Benign Childhood Seizure Susceptibility Syndromes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment

NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. NEUROLOGY – LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS SERIES Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-862-7 (Hardcover Book) Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60876-549-2 (Online Book) Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation Nodar P. Mitagvaria and Haim (James) I. Bicher 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60692-163-0 Cerebral Ischemia in Young Adults: Pathogenic and Clinical Perspectives Alessandro Pezzini and Alessandro Padovani (Editors) 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-627-2 Dizziness: Vertigo, Disequilibrium and Lightheadedness Agnes Lindqvist and Gjord Nyman (Editors) 2009: ISBN 978-1-60741-847-4 Somatosensory Cortex: Roles, Interventions and Traumas Niels Johnsen and Rolf Agerskov (Editors) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60741-876-4 Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment Melanie L. Landow (Editor) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60876-205-7 NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MELANIE L. -

Pediatric Epilepsy Clips by Pediatric Elizabeth Medaugh, MSN, CPNP-PC , Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Neurology

Nursing May 2016 Pediatric Clips Pediatric Nursing Pediatric Epilepsy Clips by Pediatric Elizabeth Medaugh, MSN, CPNP-PC , Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Neurology Advanced Practice Sophia had been exceeding down to sleep, mother heard a Nurses at Dayton Case Study the expectations of school. thump and went to check on her. Her teachers report her being Sophia’s eyes were wide open Children’s provides Sophia is a 7 year old Caucasian focused the first two quarters, and deviated left, left arm was quick reviews of female who presented to her but have found her attention to stiffened with rhythmic shaking, be somewhat off over the last Sophia’s mouth was described common pediatric primary care physician with concerns of incontinence few weeks. Teachers have asked as “sort of twisted” and Sophia conditions. in sleep. Sophia is an parents if Sophia has been was drooling. The event lasted otherwise healthy child, with getting good rest as she has 90 seconds. Following, Sophia uncomplicated birth history, been falling asleep in class. was disoriented and very sleepy. Father reports his sister Dayton Children’s appropriate developmental Sophia’s mother and father had similar events as a child. progression with regards note that she has had is the region’s Sophia’s neurological exam to early milestones, and several episodes of urinary was normal, therefore her pediatric referral previously diurnal/nocturnally incontinence each week over pediatrician made a referral toilet trained. No report of the last 3-4 weeks. Parents center for a to pediatric neurology. Given recent illness, infection or ill have limited fluids prior to bed Sophia’s presentation, what 20-county area. -

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy What is Benign Rolandic Epilepsy (BRE)? Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is a common, mild form of childhood epilepsy characterized by brief simple partial seizures involving the face and mouth, usually occuring at night or during the early morning hours. Seizures are the result of brief disruptions in the brain’s normal neuronal activity. Who gets this form of epilepsy? Children between the ages of three and 13 years, who have no neurological or intellectual deficit.The peak age of onset is from 9-10 years of age. BRE is more common in boys than girls. What kind of seizures occur? Typically, the child experiences a sensation then a twitching at the corner of their mouth. The jerking spreads to in- volve the tongue, cheeks and face on one side, resulting in speech arrest, problems with pronunciation and drooling. Or one side of the child’s face may feel paralyzed. Consciousness is retained. On occasion, the seizure may spread and cause the arms and legs on that side to stiffen and or jerk, or it may become a generalized tonic-clonic seizure that involves the whole body and a loss of consciousness. When do the seizures occur? Seizures tend to happen when the child is waking up or during certain stages of sleep. Seizures may be infrequent, or can happen many times a day. How is Benign Rolandic Epilepsy diagnosed? A child having such seizures is given an EEG test to confirm the diagnosis, a test that graphs the pattern of electrical activity in the brain. BRE has a typical EEG spike pattern—repetitive spike activity firing predominantly from the mid-temporal or parietal areas of the brain near the rolandic (motor) strip. -

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment of Rolandic Epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos

ADC Online First, published on September 8, 2014 as 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304211 Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304211 on 8 September 2014. Downloaded from Review Antiepileptic drug treatment of rolandic epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos syndrome: clinical practice survey and clinical trial feasibility Louise C Mellish,1 Colin Dunkley,2 Colin D Ferrie,3 Deb K Pal1 ▸ Additional material is ABSTRACT published online only. To view Background The evidence base for management of What is already known on this topic? please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ childhood epilepsy is poor, especially for the most common specific syndromes such as rolandic epilepsy (RE) archdischild-2013-304211). ▸ UK management of rolandic epilepsy and and Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS). Considerable 1King’s College London, Panayiotopoulos syndrome are not well known international variation in management and controversy London, UK and there is limited scientific basis for drug 2 about non-treatment indicate the need for high quality Sherwood Forest Hospitals, treatment or non-treatment. Notts, UK randomised controlled trials (RCT). The aim of this study 3 ▸ Paediatric opinion towards clinical trial designs Department of Paediatric is, therefore, to describe current UK practice and explore is also unknown and important to assess prior Neurology, Leeds General the feasibility of different RCT designs for RE and PS. Infirmary, Leeds, UK to further planning. Methods We conducted an online survey of 590 UK Correspondence to paediatricians who treat epilepsy. Thirty-two questions Professor Deb K Pal, covered annual caseload, investigation and management Department of Basic and practice, factors influencing treatment, antiepileptic drug Clinical Neuroscience, King’s What this study adds? College London, Institute of preferences and hypothetical trial design preferences. -

