Ottawa 2014 Air Quality and Climate Change Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDITOR's CORNER Page 2 WHAT EVENT IS USEFUL

ESLA: LEARNING FUN December, 2013 Volume 1, Number 1 FEATURE WHAT EVENT IS USEFUL? PAGE 2 “Taste of Russia” Festival Farm Proulx, Orleans September 29, 2013,Ottawa 19th Annual Pumpkin Halloween Festival Photo by E. Kaliberda October, 2013 Photo by E. Kaliberda WHAT’S COMING UP! EDITOR’S CORNER Questions? Comments? page 2 Suggestions? Ideas? WHAT EVENT IS USEFUL ? page 2 [email protected] 10 IDEAS FOR EVENTS We would love to hear from you! page 3-6 BOOK PRESENTATION page 7-8 CALENDAR FOR DECEMBER page 9 2 EDITOR’S CORNER Welcome to the special edition of the ESLA: Learning fun newsletter! Let me introduce myself. My name is Elena Kaliberda and I am an Editor of this special edition of the ESLA newsletter. I am also the ESLA 1900 course student at the Carleton University. Students like me are the prime readers of this newsletter. One of the key objectives of the ESLA program is to improve the academic knowledge of the English language and get some practical communication skills. Surely, there are many opportunities available at the Carleton University to get involved and practise your communication skills, for example “English as a second language” conversation groups, workshops, seminars, and many others. There are always many various events happening at Carleton, including international conferences, seminars, theatre performances and much more. But it is also important to take advantage of many other opportunities that are available outside the University walls. It is important for so many different reasons. The key here is to receive a real life experience and an opportunity to integrate into every day’s life and learn to communicate in English with ease. -

Festival Capital

WELCOME TO CANADA’S FESTIVAL CAPITAL FOR WHAT’S ON RIGHT NOW For an authentic local OTTAWAFESTIVALS.CA experience, check out the Pour100+ uneannual expérienc festiveals, locale authentiquespecial events, consult andez lesfairs plus that de 100mak festive Ottaals,wa événementsextraordinary!* spéciaux et foires qui font d'Ottawa There’s something here une ville extraordinaire!* for everyone— Chacun y trouvera son from neighbourhood bonheur – allant de celebrations to fêtes de quartier à des festivinternationallyals de renommée intrenoernationalewned festiv et alstoute sortande ev deerything choses entre lesin betw deuxeen— – dur ant talloutyeear l'année long.. * Ottawa a été reconnue deux fois * Ottawa has been recognized twice as comme étant la ville mondiale a World Festival and Event City des festivals et des événements by the International Festivals par l'Association internationale and Events Association. des festivals et événements. BIENVENUE À LA CAPITALE DES FESTIVALS POUR SAVOIR TOUT CE QUI SE PASSE EN CE MOMENT DU CANADA! OTTAWAFESTIVALS.CA Pour une expérience locale authentique, consultez les plus de 100 festivals, événements spéciaux et foires qui font d'Ottawa une ville extraordinaire!* Chacun y trouvera son bonheur – allant de fêtes de quartier à des festivals de renommée internationale et toute sorte de choses entre les deux – durant toute l'année. * Ottawa a été reconnue deux fois comme étant la ville mondiale des festivals et des événements par l'Association internationale des festivals et événements. OTTAWAFESTIVALS.CA -

2019 City Wide Development Charges Background Study

2019 City-Wide Development Charges Background Study Version for Public Consultation HEMSON C o n s u l t i n g L t d. March 15, 2019 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .......................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 2 A. Purpose of 2019 Development Charges (DC) Background Study .. 2 B. City-Wide and Area-Specific DCs Have Been Calculated ............... 3 C. Development Forecast .................................................................... 4 D. Public Transit Ridership Forecast ................................................... 5 E. Calculated Development Charges .................................................. 5 F. Cost of Growth Analysis .................................................................. 6 G. Development Charges Administration & Policy Considerations ...... 7 I Purpose of 2019 Development Charges Background Study ............. 8 A. Introduction and Background .......................................................... 8 B. Legislative Context .......................................................................... 9 C. The 2019 DC Study is Intended to be an Interim Update ................ 9 D. Consultation And Approval Process ................................................ 9 E. Key Steps In Determining DCs for Future Development-Related Projects ......................................................................................... 10 F. Long-Term Capital -

