Exploring the Colonial History of New Mexico Through Artifacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Bartolomé De Las Casas, Soldiers of Fortune, And

HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Dissertation Submitted To The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Damian Matthew Costello UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Dr. William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Dr. Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________ Dr. Roberto S. Goizueta, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation - a postcolonial re-examination of Bartolomé de las Casas, the 16th century Spanish priest often called “The Protector of the Indians” - is a conversation between three primary components: a biography of Las Casas, an interdisciplinary history of the conquest of the Americas and early Latin America, and an analysis of the Spanish debate over the morality of Spanish colonialism. The work adds two new theses to the scholarship of Las Casas: a reassessment of the process of Spanish expansion and the nature of Las Casas’s opposition to it. The first thesis challenges the dominant paradigm of 16th century Spanish colonialism, which tends to explain conquest as the result of perceived religious and racial difference; that is, Spanish conquistadors turned to military force as a means of imposing Spanish civilization and Christianity on heathen Indians. -

On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications American Studies 2008 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_fsp Recommended Citation Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26-56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the American Studies at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26–56. 0010-4175/08 $15.00 # 2008 Society for Comparative Study of Society and History DOI: 10.1017/S0010417508000042 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of “Underdevelopment” ALYOSHA GOLDSTEIN American Studies, University of New Mexico In 1962, the recently established Peace Corps announced plans for an intensive field training initiative that would acclimate the agency’s burgeoning multitude of volunteers to the conditions of poverty in “underdeveloped” countries and immerse them in “foreign” cultures ostensibly similar to where they would be later stationed. This training was designed to be “as realistic as possible, to give volunteers a ‘feel’ of the situation they will face.” With this purpose in mind, the Second Annual Report of the Peace Corps recounted, “Trainees bound for social work in Colombian city slums were given on-the-job training in New York City’s Spanish Harlem... -

State of Ambiguity: Civic Life and Culture in Cuba's First Republic

STATE OF AMBIGUITY STATE OF AMBIGUITY CiviC Life and CuLture in Cuba’s first repubLiC STEVEN PALMER, JOSÉ ANTONIO PIQUERAS, and AMPARO SÁNCHEZ COBOS, editors Duke university press 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data State of ambiguity : civic life and culture in Cuba’s first republic / Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos, editors. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5630-1 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5638-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba—History—20th century. 3. Cuba—Politics and government—19th century. 4. Cuba—Politics and government—20th century. 5. Cuba— Civilization—19th century. 6. Cuba—Civilization—20th century. i. Palmer, Steven Paul. ii. Piqueras Arenas, José A. (José Antonio). iii. Sánchez Cobos, Amparo. f1784.s73 2014 972.91′05—dc23 2013048700 CONTENTS Introduction: Revisiting Cuba’s First Republic | 1 Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos 1. A Sunken Ship, a Bronze Eagle, and the Politics of Memory: The “Social Life” of the USS Maine in Cuba (1898–1961) | 22 Marial Iglesias Utset 2. Shifting Sands of Cuban Science, 1875–1933 | 54 Steven Palmer 3. Race, Labor, and Citizenship in Cuba: A View from the Sugar District of Cienfuegos, 1886–1909 | 82 Rebecca J. Scott 4. Slaughterhouses and Milk Consumption in the “Sick Republic”: Socio- Environmental Change and Sanitary Technology in Havana, 1890–1925 | 121 Reinaldo Funes Monzote 5. -

