A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment

NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. NEUROLOGY – LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS SERIES Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-862-7 (Hardcover Book) Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60876-549-2 (Online Book) Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation Nodar P. Mitagvaria and Haim (James) I. Bicher 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60692-163-0 Cerebral Ischemia in Young Adults: Pathogenic and Clinical Perspectives Alessandro Pezzini and Alessandro Padovani (Editors) 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-627-2 Dizziness: Vertigo, Disequilibrium and Lightheadedness Agnes Lindqvist and Gjord Nyman (Editors) 2009: ISBN 978-1-60741-847-4 Somatosensory Cortex: Roles, Interventions and Traumas Niels Johnsen and Rolf Agerskov (Editors) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60741-876-4 Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment Melanie L. Landow (Editor) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60876-205-7 NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MELANIE L. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

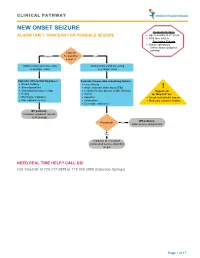

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

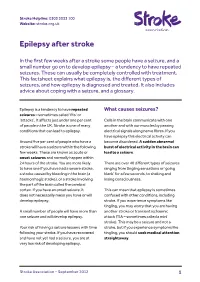

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

Supplementary Table Term* Revised Term** Focal Seizure Without Impairment of a Subjective Sensory Or Psychic Experience As Part of Migraine Or Epilepsy

Supplementary table Term* Revised term** Focal seizure without impairment of A subjective sensory or psychic experience as part of migraine or epilepsy. In epilepsy it is a focal consciousness or awareness Aura seizure without loss of consciousness (a simple partial seizure). It may or may not be followed by involving subjective sensory or other seizure manifestations. psychic phenomena only Automatic behaviour associated with loss of awareness, such as lip smacking or hand wringing, Automatism Focal dyscognitive seizure occurring as part of a complex partial seizure. Convulsion (previously "grand Tonic-clonic seziure, convulsive Seizure with involuntary, irregular myoclonic, clonic or tonic–clonic movements of one or more mal") seizure limbs. Onset may be focal or primary generalised. Literally ‘already seen’, this refers to a false impression that a present experience is familiar. It is used to refer to something heard, experienced or seen. It can be the aura of a temporal lobe Déjà vu seizure, but also happens in other settings (normal experience, intoxication, migraine, psychiatric). Focal seizure (previously "partial, Focal seizure A seizure originating in a specific cortical location. May be due to a structural lesion. localization related") Literally a ‘blow’. Usually used for an epileptic seizure (but can refer to other paroxysmal events, Ictus such as migraine, transient neurological events and stroke). Similarly pre- and post-ictal are used may for the period before and after a seizure. Idiopathic Genetic In relation to epilepsy, this implies that there is an underlying genetic cause. Literally ‘never seen’, this refers to a false impression that a present experience is unfamiliar. It is Jamais vu used for something seen, heard or experienced. -

Multimodal Longitudinal Imaging of Focal Status Epilepticus

CASE REPORT Multimodal Longitudinal Imaging of Focal Status Epilepticus Colin P. Doherty, Andrew J. Cole, P. Ellen Grant, Alan Fischman, Elizabeth Dooling, Daniel B. Hoch, Tessa Hedley White, G. Rees Cosgrove ABSTRACT: Background: Little is understood about the evolution of structural and functional brain changes during the course of uncontrolled focal status epilepticus in humans. Methods: We serially evaluated and treated a nine-year-old girl with refractory focal status epilepticus. Long-term EEG monitoring, MRI, MRA, SPECT, intraoperative visualization of affected cortex, and neuropathological examination of a biopsy specimen were conducted over a three year time span. Imaging changes were correlated with simultaneous treatment and EEG findings. Results: The EEG monitoring showed almost continuous spike discharges emanating initially from the right frontocentral area. These EEG abnormalities were intermittently suppressed by treatment with anesthetics. Over time, additional brain areas developed epileptiform EEG abnormalities. Serial MRI studies demonstrated an evolution of changes from normal, through increased regional T2 signal to generalized atrophy. An MRAdemonstrated dilatation of the middle cerebral artery stem on the right compared to the left with a broad distribution of flow-related enhancement. An 18FDG-PET scan showed a dramatically abnormal metabolic profile in the same right frontocentral areas, which modulated in response to treatment during the course of the illness. A right frontotemporal craniotomy revealed a markedly hyperemic cortical focus including vascular shunting. A sample of resected cortex showed severe gliosis and neuronal death. Conclusions: The co-registration of structural and functional imaging and its correlation with operative and pathological findings in this case illustrates the relentless progression of regional and generalized abnormalities in intractable focal status epilepticus that were only transiently modified by exhaustive therapeutic interventions. -

