EEG Findings in Pediatric Epilepsy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myths and Truths About Pediatric Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures

Clin Exp Pediatr Vol. 64, No. 6, 251–259, 2021 Review article CEP https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2020.00892 Myths and truths about pediatric psychogenic nonepileptic seizures Jung Sook Yeom, MD, PhD1,2,3, Heather Bernard, LCSW4, Sookyong Koh, MD, PhD3,4 1Department of Pediatrics, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, 2Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University College of Medicine, Jinju, Korea; 3Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA; 4Department of Pediatrics, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA, USA Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) is a neuropsychiatric • PNES are a manifestation of psychological and emotional condition that causes a transient alteration of consciousness and distress. loss of self-control. PNES, which occur in vulnerable individuals • Treatment for PNES does not begin with the psychological who often have experienced trauma and are precipitated intervention but starts with the diagnosis and how the dia- gnosis is delivered. by overwhelming circumstances, are a body’s expression of • A multifactorial biopsychosocial process and a neurobiological a distressed mind, a cry for help. PNES are misunderstood, review are both essential components when treating PNES mistreated, under-recognized, and underdiagnosed. The mind- body dichotomy, an artificial divide between physical and mental health and brain disorders into neurology and psychi- atry, contributes to undue delays in the diagnosis and treat ment Introduction of PNES. One of the major barriers in the effective dia gnosis and treatment of PNES is the dissonance caused by different illness Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are paroxysmal perceptions between patients and providers. While patients attacks that may resemble epileptic seizures but are not caused are bewildered by their experiences of disabling attacks beyond by abnormal brain electrical discharges. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

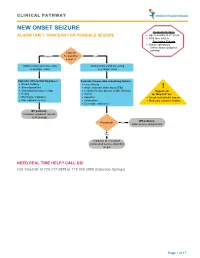

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

The Relationship Between the Components of Idiopathic Focal Epilepsy

Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care Review Article Open Access The relationship between the components of idiopathic focal epilepsy Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The classification of epileptic syndromes in children is not a simple duty, it requires Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon a great clinical ability as well as some degree of experience. Until today there is no Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of international consensus regarding the different diseases that are part of the Idiopathic Copenhagen, Denmark Focal Epilepsies However, these diseases are the most prevalent in children suffering from some type of epilepsy, for this reason it is important to know more about these, Correspondence: Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon their clinical characteristics, pathological findings in studies such as encephalogram, M.D., Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology Faculty resonance, polysomnography and others. In the same way, to explore the possible of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, genetic origins of many of these pathologies, that have been little explored and Denmark, Jagtev 160, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark, become an important therapeutic goal. A description of the most relevant aspects of Email [email protected] atypical benign partial epilepsy, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, electrical status epilepticus during sleep and Panayiotopoulos Received: February 17, 2018 | Published: May 14, 2018 syndrome is presented in this review, Allowing physicians and family members of children suffering from these diseases to have a better understanding and establish in this way a better diagnosis and treatment in patients, as well as promote in the scientific community the interest to investigate more about these relevant pathologies in childhood. -

Semiological Bridge Between Psychiatry and Epilepsy

Journal of Psychology and Clinical Psychiatry Semiological Bridge between Psychiatry and Epilepsy Abstract Review Article Epilepsy is a paroxysmal disturbance of brain function that presents as behavioral phenomena involving four spheres; sensory, motor, autonomic and consciousness. These behavioural disturbances though transient but may be Volume 8 Issue 1 - 2017 confused with psychiatric disorders. Thus representing a diagnostic problem Department of Neuropsychiatry, Ain Shams University, Egypt for neurophyschiatrists. Here we review the grey zone between psychiatry and epilepsy on three levels. The first level is the semiology itself, that the behavioral *Corresponding author: Ahmed Gaber, Prof. of phenomenon at a time can be the presentation of an epileptic disorder and at Neuropsychiatry, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, another time a representation of a psychiatric disorder. The second level is Email: the comorbidity between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders namely epileptic psychosis. The third level is the disorders of the brain that can present by both Received: | Published: epileptic and/or psychiatric disorders. We reviewed the current literature in both June 11, 2017 July 12, 2017 epilepsy and Psychiatry including the main presentations that might be confusing. Conclusion: Epilepsy, schizophrenia like psychosis, intellectual disability, autism are different disorders that may share same semiological presentation, comorbidity or even etiology. A stepwise mental approach and decision making is needed excluding seizure disorder first before diagnosing a psychiatric one. Keywords: Epilepsy, Psychosis; Schizophrenia; Semiology; Autoimmune encephalitis Discussion with consciousness are called dialeptic seizures. Seizures Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by an enduring consistingseizures are primarily identified of as autonomic auras. Seizures symptoms that interfere are called primarily either predisposition of recurrent seizures. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Frequently Asked Questions

