Overview of the Epilepsies of Childhood and Comorbidities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Use Anti-Epileptic Drugs Wisely ?

When to start and how to select antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) Dr. Chusak Limotai, MD., M.Sc., CSCN(C) Talk overview • When to start treatment ? • Which drug ? • Monotherapy • Combining AEDs (Rational polytherapy) • Old AEDs versus new AEDs • Drug level monitoring • When to discontinue AEDs ? When to start treatment ? • Correct diagnosis • Generally start after the second unprovoked seizure – First unprovoked seizure: A seizure or flurry of seizures or occurring within 24 hrs in the person > 1 month old of age – Epilepsy: 2 or more epileptic seizures occur unprovoked by any immediately identifiable cause ILAE 2014 • A person is considered to have epilepsy if they meet any of the following conditions. 1) At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring greater than 24 hours apart. 2) One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years. 3) Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome – Epilepsy is considered to be resolved for individuals who had an age- dependent epilepsy syndrome but are now past the applicable age or those who have remained seizure-free for the last 10 years, with no seizure medicines for the last 5 years. Fisher RS et al. A practical clinical definition of epilepsy, Epilepsia 2014; 55:475-482 Cumulative risk of recurrence after a first unprovoked seizure 67% at 1 yr 78% at 3 yrs 44 % at 3 yrs 60% at 6 mo 32% at 3 yrs 17% at 3 yrs Hart YM et.al; The Lancet 1990 Indications to consider antiepileptic drug treatment after the first seizure Pohlmann-Eden B et.al BMJ 2006 Seneviratne U Postgrad Med J 2009 Factors associated with increased/lower risk • Increased risk: • Lower risk: – Adolescence onset – seizure occurred within – associated neurological 3 mo after acute insult deficits e.g. -

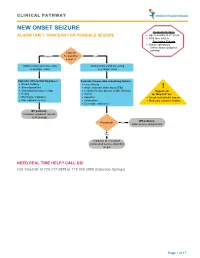

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Genetics-Of-Epilepsy.Pdf

logy & N ro eu u r e o N p h f Bamikole, et al., J Neurol Neurophysiol 2019, 10:3 y o s l i o a n l o r g u y o J Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology ISSN: 2155-9562 Review Open Access Genetics of Epilepsy Oluwayemi Joshua Bamikole *, Miles-Dei Benedict Olufeagba, Samuel Temitope Soge, Noah Olamide Bukoye, Taiwo Habeeb Olajide, Subulade Abigail Ademola, Olukemi Kehinde Amodu Institute of Child Health, University of Ibadan. Nigeria *Corresponding author: Oluwayemi Joshua Bamikole, Institute of Child Health, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, Tel: +2347068505498; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 06, 2019; Accepted date: March 27, 2019; Published date: August 09, 2019 Copyright: © 2019 Oluwayemi Joshua Bamikole. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Genetics is a branch of the human biology that provides insights into basic and vital processes which arise from birth till death, development to apoptosis (cell death), and in disease aetiology and therapies, or better methods in use of available treatments to solve human health conditions because genes function in all biological process. Epilepsy is a seizure that occurs without identifiable justification with a great chance of further seizures which is almost the same to the global recurrence risk of 60% after two unjustified seizures, happening over a ten years’ span. Fifty million people globally present with epilepsy ranging from about 20 to 70 cases per 100,000 in a year and Over 85% of the epilepsy cases are present in underdeveloped and even developing countries with low or middle income. -

The Relationship Between the Components of Idiopathic Focal Epilepsy

Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care Review Article Open Access The relationship between the components of idiopathic focal epilepsy Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The classification of epileptic syndromes in children is not a simple duty, it requires Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon a great clinical ability as well as some degree of experience. Until today there is no Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of international consensus regarding the different diseases that are part of the Idiopathic Copenhagen, Denmark Focal Epilepsies However, these diseases are the most prevalent in children suffering from some type of epilepsy, for this reason it is important to know more about these, Correspondence: Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon their clinical characteristics, pathological findings in studies such as encephalogram, M.D., Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology Faculty resonance, polysomnography and others. In the same way, to explore the possible of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, genetic origins of many of these pathologies, that have been little explored and Denmark, Jagtev 160, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark, become an important therapeutic goal. A description of the most relevant aspects of Email [email protected] atypical benign partial epilepsy, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, electrical status epilepticus during sleep and Panayiotopoulos Received: February 17, 2018 | Published: May 14, 2018 syndrome is presented in this review, Allowing physicians and family members of children suffering from these diseases to have a better understanding and establish in this way a better diagnosis and treatment in patients, as well as promote in the scientific community the interest to investigate more about these relevant pathologies in childhood. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants INTRODUCTION • Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following (Fisher et al 2014): At least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart; 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least ○ 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; ○ Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. • Types of seizures include generalized seizures, focal (partial) seizures, and status epilepticus (Centers for Disease Control○ and Prevention [CDC] 2018, Epilepsy Foundation Greater Chicago 2020). Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and include: . Tonic-clonic (grand mal): begin with stiffening of the limbs, followed by jerking of the limbs and face ○ . Myoclonic: characterized by rapid, brief contractions of body muscles, usually on both sides of the body at the same time . Atonic: characterized by abrupt loss of muscle tone; they are also called drop attacks or akinetic seizures and can result in injury due to falls . Absence (petit mal): characterized by brief lapses of awareness, sometimes with staring, that begin and end abruptly; they are more common in children than adults and may be accompanied by brief myoclonic jerking of the eyelids or facial muscles, a loss of muscle tone, or automatisms. Focal seizures are located in just 1 area of the brain and include: . Simple: affect a small part of the brain; can affect movement, sensations, and emotion, without a loss of ○ consciousness . Complex: affect a larger area of the brain than simple focal seizures and the patient loses awareness; episodes typically begin with a blank stare, followed by chewing movements, picking at or fumbling with clothing, mumbling, and performing repeated unorganized movements or wandering; they may also be called “temporal lobe epilepsy” or “psychomotor epilepsy” . -

A Prospective Open-Labeled Trial with Levetiracetam in Pediatric Epilepsy Syndromes: Continuous Spikes and Waves During Sleep Is Definitely a Target

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Seizure 20 (2011) 320–325 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seizure journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yseiz A prospective open-labeled trial with levetiracetam in pediatric epilepsy syndromes: Continuous spikes and waves during sleep is definitely a target S. Chhun a,b,c, P. Troude d, N. Villeneuve e, C. Soufflet a,b,f, S. Napuri g, J. Motte h, F. Pouplard i, C. Alberti d, S. Helfen j, G. Pons a,b,c, O. Dulac a,b,k, C. Chiron a,b,k,* a Inserm, U663, Paris, France b University Paris Descartes, Faculty of Medicine, Paris, France c APHP, Pediatric Clinical Pharmacology, Cochin-Saint Vincent de Paul Hospital, Paris, France d APHP, Unit of Clinical Research, Robert Debre Hospital, Paris, France e APHM, Neuropediatric Department, Marseille, France f APHP, Necker Hospital, Department of Functional Explorations, Paris, France g Neuropediatric Department, Rennes Hospital, France h Neuropediatric Department, American Memorial Hospital, Reims, France i Neuropediatric Department, Angers Hospital, France j APHP, Necker Hospital, Unit of Clinical Research, Paris, France k APHP, Necker Hospital, Neuropediatric Department, Paris, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Although LVT is currently extensively prescribed in childhood epilepsy, its effect on the panel of Received 12 October 2010 refractory epilepsy syndromes has not been entirely evaluated prospectively. In order to study the Received in revised form 17 December 2010 efficacy and safety of LVT as adjunctive therapy according to syndromes, we included 102 patients with Accepted 27 December 2010 refractory seizures (6 months to 15 years) in a prospective open-labeled trial. -