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment of Rolandic Epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos

Review Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304211 on 8 September 2014. Downloaded from Antiepileptic drug treatment of rolandic epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos syndrome: clinical practice survey and clinical trial feasibility Louise C Mellish,1 Colin Dunkley,2 Colin D Ferrie,3 Deb K Pal1 ▸ Additional material is ABSTRACT published online only. To view Background The evidence base for management of What is already known on this topic? please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ childhood epilepsy is poor, especially for the most common specific syndromes such as rolandic epilepsy (RE) archdischild-2013-304211). ▸ UK management of rolandic epilepsy and and Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS). Considerable 1King’s College London, Panayiotopoulos syndrome are not well known international variation in management and controversy London, UK and there is limited scientific basis for drug 2 about non-treatment indicate the need for high quality Sherwood Forest Hospitals, treatment or non-treatment. Notts, UK randomised controlled trials (RCT). The aim of this study 3 ▸ Paediatric opinion towards clinical trial designs Department of Paediatric is, therefore, to describe current UK practice and explore is also unknown and important to assess prior Neurology, Leeds General the feasibility of different RCT designs for RE and PS. Infirmary, Leeds, UK to further planning. Methods We conducted an online survey of 590 UK Correspondence to paediatricians who treat epilepsy. Thirty-two questions Professor Deb K Pal, covered annual caseload, investigation and management Department of Basic and practice, factors influencing treatment, antiepileptic drug Clinical Neuroscience, King’s What this study adds? College London, Institute of preferences and hypothetical trial design preferences. -

A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy And

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Neurological Medicine Volume 2013, Article ID 460701, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/460701 Case Report A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and Multicentric Castleman’s Disease Mohankumar Kurukumbi,1 Sheldon Steiner,1,2 Shariff Dunlap,1 Sherita Chapman,3 Noha Solieman,1 and Annapurni Jayam-Trouth1 1 Department of Neurology, Howard University Hospital, 2041 Georgia Avenue, Washington, DC 20060, USA 2 Department of Neurology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC 20060, USA 3 Department of Neurology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Mohankumar Kurukumbi; [email protected] Received 27 June 2013; Accepted 17 July 2013 AcademicEditors:T.K.Banerjee,J.L.Gonzalez-Guti´ errez,´ R. Hashimoto, J. C. Kattah, and Y. Wakabayashi Copyright © 2013 Mohankumar Kurukumbi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) development in HIV with preexistent progressive multifocal leukoen- cephalopathy (PML) has been extensively studied. PML-IRIS typically manifests clinically as new or worsening neurologic symptoms in conjunction with enlarging CNS lesions and occurs in approximately 10–20 percent of HIV-infected patients with PML who begin HAART. Likewise, Multicentric Castleman’s Disease (MCD), a rare malignant lymphoproliferative disorder, has a strong and well-known association with HIV. Our case provides a rare instance of PML-IRIS in combination with MCD in an HIV-positive individual. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

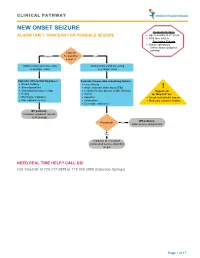

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

The Relationship Between the Components of Idiopathic Focal Epilepsy

Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care Review Article Open Access The relationship between the components of idiopathic focal epilepsy Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The classification of epileptic syndromes in children is not a simple duty, it requires Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon a great clinical ability as well as some degree of experience. Until today there is no Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of international consensus regarding the different diseases that are part of the Idiopathic Copenhagen, Denmark Focal Epilepsies However, these diseases are the most prevalent in children suffering from some type of epilepsy, for this reason it is important to know more about these, Correspondence: Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon their clinical characteristics, pathological findings in studies such as encephalogram, M.D., Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology Faculty resonance, polysomnography and others. In the same way, to explore the possible of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, genetic origins of many of these pathologies, that have been little explored and Denmark, Jagtev 160, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark, become an important therapeutic goal. A description of the most relevant aspects of Email [email protected] atypical benign partial epilepsy, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, electrical status epilepticus during sleep and Panayiotopoulos Received: February 17, 2018 | Published: May 14, 2018 syndrome is presented in this review, Allowing physicians and family members of children suffering from these diseases to have a better understanding and establish in this way a better diagnosis and treatment in patients, as well as promote in the scientific community the interest to investigate more about these relevant pathologies in childhood. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy.