Clinical Decision Making in Seizures and Status Epilepticus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment

NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. NEUROLOGY – LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS SERIES Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-862-7 (Hardcover Book) Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60876-549-2 (Online Book) Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation Nodar P. Mitagvaria and Haim (James) I. Bicher 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60692-163-0 Cerebral Ischemia in Young Adults: Pathogenic and Clinical Perspectives Alessandro Pezzini and Alessandro Padovani (Editors) 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-627-2 Dizziness: Vertigo, Disequilibrium and Lightheadedness Agnes Lindqvist and Gjord Nyman (Editors) 2009: ISBN 978-1-60741-847-4 Somatosensory Cortex: Roles, Interventions and Traumas Niels Johnsen and Rolf Agerskov (Editors) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60741-876-4 Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment Melanie L. Landow (Editor) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60876-205-7 NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MELANIE L. -

Status Epilepticus: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, and Outcomes

Arch Dis Child 1998;79:73–77 73 CURRENT TOPIC Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.79.1.73 on 1 July 1998. Downloaded from Status epilepticus: pathophysiology, epidemiology, and outcomes Rod C Scott, Robert A H Surtees, Brian G R Neville Convulsive status epilepticus (CSE) is the most consciousness being regained between the sei- common neurological medical emergency and zures. This gives the impression that status epi- continues to be associated with significant lepticus is always convulsive and is a single morbidity and mortality. Our approach to the entity. There are, however, as many types of epilepsies in childhood has been clarified by the status epilepticus as there are types of seizures, broad separation into benign and malignant and this definition is now probably outdated. syndromes. The factors that suggest a poorer To show that status epilepticus is a complex outcome in terms of seizures, cognition, and disorder, Shorvon has proposed the following behaviour include the presence of multiple sei- definition. Status epilepticus is a disorder in zure types, an additional, particularly cognitive which epileptic activity persists for 30 minutes disability, the presence of identifiable cerebral or more, causing a wide spectrum of clinical pathology, a high rate of seizures, an early age symptoms, and with a highly variable patho- of onset, poor response to antiepileptic drugs, physiological, anatomical, and aetiological and the occurrence of CSE.1 basis.2 CSE needs diVerent definitions for Convulsive status epilepticus is not a syn- diVerent purposes. Many seizures that last for drome in the same sense as febrile convulsions, five minutes will continue for at least 20 benign rolandic epilepsy, and infantile poly- minutes, and so treatment is required for most morphic epilepsy. -

Status Epilepticus: Initial Management

DATE: July 2018 TEXAS CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL EVIDENCE-BASED OUTCOMES CENTER Initial Management of Status Epilepticus Evidence-Based Guideline Definition: Status Epilepticus (SE) is a disease process Diagnostic Evaluation resulting in prolonged seizures of longer than 5 minutes. (1) The NOTE: Central nervous system (CNS) infection should be cause of SE can stem from the malfunction of the response to excluded. terminate a seizure or from the commencement of the mechanisms that result in prolonged seizures. (2) If SE History: Assess for continues for longer than 30 minutes, there can be permanent Seizure onset neurological damage, including neuronal death, neuronal Known seizure disorder injury, and alteration of neuronal networks. (2,3) Ingestion Fever (e.g., signs of serious infection) Epidemiology: Convulsive status epilepticus (CSE) is the Medications (4) most common neurological emergency seen in childhood. It o Received prior to presentation (e.g., type, dose, is also among the top five reasons for admission to the PICU at dosage, route) Texas Children’s Hospital and is the third most common o Current anticonvulsant medications reason for transport calls. SE is a medical emergency and is o Use of psychopharmacologic medications associated with an overall mortality rate of 8% in children and Toxic/Subtherapeutic anticonvulsant levels (4,5) o 30% in adults. Among children, the overall incidence of SE Nonadherence and/or recent change (4-6) o is approximately 1 to 6 per 10,000/year. The incidence Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) appears to be higher in children under 1 year of age with over Metabolic abnormalities 50% of cases occurring in children under 3 years. -

Is It a Convulsion Or Dopamine Deficiency? a Case of Epilepsy in Dihydropteridine Reductase Deficiency

