A Prospective Open-Labeled Trial with Levetiracetam in Pediatric Epilepsy Syndromes: Continuous Spikes and Waves During Sleep Is Definitely a Target

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

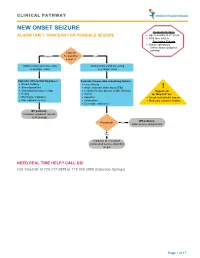

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

The Relationship Between the Components of Idiopathic Focal Epilepsy

Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care Review Article Open Access The relationship between the components of idiopathic focal epilepsy Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The classification of epileptic syndromes in children is not a simple duty, it requires Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon a great clinical ability as well as some degree of experience. Until today there is no Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of international consensus regarding the different diseases that are part of the Idiopathic Copenhagen, Denmark Focal Epilepsies However, these diseases are the most prevalent in children suffering from some type of epilepsy, for this reason it is important to know more about these, Correspondence: Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon their clinical characteristics, pathological findings in studies such as encephalogram, M.D., Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology Faculty resonance, polysomnography and others. In the same way, to explore the possible of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, genetic origins of many of these pathologies, that have been little explored and Denmark, Jagtev 160, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark, become an important therapeutic goal. A description of the most relevant aspects of Email [email protected] atypical benign partial epilepsy, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, electrical status epilepticus during sleep and Panayiotopoulos Received: February 17, 2018 | Published: May 14, 2018 syndrome is presented in this review, Allowing physicians and family members of children suffering from these diseases to have a better understanding and establish in this way a better diagnosis and treatment in patients, as well as promote in the scientific community the interest to investigate more about these relevant pathologies in childhood. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Prospective Evaluation of Interrater Agreement Between EEG Technologists and Neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prospective evaluation of interrater agreement between EEG technologists and neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S. Reif1,2,3, Nora Sterlepper1,2, Felix Rosenow1,2 & Adam Strzelczyk 1,2* We aim to prospectively investigate, in a large and heterogeneous population, the electroencephalogram (EEG)-reading performances of EEG technologists. A total of 8 EEG technologists and 5 certifed neurophysiologists independently analyzed 20-min EEG recordings. Interrater agreement (IRA) for predefned EEG pattern identifcation between EEG technologists and neurophysiologits was assessed using percentage of agreement (PA) and Gwet-AC1. Among 1528 EEG recordings, the PA [95% confdence interval] and interrater agreement (IRA, AC1) values were as follows: status epilepticus (SE) and seizures, 97% [96–98%], AC1 kappa = 0.97; interictal epileptiform discharges, 78% [76–80%], AC1 = 0.63; and conclusion dichotomized as “normal” versus “pathological”, 83.6% [82–86%], AC1 = 0.71. EEG technologists identifed SE and seizures with 99% [98–99%] negative predictive value, whereas the positive predictive values (PPVs) were 48% [34– 62%] and 35% [20–53%], respectively. The PPV for normal EEGs was 72% [68–76%]. SE and seizure detection were impaired in poorly cooperating patients (SE and seizures; p < 0.001), intubated and older patients (SE; p < 0.001), and confrmed epilepsy patients (seizures; p = 0.004). EEG technologists identifed ictal features with few false negatives but high false positives, and identifed normal EEGs with good PPV. The absence of ictal features reported by EEG technologists can be reassuring; however, EEG traces should be reviewed by neurophysiologists before taking action. -

