Linear Film 114 - Online Space 118

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12

Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12 Company number 5042279 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12 1 Contents Paul Hamlyn Foundation 2 Chair’s statement 4 Director’s report 6 Arts programme 8 Education and Learning programme 13 Social Justice programme 20 India programme 25 Other grants 26 Evaluation report 28 Reference and administrative details and audit report 31 List of grants awarded in 2011/12 36 Financial review 53 Statement of Financial Activities, Balance Sheet and Cashflow Statement 57 Notes to the financial statements 60 Trustees, staff and advisors 70 2 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Paul Hamlyn was an entrepreneur, publisher and philanthropist, committed to providing new opportunities and experiences for people regardless of their background. From the outset, his overriding concern was to open up the arts and education to everyone, but particularly to young people. In 1987, he established the Paul Hamlyn Foundation for general charitable purposes. Since then, we have continuously supported charitable activity in the areas of the arts, education and learning and social justice in the UK, enabling individuals, especially children and young people, to experience a better quality of life. We also support local charities in India that help the poorest communities in that country gain access to basic services. Paul Hamlyn died in August 2001, but the magnificent bequest of most of his estate to the Foundation enabled us to build on our past approaches. Mission To maximise opportunities for individuals and communities to realise their potential and to experience and enjoy a better quality of life, now and in the future. -

Accepted Film List

Run Screening Screening Screening Title Year Premiere? Director Time Icons Synopisis: 3-line Venue Date Time The Amateurs 2005 Michael Traegers 97 Mins. Michael Traeger's directorial debut The Amateurs is a hillarious, sexy comedy about this small Cable Car August 10th 5:00 PM town's attempt to make what becomes the world's most innocent adult film. The quest begins innocently enough with Andy (Jeff Bridges) seeing that sex is everywhere; in the paper, all over town, everywhere. It's a multi-billion dollar industry, and better yet, one of its more popular forms is the amateur variety. And Andy and his friends are indeed amateurs, so better yet, one of its more popular forms is the amateur variety. And Andy and his friends are indeed amateurs, so why shouldn't they be able to strike it rich in this booming industry? The Amateurs is a sweetly comic film that plays with the conventions of filmmaking and the movie business all while having fun with its good-hearted characters. Land of the Blind 2006 Robert Edwards 101 Min. LAND OF THE BLIND is a satiric and timely political drama about terrorism, revolution, and the Cable Car August 10th 7:00 PM power of memory. In an unnamed place and time, an idealistic soldier named Joe (Ralph Fiennes) strikes up an illicit friendship with a political prisoner named Thorne (Donald Sutherland), who eventually recruits him into a bloody coup d'etat. But in the post-revolutionary world, what Thorne asks of Joe leads the two men into bitter conflict, spiraling downward into madness until Joe's co- conspirators conclude that they must erase him from history. -

BH3 Gobsheet

25th February 2021 Website – http://www.berkshirehash.co.uk Email – [email protected] THE HASHLESS TIMES LIGHT AT THE END OF THE DARKEST TUNNEL ithout wishing to tempt Fate into giving us all another damn good kicking I have to say that it looks very likely that we will be Hashing again soon. The Government has defined 4 steps that W should take us out of lockdown – see here for full details. Included in Step 1 (assuming there are no setbacks) is the allowing of 6 people to meet outdoors and ‘people will be able to take part in formally organised outdoor sports’. Cue (virtual) Mexican Wave! The BH3 Committee is meeting (again virtually) next week to discuss safe and legal options so keep any eye out for communications. It will be so nice to Hash again. MEMBERS’ NEWS So what have you all been doing recently? From the Whatsapp video conversations Donut and I have been having with various Hashers it consists of working, walking, running, soup-making, bread baking, wine drinking and house decorating. I’m sure you will all be pleased to know that, along with his very supportive (and long-suffering ) wife, TC, Whinge’s health has been improving and they have been out walking ridiculous distances. Last week, they rang our doorbell (and interrupted a rather pleasant lunchtime cheese toastie) for a chat during one of their walks. Great to see them, even though outside and at a distance. We found out later that they had walked a total of 12.3 miles! Apparently, Whinge was somewhat stiff of muscle the day after. -

Download Publication

CONTENTS History The Council is appointed by the Muster for Staff The Arts Council of Great Britain wa s the Arts and its Chairman and 19 othe r Chairman's Introduction formed in August 1946 to continue i n unpaid members serve as individuals, not Secretary-General's Prefac e peacetime the work begun with Government representatives of particular interests o r Highlights of the Year support by the Council for the organisations. The Vice-Chairman is Activity Review s Encouragement of Music and the Arts. The appointed by the Council from among its Arts Council operates under a Royal members and with the Minister's approval . Departmental Report s Charter, granted in 1967 in which its objects The Chairman serves for a period of five Scotland are stated as years and members are appointed initially Wales for four years. South Bank (a) to develop and improve the knowledge , Organisational Review understanding and practice of the arts , Sir William Rees-Mogg Chairman Council (b) to increase the accessibility of the art s Sir Kenneth Cork GBE Vice-Chairma n Advisory Structure to the public throughout Great Britain . Michael Clarke Annual Account s John Cornwell to advise and co-operate wit h Funds, Exhibitions, Schemes and Awards (c) Ronald Grierson departments of Government, local Jeremy Hardie CB E authorities and other bodies . Pamela, Lady Harlec h Gavin Jantje s The Arts Council, as a publicly accountable Philip Jones CB E body, publishes an Annual Report to provide Gavin Laird Parliament and the general public with an James Logan overview of the year's work and to record al l Clare Mullholland grants and guarantees offered in support of Colin Near s the arts. -

SPANISH FORK PAGES 1-20.Indd

November 14 - 20, 2008 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, November 14 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey b News (N) b CBS Evening News (N) b Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Threshold” The Price Is Right Salutes the NUMB3RS “Charlie Don’t Surf” News (N) b (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight (N) b Troops (N) b (N) b Letterman (N) KJZZ 3 High School Football The Insider Frasier Friends Friends Fortune Jeopardy! Dr. Phil b News (N) Sports News Scrubs Scrubs Entertain The Insider The Ellen DeGeneres Show Ac- News (N) World News- News (N) Access Holly- Supernanny “Howat Family” (N) Super-Manny (N) b 20/20 b News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4 tor Nathan Lane. (N) Gibson wood (N) b line (N) wood (N) (N) b News (N) b News (N) b News (N) b NBC Nightly News (N) b News (N) b Deal or No Deal A teacher returns Crusoe “Hour 6 -- Long Pig” (N) Lipstick Jungle (N) b News (N) b (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night KSL 5 News (N) to finish her game. b Jay Leno (N) b TBS 6 Raymond Friends Seinfeld Seinfeld ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (G, ’39) Judy Garland. (8:10) ‘Shrek’ (’01) Voices of Mike Myers. -

Record World Sales Iintder Motion for a Temporary Re- Straining Order Blocking the Single's Release

NEWSPAPER ISSN 0034-1622 Ztilea...," 1.1(12,Lic:c. SEPTEMBER 20, 1980 $2. Stephanie Mills A Saluteto to Teddy Pendergrass SINGLES ALBUMS DONNA SUMMER, "THE WANDERER" STEVIE WONDER, "MASTER BLASTER THE B -52's, "WILD PLANET." The (prod. by Moroder-Bellotte) (JAMMIN')" (prod. by Wonder) idiosyncratic Georgia quintet's de- (G M PC / Sweet Summer Night, (writer: Wonder) (Jobete/Black but LP was an AOR and club sleep- ASCAP) (3:44). One of Summer's Bull, ASCAP) (4:49). Blending er that wouldn't stop selling, and most eclectic outings. She draws topical urban street themes with their second album indicates that from numerous influences to cre- reggae -pop rhythms, Wonder the relentless, dance - crazed ate a seductive rocker. Vocal creates a compelling single from rhythms haven't stopped either. In- quivers & keyboard vamps do the his forthcoming "Hotter Than cludes "Private Idaho." Warner job. Geffen 49563 (WB). July" LP. Tamla 54317 (Motown). Bros. BSK 3471 (7.98). SUPERTRAMP, "DREAMER" (prod. by KANSAS, "HOLD ON" (prod. by group) GARY NUMAN, "TELEKON." Numan Henderson -Pope) (writers: Da- (writer: Livgren) (Don Kirshner/ may not have been the first prac- vies -Hodgson) (Almo/Delicate, Blackwood, BMI) (3:45). From titioner of techno-pop, but his sim- ASCAP) (3:15). This live cut from the new "Audio -Visions" LP plified approach and lilting lyric the forthcoming double -LP set comes this ballad with a recur- patterns seem to be the most ideally is a to get cinch immediate pop ring surge of power at the hook. suited to pop radio formats, as indi- reaction. -

Bradmore Lunches

ABBOTT William Abbot of Bradmore received lease from Sir John Willughby 30.6.1543. Robert Abbot married Alice Smyth of Bunny at Bunny 5.10.1566. Henry Sacheverell of Ratcliffe on Soar, Geoffrey Whalley of Idersay Derbyshire, William Hydes of Ruddington, Robert Abbotte of Bradmore, John Scotte the elder, son and heir of late Henry Scotte of Bradmore, and John Scotte the younger, son and heir of Richard Scotte of Bradmore agree 7.1.1567 to levy fine of lands, tenements and hereditaments in Bradmore, Ruddington and Cortlingstocke to William Kinder and Richard Lane, all lands, tenements and hereditaments in Bradmore to the sole use of Geoffrey Walley, and in Ruddington and 1 cottage and land in Bradmore to the use of Robert Abbotte for life and after his death to Richard Hodge. Alice Abbott married Oliver Martin of Normanton at Bunny 1.7.1570. James Abbot of Bradmore 20.10.1573, counterpart lease from Frauncis Willughby Ann Abbott married Robert Dawson of Bunny at Bunny 25.10.1588. Robert Abbot, of Bradmore? married Dorothy Walley of Bradmore at Bunny 5.10.1589. Margery Abbott married Jarvis Hall/Hardall of Ruddington at Bunny 28.11.1596. William Abbot of Bradmore, husbandman, married Jane Barker of Bradmore, widow, at Bunny 27.1.1600, licence issued 19.1.1600. 13.1.1613 John Barker of Newark on Trent, innholder, sold to Sir George Parkyns of Bunny knight and his heirs 1 messuage or tenement in Bradmere now or late in the occupation of William Abbott and Jane his wife; John Barker and his wife Johane covenant to acknowledge a fine of the premises within 7 years. -