Prospective Evaluation of Interrater Agreement Between EEG Technologists and Neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prospective evaluation of interrater agreement between EEG technologists and neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S. Reif1,2,3, Nora Sterlepper1,2, Felix Rosenow1,2 & Adam Strzelczyk 1,2* We aim to prospectively investigate, in a large and heterogeneous population, the electroencephalogram (EEG)-reading performances of EEG technologists. A total of 8 EEG technologists and 5 certifed neurophysiologists independently analyzed 20-min EEG recordings. Interrater agreement (IRA) for predefned EEG pattern identifcation between EEG technologists and neurophysiologits was assessed using percentage of agreement (PA) and Gwet-AC1. Among 1528 EEG recordings, the PA [95% confdence interval] and interrater agreement (IRA, AC1) values were as follows: status epilepticus (SE) and seizures, 97% [96–98%], AC1 kappa = 0.97; interictal epileptiform discharges, 78% [76–80%], AC1 = 0.63; and conclusion dichotomized as “normal” versus “pathological”, 83.6% [82–86%], AC1 = 0.71. EEG technologists identifed SE and seizures with 99% [98–99%] negative predictive value, whereas the positive predictive values (PPVs) were 48% [34– 62%] and 35% [20–53%], respectively. The PPV for normal EEGs was 72% [68–76%]. SE and seizure detection were impaired in poorly cooperating patients (SE and seizures; p < 0.001), intubated and older patients (SE; p < 0.001), and confrmed epilepsy patients (seizures; p = 0.004). EEG technologists identifed ictal features with few false negatives but high false positives, and identifed normal EEGs with good PPV. The absence of ictal features reported by EEG technologists can be reassuring; however, EEG traces should be reviewed by neurophysiologists before taking action. -

Diaper Changing-Induced Reflex Seizures in CDKL5-Related Epilepsy

Journal Identification = EPD Article Identification = 0999 Date: October 25, 2018 Time: 4:24 pm Clinical commentary Epileptic Disord 2018; 20 (5): 428-33 Diaper changing-induced reflex seizures in CDKL5-related epilepsy Roberta Solazzi 1, Elena Fiorini 1, Elena Parrini 2, Francesca Darra 1, Bernardo Dalla Bernardina 1, Gaetano Cantalupo 1 1 Child Neuropsychiatry, Department of Surgical Sciences, Dentistry, Gynecology and Pediatrics, University of Verona 2 Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Pediatric Neurology Unit, Children’s Hospital A. Meyer, Florence, Italy Received March 26, 2018; Accepted July 22, 2018 ABSTRACT – Mutations in the CDKL5 (cyclin-dependent kinase-like-5) gene are known to determine early-onset drug resistant epilepsies and severe cognitive impairment with absent language, hand stereotypies, and decel- eration of head growth. Reflex seizures are epileptic events triggered by specific stimuli and diaper changing is a very rare triggering event, previ- ously described in individual cases of both focal and unclassified epilepsy, as well as in Dravet syndrome. Our aim was to describe diaper changing- induced reflex seizures as one of the presenting features in a case of CDKL5-related epilepsy, providing video-EEG documentation and focusing discussion on hyperexcitability determined by the disease. [Published with video sequence on www.epilepticdisorders.com] Key words: reflex seizure, diaper changing-induced reflex seizure, rub epilepsy, CDKL5-related encephalopathy CDKL5 is a gene located on chro- infantile spasms and myoclonic mosome Xp22, which encodes encephalopathy (Guerrini and cyclin-dependent kinase-like-5, a Parrini, 2012; Fehr et al., 2016). protein implicated in neuronal Reflex seizures are epileptic events development and morphogenesis, triggered by specific stimulation whose the precise functions remain (motor, sensory or cognitive), fre- unknown. -