Panayiotopoulos Syndrome: a Debate

Letter to the Editor Epileptic Disord 2010; 12 (1): 91-4 Panayiotopoulos syndrome: a debate To the editor superbly illustrated by the syndrome of benign partial Yalcin et al. (2009) describe three patients with neuro- epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes, a syndrome that radiological abnormalities identifi ed on magnetic has robustly defi ed eponymous adoption for many resonance imaging (MRI), which they consider to be decades. “coincidental” and un-related to an underlying electro- clinical diagnosis of Panayiotopoulos syndrome Richard E. Appleton, Brian Tedman, (PS). While they propose that the MRI abnormalities Teresa Preston, Tam Foy demonstrated are coincidental and do not preclude The Roald Dahl EEG Department, the diagnosis of PS, there may be another explana- Paediatric Neurosciences Foundation Trust, tion. It could reasonably be argued that the radiolog- Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, ical abnormalities seen in their patients (particularly Liverpool L12 2AP, UK patients 2 and 3) are not coincidental and that these <[email protected]> patients have a symptomatic focal or multifocal epilepsy and not Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Response to the letter of R. Appleton, et al. Although an “expert consensus” has attempted to To the editor defi ne and classify the existence of PS (Ferrie et al., 2006), it does not necessarily follow that their opinion We welcome the comments of Appleton and his is correct. There appear to be ever-increasing reports colleagues regarding issues raised for a better under- of “atypical” cases of PS. On scientifi c grounds this standing of Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS). must surely raise the question as to whether this does The authors argue that the 3 children we described represent a true “syndrome” as defi ned in both the had symptomatic focal or multifocal epilepsy not PS. -

Brain MRI-DTI Findings in a Patient with Possible Panayiotopoulos

Gaddam Diffusion Tensor imaging findings in a patient with Panayiotopoulos syndrome Satish Gaddam MD, Rosario Maria Riel-Romero MD*, Eduardo C. Gonzalez-Toledo MD, PhD** Departments of Neurology, Pediatrics*, Radiology**, and Anesthesiology** Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Shreveport, LA Introduction: Panayitopoulos syndrome or benign epilepsy with occipital paroxysms is a common benign epilepsy syndrome described in children. Patients generally have infrequent seizures, mainly occurring at night with multitude of autonomic symptoms such as emesis, pallor, tachycardia and visual hallucinations. Inter-ictal EEG findings most commonly demonstrate nearly continuous unilateral or bilateral high voltage spike-wave discharges from the occipital or posterior temporal regions. We present a patient with clinical symptoms and electroencephalographic (EEG) findings consistent with Panayitopoulos syndrome and diffusion tensor imaging of her brain showing attenuation of fibers over the right temporal-occipital area and decreased thickness of the right occipital lobe. Previous scientific literature on Panayitopoulos syndrome has discussed the brain MRI and functional MRI findings. However, to the best of our knowledge, diffusion tensor studies in patients with Panayiotopoulos syndrome have not been reported. Our case report suggests that subtle structural lesions may be a part of the pathophysiology of Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Case report: A 6-year-old right-handed previously healthy Caucasian female woke up one night, after being asleep for about an hour, and told her father that she had a bad dream. She was retching and vomited out partially digested food. Her father described her as staring and unresponsive with a dazed, confused look in her eyes. The episode lasted for about 30 minutes and she had incoherent speech for about an hour. -

Overview of the Epilepsies of Childhood and Comorbidities

Overview of the epilepsies of childhood and comorbidities Dr Amy McTague BRC Catalyst Fellow/Honorary Consultant Paediatric Neurologist UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health Epilepsy • is a common condition – prevalence 0.5% • is not a single condition • can be difficult to diagnose • no single treatment • misdiagnosis rate is high • 25% resistant to medication • more likely if lesional • surgical treatment may be an option if localised onset to seizures Definition of epilepsy ILAE, Fisher et al Epilepsia 2005, 2014 a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures. Epilepsy: A disease of the brain 1. At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart; 2. One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years 3. Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. Definition of a seizure A transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain ILAE 2005 Generalised seizures • Originate at some point within and rapidly engage bilaterally distributed networks • Can include cortical and subcortical structures but not necessarily the entire cortex Focal seizures • Originate within networks limited to one hemisphere • May be discretely localized or more widely distributed.… ILAE 2017 Classification of Seizure Types Expanded Version 1 Focal Onset Generalized Onset Unknown Onset -