Ottawa Transportation Report.Pdf

OTTAWA THE IMPACT OF TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENTS ON HOUSING VALUES IN THE OTTAWA REGION Don R Campbell, Senior Analyst Melanie Reuter, Director of Research Allyssa Epp, Research Analyst WWW.REINCANADA.COM AUTHORS Don R. Campbell, Senior Analyst, REIN Ltd Melanie Reuter, Director of Research, REIN Ltd Allyssa Fischer, Research Analyst, REIN Ltd © The Real Estate Investment Network Ltd. 6 – 27250 58 Cr Langley, BC V4W 3W7 Tel (604) 856-2825 Fax (604) 856-0091 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Page: www.reincanada.com Important Disclaimer: This Report, or any seminars or updates given in relation thereto, is sold, or otherwise provided, on the understanding that the authors – Don R. Campbell, Melanie Reuter, Allyssa Fischer, and The Real Estate Investment Network Ltd and their instructors, are not responsible for any results or results of any actions taken in reliance upon any information contained in this report, or conveyed by way of the said seminars, nor for any errors contained therein or presented thereat or omissions in relation thereto. It is further understood that the said authors and instructors do not purport to render legal, accounting, tax, investment, financial planning or other professional advice. The said authors and instructors hereby disclaim all and any liability to any person, whether a purchaser of this Report, a student of the said seminars, or otherwise, arising in respect of this Report, or the said seminars, and of the consequences of anything done or purported to be done by any such person in reliance, whether in whole or part, upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Report or the said seminars. -

300 Tremblay Road TIA Strategy Report

300 Tremblay Road TIA Strategy Report Prepared for: TCU Development Corporation 150 Isabella Street, Suite 100 Ottawa, ON K1S 5H3 Prepared by: Parsons 1223 Michael Street North, Suite 100 Ottawa, ON K1J 7T2 477570 - 01000 1335 & 1339 Bank Street –Scoping Report 1 Document Control Page CLIENT: TCU Development Corporation PROJECT NAME: 300 Tremblay Road REPORT TITLE: TIA Step 4 Strategy Report PARSONS PROJECT NO: 477570-01000 VERSION: Draft DIGITAL MASTER: \\XCCAN57FS01\Data\ISO\477570\1000\DOCS\STEP3-Forecasting\300 Tremblay - TIA Step 3 Forecasting Report.docx ORIGINATOR Juan Lavin, E.I.T. REVIEWER: Matt Mantle, P.Eng. AUTHORIZATION: CIRCULATION LIST: Mike Giampa, P.Eng. 1. TIA Step 1 Screening Form – July 9, 2020 2. TIA Step 2 Scoping Report – July 27, 2020 HISTORY: 3. TIA Step 3 Forecasting Report – August 21, 2020 4. TIA Step 4 Strategy Report – September 18, 2020 300 Tremblay Road – Strategy Report i TABLE OF CONTENTS DOCUMENT CONTROL PAGE ...................................................................................................................................... I 1. SCREENING FORM .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. SCOPING REPORT ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1. EXISTING AND PLANNED CONDITIONS .................................................................................................. 1 -

Recommended Plan.Pdf

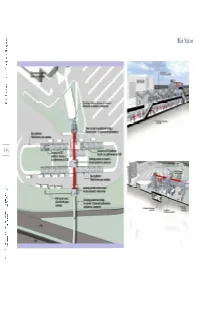

Blair Station 9-34 Maintenance and Storage Facility Track redundancy within the facility will be provided to ensure The proposed Maintenance and Storage Facility is an integral the ability to move LRVs under vehicle or system failure part of the project, as it will: conditions. • House and service all of the trains needed to operate the The preferred site for the Maintenance and Storage Facility has line been determined based on the following criteria: • Service vehicles to be used on future LRT lines • Site Characteristics (topography, grade, land use compatibility, expansion capability and environmental • House the operations control centre (signalling, considerations) communications) for the line • Facility Operations (turnaround loops, track redundancy, • Be the primary heavy maintenance facility for the LRT layout efficiency and municipal services) network Maintenance of the LRVs is crucial to maintain vehicle • System Operations (connectivity to the line, efficiency and manufacturer's warranties, minimize long term operating costs access to freight rail), and and provide for system safety and reliability. The Maintenance • Relative Costs (capital, operating, maintenance and and Storage Facility will accommodate the following elements property ownership and acquisition) on-site: The proposed Maintenance and Storage Facility for the DOTT 9-35 • Main facility building housing offices, roster areas, meeting project will be located on lands to the west of the existing OC rooms and control equipment Transpo headquarters and bus maintenance facility located on • Storage yard for regular cleaning and minor maintenance the north side of Belfast Road, west of St. Laurent Boulevard and south of the VIA rail corridor. In order to access this • Repair areas for heavy and light maintenance areas for location, a connecting track is required between the DOTT vehicles alignment and the Maintenance and Storage Facility. -

Capital Budget 13 Project Details 14 Transit Services 14 4 Year Forecast 34 Works-In-Progress Listing 36

Transit Commission Tabled November 4, 2020 Table of Contents Transit Commission Service Area Summary 1 Operating Resource Requirement 3 User Fees 4 Capital Funding Summary 7 Operating & Capital Supplemental Information 8 Analysis 8 Explanatory Notes 10 Capital Budget 13 Project Details 14 Transit Services 14 4 Year Forecast 34 Works-In-Progress Listing 36 Transportation Services Department 2021 Service Area Summary - OC Transpo The Transportation Services Department brings together all services related to the mobility of the city, integrating the planning, implementation, operations and delivery of all modes of transportation. Every service and project delivered by the department impacts how people commute – whether by train, bus, car, bicycle, walking or a combination of these – both now and in years to come. The department operates the OC Transpo system to provide travel options that meet the needs and expectations of customers. All trains and buses are 100 per cent accessible. Both Ottawa and OC Transpo underwent a major transformation with the opening of O-Train Line 1, the Confederation Line last year. The transformation to a multimodal transit system marked a significant change to the way OC Transpo provides service to customers, and the way customers use public transit. OC Transpo works to provide a safe, reliable, comfortable, courteous and affordable transit service for all, to build and retain an engaged workforce, and to meet the policy objectives set by Council and the Transit Commission, all within the established budget. -

Carp Hills/South March Highlands Bio-Blitz 2011 (PDF)

Carp Hills –South March Highlands Bio‐blitz 2011 Organized by Linda McCormick [email protected] Financial assistance for this project was provided by the Ottawa Stewardship Council Acknowledgements Prior to this experience, I had not participated in a bio‐blitz; nor do I have a background in biology. Therefore, I am intensely grateful to the support and assistance I received from the individuals and groups listed below. They made the event possible. The Ottawa Stewardship Council provided financial support and its members reviewed this report. The Council is part of the Ontario Stewardship Program, an initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. It is mandated to assist environmental groups, community associations, and other groups in Ottawa developing projects that promote and maintain a healthy environment (http://www.ottawastewardship.org/). Heather Hamilton from the Canadian Bio‐diversity Institute generously shared her time and expertise. She imported the concept of the bio‐blitz to North America a number of years ago and her enthusiasm for this method of promoting the natural environment is infectious. Nick Stow from the City of Ottawa provided support and assistance. He coordinated the design and production of maps of City‐owned property for bio‐blitz. Members of the Protect the South March Highlands Coalition promoted the bio‐blitz, set up the Nature Fair, provided operational support during the bio‐blitz and coordinated a dinner for participants. The Ottawa, Mississippi Valley and McNamara Field Naturalist Clubs promoted the event on their websites and in emails to their members. Members volunteered their time to participate in the Nature Fair and share their expertise. -

2019-December-January

December 2019 - January 2020 IMAGE decembre 2019 - janvier 2020 1 S A N D Y CCÔTE-DE-ÔTE-DE- H I L L SSABLEABLE DECEMBER 2019 - JANUARY 2020 DÉCEMBRE 2019 - JANVIER 2020 I MPhoto David Elden A G E Winds of change Crumbs whistle through Laurier Avenue from the shops City re Larry Newman rental ucas Nault is moving but he housing doesn’t know where. His hair salon has been in Sandy Hill at 232L Laurier East for 15 years, but will be Susan Young gone in 13 months. That wasn’t his plan. Lucas was a Sandy Hill resident in the t appeared promising, but in the end Versailles, on Henderson, when it was still Sandy Hill has little to celebrate. a family business. He just redecorated his Last fall, having engaged with shop and wasn’t planning on moving . stakeholdersI including Action Sandy Hill, ever. That was before the representative and having conducted an extensive study of Arnon Corp called and told him that of rental accommodation issues across they were not renewing his lease. town, Maclaren Municipal Consulting, Quel choc! Lucas said there was no room hired by the City, released an encouraging for negotiation: Arnon had another lessee. set of recommendations. I called Arnon at the number on the sign They endorsed taking a big step in on the second floor of the building next to the direction of a landlord licensing Lucas, and spoke to Michael Casey who is pilot program, something ASH in charge of leasing. He said that the new believes could be a comprehensive and tenant will likely be another franchise, proactive approach to improve quality probably controlled by MTY Food Group. -

