufacturers 26 ALBATROS 26 ARGONAUT 27 RN Models in the Original Series 27 RN Models in the Current Series 27 USN Models in the Current Series 27 ARGOS 28 CM 28 DELPHIN 30 “G” (the models of Georg Grzybowski) 31 HAI 32 HANSA 33 NAVIS/NEPTUN (and Copy) 34 NAVIS WARSHIPS 34 Austro-Hungarian Navy 34 Brazilian Navy 34 Royal Navy 34 French Navy 35 Italian Navy 35 Imperial Japanese Navy 35 Imperial German Navy (& Reichmarine) 35 Russian Navy 36 Swedish Navy 36 United States Navy 36 NEPTUN 37 German Navy (Kriegsmarine) 37 British Royal Navy 37 Imperial Japanese Navy 38 United States Navy 38 French, Italian and Soviet Navies 38 Aircraft Models 38 Checklist – RN & -

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS -

X-Ray Magazine :: Issue 35 :: April 2010

Sea Glass Jewelry: Recycling Ocean Gems Mexico Cozumel Tech Talk GLOBAL EDITION Choosing a April 2010 Number 35 Tech Instructor Profile Rich Walker Wrecks Treasure Canary Islands Stingrays DOMINICA Hot Rod Sea Sculpture Cris Woloszak Sperm1 X-RAY MAG : 35 : 2010 Whales COVER PHOTO BY ERIC CHENG DIRECTORY X-RAY MAG is published by AquaScope Media ApS Frederiksberg, Denmark www.xray-mag.com PUBLISHER SENIOR EDITOR Interior of wreck, Scapa Flow, Scotland. Photo by Lawson Wood & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Symes Peter Symes [email protected] [email protected] SECTION EDITORS contents PUBLISHER / EDITOR Andrey Bizyukin, PhD - Features & CREATIVE DIRECTOR Arnold Weisz - News, Features Gunild Symes Catherine Lim - News, Books [email protected] Simon Kong - News, Books Mathias Carvalho - Wrecks ASSOCIATE EDITORS Cindy Ross - GirlDiver & REPRESENTATIVES: Cedric Verdier - Tech Talk Americas: Scott Bennett - Photography Arnold Weisz Scott Bennett - Travel [email protected] Fiona Ayerst - Sharks Michael Arvedlund, PhD Russia Editors & Reps: - Ecology Andrey Bizyukin PhD, Moscow [email protected] CORRESPONDENTS Robert Aston - CA, USA Svetlana Murashkina PhD, Moscow Enrico Cappeletti - Italy [email protected] John Collins - Ireland Marcelo Mammana - Argentina South East Asia Editor & Rep: Nonoy Tan - The Philippines Catherine GS Lim, Singapore [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS THIS ISSUE Ron Akeson ASSISTANT EDITORS Scott Bennett & REPRESENTATIVES: Mary Beth Beuke Malaysia Editor & Rep: Nick Bostic Simon Kong, Kuala Lumpur Mathias Carvalho [email protected] Eric Cheng Catherine GS Lim Canada/PNW Editor & Rep: Gareth Lock Barb Roy, Vancouver Rosemary E. Lunn [email protected] Bonnie McKenna Andy Murch GirlDiver Editor & PNW Rep: Barb Roy Cindy Ross, Tacoma, USA Robert Sterner [email protected] Gunild Symes ERIC CHENG Peter Symes ADVERTISING Carol Tedesco International sales rep: Chris Wolosjak Arnold Weisz Lawson Wood 24 30 36 53 plus.. -

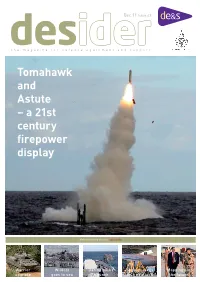

Tomahawk and Astute – a 21St Century Firepower Display

Dec 11 Issue 43 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Tomahawk and Astute – a 21st century firepower display Virtual warfare in focus See inside Warrior Wildcat Daring packs Support takes Mapping out upgrade goes to sea a punch on a new look the future FEATURES 6 24 Warfare staff go to war The Royal Navy has unveiled its new Maritime Composite Training System to a fanfare of trumpets and applause, marking the most radical change to its training for more than 40 years. 26 It’s the Army’s PlayStation generation Members of the British Army's PlayStation generation head to Helmand Province on the latest Operation Herrick deployment having honed their soldiering skills in virtual combat 28 Kestrel reaches full flight Project Kestrel – Information Systems and Services' reliable backbone communications network – is now complete, guaranteeing increased capacity and improved quality of communications in Afghanistan 2011 30 Defence Secretary praises ‘dedicated people’ New Defence Secretary Philip Hammond has praised 'the cover image most dedicated people in the public service' as he outlined A Tomahawk land attack missile is pictured being his vision for defence in his first public speech since fired byHMS Astute during her latest set of trials. The succeeding Dr Liam Fox missile, one of two fired on the trial, demonstrated complex evasive manoeuvres during flight and hit its designated target on a missile range DECEMBER desider NEWS Assistant Head, Public Relations: Ralph Dunn - 9352 30257 or 0117 9130257 5 Warrior in £1 billion -

JFQ 55 FORUM | Options for U.S.-Russian Strategic Arms Reductions

Issue 55, 4th Quarter 2009 New Journal from NDU Press PRISM JFQ National Defense University (NDU) is pleased to introduce PRISM, a complex operations journal. PRISM will explore, promote, and debate emerging thought and best practices as civilian capacity increases in operations in order to address challenges in stability, reconstruction, security, coun- terinsurgency, and irregular warfare. PRISM complements Joint Force Quarterly, introduced by General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 16 years ago to similarly advance joint force integration and understanding. PRISM welcomes articles on a broad range of complex operations issues, especially those that focus on the nexus of civil-military integration. The journal will be published four times a year both online and in hardcopy. It will debut in December 2009. Manuscripts submitted to PRISM should be between 2,500 and 6,000 words in length and sent via email to [email protected]. Call for Entries for the 2010 JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Secretary of Defense National Security Essay Competition and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Essay Competition Are you a Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) stu- process early and avoid the end-of-academic-year rush that dent? Imagine your winning essay in the pages of a future issue typically occurs each spring. JPME colleges are free to run their of Joint Force Quarterly. In addition, imagine a chance to catch own internal competitions to select nominees but must meet the ear of the Secretary of Defense or the Chairman of the Joint these deadlines: Chiefs of Staff on an important national security issue; recogni- tion by peers and monetary prizes await the winners.