Pediatric Epilepsy

PEDIATRIC EPILEPSY Ø Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic neurological disorders. It is characterized by recurrent unprovoked seizures or an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures. If epilepsy begins in childhood, it is often outgrown. Seizures are common in childhood and adolescence. Approximately 3% of children will experience a seizure. Ø A seizure occurs when there is a sudden change in behavior or sensation caused by abnormal and excessive electrical hypersynchronization of neuronal networks in the cerebral cortex. Normal inhibition is overcome by excessive excitatory stimuli. Ø If the cause of the seizures is known (for example: genetic, inborn errors of metabolism, metabolic (eg: low glucose, electrolyte abnormalities), structural (eg: malformations, tumours, bleeds, stroke, traumatic brain injury), infectious, inflammatory, or toxins) it is classified as symptomatic. If the cause is unknown, it is classified as idiopathic. 1. WHERE DID THE SEIZURE START? / WHAT KIND OF SEIZURE IS IT? 2. IS AWARENESS YES FOCAL ONSET GENERALIZED UNKNOWN IMPAIRED? NO Seizure that originates ONSET ONSET in a focal cortical area Seizure that involves When it is unclear YES with associated clinical both sides of the where the seizure 3. PROGRESSION TO BILATERAL? features. brain from the onset. starts. NO SEIZURE SEMIOLOGY (The terminology for seizure types is designed to be useful for communicating the key characteristics of seizures) CLONIC: sustained rhythmical TONIC: muscles stiffen or ATONIC: sudden loss of muscle tone, MYOCLONUS: sudden lighting- jerking movements. tense. lasting seconds. like jerk, may cluster. EPILEPTIC SPASM: sudden AUTONOMIC: eg: AUTOMATISMS: ABSENCE: brief (≤ 10s), OTHERS: change flexion, extension, or flexion- rising epigastric stereotyped, purposeless frequent (up to 100’s) in cognition, extension of proximal and sensations, waves of movements. -

Benign Childhood Seizure Susceptibility Syndromes

Chapter 9 Benign childhood seizure susceptibility syndromes MICHALIS KOUTROUMANIDIS and CHRYSOSTOMOS PANAYIOTOPOULOS Department of Clinical Neurophysiology and Epilepsies, St Thomas’ Hospital, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London ___________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Benign childhood focal seizures and related idiopathic epileptic syndromes affect 25% of children with non-febrile seizures and constitute a significant part of the everyday practice of paediatricians, neurologists and electroencephalographers. They comprise three identifiable electroclinical syndromes recognised by the International League against Epilepsy (ILAE)1: rolandic epilepsy which is well known; Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS), a common autonomic epilepsy, which is currently more readily diagnosed; and the idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (ICOE-G) including the idiopathic photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy, a less common form with uncertain prognosis. There are also reports of children with benign focal seizures of predominantly affective symptoms, and claims have been made for other clinical phenotypes associated with specific inter-ictal EEG foci, such as frontal, midline or parietal, with or without giant somatosensory evoked spikes (GSES). Neurological and mental states and brain imaging are normal, though because of their high prevalence any type of benign childhood focal seizures may incidentally occur in children with neurocognitive deficits or abnormal brain scans. The most useful diagnostic test is the EEG. In clinical practice, the combination of a normal child with infrequent seizures and an EEG showing disproportionately severe spike activity is highly suggestive of these benign childhood syndromes2. All these conditions may be linked together in a broad, age-related and age-limited, benign childhood seizure susceptibility syndrome (BCSSS) which may be genetically determined3. -