EPILEPSY AND SEIZURES – GENERAL Frequently Asked Questions What is epilepsy? Seizures are divided into two main categories: Epilepsy is a common neurological disease Generalized seizures characterized by the tendency to have recurrent • Involve both hemispheres of the brain seizures. It is sometimes called a seizure disorder. • Two common types are absence seizures (petit A person has epilepsy if they: mal seizures) and tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal seizures) • Have had at least two unprovoked seizures, or • Have had one seizure and are very likely to Focal seizures (partial seizures) have another, or • Only involve one part of the brain • Are diagnosed with an epilepsy syndrome • Include focal impaired awareness seizures (complex partial seizures) and focal aware seizures (simple partial seizures). What is a seizure? People with epilepsy may experience more than one A seizure is a sudden burst of electrical activity in the type of seizure. For more information about seizure brain that causes a temporary disturbance in the way types, see our Seizure Types Spark sheet. brain cells communicate with each other. The kind of seizure a person has depends on which part and how much of the brain is affected by the electrical FACT: About 1 in 100 Canadians have epilepsy. disturbance that produces the seizure. A seizure may take many different forms, including a blank stare, Why do people have seizures? uncontrolled movements, altered awareness, odd sensations, or convulsions. Seizures are typically brief There are many potential reasons why someone could and can last anywhere from a few seconds to a few have a seizure. Some seizures are a symptom of an minutes. -

Comprehensive Epilepsy Center the Only Level 4 Designated Center in Metropolitan Washington, D.C

Comprehensive Epilepsy Center The Only Level 4 Designated Center in Metropolitan Washington, D.C. 3 Seizing Control On the Road Again Daniele Wishnow endured eight Epilepsy affects nearly 3 million people years of medications and side- in the United States or about one out of every 100 Americans. Many effects, a major car accident and losing the ability to drive before spend years—often their entire lives—taking various medications for she finally discovered the epilepsy experts at MedStar Georgetown their disorder, usually with good results. But uncontrolled, epilepsy University Hospital. Months later, can limit an individual’s ability to drive, work or enjoy other activities. her life was back on track. “At my worst, I had a combination of grand mal seizures—losing However, there is hope. consciousness, collapsing and Neurosurgeon Chris Kalhorn, MD, jerking,” Daniele says, “along with performs delicate and intricate surgery multiple small seizures that made to control seizures. When traditional approaches fail, MedStar Georgetown University me blank out for a few seconds or so. For a long time, medications So on January 2013, Christopher Hospital can help. Our Comprehensive Epilepsy Center features kept them pretty much under Kalhorn, MD—director of experts who can accurately locate the precise area of the brain control, but then they quit functional, pediatric and epilepsy working.” neurosurgery—successfully causing seizures in both adults and children. And with the right removed Daniele’s lesion. Today, Daniele underwent evaluation at Daniele’s back on the road and diagnosis, we can tailor personalized treatment plans to reduce or MedStar Georgetown’s Level 4 back to living a full life. -

Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures: Diagnostic Challenges and Treatment Dilemmas Taoufik Alsaadi1* and Tarek M Shahrour2

Alsaadi and Shahrour. Int J Neurol Neurother 2015, 2:1 International Journal of DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/2/1/1020 Volume 2 | Issue 1 Neurology and Neurotherapy ISSN: 2378-3001 Review Article: Open Access Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures: Diagnostic Challenges and Treatment Dilemmas Taoufik Alsaadi1* and Tarek M Shahrour2 1Department of Neurology, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, UAE 2Department of Psychiatry, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, UAE *Corresponding author: Taoufik Alsaadi, Department of Neurology, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, UAE, E-mail: [email protected] They are thought to be a form of physical manifestation of psychological Abstract distress. Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures (PNES) are grouped in Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures (PNES) are episodes of the category of psycho-neurologic illnesses like other conversion and movement, sensation or behavior changes similar to epileptic somatization disorders, in which symptoms are psychological in origin seizures but without neurological origin. They are somatic but neurologic in expression [4]. The purpose of this review is to shed manifestations of psychological distress. Patients with PNES are often misdiagnosed and treated for epilepsy for years, resulting in light on this common, but, often times, misdiagnosed problem. It has significant morbidity. Video-EEG monitoring is the gold standard for been estimated that approximately 20 to 30% of patients referred to diagnosis. Five to ten percent of outpatient epilepsy populations and epilepsy centers have PNES [5]. Still, it takes an average of 7 years before 20 to 40 percent of inpatient and specialty epilepsy center patients accurate diagnosis and appropriate referral is made [6]. Early recognition have PNES. These patients inevitably have comorbid psychiatric and appropriate treatment can prevent significant iatrogenic harm, and illnesses, most commonly depression, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), other dissociative and somatoform disorders, may result in a better outcome. -

A Prospective Open-Labeled Trial with Levetiracetam in Pediatric Epilepsy Syndromes: Continuous Spikes and Waves During Sleep Is Definitely a Target