The Last Conquistador” a Film by John J

Delve Deeper into “The Last Conquistador” A film by John J. Valadez & Cristina Ibarra This multi-media resource list, John, Elizabeth Ann Harper. Riley, Carroll L. Rio del Norte: compiled by Shaun Briley of the Storms Brewed in Other Men's People of the Upper Rio Grande San Diego Public Library, Worlds: The Confrontation of from the Earliest Times to the provides a range of perspectives Indians, Spanish, and French in Pueblo Revolt. Salt Lake City: on the issues raised by the the Southwest, 1540-1795. University of Utah Press, 1995. upcoming P.O.V. documentary Norman, OK: University of A book about Pueblo Indian culture “The Last Conquistador” that Oklahoma Press, 1996. John and history. premieres on July 15th, 2008 at describes the Spanish, the French, 10 PM (check local listings at and American colonization spanning Roberts, David. The Pueblo www.pbs.org/pov/). from the Red River to the Colorado Revolt: The Secret Rebellion Plateau. That Drove the Spaniards Out of Renowned sculptor John Houser has the Southwest. New York: a dream: to build the world’s tallest Kammen, Michael. Visual Shock: Simon & Schuster, 2004. Roberts bronze equestrian statue for the city A History of Art Controversies in describes the Pueblo revolt of 1680, of El Paso, Texas. He envisions a American Culture. New York: which resulted in a decade of stunning monument to the Spanish Vintage, 2007. Pulitzer Prize independence before the Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate that winner Kammen examines how reasserted dominion over the area. will pay tribute to the contributions particular pieces of public art in Hispanic people made to building America’s history have sparked Schama, Simon. -

Residential Schools, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylania Press, 2004

Table of Contents I.Introduction 3 II. Historical Overview of Boarding Schools 2 A. What was their purpose? 2 B. In what countries were they located 3 United States 3 Central/South America and Caribbean 10 Australia 12 New Zealand 15 Scandinavia 18 Russian Federation 20 Asia 21 Africa 25 Middle East 24 C. What were the experiences of indigenous children? 28 D. What were the major successes and failures? 29 E. What are their legacies today and what can be learned from them? 30 III. The current situation/practices/ideologies of Boarding Schools 31 A. What purpose do they currently serve for indigenous students (eg for nomadic communities, isolated and remote communities) and/or the solution to address the low achievements rates among indigenous students? 31 North America 31 Australia 34 Asia 35 Latin America 39 Russian Federation 40 Scandinavia 41 East Africa 42 New Zealand 43 IV. Assessment of current situation/practices/ideologies of Boarding Schools 43 A. Highlight opportunities 43 B. Highlight areas for concern 45 C. Highlight good practices 46 V. Conclusion 48 VI. Annotated Bibliography 49 I. Introduction At its sixth session, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues recommended that an expert undertake a comparative study on the subject of boarding schools.1 This report provides a preliminary analysis of boarding school policies directed at indigenous peoples globally. Because of the diversity of indigenous peoples and the nation-states in which they are situated, it is impossible to address all the myriad boarding school policies both historically and contemporary. Boarding schools have had varying impacts for indigenous peoples. -

Out of This World.Pdf

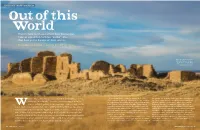

ANCIENT NEW MEXICO Out of this World There’s more to Chaco Culture than the Canyon. Take an expedition to three “outlier” sites that have yet to divulge all their secrets. BY CHARLES C. POLING | PHOTOS BY KIRK GITTINGS The main building complex at Pueblo Pintado, 16 miles from Chaco Canyon. Very little archaeological study has taken place here. ith so much of its human past scattered in plain sight across the Less well known but equally captivating, the so-called In exchange for expending a little extra effort in getting there, Chaco outlier sites deliver an off-grid foray into the world of the Chaco outliers reward you with the sense of unmediated landscape, New Mexico offers the casual day-tripper and more the 11th-century Ancestral Puebloans, without such amenities adventure and discovery that drives archaeologists into the serious archaeology buff an amazing range of sites to visit. As the as the Visitors Center and paths that make Chaco Canyon field in the first place. A sample trio of sites that begins a W accessible to 40,000 visitors a year. Researchers believe that couple hours from Albuquerque—Guadalupe, Pueblo Pintado, poster child for ancient ruins here and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Chaco Chaco Canyon was intimately related to 75 other settlements and Kin Ya’a—opens a window on the fascinating architectural Canyon stands with sites like the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, and the Great in a single cultural web flung across 30,000 square miles magnificence, the luminous high-desert environs, the social Wall of China for its uniqueness and its high levels of political, economic, and and reaching into Colorado and Utah, all tied together by a complexity, and the unresolved mysteries of the Ancestral cultural development. -