Letter to the editor pISSN 2635-909X • eISSN 2635-9103 Ann Child Neurol 2020;28(2):72-74 https://doi.org/10.26815/acn.2019.00304 Is It a Convulsion or Dopamine Deficiency? A Case of Epilepsy in Dihydropteridine Reductase Deficiency Jisu Ryoo, MD, Eun Sook Suh, MD, Jeongho Lee, MD Department of Pediatrics, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Received: December 20, 2019 Dihydropteridine reductase (DHPR) deficiency A 15-year-old man was admitted to Soon- Revised: February 13, 2020 Accepted: March 2, 2020 is a severe form of hyperphenylalaninemia due chunhyang University Seoul Hospital. At the age to impaired renewal of a substance known as tet- of 3 months, he experienced the first seizure, Corresponding author: rahydrobiopterin (BH4), caused by mutations in characterized by brief psychomotor arrest and Jeongho Lee, MD the quinoid dihydropteridine reductase (QDPR) right hand tremor. He had no family history of Department of Pediatrics, gene [1]. If little or no BH4 is available to facili- seizures or genetic disorders. Brain magnetic res- Soonchunhyang University Seoul tate processing phenylalanine (Phe), this amino onance imaging (MRI) and EEG showed nor- Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, 59 acid can accumulate in the blood and other tis- mal results. The seizures were not controlled by Daesagwan- ro, Yongsan-gu, Seoul sues, and the levels of neurotransmitters (dopa- antiepileptic drugs, including topiramate, val- 04401, Korea mine, serotonin) and the folate in cerebrospinal proate, and lamotrigine; therefore, he discontin- Tel: +82-2-709-9341 fluid also decrease [1]. Symptoms such as mental ued the medication. -

The Migraine-Epilepsy Syndrome

medigraphic Artemisaen línea Arch Neurocien (Mex) Vol 11, No. 4: 282-287, 2006 The Migraine- Epilepsy Syndrome Arch Neurocien (Mex) Vol. 11, No. 4: 282-287, 2006 Artículo de revisión ©INNN, 2006 de caso The migraine-epilepsy syndrome Enrique Otero Siliceo†, Fernando Zermeño EL SINDROME MIGRAÑA-EPILEPSIA represent a neural exitation. Since that the glutamate has in important rol in both patologys depending of the part of the brain more affected the symptoms might RESUMEN vary from visual to abdominal phemomena. La migraña y la epilepsia tienen varios puntos en común Key words: migraine epilepsy, EEG abnormalities, sintomática clínica y genéticamente lo que ha sido glutamate, diagnosis. postulado por más de cien años. El fenómeno referido como migraña-epilepsia sugiere que exista una he first steps of a practical, approach by patofisiología común. El síndrome de migraña o physicians in recognizing and treating neuro- epilepsia tiene fenómenos comunes de dolor adominal T logic diseases are to recognithat there are jaqueca anormalidades del EE y respuesta a droga various overlaps between migraine and epilepsy. antiepilépticas. En ocasiones el paciente puede tener Epileptic seizures and classic migraine episodes may un ataque migrañoso o una convulsión o en otras occur in the same patient. Migraine and epilepsy share ambas. La comorbilidad puede explicarse por estados several genetic, clinical, evolutive and neurophysio- de hiperrexcitabilidad neural. Alteraciones electroen- logic features. A relationship between epilepsy and cefalográficas son comunes en estos estados. En migraine has been postulated for over a hundred years apariencia el glutamato tiene un papel importante tanto and the syndrome of Migraine-Epilepsy illustrates this en la migraña como en la epilepsia. -

Migraine Triggered Seizures and Epilepsy Triggered Headache and Migraine Attacks: a Need for Re-Assessment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central J Headache Pain (2011) 12:287–288 DOI 10.1007/s10194-011-0344-2 COMMENTARY Migraine triggered seizures and epilepsy triggered headache and migraine attacks: a need for re-assessment Paul T. G. Davies • C. P. Panayiotopoulos Received: 5 April 2011 / Accepted: 8 April 2011 / Published online: 24 April 2011 Ó The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com In this issue of the Journal, Belcastro and associates review Migralepsy terminology and classification issues for migralepsy, hem- icrania epileptica, post-ictal and ictal headache [1]. They According to the ICHD-II 1.5.5, ‘‘migraine-triggered sei- raise key points such as ictal headache and visual seizures zure (sometimes referred to as migralepsy)’’ denotes an are often misdiagnosed as migraine, ‘‘migralepsy’’ is unli- epileptic seizure that occurs ‘‘during or within one hour kely to exist and an ‘‘epilepsy-migraine sequence’’ is much after a migraine aura’’ [3]. However, the evidence of this more common and well documented than the dominant ‘‘migraine-seizure’’ sequence is weak and the proposed view of a ‘‘migraine-epilepsy sequence’’. Their relevant criterion of 1 h gap between the end of the ‘‘aura’’ and the proposals need appropriate attention by the committee of start of an epileptic seizure is entirely arbitrary the international classification of headache disorders Migralepsy is an old term derived from migra(ine) and (ICHD) as well as the physicians in their clinical practice (epi)lepsy, coined by Dr Douglas Davidson, but mainly because of the consequences that misdiagnosis may have on attributed to Lennox and Lennox, which we quote, ‘‘a patients. -

A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy And

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Neurological Medicine Volume 2013, Article ID 460701, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/460701 Case Report A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and Multicentric Castleman’s Disease Mohankumar Kurukumbi,1 Sheldon Steiner,1,2 Shariff Dunlap,1 Sherita Chapman,3 Noha Solieman,1 and Annapurni Jayam-Trouth1 1 Department of Neurology, Howard University Hospital, 2041 Georgia Avenue, Washington, DC 20060, USA 2 Department of Neurology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC 20060, USA 3 Department of Neurology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Mohankumar Kurukumbi; [email protected] Received 27 June 2013; Accepted 17 July 2013 AcademicEditors:T.K.Banerjee,J.L.Gonzalez-Guti´ errez,´ R. Hashimoto, J. C. Kattah, and Y. Wakabayashi Copyright © 2013 Mohankumar Kurukumbi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) development in HIV with preexistent progressive multifocal leukoen- cephalopathy (PML) has been extensively studied. PML-IRIS typically manifests clinically as new or worsening neurologic symptoms in conjunction with enlarging CNS lesions and occurs in approximately 10–20 percent of HIV-infected patients with PML who begin HAART. Likewise, Multicentric Castleman’s Disease (MCD), a rare malignant lymphoproliferative disorder, has a strong and well-known association with HIV. Our case provides a rare instance of PML-IRIS in combination with MCD in an HIV-positive individual. -

Myoclonic Status Epilepticus in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Original article Epileptic Disord 2009; 11 (4): 309-14 Myoclonic status epilepticus in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy Julia Larch, Iris Unterberger, Gerhard Bauer, Johannes Reichsoellner, Giorgi Kuchukhidze, Eugen Trinka Department of Neurology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria Received April 9, 2009; Accepted November 18, 2009 ABSTRACT – Background. Myoclonic status epilepticus (MSE) is rarely found in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and its clinical features are not well described. We aimed to analyze MSE incidence, precipitating factors and clini- cal course by studying patients with JME from a large outpatient epilepsy clinic. Methods. We retrospectively screened all patients with JME treated at the Department of Neurology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria between 1970 and 2007 for a history of MSE. We analyzed age, sex, age at seizure onset, seizure types, EEG, MRI/CT findings and response to antiepileptic drugs. Results. Seven patients (five women, two men; median age at time of MSE 31 years; range 17-73) with MSE out of a total of 247 patients with JME were identi- fied. The median follow-up time was seven years (range 0-35), the incidence was 3.2/1,000 patient years. Median duration of epilepsy before MSE was 26 years (range 10-58). We identified three subtypes: 1) MSE with myoclonic seizures only in two patients, 2) MSE with generalized tonic clonic seizures in three, and 3) generalized tonic clonic seizures with myoclonic absence status in two patients. All patients responded promptly to benzodiazepines. One patient had repeated episodes of MSE. Precipitating events were identified in all but one patient. Drug withdrawal was identified in four patients, one of whom had additional sleep deprivation and alcohol intake. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

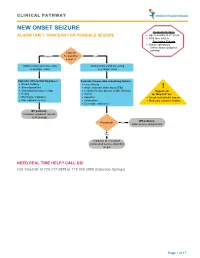

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Emergency Department Management of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. -, No. -, pp. 1–4, 2016 Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.10.042 Selected Topics: Psychiatric Emergencies PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES FOR CLINICIANS: EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT MANAGEMENT OF NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME Michael P. Wilson, MD, PHD,*† Gary M. Vilke, MD,*† Stephen R. Hayden, MD,* and Kimberly Nordstrom, MD, JD‡§ *University of California at San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, California, †Department of Emergency Medicine Behavioral Emergencies Research (DEMBER) Laboratory, University of California San Diego, San Diego, California, ‡Denver Health Medical Center, Department of Behavioral Health, Psychiatric Emergency Service, Denver, Colorado, and §University of Colorado Denver, School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado Reprint Address: Michael P. Wilson, MD, PHD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at San Diego Medical Center, 200 West Arbor Drive, Mail Code #8676, San Diego, CA, 92103 , Keywords—altered mental status; neuroleptic malig- What Do You Think is Going on with This Patient? nant syndrome; dystonia; catatonia; rigidity The clinical presentation suggests neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). Although first described more than 50 years ago, the diagnosis of NMS is primarily CLINICAL SCENARIO clinical (1). A 25-year-old man presents with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia. He was discharged 1 week earlier from What Key Findings Lead to the Diagnosis? an inpatient psychiatric unit. His mother states that he has been acting ‘‘differently’’ for the past 2 days. He Clues to an NMS diagnosis include a recent diagnosis of a has not been ‘‘making any sense,’’ has felt warm to the psychotic disorder and inpatient psychiatric hospitaliza- touch, and today has been stiff and moving rigidly like tion.