Ottawa Welcomes the Confeder

OTTAWA WELCOMES THE CONFEDERATION LINE After delays and increasing political frustration, Ottawa’s first electrified light rail line is finally open – marking a new chapter for this Canadian transit pioneer. Vic Simons reports. aturday 14 September 2019 saw Mulroney said: “Ottawa residents deserve a passenger operations would be unachievable, the introduction of Ottawa’s latest world-class transportation system that gets by late 2016 enough track and overhead light rail service to the public – it both them and the economy moving… had been completed to allow LRV testing. was a day that many in the city had Today, that’s exactly what they are getting.” Coupled to infrastructure delays, the coming waited a long time for. winter months saw a number of problems SAlthough the city’s bus-served Transitways Approvals and delays identified with the chosen Alstom rolling have performed a valuable service for over 30 Approved by the city in late 2012, the current stock – a new ‘European-style’ low-floor years, planning for a more robust solution for CAD2.1bn (EUR1.5bn) east-west scheme was platform for the North American market, cross-city travel dates back to the early years originally scheduled to open to coincide with albeit based on a proven design – in the of the 21st Century. Indeed, a north-south the 150th anniversary of Canada becoming an form of heating and communications light rail route was designed, and contracts independent nation in 2017. This is reflected systems failures and carbody and brake awarded, in 2006. This project would have in the choice of the Confederation Line system issues. -

The Plan for Canada's Capital

Judicial i This page is intentionally left blank for printing purposes. ii The Plan for Canada’s Capital 2017 to 2067 NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION June 2016 iii The Capital of an extensive country, rapidly growing in population and wealth, possessed of almost unlimited water power for manufacturing purposes, and with a location admirably adapted not only for the building of a great city, but a city of unusual beauty and attractiveness. (…) Not only is Ottawa sure to become the centre of a large and populous district, but the fact that it is the Capital of an immense country whose future greatness is only beginning to unfold, (…) and that it be a city which will reflect the character of the nation, and the dignity, stability, and good taste of its citizens. Frederick Todd, 1903 “Preliminary Report to the Ottawa Improvement Commission” pp.1-2 iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For more than a century, the National Capital Commission (NCC) and its predecessors have embraced urban planning to promote the development, conservation and improvement of the National Capital Region, with the aim of ensuring that the nature and character of the seat of the Government of Canada is in accordance with its national significance. The consequences of these planning efforts have been the creation of parks and open spaces, public shorelines, campuses and clusters of government institutions, monuments and symbolic boulevards. This plan charts the future of federal lands in the National Capital Region between Canada’s sesquicentennial in 2017 and its bicentennial in 2067. It will shape the use of federal lands, buildings, parks, infrastructure and symbolic spaces to fulfill the vision of Canada’s Capital as a symbol of our country’s history, diversity and democratic values, in a dynamic and sustainable manner. -

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT & TREE CONSERVATION REPORT LOTS 18 & 19, CONCESSION I FORMER CITY of KANATA, CITY of OTTA

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT & TREE CONSERVATION REPORT LOTS 18 & 19, CONCESSION I FORMER CITY of KANATA, CITY of OTTAWA A report prepared for: 1384341 Ontario Ltd. by MUNCASTER ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING INC. Revised March, 2013 MUNCASTER ENVIRONMETAL PLANNING INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................1 1.1 Scoping the Environmental Impact Statement .........................................................3 2.0 METHODOLOGY ...............................................................................................................3 3.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS ..................................................................................................4 3.1 Geologic and Hydrologic Conditions.......................................................................4 3.2 Terrestrial Features ..................................................................................................6 3.3 Significant Features................................................................................................11 4.0 DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL ........................................................................................ 14 4.1 Proposed Land Use ................................................................................................14 4.2 Stormwater Management .......................................................................................16 5.0 POTENTIAL IMPACTS and MITIGATION MEASURES ..............................................16