06 12-9 TV Guide.Indd 1 12/9/08 8:00:03 AM

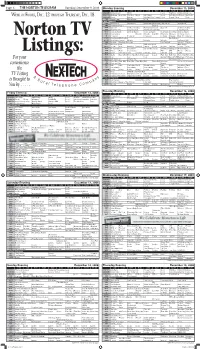

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, December 9, 2008 Monday Evening December 15, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Charlie Brown 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , DEC . 12 THROUGH THURSDAY , DEC . 18 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Worst CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Chuck Heroes My Own Worst Enemy Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Manhunter Manhunter The First 48 Intervention AMC A Christmas Carol Prancer ANIM Cats 101 It's Me or the Dog Animal Cops Detroit Cats 101 It's Me or the Dog CNN Brown-No Bias Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Jesus-Complete Jesus-Complete Jesus-Complete How-Made How-Made Jesus-Complete DISN Stuart Little 2 Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! E! Special E! Special E! Special E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Special Norton TV ESPN Countdown NFL Football SportsCenter ESPN2 Bowl Mania Special Billiards Billiards Billiards Fastbreak NFL FAM Rudolph Charlie & Chocolate The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX Christmas-Krank Christmas-Krank Black Knight HGTV To Sell Curb Amazing Potential House House Buy Me Beyond To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Christmas Unwrapped Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Secret Santa Will Will Frasier Frasier Listings: MTV Made The Hills Spoof'd The Hills The Hills Hills The Hills Hills Exiled NICK iCarly SpongeBob Home Imp. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Mothers on Mothers: Maternal Readings of Popular Television

From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. The volume examines the ways in which these women find pleasure, empowerment, escapist fantasy, displeasure and frustration in popular depictions of motherhood. The research seeks to present the MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION voice of the maternal audience and, as such, it takes as its starting REBECCA FEASEY point those maternal depictions and motherwork representations that are highlighted by this demographic, including figures such as Tess Daly and Katie Hopkins and programmes like TeenMom and Kirstie Allsopp’s oeuvre. Rebecca Feasey is Senior Lecturer in Film and Media Communications at Bath Spa University. She has published a range of work on the representation of gender in popular media culture, including book-length studies on masculinity and popular television and motherhood on the small screen. REBECCA FEASEY ISBN 978-0343-1826-6 www.peterlang.com PETER LANG From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. -

Rainbowtimesnews.Com FREE!

Year 2, Vol. 25 • Aug. 7 - Sept. 3, 2008 The www.therainbowtimesnews.com FREE! The L Word news that avid CT same-sex marriage: RainbowTimes fans were hoping for here! Sign pledge, it matters Your LGBT News in Western MA, the Capital District of NY, Northern CT, & Southern VT p. 13 p. 17 JJEESSSSEE AARRCCHHEERR OPPPPEEDDIISSAANNOOSS’ SSTTAARRSS IIN NNEEWW O ’ UUNNCCEENNSSOORREEDD BBOOOOKK FFIILLMM P.. 6 P.. 12 NNYY CCOOUUPPLLEESS RRUUSSHH TO MMAA TO TTIIEE--TTHHEE--KKNNOOTT P.. 3 TTRRAANNSS--DDAATTIINNGG:: IIT’’S DDIIFFFFEERREENNTT!! P.. 4 RRUUEE MMCCCCLLAANNAAHHAANN:: TTHE GGOOLLDDEENN GGIIRRLLSS’’ NNEEWW PPRROOJJEECCTT P.. 8 LLGGBBTT--FFRRIIEENNDDLLYY RREETTIIRREEMMEENNTT CCOOMMMMUUNNIITTYY WWAANNTTSS YYOOUU!! P.. 5 Photo by: Walter Kurtz 2 • Aug. 7 - Sept. 3, 2008 • The Rainbow Times • www.therainbowtimesnews.com Opinions Economics & same-sex marriage The Controversial Couch By: Nicole C. Lashomb*/ TRT Editor-in-Chief breaks, hospitalization/visitation rights, Lie back and listen. Then get up and do something On July 29, 2008, the Mass. House voted pension survivor benefits, amongst others. By: Suzan Ambrose*/TRT Columnist their precious puss-in-boots and to repeal a 1913 state law that prohibited The business of same sex-marriage is pooches. Why, just pick up an almost all out-of-state gay and lesbian cou- also proving beneficial for local Fluffy. Puffy. Muffy. Furrface. issue of any queer rag and you’ll ples from legally marrying in economies. You’ve guessed it. These are all eventually come across a sec- Massachusetts. This repeal was favored in In a report by The New York Times, names lovingly used to describe my warm, tion entitled “Lesbians and Their Pets.” little pussy ..