Epileptic Syndromes in Childhood. a Practical Approach

Submitted on: 03/10/2018 Approved on: 05/26/2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Epileptic Syndromes in Childhood. A Practical Approach Paulo Breno Noronha Liberalesso1 Keywords: Abstract Epilepsy, Epileptic seizures are among the most frequent severe childhood neurological diseases and are defined as a transient, Diagnosis, paroxysmal and involuntary event manifested by motor, sensory, autonomic and psychic signs, with or without Therapeutics, alteration of consciousness, caused by synchronous and excessive neuronal activity in brain. Epilepsy is a brain disease Treatment Outcome. characterized by (a) at least two unprovoked epileptic seizures or two reflex seizure at a minimum interval of 24 hours; or (b) an epileptic seizure or reflex seizure and risk of a new event estimated at least 60%; or (c) diagnosis of an epileptic syndrome. This article aims to review the main diagnoses and therapeutics of the most frequent epilepsy syndromes of the childhood and adolescence. 1 Doctor at the Department of Pediatric Neurology and Epilepsy Laboratory of Pequeno Príncipe Hospital. Correspondence to: Mariana Mundin da Rocha. Departamento de Neurologia Pediátrica do Hospital Pequeno Príncipe. Rua Mauá, nº 719, Apartamento 202. Torre A. Bairro Alto da Glória. Curitiba. Paraná. Brasil. CEP: 80030-200. Residência Pediátrica 2018;8(supl 1):56-63 DOI: 10.25060/residpediatr-2018.v8s1-10 56 INTRODUCTION diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome.”3 The criteria of 60% recurrence risk and initiating treatment Seizures have been reported in ancient societies for after the second seizure have been adopted according to an over 5,000 years. Before the Christian Era, seizures used to be important study published nearly 20 years ago, which showed attributed to demonic possession, divine punishment, or the that, after the first unprovoked seizure, the maximum recurrence influence of celestial objects, as reported in the Biblical Gospels risk reached 40% in 5 years; after the second seizure, this risk of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. -

Neurologic Disease and Common Sleep Comorbidities

Neurologic Disease and Common Sleep Comorbidities • Stephen Nelson, MD, PhD, FAACPDM, FAAN, FAAP, FANA • Professor of Pediatrics, Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry • Epileptologist • Section Head, Tulane University School of Medicine • CHNOLA Pediatric Neurology Disclosure slide All opinions are mine, and are based on my knowledge, training and expertise. I do not represent Tulane University, CHNOLA, the AAP, or any other organization with these opinions. It is my obligation to disclose to you (the audience) that I am on the Speakers Bureaus for BioMarin and Supernus. However, I acknowledge that today’s activity is certified for CME credit and thus cannot be promotional. I will give a balanced presentation using the best available evidence to support my conclusions and recommendations. I do not intend to discuss an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device in my presentation. Epilepsy and sleep • Improvements in sleep can improve epilepsy • Both sleep deprivation and oversleeping can provoke seizures • Epilepsy patients at increased risk for co-morbid sleep disorders • Seizures - more likely during non-REM sleep (especially N1/N2) • Interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) more frequent in non-REM sleep (especially N3) so better estimate of seizure risk • REM sleep protective, and thus better for localization of IED Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS or Rolandic epilepsy) • One of the most common forms of epilepsy in children (8-20%) • 75% start between 7 - 10 years (range 1 – 14) • Seizures -

Rolandic Epilepsy Or Panayiotopoulos Syndrome?

Original article Epileptic Disord 2003; 5: 139-43 Children with Rolandic spikes and ictal vomiting: Rolandic epilepsy or Panayiotopoulos syndrome? Athanasios Covanis, Christina Lada, Konstantinos Skiadas Received January 31, 2003; Accepted June 5, 2003 ABSTRACT − Centrotemporal spikes are the EEG marker of Rolandic epilepsy, while ictus emeticus is one of the main seizure manifestations of Panayiotopou- los syndrome. Ictus emeticus has not been reported in Rolandic epilepsy. Out of a population of 1340 children with focal afebrile seizures we studied 24 chil- dren who had emetic manifestations in at least one seizure and centrotemporal spikes in at least one EEG. They were of normal neurological status and had a follow-up of at least two years after the last seizure. All children had sleep EEG following sleep deprivation. Two groups of patients were identified. Group A (12 patients) with EEG centrotemporal spikes only and group B (12 patients) with centrotemporal spikes and spikes in other locations. In 21 patients, ictal emetic manifestations culminated in vomiting and in three only nausea or retching occurred. The commonest presentation was ictus emeticus at onset followed by deviation of the eyes or staring, loss of contact and floppiness. In 79%, seizures occurred during sleep. Autonomic status epilepticus occurred in 37.5%. The mean age at onset was 5.3 years. Overall analysis of the clinical and EEG data points out that the vast majority of these patients primarily suffer from Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Twenty patients (83%) had ictal semiology typical of Panayiotopoulos syndrome, but five also had concurrent Rolandic symptoms and four later developed pure Rolandic seizures.