Classification of Epilepsy: What's New? A/Professor Annie

Classification of Epilepsy: What’s new? A/Professor Annie Bye The following material on the new epilepsy classification is based on the following 3 papers: . Scheffer et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia, 58(4): 512-521,2017. Fisher et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia, 2017, 58(4): 522-530 . Fisher et al. Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types. Epilepsia, 58(4): 531-542, 2017. Proposal for a Framework for Epilepsy Classification and Diagnosis Allows diagnosis at multiple levels Classification is primarily for clinical purposes and is relevant in all environments. Inherently dynamic Operational (practical) definition of Epilepsy. ILAE, 2014 Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following conditions: 1. At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring >24h apart. 2. One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years. 3. Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. Epilepsy Resolved Epilepsy is now considered resolved for individuals who had an age-dependent epilepsy syndrome but are now past the applicable age Or those who have remained seizure free for past 10 years with no seizure medicines for last 5 years. Framework for epilepsy classification. Epilepsia 2017,58(4)512-21 Framework of Epilepsy classification First Step : What is the seizure type? Mode of seizure onset and classification of seizures. -

Panayiotopoulos Syndrome: a Debate

Letter to the Editor Epileptic Disord 2010; 12 (1): 91-4 Panayiotopoulos syndrome: a debate To the editor superbly illustrated by the syndrome of benign partial Yalcin et al. (2009) describe three patients with neuro- epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes, a syndrome that radiological abnormalities identifi ed on magnetic has robustly defi ed eponymous adoption for many resonance imaging (MRI), which they consider to be decades. “coincidental” and un-related to an underlying electro- clinical diagnosis of Panayiotopoulos syndrome Richard E. Appleton, Brian Tedman, (PS). While they propose that the MRI abnormalities Teresa Preston, Tam Foy demonstrated are coincidental and do not preclude The Roald Dahl EEG Department, the diagnosis of PS, there may be another explana- Paediatric Neurosciences Foundation Trust, tion. It could reasonably be argued that the radiolog- Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, ical abnormalities seen in their patients (particularly Liverpool L12 2AP, UK patients 2 and 3) are not coincidental and that these <[email protected]> patients have a symptomatic focal or multifocal epilepsy and not Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Response to the letter of R. Appleton, et al. Although an “expert consensus” has attempted to To the editor defi ne and classify the existence of PS (Ferrie et al., 2006), it does not necessarily follow that their opinion We welcome the comments of Appleton and his is correct. There appear to be ever-increasing reports colleagues regarding issues raised for a better under- of “atypical” cases of PS. On scientifi c grounds this standing of Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS). must surely raise the question as to whether this does The authors argue that the 3 children we described represent a true “syndrome” as defi ned in both the had symptomatic focal or multifocal epilepsy not PS. -

2016-ACP-Review-Epilepsy.Pdf

Annals of Internal Medicineᮋ In the Clinic® Diagnosis Epilepsy Prevention n epileptic seizure is defined by the Inter- Treatment national League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Aas “a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or syn- Further Considerations chronous neuronal activity in the brain” (1). In 2014, the ILAE provided an operational (practi- cal) clinical definition of epilepsy as a disease of the brain defined as any of the following condi- tions: at least 2 unprovoked [or reflex] seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart; 1 unpro- voked [or reflex] seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recur- rence risk [at least 60%] after 2 unprovoked sei- zures, occurring over the next 10 years; [and/or] a diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome (2). The CME quiz is available at www.annals.org/intheclinic.aspx. Complete the quiz to earn up to 1.5 CME credits. Physician Writer doi:10.7326/AITC201602020 Kaarkuzhali B. Krishnamurthy, MD CME Objective: To review current evidence for diagnosis, prevention, treatment, and further considerations of epilepsy. Funding Source: American College of Physicians. Disclosures: Dr. Krishnamurthy, ACP Contributing Author, has disclosed no conflicts of interest. Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterest Forms.do?msNum=M15-2484. With the assistance of additional physician writers, the editors of Annals of Internal Medicine develop In the Clinic using MKSAP and other resources of the American College of Physicians. In the Clinic does not necessarily represent official ACP clinical policy. For ACP clinical guidelines, please go to https://www.acponline.org/clinical_information/guidelines/.