“Top Neurology Cases” Ohsui.E

“Top Neurology Cases” OHSUi.e. Headache, etc. Doernbecher Annual Review DATE: October 3, 2019 BY: Kaitlin Greene, MD Director, Pediatric Headache OHSU Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Neurology Disclosures OHSU• None Outline: • Case 1: Headache • Case 2: Seizure • Case 3: Stroke OHSU• Discussion and Questions! 33 Case 1: Headache • Goals: • Review indications for imaging in patient presenting with headache • Review diagnostic criteria for migraine and migraine with aura in children and adolescents • Outline approach to acute and preventive treatment of headaches OHSU• Be comfortable prescribing a triptan! Case 1: Headache • 13 year old girl presenting with worsening headaches • When did headaches start? • Six months ago Age 8 • Short (~1 hour), infrequent (<1x/month), typically triggered by illness or dehydration, improved with ibuprofen • Over the past two years, frequency gradually increased to OHSU2x/month, then 4x/month, then to 2x/week by about 6 months ago Case 1: Headache • What are the headaches like? • Location: Mostly front, sometime back, sometimes more on one side or the other • Quality: Pressure (throbbing when severe) • Severity: Usually moderate, at least 2/month severe • What are the associated features • “Sensory sensitivity”: Light, sound, smell OHSU• Nausea when severe • Sees “flashes of light” for a few seconds with more severe headaches Itsoktobeweird.com Case 1: Headache • PMH: None • Family history: • Mom with “stress headaches” (Gets sensitive to light/noise, has to lie down) • Younger sister gets headaches when sick • Medications: • Ibuprofen 200 mg as needed for headache • Exam: Wt 50 kg. Normal including fundoscopic OHSUexam. Case 1: Headache - Diagnosis • What is the diagnosis? Migraine! With Aura? • BUT first have to answer two questions: 1. -

Epilepsy & My Child Toolkit

Epilepsy & My Child Toolkit A Resource for Parents with a Newly Diagnosed Child 136EMC Epilepsy & My Child Toolkit A Resource for Parents with a Newly Diagnosed Child “Obstacles are the things we see when we take our eyes off our goals.” -Zig Ziglar EPILEPSY & MY CHILD TOOLKIT • TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Purpose .............................................................................................................................................5 How to Use This Toolkit ....................................................................................................................5 About Epilepsy What is Epilepsy? ..............................................................................................................................7 What is a Seizure? .............................................................................................................................8 Myths & Facts ...................................................................................................................................8 How is Epilepsy Diagnosed? ............................................................................................................9 How is Epilepsy Treated? ..................................................................................................................10 Managing Epilepsy How Can You Help Manage Your Child’s Care? ...............................................................................13 What Should You Do if Your Child has a Seizure? ............................................................................14 -

The Comorbidity of Headaches in Pediatric Epilepsy Patients: How Common and What Types?

