The Historical Development of Section 1110 of the Bankruptcy Code Gregory P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Contents [Edit] Africa](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9562/contents-edit-africa-79562.webp)

Contents [Edit] Africa

Low cost carriers The following is a list of low cost carriers organized by home country. A low-cost carrier or low-cost airline (also known as a no-frills, discount or budget carrier or airline) is an airline that offers generally low fares in exchange for eliminating many traditional passenger services. See the low cost carrier article for more information. Regional airlines, which may compete with low-cost airlines on some routes are listed at the article 'List of regional airlines.' Contents [hide] y 1 Africa y 2 Americas y 3 Asia y 4 Europe y 5 Middle East y 6 Oceania y 7 Defunct low-cost carriers y 8 See also y 9 References [edit] Africa Egypt South Africa y Air Arabia Egypt y Kulula.com y 1Time Kenya y Mango y Velvet Sky y Fly540 Tunisia Nigeria y Karthago Airlines y Aero Contractors Morocco y Jet4you y Air Arabia Maroc [edit] Americas Mexico y Aviacsa y Interjet y VivaAerobus y Volaris Barbados Peru y REDjet (planned) y Peruvian Airlines Brazil United States y Azul Brazilian Airlines y AirTran Airways Domestic y Gol Airlines Routes, Caribbean Routes and y WebJet Linhas Aéreas Mexico Routes (in process of being acquired by Southwest) Canada y Allegiant Air Domestic Routes and International Charter y CanJet (chartered flights y Frontier Airlines Domestic, only) Mexico, and Central America y WestJet Domestic, United Routes [1] States and Caribbean y JetBlue Airways Domestic, Routes Caribbean, and South America Routes Colombia y Southwest Airlines Domestic Routes y Aires y Spirit Airlines Domestic, y EasyFly Caribbean, Central and -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Bankruptcy Tilts Playing Field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected]

Equity Research Airlines / Rated: Market Underweight September 15, 2005 Research Analyst(s): David Strine 212 272-7869 [email protected] Bankruptcy tilts playing field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected] Key Points *** TWIN BANKRUPTCY FILINGS TILT PLAYING FIELD. NWAC and DAL filed for Chapter 11 protection yesterday, becoming the 20 and 21st airlines to do so since 2000. Now with 47% of industry capacity in bankruptcy, the playing field looks set to become even more lopsided pressuring non-bankrupt legacies to lower costs further and low cost carriers to reassess their shrinking CASM advantage. *** CAPACITY PULLBACK. Over the past 20 years, bankrupt carriers decreased capacity by 5-10% on avg in the year following their filing. If we assume DAL and NWAC shrink by 7.5% (the midpoint) in '06, our domestic industry ASM forecast goes from +2% y/y to flat, which could potentially be favorable for airline pricing (yields). *** NWAC AND DAL INTIMATE CAPACITY RESTRAINT. After their filing yesterday, NWAC's CEO indicated 4Q:05 capacity could decline 5-6% y/y, while Delta announced plans to accelerate its fleet simplification plan, removing four aircraft types by the end of 2006. *** BIGGEST BENEFICIARIES LIKELY TO BE LOW COST CARRIERS. NWAC and DAL account for roughly 26% of domestic capacity, which, if trimmed by 7.5% equates to a 2% pt reduction in industry capacity. We believe LCC-heavy routes are likely to see a disproportionate benefit from potential reductions at DAL and NWAC, with AAI, AWA, and JBLU in particular having an easier path for growth. -

Comment: Maryland State Drone Law Puts Residents at Risk of Privacy Intrusions from Drone Surveillance by Law Enforcement Agencies Wayne Hicks

University of Baltimore Law Forum Volume 47 | Number 2 Article 5 2017 Comment: Maryland State Drone Law Puts Residents at Risk of Privacy Intrusions from Drone Surveillance by Law Enforcement Agencies Wayne Hicks Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/lf Part of the Administrative Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Hicks, Wayne (2017) "Comment: Maryland State Drone Law Puts Residents at Risk of Privacy Intrusions from Drone Surveillance by Law Enforcement Agencies," University of Baltimore Law Forum: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/lf/vol47/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Forum by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT MARYLAND STATE DRONE LAW PUTS RESIDENTS AT RISK OF PRIVACY INTRUSIONS FROM DRONE SURVEILLANCE BY LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES By: Wayne Hicks As technology rapidly advances, society is becoming more efficient and 2 interconnected than ever before. Unmanned Aircraft Systems ("UAS"), more frequently referred to as "drones," 3 have taken on an increasingly involved role in the progression towards a more interconnected society.4 For example, drones are presently capable of improving our ability to monitor potentially devastating storms, improving wildlife conservation efforts, increasing efficiency in agriculture, transporting goods to underdeveloped 1J.D. Candidate, 2017, University of Baltimore School of Law. I would like to thank the staff of the University of Baltimore Law Forum for all of their hard work throughout the drafting process. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

االسم Public Warehouse Co. األرز للوكاالت البحرية Volga-Dnepr

اﻻسم Public Warehouse Co. اﻷرز للوكاﻻت البحرية Volga-Dnepr Airlines NEPTUNE Atlantic Airlines NAS AIRLINES RJ EMBASSY FREIGHT JORDAN Phetchabun Airport TAP-AIR PORTUGAL TRANSWEDE AIRWAYS Transbrasil Linhas Aereas TUNIS AIR HAITI TRANS AIR TRANS WORLD AIRLINES,INC ESTONIAN AVIATION SOTIATE NOUVELLE AIR GUADELOUP AMERICAN.TRANS.AIR UNITED AIR LINES MYANMAR AIRWAYS 1NTERNAYIONAL LADECO LINEA AEREA DE1 COBRE. TUNINTER KLM UK LIMITED SRI LANKAN AIRLINES LTD AIR ZIMBABWE CORPORATION TRANSAERO AIRLINE DIRECT AIR BAHAMASAIR U.S.AIR ALLEGHENY AIRLINES FLORIDA GULF AIRLINES PIEDMONT AIRLINES INC P.S.A. AIRLINES USAIR EXPRESS UNION DE TRANSPORTS AERIENS AIR AUSTRAL AIR EUROPA CAMEROON AIRLINES VIASA BIRMINGHAM EXECUTIVE AIRWAYS. SERVIVENS...VENEZUELA AEROVIAS VENEZOLANAS AVENSAS VLM ROYAL.AIR.CAMBODGE REGIONAL AIRLINES VIETNAM AIRLINES TYROLEAN.AIRWAYS VIACAO AEREA SAO PAULO SA.VASP TRANSPORTES.AEREOSDECABO.VERDE VIRGIN ATLANTIC AIRWAYS AIR TAHITI AIR IVOIRE AEROSVIT AIRLINES AIRTOURS.INT,L.GUERNSEY. WESTERN PACIFIC AIRLINES WARDAIR CANADA (1975) LTD. CHALLENGE AIR CARGO INC WIDEROE,S FLYVESELSKAP CHINA NORTHWEST AIRLINES SOUTHWEST AIRLINES WORLD AIRWAYS INC. ALOHA ISLANDAIR WESTERN AIR LINES INC. NIGERIA AIRWAYS LTD AIR.SOUTH CITYJET OMAN AVIATION SERVICES BERLIN EUROPEAN U.K.LTD. CRONUS AIRLINES IATA SINGAPORE LOT GROUND SERVICES LTD. ITR TURBORREACTORES S.A. DE CV IATA MIAMI IATA GENEVE GULF AIRCRAFT MAINTENANCE CO. ACCA C.A.L. CARGO AIRLINES LTD. UNIVERSAL AIR TRAVEL PLAN UATP AIR TRANSPORT ASSOSIATION AUSTRALIAN AIR EXPRESS SITA XS 950 AIR.EXEL.NETHERLANDS PRESIDENTIAL AIRWAYS INC. FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES PTY LTD. CYPRUS.TURKISH.AIRLINES HELI.AIR.MONACO AERO LLOYD LUFTVERKEHRS-AG SKYWEST.AIRLINES MESA AIRLINES INC AIR.NOSTRUM.L.A.M.S.A STATE WEST AIRLINES MIDWEST EXPRESS AIRLINES. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

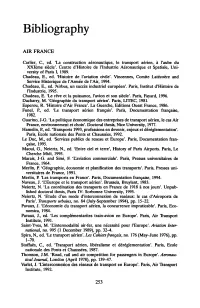

Bibliography

Bibliography AIR FRANCE Carlier, c., ed. 'La construction aeronautique, Ie transport aenen, a I'aube du XXIeme siecle'. Centre d'Histoire de l'Industrie Aeronautique et Spatiale, Uni versity of Paris I, 1989. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Histoire de I'aviation civile'. Vincennes, Comite Latecoere and Service Historique de l'Annee de l'Air, 1994. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Airbus, un succes industriel europeen'. Paris, Institut d'Histoire de l'Industrie, 1995. Chadeau, E. 'Le reve et la puissance, I'avion et son siecle'. Paris, Fayard, 1996. Dacharry, M. 'Geographie du transport aerien'. Paris, LITEC, 1981. Esperou, R. 'Histoire d'Air France'. La Guerche, Editions Ouest France, 1986. Funel, P., ed. 'Le transport aerien fran~ais'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1982. Guarino, J-G. 'La politique economique des entreprises de transport aerien, Ie cas Air France, environnement et choix'. Doctoral thesis, Nice University, 1977. Hamelin, P., ed. 'Transports 1993, professions en devenir, enjeux et dereglementation'. Paris, Ecole nationale des Ponts et Chaussees, 1992. Le Due, M., ed. 'Services publics de reseau et Europe'. Paris, Documentation fran ~ise, 1995. Maoui, G., Neiertz, N., ed. 'Entre ciel et terre', History of Paris Airports. Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 1995. Marais, J-G. and Simi, R 'Caviation commerciale'. Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1964. Merlin, P. 'Geographie, economie et planification des transports'. Paris, Presses uni- versitaires de France, 1991. Merlin, P. 'Les transports en France'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1994. Naveau, J. 'CEurope et Ie transport aerien'. Brussels, Bruylant, 1983. Neiertz, N. 'La coordination des transports en France de 1918 a nos jours'. Unpub lished doctoral thesis, Paris IV- Sorbonne University, 1995. -

