Rolandic Epilepsy Or Panayiotopoulos Syndrome?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pediatric Epilepsy Clips by Pediatric Elizabeth Medaugh, MSN, CPNP-PC , Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Neurology

Nursing May 2016 Pediatric Clips Pediatric Nursing Pediatric Epilepsy Clips by Pediatric Elizabeth Medaugh, MSN, CPNP-PC , Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Neurology Advanced Practice Sophia had been exceeding down to sleep, mother heard a Nurses at Dayton Case Study the expectations of school. thump and went to check on her. Her teachers report her being Sophia’s eyes were wide open Children’s provides Sophia is a 7 year old Caucasian focused the first two quarters, and deviated left, left arm was quick reviews of female who presented to her but have found her attention to stiffened with rhythmic shaking, be somewhat off over the last Sophia’s mouth was described common pediatric primary care physician with concerns of incontinence few weeks. Teachers have asked as “sort of twisted” and Sophia conditions. in sleep. Sophia is an parents if Sophia has been was drooling. The event lasted otherwise healthy child, with getting good rest as she has 90 seconds. Following, Sophia uncomplicated birth history, been falling asleep in class. was disoriented and very sleepy. Father reports his sister Dayton Children’s appropriate developmental Sophia’s mother and father had similar events as a child. progression with regards note that she has had is the region’s Sophia’s neurological exam to early milestones, and several episodes of urinary was normal, therefore her pediatric referral previously diurnal/nocturnally incontinence each week over pediatrician made a referral toilet trained. No report of the last 3-4 weeks. Parents center for a to pediatric neurology. Given recent illness, infection or ill have limited fluids prior to bed Sophia’s presentation, what 20-county area. -

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy What is Benign Rolandic Epilepsy (BRE)? Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is a common, mild form of childhood epilepsy characterized by brief simple partial seizures involving the face and mouth, usually occuring at night or during the early morning hours. Seizures are the result of brief disruptions in the brain’s normal neuronal activity. Who gets this form of epilepsy? Children between the ages of three and 13 years, who have no neurological or intellectual deficit.The peak age of onset is from 9-10 years of age. BRE is more common in boys than girls. What kind of seizures occur? Typically, the child experiences a sensation then a twitching at the corner of their mouth. The jerking spreads to in- volve the tongue, cheeks and face on one side, resulting in speech arrest, problems with pronunciation and drooling. Or one side of the child’s face may feel paralyzed. Consciousness is retained. On occasion, the seizure may spread and cause the arms and legs on that side to stiffen and or jerk, or it may become a generalized tonic-clonic seizure that involves the whole body and a loss of consciousness. When do the seizures occur? Seizures tend to happen when the child is waking up or during certain stages of sleep. Seizures may be infrequent, or can happen many times a day. How is Benign Rolandic Epilepsy diagnosed? A child having such seizures is given an EEG test to confirm the diagnosis, a test that graphs the pattern of electrical activity in the brain. BRE has a typical EEG spike pattern—repetitive spike activity firing predominantly from the mid-temporal or parietal areas of the brain near the rolandic (motor) strip. -

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment of Rolandic Epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos

ADC Online First, published on September 8, 2014 as 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304211 Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304211 on 8 September 2014. Downloaded from Review Antiepileptic drug treatment of rolandic epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos syndrome: clinical practice survey and clinical trial feasibility Louise C Mellish,1 Colin Dunkley,2 Colin D Ferrie,3 Deb K Pal1 ▸ Additional material is ABSTRACT published online only. To view Background The evidence base for management of What is already known on this topic? please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ childhood epilepsy is poor, especially for the most common specific syndromes such as rolandic epilepsy (RE) archdischild-2013-304211). ▸ UK management of rolandic epilepsy and and Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS). Considerable 1King’s College London, Panayiotopoulos syndrome are not well known international variation in management and controversy London, UK and there is limited scientific basis for drug 2 about non-treatment indicate the need for high quality Sherwood Forest Hospitals, treatment or non-treatment. Notts, UK randomised controlled trials (RCT). The aim of this study 3 ▸ Paediatric opinion towards clinical trial designs Department of Paediatric is, therefore, to describe current UK practice and explore is also unknown and important to assess prior Neurology, Leeds General the feasibility of different RCT designs for RE and PS. Infirmary, Leeds, UK to further planning. Methods We conducted an online survey of 590 UK Correspondence to paediatricians who treat epilepsy. Thirty-two questions Professor Deb K Pal, covered annual caseload, investigation and management Department of Basic and practice, factors influencing treatment, antiepileptic drug Clinical Neuroscience, King’s What this study adds? College London, Institute of preferences and hypothetical trial design preferences. -

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment of Rolandic Epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos

Review Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304211 on 8 September 2014. Downloaded from Antiepileptic drug treatment of rolandic epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos syndrome: clinical practice survey and clinical trial feasibility Louise C Mellish,1 Colin Dunkley,2 Colin D Ferrie,3 Deb K Pal1 ▸ Additional material is ABSTRACT published online only. To view Background The evidence base for management of What is already known on this topic? please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ childhood epilepsy is poor, especially for the most common specific syndromes such as rolandic epilepsy (RE) archdischild-2013-304211). ▸ UK management of rolandic epilepsy and and Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS). Considerable 1King’s College London, Panayiotopoulos syndrome are not well known international variation in management and controversy London, UK and there is limited scientific basis for drug 2 about non-treatment indicate the need for high quality Sherwood Forest Hospitals, treatment or non-treatment. Notts, UK randomised controlled trials (RCT). The aim of this study 3 ▸ Paediatric opinion towards clinical trial designs Department of Paediatric is, therefore, to describe current UK practice and explore is also unknown and important to assess prior Neurology, Leeds General the feasibility of different RCT designs for RE and PS. Infirmary, Leeds, UK to further planning. Methods We conducted an online survey of 590 UK Correspondence to paediatricians who treat epilepsy. Thirty-two questions Professor Deb K Pal, covered annual caseload, investigation and management Department of Basic and practice, factors influencing treatment, antiepileptic drug Clinical Neuroscience, King’s What this study adds? College London, Institute of preferences and hypothetical trial design preferences. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

Seizure, New Onset

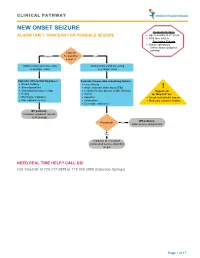

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

The Relationship Between the Components of Idiopathic Focal Epilepsy

Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care Review Article Open Access The relationship between the components of idiopathic focal epilepsy Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The classification of epileptic syndromes in children is not a simple duty, it requires Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon a great clinical ability as well as some degree of experience. Until today there is no Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of international consensus regarding the different diseases that are part of the Idiopathic Copenhagen, Denmark Focal Epilepsies However, these diseases are the most prevalent in children suffering from some type of epilepsy, for this reason it is important to know more about these, Correspondence: Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon their clinical characteristics, pathological findings in studies such as encephalogram, M.D., Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology Faculty resonance, polysomnography and others. In the same way, to explore the possible of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, genetic origins of many of these pathologies, that have been little explored and Denmark, Jagtev 160, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark, become an important therapeutic goal. A description of the most relevant aspects of Email [email protected] atypical benign partial epilepsy, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, electrical status epilepticus during sleep and Panayiotopoulos Received: February 17, 2018 | Published: May 14, 2018 syndrome is presented in this review, Allowing physicians and family members of children suffering from these diseases to have a better understanding and establish in this way a better diagnosis and treatment in patients, as well as promote in the scientific community the interest to investigate more about these relevant pathologies in childhood. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Analysis of Serial Electroencephalographic Predictors of Seizure Recurrence in Rolandic Epilepsy

Child's Nervous System (2019) 35:1579–1583 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04275-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Analysis of serial electroencephalographic predictors of seizure recurrence in Rolandic epilepsy Hongwei Tang1 & Yanping Wang1 & Ying Hua1 & Jianbiao Wang1 & Miao Jing1 & Xiaoyue Hu1 Received: 23 February 2019 /Accepted: 25 June 2019 /Published online: 2 July 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose We aimed to assess the relationship between electroencephalography (EEG) markers and seizure recurrence in cases with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECT) in a long-term follow-up study. Methods We analyzed the data of 52 children with BECT who were divided into 2 groups: the isolated group and recurrence group. The clinical profiles and initial/serial visual EEG recordings of both groups were evaluated. The entire follow-up period ranged from 12 to 65 months. Results None of the clinical characteristics differed between the 2 groups. Serial EEGs showed that the appearance of Rolandic spikes in the frontal region was more prevalent in the recurrence group. Moreover, a significant correlation was found between bilateral asynchronous discharges and seizure recurrence. However, on initial EEG of these patients, neither of the EEG features exhibited statistical significance. Conclusion The presence of frontal focus and bilateral asynchrony appeared to be hallmarks of BECT patients with higher risk for seizure recurrence. Keywords BECT . Rolandic epilepsy . EEG . Seizure Abbreviations Introduction EEG electroencephalography BECT Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, also MRI Magnetic resonance imaging known as benign Rolandic epilepsy, accounts for approxi- AEDs Antiepileptic drugs mately 13–25% of cases of epilepsy in school-aged children, LEV Levetiracetam and is one of the most common epileptic syndromes in child- OXC Oxcarbazepine hood [20]. -