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Seizure 20 (2011) 320–325 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seizure journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yseiz A prospective open-labeled trial with levetiracetam in pediatric epilepsy syndromes: Continuous spikes and waves during sleep is definitely a target S. Chhun a,b,c, P. Troude d, N. Villeneuve e, C. Soufflet a,b,f, S. Napuri g, J. Motte h, F. Pouplard i, C. Alberti d, S. Helfen j, G. Pons a,b,c, O. Dulac a,b,k, C. Chiron a,b,k,* a Inserm, U663, Paris, France b University Paris Descartes, Faculty of Medicine, Paris, France c APHP, Pediatric Clinical Pharmacology, Cochin-Saint Vincent de Paul Hospital, Paris, France d APHP, Unit of Clinical Research, Robert Debre Hospital, Paris, France e APHM, Neuropediatric Department, Marseille, France f APHP, Necker Hospital, Department of Functional Explorations, Paris, France g Neuropediatric Department, Rennes Hospital, France h Neuropediatric Department, American Memorial Hospital, Reims, France i Neuropediatric Department, Angers Hospital, France j APHP, Necker Hospital, Unit of Clinical Research, Paris, France k APHP, Necker Hospital, Neuropediatric Department, Paris, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Although LVT is currently extensively prescribed in childhood epilepsy, its effect on the panel of Received 12 October 2010 refractory epilepsy syndromes has not been entirely evaluated prospectively. In order to study the Received in revised form 17 December 2010 efficacy and safety of LVT as adjunctive therapy according to syndromes, we included 102 patients with Accepted 27 December 2010 refractory seizures (6 months to 15 years) in a prospective open-labeled trial. -

How to Identify Migraine with Aura Kathleen B

How to Identify Migraine with Aura Kathleen B. Digre MD, FAHS Migraine is very common—affecting 20% of women and (continuous dots that are present all of the time but do not almost 8% of men. Migraine with aura occurs in about obscure vision and appear like a faulty analog television set), one-third of those with migraine. Visual symptoms such as (Schankin et al), visual blurring and short visual phenomena photophobia, blurred vision, sparkles and flickering are all (Friedman). Migraine visual auras are usually stereotypic for reported in individuals with migraine. But how do you know if an individual. what a patient is experiencing is aura? Figure: Typical aura drawn by a primary care resident: The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD 3) suggests that auras may be visual (most common—90% of all auras), sensory, speech and or language, motor, brainstem or retinal. The typical aura starts out gradually over 5 minutes and lasts 5-60 minutes, is usually unilateral and may be followed by a headache within 60 minutes. To identify aura, we rely on the patient’s description of the phenomena. One helpful question to ask patients to determine if they are experiencing visual aura is: Was this in one eye or both eyes? Many patients will report it in ONE eye but if they haven’t covered each eye when they have the phenomena and try to read text, they may be misled. If you can have them draw their aura (typical zig-zag lines) with scintillations (movement, like a kaleidoscope) across their vision, you know it is an aura. -

Prospective Evaluation of Interrater Agreement Between EEG Technologists and Neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prospective evaluation of interrater agreement between EEG technologists and neurophysiologists Isabelle Beuchat 1,2, Senubia Alloussi1,2, Philipp S. Reif1,2,3, Nora Sterlepper1,2, Felix Rosenow1,2 & Adam Strzelczyk 1,2* We aim to prospectively investigate, in a large and heterogeneous population, the electroencephalogram (EEG)-reading performances of EEG technologists. A total of 8 EEG technologists and 5 certifed neurophysiologists independently analyzed 20-min EEG recordings. Interrater agreement (IRA) for predefned EEG pattern identifcation between EEG technologists and neurophysiologits was assessed using percentage of agreement (PA) and Gwet-AC1. Among 1528 EEG recordings, the PA [95% confdence interval] and interrater agreement (IRA, AC1) values were as follows: status epilepticus (SE) and seizures, 97% [96–98%], AC1 kappa = 0.97; interictal epileptiform discharges, 78% [76–80%], AC1 = 0.63; and conclusion dichotomized as “normal” versus “pathological”, 83.6% [82–86%], AC1 = 0.71. EEG technologists identifed SE and seizures with 99% [98–99%] negative predictive value, whereas the positive predictive values (PPVs) were 48% [34– 62%] and 35% [20–53%], respectively. The PPV for normal EEGs was 72% [68–76%]. SE and seizure detection were impaired in poorly cooperating patients (SE and seizures; p < 0.001), intubated and older patients (SE; p < 0.001), and confrmed epilepsy patients (seizures; p = 0.004). EEG technologists identifed ictal features with few false negatives but high false positives, and identifed normal EEGs with good PPV. The absence of ictal features reported by EEG technologists can be reassuring; however, EEG traces should be reviewed by neurophysiologists before taking action.