COMMUNITY-BASED FOREST MANAGEMENT and NATIONAL LAW in ASIA and the PACIFIC BALANCING ACTS: Community-Based Forest Management and National Law in Asia and the Pacific

u r COMMUNITY-BASED FOREST MANAGEMENT AND NATIONAL LAW IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC BALANCING ACTS: Community-Based Forest Management and National Law in Asia and the Pacific Owen J. Lynch Kirk Talbott -'-'— in collaboration with Marshall S. Berdan, editor Jonathan Lindsay and Chhatrapati Singh (India Case Study) Chip Barber (Indonesia Case Study) TJ Shantam Khadka (Nepal Case Study) WORLD Alan Marat (Papua New Guinea Case Study) RESOURCES Janis Alcorn (Thailand Case Study) INSTITUTE Antoinette Royo-Fay (Philippines Case Study) Lalanath de Silva and G.L. Anandalal SEPTEMBER 1995 Nanayakkara (Sri Lanka Case Study) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lynch, Owen J. (Owen James) Balancing acts : community-based forest management and national law in Asia and the Pacific / Owen J. Lynch and Kirk Talbott with Marshall S. Berdan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56973-033-4 (alk. paper) 1. Forestry law and legislation—Asia. 2. Forestry law and legislation—Pacific Area. I. Talbott, Kirk, 1955- II. Berdan, Marshall S. III. Title. KNC768.L96 1995 346.504'675—dc20 [345.064675] 95-34925 CIP Kathleen Courrier Publications Director Brooks Belford Marketing Manager Hyacinth Billings Production Manager Lomangino Studio Cover Design Chip Fay Cover Photos Each World Resources Institute Report represents a timely, scholarly treatment of a subject of public concern. WRI takes responsibility for choosing the study topics and guaranteeing its authors and researchers freedom of inquiry. It also solicits and responds to the guidance of advisory panels and expert reviewers. Unless otherwise stated, however, all the interpretation and findings set forth in WRI publications are those of the authors. -

THE STORY of MINING in New Mexico the Wealth Qjthe World Will B~ Jqund in New Mexico and Arizona

Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1-SANTA FE, NEw MEXICO No. 2-TAos-RED RIVER-EAGLE NEsT, NEw MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE No. 3-RoswELL-CAPITAN-Rumoso AND BoTTOMLEss LAKES STATE PARK, NEw MExiCo No. 4-SouTHERN ZuNI MouNTAINS, NEw MExico No. 5-SILVER CITY-SANTA RITA-HURLEY, NEw MEXICO No. 6-TRAIL GumE To THE UPPER PEcos, NEw MExiCo No. 7-HIGH PLAINS NoRTHEASTERN NEw MExico, RAToN- CAPULIN MouNTAIN-CLAYTON No. 8-MosAic oF NEw MExico's ScENERY, RocKs, AND HISTORY No. 9-ALBUQUERQUE-hs MouNTAINS, VALLEYS, WATER, AND VoLcANOEs No. 10-SouTHwEsTERN NEw MExico N 0. 11-CUMBRES AND T OLTEC. SCENIC RAILROAD No. 12-THE STORY oF MINING IN NEw MExiCo The wealth Qjthe world will b~ jQund in New Mexico and Arizona. -Baron vonHumboldt, 1803 Political Essay on New Spain S.cet1ic Trips lo the (1eologi<;Pas(. N9.12 New Mexico Buteau of Mines & MineNll Resources ADIVISIQN OF NEW ME)(lCO•INS'f!TtJTE OF MINING &TECHNOtOGY The Story of Mining in New Mexico 9Y p AIG.E W. CHRISTIANSEN .lllustcr:(t~d by Neila M., P~;arsorz . -· SocoRRo 1974 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. CoLGATE, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KorrLOWSKI, Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Supen'ntendent of Public lnstrnction Appointed William G. Abbott, President, 1961-1979, Hobbs George A. Cowan, 1972-1975, Los Alamos Dave Rice, 1972-1977, Carlsbad Steve Torres, !967-1979, Socorro James R. Woods, !971-1977, Socorro BUREAU STAFF Full Time WILLIAM E. -