Frontal Lobe Growth Retardation And

& The ics ra tr pe a u i t i d c e s Kanemura and Aihara, Pediat Therapeut 2013, 3:3 P Pediatrics & Therapeutics DOI: 10.4172/2161-0665.1000160 ISSN: 2161-0665 Research Article Open Access Frontal Lobe Growth Retardation and Dysfunctions in Children with Epilepsy: A 3-D MRI Volumetric Study Hideaki Kanemura1* and Masao Aihara2 1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Yamanashi, 1110 Chuo, Yamanashi 409-3898, Japan 2Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Medicine and Engineering, University of Yamanashi, Japan Abstract Behavioral abnormalities have been noted in specific epilepsy syndromes involving the frontal lobe. Epilepsies that involve the frontal lobe, such as frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE), atypical evolution of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTS), and epilepsy with continuous spike-waves during slow sleep (CSWS), are characterized by impairment of neuropsychological abilities, frequently associated with behavioral disorders. These manifestations correlate strongly with frontal lobe dysfunction. Accordingly, epilepsies in childhood may affect the prefrontal cortex and leave residual mental and behavioral abnormalities. Brain volumetry has shown that frontal and prefrontal lobe volumes show a growth disturbance in patients with FLE, atypical evolution of BCECTS, and CSWS compared with those of normal subjects. These studies also showed that seizures and the duration of paroxysmal anomalies may be associated with prefrontal lobe growth abnormalities, which are associated with neuropsychological problems. Moreover, these studies also showed that the prefrontal lobe appears more highly vulnerable to repeated seizures than other cortical regions. The urgent suppression of these seizure and EEG abnormalities may be necessary to prevent the progression of neuropsychological impairments. -

A Prospective Open-Labeled Trial with Levetiracetam in Pediatric Epilepsy Syndromes: Continuous Spikes and Waves During Sleep Is Definitely a Target

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Seizure 20 (2011) 320–325 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seizure journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yseiz A prospective open-labeled trial with levetiracetam in pediatric epilepsy syndromes: Continuous spikes and waves during sleep is definitely a target S. Chhun a,b,c, P. Troude d, N. Villeneuve e, C. Soufflet a,b,f, S. Napuri g, J. Motte h, F. Pouplard i, C. Alberti d, S. Helfen j, G. Pons a,b,c, O. Dulac a,b,k, C. Chiron a,b,k,* a Inserm, U663, Paris, France b University Paris Descartes, Faculty of Medicine, Paris, France c APHP, Pediatric Clinical Pharmacology, Cochin-Saint Vincent de Paul Hospital, Paris, France d APHP, Unit of Clinical Research, Robert Debre Hospital, Paris, France e APHM, Neuropediatric Department, Marseille, France f APHP, Necker Hospital, Department of Functional Explorations, Paris, France g Neuropediatric Department, Rennes Hospital, France h Neuropediatric Department, American Memorial Hospital, Reims, France i Neuropediatric Department, Angers Hospital, France j APHP, Necker Hospital, Unit of Clinical Research, Paris, France k APHP, Necker Hospital, Neuropediatric Department, Paris, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Although LVT is currently extensively prescribed in childhood epilepsy, its effect on the panel of Received 12 October 2010 refractory epilepsy syndromes has not been entirely evaluated prospectively. In order to study the Received in revised form 17 December 2010 efficacy and safety of LVT as adjunctive therapy according to syndromes, we included 102 patients with Accepted 27 December 2010 refractory seizures (6 months to 15 years) in a prospective open-labeled trial. -

Prospective Evaluation of Interrater Agreement Between EEG Technologists and Neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prospective evaluation of interrater agreement between EEG technologists and neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S. Reif1,2,3, Nora Sterlepper1,2, Felix Rosenow1,2 & Adam Strzelczyk 1,2* We aim to prospectively investigate, in a large and heterogeneous population, the electroencephalogram (EEG)-reading performances of EEG technologists. A total of 8 EEG technologists and 5 certifed neurophysiologists independently analyzed 20-min EEG recordings. Interrater agreement (IRA) for predefned EEG pattern identifcation between EEG technologists and neurophysiologits was assessed using percentage of agreement (PA) and Gwet-AC1. Among 1528 EEG recordings, the PA [95% confdence interval] and interrater agreement (IRA, AC1) values were as follows: status epilepticus (SE) and seizures, 97% [96–98%], AC1 kappa = 0.97; interictal epileptiform discharges, 78% [76–80%], AC1 = 0.63; and conclusion dichotomized as “normal” versus “pathological”, 83.6% [82–86%], AC1 = 0.71. EEG technologists identifed SE and seizures with 99% [98–99%] negative predictive value, whereas the positive predictive values (PPVs) were 48% [34– 62%] and 35% [20–53%], respectively. The PPV for normal EEGs was 72% [68–76%]. SE and seizure detection were impaired in poorly cooperating patients (SE and seizures; p < 0.001), intubated and older patients (SE; p < 0.001), and confrmed epilepsy patients (seizures; p = 0.004). EEG technologists identifed ictal features with few false negatives but high false positives, and identifed normal EEGs with good PPV. The absence of ictal features reported by EEG technologists can be reassuring; however, EEG traces should be reviewed by neurophysiologists before taking action.