Current Issues in Aircraft Finance

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 56 | Issue 4 Article 4 1991 Current Issues in Aircraft inF ance Michael Downey Rice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Michael Downey Rice, Current Issues in Aircraft iF nance, 56 J. Air L. & Com. 1027 (1991) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol56/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CURRENT ISSUES IN AIRCRAFT FINANCE MICHAEL DOWNEY RICE* THE AIRLINE BUSINESS is capital-intensive. The price list at Boeing or McDonnell-Douglas starts at about $25 million for a twin-engine, narrow-body aircraft, and goes up to approximately $130 million for a wide- body aircraft capable of transcontinental travel. At that, the order books are full, and commercial transport sales of United States manufacturers are expected to exceed $30 billion in 1991. The trend continues upward.' Under these circumstances, the airline capital budget- ing process, particularly the aircraft financing process, de- serves a careful analysis. A difference of a few basic points in financing costs has enormous significance in a hundred million dollar transaction. Achieving the optimum fi- nancing arrangements is a complex and not entirely quan- titative exercise. The needs and desires of the financing parties-banks, insurance companies, pension plans, and other institutional investors-deserve as much analysis as net present values and internal rates of return. -

BURLINGTON AIRPORT COMMISSION December 1, 1983

MINUTES BURLINGTON AIRPORT COMMISSION December 1, 1983 PRESENT: William P. Thompson, Chairman M. Robert Blanchard Vincent J. D’Acuti Schuyler Jackson Walter E. Houghton, Director of Aviation Kathy A. Gleason, Office Manager/Clerk ABSENT: Gary H. Barnes Mr. Houghton requested the agenda be amended to include Reports item 5d., Shoe Shine Parlor Proposal and Resolutions item 4, Month to Month Lease of Building #865 “White House”. Mr. D’Acuti moved to amend the agenda accordingly and add Reports item number 6 by Mr. D’Acuti on issues with the City of South Burlington and discussion relative to the Christmas Party. Mr. Jackson seconded the motion and requested discussion of the Christmas Party be handled in Executive Session. All were in favor. MONTHLY REPORTS 1. On motion of Mr. Blanchard, seconded by Mr. D’Acuti, the Minutes of the November 3, 1983 Commission Meeting were approved as submitted. All were in favor. 2. Following examination of the Warrant for the month of November, Mr. D’Acuti moved for approval. Mr. Blanchard seconded the motion and all were in favor. 3. With review of the Operating Statements, Mr. Jackson expressed his concern with all receivable accounts listed as thirty to sixty days old. He stated that enough time has been wasted in an effort to instill responsibility for timely payments and moved Mr. Houghton be authorized to devise a program which upon culmination, all accounts with tenants and airport users will be current. Mr. Blanchard seconded the motion and all were infavor. Mr. D’Acuti moved to approve the Operating Statements as presented, seconded by Mr. -

RCED-90-147 Airline Competition

All~lISI l!t!)o AIRLINE COMPETITION Industry Operating and Marketing Practices Limit Market Entry -- ~~Ao//I~(::I’:I~-~o-lri7 ---- “._ - . -...- .. ..._ __ _ ..”._._._.__ _ .““..ll.l~,,l__,*” _~” _.-. Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-236341 August 29,lQQO The Honorable John C. Danforth Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate The Honorable Jack Brooks Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives In response your requests, this report provides information on how various airline industry operating and marketing practices limit entry into the deregulated airline industry and how they affect competition in that industry. Specifically, we identified two major types of . barriers. The first type is created by the unavailability of the airport facilities and operating rights an airline must have in order to begin or expand service at an airport. The second type is created by airline marketing practices that have come into widespread use since deregulation. As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce its contents earlier, we plan no further distribution of this report until 30 days from the date of this letter. At that time, we will send copies to the Secretary of the Department of Transportation; the Administrator, Federal Aviation Administration; and interested congressional committees. We will also make copies available to others upon request. If you have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 276-1000. Major contributors to this report are listed in appendix XIII. Kenneth M. Mead Director, Transportation Issues . , Executive Summary When the Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act in 1978, it Purpose sought to foster competition so as to promote lower fares and good ser- vice.