Uimersity Mcrofihns International

Uimersity Mcrofihns International 1.0 |:B litt 131 2.2 l.l A 1.25 1.4 1.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS STANDARD REFERENCE MATERIAL 1010a (ANSI and ISO TEST CHART No. 2) University Microfilms Inc. 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages In any manuscript may have Indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When It Is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to Indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to Indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right In equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page Is also filmed as one exposure and Is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or In black and white paper format. * 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarify on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available In black and white standard 35mm slide format.* *For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. -

Understanding the Creolization

“TRAGEDY AND GLORY” IN THE “UNFORTUNATE ERA”: UNDERSTANDING THE CREOLIZATION OF SANTO DOMINGO THROUGH THE BOCA NIGUA REVOLT by Jonathan Hopkins B.A., The University of Victoria, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERISTY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) September 2017 © Jonathan Hopkins, 2017 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the College of Graduate Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: “TRAGEDY AND GLORY” IN THE “UNFORTUNATE ERA”: UNDERSTANDING THE CREOLIZATION OF SANTO DOMINGO THROUGH THE BOCA NIGUA REVOLT submitted by in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Jonathan Hopkins the degree of . Master of Arts Dr. Luis LM Aguiar Supervisor Dr. Jessica Stites-Mor Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Jelena Jovicic Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Catherine Higgs University Examiner Dr. Donna Senese External Examiner iii Abstract This thesis examines a slave revolt that occurred at the Boca Nigua sugar plantation in Santo Domingo (today the Dominican Republic) during the fall of 1796. The Spanish colony’s population at the time were coming to terms with revolution in St. Domingue (the French territory it shared an island with) and Santo Domingo’s cession to France in 1795. I argue the slave rebels who initiated the revolt at Boca Nigua and the colonial officials responsible for subduing it were influenced by creolization. Conceptually, the process involves people from divergent geographic origins arriving to the Caribbean through mass migration, and forging local cultures through the economic and political arrangements found in the colonial world. -

Mexicans in New Mexico: Deconstructing the Tri-Cultural Trope

Mexicans in New Mexico: Deconstructing the Tri-Cultural Trope Item Type Article Authors Fairbrother, Anne Citation Fairbrother, Anne. "Mexicans in New Mexico: Deconstructing the Tri-Cultural Trope." Perspectives in Mexican American Studies 7 (2000): 111-130. Publisher Mexican American Studies & Research Center, The University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Perspectives in Mexican American Studies Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents Download date 30/09/2021 22:07:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624842 MEXICANS IN NEW MEXICO: DECONSTRUCTING THE TRI -CULTURAL TROPE Anne Fairbrother If Coronado and Ouate were to meet, would they recognize their own people? What vestiges of the colonies created by Conquistadores would they find? What would they say of that riotous preoccupation about Spanish origins, recalling, with a smile, that none of the great leaders brought a wife or family with him? Arthur L. Campa' Arthur Campa, the renowned folklorist who wrote in the 1930s and 1940s, provides a refreshing response to the "preoccupation about Spanish origins" in New Mexico, and should be a key voice in the discourse around the tri -cul- tural trope2 that represents New Mexico today. That tri -cultural image is of the Indian, the Hispano, and the Anglo, and that image manifests itself in public enactments, in tourism publicity, and has penetrated the collective consciousness of the region. The questions that must be asked in this region so recently severed from Mexico, and so long the outpost of an empire of colonized mestizos, are: Why is the mestizo, the mexicano, excluded from that iconic image? Why was the mes- tizo invisible and unheard from the time of the U.S.