The comorbidity of headaches in pediatric epilepsy patients: How common and what types? Hanin Al-Gethami, MD, Muhammad Talal Alrifai, MD, Ahmed AlRumayyan, MD, Waleed AlTuwaijri, MD, Duaa Baarmah, MD. ABSTRACT of Saudi Arabia using a structured questionnaire in pediatric patients with epilepsy. اﻷهداف: كان هدفنا هو تقدير مدى انتشارالصداع وخصائصه Results: ,There were 142 patients enrolled )males لدى مرضى الصرع عند اﻷطفال. 57.7%; average age, 10.7±3.1 years( with idiopathic epilepsy )n=115, 81%( or symptomatic epilepsy n=27, 19%(. Additionally, patients had focal epilepsy( املنهجية: أجريت هذه الدراسة على مدى 6 أشهر من يناير 2018م ,)n=102, 72%( or generalized epilepsy )n=40, 28%( إلى يونيو 2018م في مستشفى امللك عبد اهلل التخصصي لﻷطفال، and among them, 11 had absence epilepsy. Overall, 65 مدينة امللك عبد العزيز الطبية، الرياض، باستخدام استبيان منظم. )45.7%( patients had headaches compared with 3/153 in the control group )p<0.0001(. Among the 65 )%2( كان هناك 142 مريضا مسجلني )ذكور، %57.7 ؛ -patients with headaches, 29 )44.6%( had migraine النتائج: 10.7±3.1 )type, 12 )18.4%( had tension-type, and 24 )36.9% متوسط العمر ، سنة( يعانون من الصرع مجهول السبب n=115, 81%( had unclassified headache. There was no significant( أو الصرع العرضي )n=27, 19%(. باﻹضافة إلى ,difference in age, gender, type of epilepsy syndrome مرضى الصرع البؤري )n=102, 72%( أو الصرع املعمم ),n=40 and antiepileptic used except in patients with or %28(، ومن بينهم، كان هناك 11 مريض مصاب بنوبات الغيبوبة. without headache. For migraine patients, there was كان 65 )%45.7( من املرضى يعانون من الصداع مقارنة مع 3/153 a lower headache prevalence in the subgroup treated )%2( في مجموعة الشاهد )p<0.0001( و من بني 65 ًمريضا، with valproic acid compared with other treatments. -

Seizure Ending Signs in Patients with Dyscognitive Focal Seizures*

Journal Identification = EPD Article Identification = 0763 Date: September 4, 2015 Time: 2:38 pm Original article with video sequences Epileptic Disord 2015; 17 (3): 255-62 Seizure ending signs in patients with dyscognitive focal seizures* Jay R. Gavvala, Elizabeth E. Gerard, Mícheál Macken, Stephan U. Schuele Department of Neurology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA Received October 11, 2014; Accepted July 04, 2015 ABSTRACT – Aim. Signs indicating the end of a focal seizure with loss of awareness and/or responsiveness but without progression to focal or gener- alized motor symptoms are poorly defined and can be difficult to determine. Not recognizing the transition from ictal to postictal behaviour can affect seizure reporting accuracy by family members and may lead to delayed or a lack of examination during EEG monitoring, erroneous seizure localiza- tion and inadequate medical intervention for prolonged seizure duration. Methods. Our epilepsy monitoring unit database was searched for focal seizures without secondary generalization for the period from 2007 to 2011. The first focal seizure in a patient with loss of awareness and/or responsive- ness and/or behavioural arrest, with or without automatisms, was included. Seizures without objective symptoms or inadequate video-EEG quality were excluded. Results. A total of 67 patients were included, with an average age of 41.7 years. Thirty-six of the patients had seizures from the left hemisphere and 29 from the right. All patients showed an abrupt change in motor activity and resumed contact with the environment as a sign of clinical seizure end- ing. Specific ending signs (nose wiping, coughing, sighing, throat clearing, or laughter) were seen in 23 of 47 of temporal lobe seizures and 7 of 20 extra-temporal seizures. -

Clinical Decision Making in Seizures and Status Epilepticus

January 2015 Clinical Decision Making Volume 17, Number 1 Authors In Seizures And Felipe Teran, MD Department of Emergency Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY; Faculty, Emergency Department, Clínica Status Epilepticus Alemana, Santiago, Chile Katrina Harper-Kirksey, MD Abstract Anesthesia Critical Care Fellow, Department of Anesthesia, Stanford Hospital and Clinics, Stanford, CA Andy Jagoda, MD, FACEP Seizures and status epilepticus are frequent neurologic emergen- Professor and Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Icahn cies in the emergency department, accounting for 1% of all emer- School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY; Medical Director, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY gency department visits. The management of this time-sensitive and potentially life-threatening condition is challenging for both Peer Reviewers prehospital providers and emergency clinicians. The approach to J. Stephen Huff, MD Professor of Emergency Medicine and Neurology, University of seizing patients begins with differentiating seizure activity from Virginia, Charlottesville, VA mimics and follows with identifying potential secondary etiolo- Jason McMullan, MD gies, such as alcohol-related seizures. The approach to the patient Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of in status epilepticus and the patient with nonconvulsive status Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH epilepticus constitutes a special clinical challenge. This review CME Objectives summarizes the best available evidence and recommendations Upon completion of this article, you should be able to: regarding diagnosis and resuscitation of the seizing patient in the 1. Describe the diagnostic approach to patients who have recovered from a seizure and patients in status epilepticus. emergency setting. 2. Recognize and treat patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures.